Go here for enlightenment.

Category Archives: Eggs

Egg-Based Pudding Discussions

It is a rule of thumb that in any egg-based pudding discussion, at some point the phrase “over-egging the pudding” will be deployed, whether or not it is pertinent.

It is entirely conceivable that you have absolutely no idea what I am talking about, so to clarify matters for the dull-witted I shall give an example of a snatch of dialogue from a fairly routine egg-based pudding discussion. This is not something I have made up, woven out of whole cloth from the fuming phantasms of my inner head, but a genuine extract from an egg-based pudding discussion I tape-recorded especially that I might transcribe it for an eventuality such as the present one. I hope all this is crystal clear.

Snippy – I must say for as long as I can remember I have been fond of egg-based puddings.

Cleothgard – Some might say “overfond”, ha ha ha.

Snippy – No, I don’t think I could be accused of being overfond of egg-based puddings. It is not as if I am forever guzzling them. Perhaps once or twice a month I might treat myself to an egg-based pudding, which seems a reasonably moderate rate to me.

Cleothgard – Now you are adopting a very defensive posture.

Snippy – I am not. I am merely saying that by calling me overfond of egg-based puddings you were, let us say, ha ha, over-egging the pudding yourself.

That should make clear to you the point I was making, which – to repeat – is that the phrase “over-egging the pudding” will make an appearance, usually fairly early on, in any egg-based pudding discussion. I hasten to add that the extract from the conversation between Snippy and Cleothgard is absolutely genuine, a transcription of a tape-recorded egg-based pudding discussion held at the edge of a field, next to a filbert-hedge, on a somewhat damp Thursday afternoon in the latter years of the last century. The exchange was recorded on a cassette tape and that cassette tape has been kept, securely, in the locked drawer of a desk, the desk being in the private cabin of a trusted sea-captain, trusted by me, at any rate. This sea-captain is captain of a ship which has been roving the high seas almost continuously since the cassette tape was entrusted to the captain and he locked it in the drawer of the desk in his private cabin. Interestingly, the captain’s name is Captain Pudding and his head resembles an egg.

If you have been affected by this discussion of over-egging the pudding, please call our helpline.

Me And My Eggs

I keep all my eggs in one basket. I have several baskets, obtained during what I like to think of as my “basket-acquiring years”, but there is only one in which I put my eggs. This is a small, oval, wicker basket, a bit tatty with age, which I keep on one side of the countertop in my kitchen. My other baskets I use for a number of different purposes, in different parts of the house, and outside. One purpose to which they are never, ever put is for the keeping of eggs. The eggs always go in their designated basket.

I usually buy half a dozen eggs at one time. Invariably, they come packaged in a cardboard egg-carton specifically designed for the storage of eggs. Some people are happy to leave the eggs in the carton once they get them home. That is their choice and it is not one with which I would argue, unless I was in a frantic and fractious frame of mind and, at the end of my tether, looking for a pretext to blow my top and indulge in a violent argument. Shouting my head off about the pros and cons of different egg storage possibilities can be a splendid way to let off steam. In general, though, I tolerate the practice of leaving the eggs in the carton you bought them in, so long as my own preference for putting my eggs in a basket is accepted in return. It usually is.

It would be a mistake to think that six is the maximum number of eggs in my basket. I make it my habit to buy a new carton of eggs when there is still one egg, or even two, in the basket. Thus the maximum number is seven or eight. When adding the newly-bought half dozen eggs, what I do is to remove, temporarily, the one or two eggs remaining in the basket, put the fresh eggs in, carefully, and then place the one or two older eggs, even more carefully, on top of the clutch. If I did not do this, the same one or two eggs would always remain at the bottom, and might never get used, and they would rot, from the inside, unbeknown to me until such time as I cracked the shell and released an unutterable Lovecraftian stench.

Placing the one or two older eggs atop the clutch is not without risk, of course. When removing them temporarily from the basket, I cannot simply place them on the countertop. If I were to do that, they might, being egg-shaped, roll all the way off the countertop and smash upon the floor. Mopping up egg innards and shattered shell is never a pleasant business. Thus I first lay out a tea-towel on the countertop, and put the older eggs on that, to avert any rolling. It has been suggested that I might temporarily place the older eggs in one of my other baskets. Superficially attractive as that may be, I loathe the very idea. As I insisted at the outset, I like to keep my eggs in one basket.

One great advantage of my system is that I have an empty egg carton to muck about with. Judicious use of scissors and paint and glue can transform the carton into a few hats for gnomes. There are lots of other things you can do with empty egg cartons, of course, but that is the one I always return to. My gnomes are always losing their hats in high winds.

Now. A terrible thing happened last week. I was at a swish cocktail party, leaning insouciantly against a mantelpiece, when I heard, above the hubbub, a snatch of conversation. One of the guests, in a voice as strident as a corncrake’s, said “Well, you know what they say, never keep all your eggs in one basket”. It is hard to describe the effect these words had on me. They came with the force of a thunderclap. I felt unmoored from all that was familiar, all I held dear, all I knew. “They”? Who were “they”, who said this, with such confidence, such authority? Steadying myself against the mantelpiece, I stood on tiptoe, craning my neck to peer over the heads of the partygoers, trying to see who it was who had said these awful, hideous words.

There could be only one culprit. He sounded like a corncrake, and he looked like a corncrake, and now he was saying something about not counting chickens. I clutched at the mantelpiece, fearing I would swoon. No man should be allowed to live who could utter such things. My head throbbing, I felt in my pocket for my stiletto. Damn .. . . it was not there. Panicked, I rummaged in my other pockets, in vain. Then I remembered that I had left my stiletto at home, in one of my other baskets, the big, blood-soaked one, the one in which I keep my stilettos and knives and hatchets and axes and slicers and shivs.

Source : Me And My Eggs, by the lumbering walrus-moustached psychopathic serial killer Babinsky.

Pointy Town Egg Dream

Last night I dreamt I went to Pointy Town again. I went by way of the Blister Lane Bypass, where important roadworks were taking place. In spite of the fact that I have never in my life been within twenty feet of a pneumatic drill, I took it into my head that I wished, with all my heart, to take part in the roadworks. I hopped off my bus – a number 666 – dodged through the many container lorries thundering along the road in both directions, and, anent a muddy trench, grabbed hold of an unattended machine tool. With sure and steady thumb, I depressed the knob that spurred the machine to life, and proceeded to gouge out crumbly slabs of geological significance from the bottom of the trench. This being a dream, I was able to continue my deft roadworks until I reached the burning core at the centre of the earth. I stilled my machine, and dug through the final layers of rock fragments with my bare hands, and there I discovered an egg.

“This is the egg of the world,” I said, “I wonder what will hatch from it?”

With the egg nestled in a pocket of my Tyrolean jacket, I clambered back up to the earth’s surface. Oddly, instead of finding myself at the Blister Lane Bypass, I was in Pointy Town itself, near the viaduct, outside the Old Collapsing Abandoned Swimming Pool. The door was ajar, and I pushed it open without the least trace of fear and stepped inside. As I did so, I heard the egg in my pocket crack.

In the empty pool, with its distorting acoustics, a jug band, as if awaiting my arrival, struck up a jug band arrangement of “Mother Goose” by Jethro Tull. Was it a goose egg I had in my pocket? I fumbled in my pocket to hoist out the cracking egg. Something nipped my fingers, and I quickly pulled out my hand, eggless. Blood was flowing, far more copiously than one would expect from the tiny bite I had received. I waved my hand and my blood splattered the jug band. They played on, undisturbed.

That is the thing about dreams, they make no sense. They have no significance. I am not even sure what a jug band is. I have never engaged in rogue roadworks. I have never been to Pointy Town.

Orwell’s Diary 8.1.39

Three eggs.

Regular readers will be aware that whenever I quote from George Orwell’s diaries I give the full and unabridged entry for the day in question. Tomorrow we will have to move on to a different diarist, so it is only fair that I take the opportunity to draw your attention to further, ornithologically significant, excitements in Orwell’s life which took place on the ninth of January 1939. Not merely

Two eggs

but

Saw large flock of green plover, apparently the same as in England.

Did he think foreign plovers would somehow differ from clean, decent, English plovers?

On Breakfast

Dear Mr Key, writes Poppy Nisbet, I like to think I am the world’s leading authority on Hooting Yard. I spend at least four hours a day reading and rereading – and rerereading! – your work, and try to fit in a further two hours listening, or relistening, (or rerelistening!) to a few of the hundreds of podcasts available from Resonance104.4FM. A couple of years ago I made the wise decision not to bother ever reading anybody else, and tossed on to a bonfire various books I had accumulated, including all my signed first editions of Jeanette Winterson. I have never regretted that decision, and indeed I took several snapshots of the flames consuming the La Winterson tomes, and made a tape recording of the crackling blaze. These are intended as mementoes for my grandchildren, to teach them a valuable lesson about life and literature.

I will shortly be appearing on the television quiz show Socially Inept Brainbox Challenge, where of course I shall be taking Hooting Yard as my special subject. I have every confidence that I will achieve the top score of 92 out of 92, but to be on the safe side I am poring over your works with even greater diligence and concentration than ever, making many notes in my jotter pad. Incidentally, this jotter pad I will also be bequeathing to my grandchildren. They do not know how lucky they are.

All this is by way of preamble to explain my consternation upon reading your piece yesterday on cornflakes. For round six of Socially Inept Brainbox Challenge I have chosen as my intensive grilling topic Breakfast At Hooting Yard. I am all too aware that breakfast is almost the only meal of the day ever mentioned in your work. Nobody seems to have luncheon or dinner or supper, at least not with any regularity. But you harp on about breakfast all the time, and a quick search elicits over one hundred separate pieces in which it is mentioned in greater or lesser detail. The thing is, these multitudinous breakfasts are almost always eggy, and when they are not they often involve smokers’ poptarts or some sort of fish-based preparation. While we read occasionally of breakfast cereal cartons, said cartons have usually been torn up and the cardboard used for scribbling upon, or for the construction of toy squirrels, etcetera. We rarely find anyone actually eating breakfast cereal, and when they do it is as likely as not Special K.

I was therefore not merely in a state of consternation but actively flabbergasted to read a piece in which cornflakes were an all-consuming passion. It seems to me that this is without precedent in your work. Now, we can take this in a number of ways. It may signal a bold new direction, and a not unwelcome one. Those of us whose lives beat to a Hooting Yard pulse are always ready to learn a new rhythm. At least, I think so, though I suppose I can only speak for myself. Conversely it may be that a sudden shift from eggy breakfasts to cornflakes leaves certain readers feeling unmoored, bewildered by a tangle of unfamiliar signposts. I admit this was my own initial response. I found myself having to reread all your breakfast-related babblings to tally up the eggs and smokers’ poptarts and kippers and so on, wondering if I had lost my wits. It certainly put me off my stride in terms of my prep for Socially Inept Brainbox Challenge, so bear in mind that if my score is less than the highest possible 92 I am going to hold you personally responsible, Mr Key.

What I need to know, before the charabanc arrives to take me to the television studios for the recording of the quiz, is whether the cornflakes mania to which you devoted yesterday’s piece is an anomaly, or whether we ought to prepare ourselves for further breakfast unhingements. Or are we to find that cornflakes are now on the standard Hooting Yard breakfast menu? If the latter, I think you owe it to your readers to make a compelling case for cornflakes over Special K, an alternative cereal which, I would aver, fits more snugly into the glorious and only semi-fictional world of Hooting Yard.

I await your considered response with bated breath. Not that I am aware quite how I might bate my breath. I am gravely disappointed that nowhere in the entire Hooting Yard canon can I find any guidance on the matter. As I never read anything else, I suppose I must remain in a state of dire ignorance (and unbated breath) until such time as you choose to address the topic. And while you are about it, you might also turn your attention to giraffes, of which you have had very little to say, and that little not particularly enlightening.

I remain, yours etc.

Poppy Nisbet

By way of reply, I would direct Ms Nisbet to World Wide Words, which gives as concise and informative an explanation of bated breath as one could wish for. As for cornflakes, I don’t know what to say. Yesterday I was merely reporting what I had heard on the grapevine about Pepinstow. I may have misheard, or it might have been garbled, and it may well be that Pepinstow’s mania was indeed for Special K rather than cornflakes. But in order to find out, I would have to track down my informant, and that would be no easy matter. Pepinstow’s tale was told to me by a very elderly gent I met down at the quayside. He was, by his own description, an ancient mariner, and I noted that he had an albatross – not, sadly, a giraffe – slung around his neck, like a necklace. He jabbered the Pepinstow business at me before embarking on a boat, bound for distant shores the whereabouts of which I know not. That is the thing with albatross-disporting ancient mariners, in my experience you cannot always rely on them, more’s the pity.

Orwell’s Nightmare

On Eggheads

Alfred Hitchcock was terrified of eggs. In 1963, he said: “I’m frightened of eggs, worse than frightened, they revolt me. That white round thing without any holes… have you ever seen anything more revolting than an egg yolk breaking and spilling its yellow liquid? Blood is jolly, red. But egg yolk is yellow, revolting. I’ve never tasted it.” This is what we can call a “foolish fear”. After all, why should a rich and successful film director be scared of an egg?

There is nothing foolish, however, about a fear of eggheads. I do not mean “eggheads” in the conventional sense, to denote extremely brainy persons and boffins. To be terrified of that sort of egghead would be as foolish as to be afraid of eggs. It is true that one might be frightened of a demented and power-crazed egghead about to press the knob on the Doomsday machine, but that is a rare event, and in general one is more likely to be scared by rampaging thicko barbarians than by eggheads.

The egghead it is not foolish to fear is the literal egghead. I mean, it is hard to imagine something genuinely more terrifying than a human body with an egg where its head ought to be. Picture it – a man or a woman, of average height, average build, averagely dressed, but with a neck tapering to a sort of eggcup formation, atop which rests an egg. Not some kind of giant human head-sized egg, but a common chicken egg, of the kind one buys by the half dozen in a carton. I don’t know about you, but if I was sashaying along the boulevard of an important city and came face to face with such an egghead, I would run away screaming.

We are used to heads that have eyes and a nose and a mouth and ears. However arrayed, fortuitously or in a somewhat lopsided manner, these are the features we associate with what we understand as a head. Human heads deformed by horrible accidents or mishaps at birth will still largely conform to a generic headness, as do, in their own ways, the heads of beasts and birds. Some insect heads, under a microscope, can appear alien and mildly alarming, but they retain a set of recognisable features with which we can become familiar and accommodate ourselves, particularly when we are reminded that they are grossly magnified and really quite tiny.

It is the awful blankness of the egghead that is so unnerving and ruinous to our sanity. That smooth, fragile shell, white or brown or sparsely speckled, admits of no features whatsoever. We cannot, Mr Potatohead-like, poke eyes and a nose and ears and a mouth in to it, for in so doing we would only crack the shell. And not only is it an awful blank, but its size is out of proportion to the body atop which it rests, somehow making it all the more frightening.

We must consider, too, that its smooth and featureless form robs it of senses. Without eyes, it cannot see. Without a nose, it cannot smell. Without ears, it cannot hear. Without a mouth, it cannot speak. Even if we allow that within the eerie shell there may lurk a brain, that brain would be tiny in comparison to the human brain, and, devoid of sensory stimulation, an unimaginable horror. In short, the egghead would be akin to a zombie. It is truly the stuff of nightmares.

I count myself fortunate that I have never actually had a nightmare about eggheads. I hope I never will. But it strikes me that they could well prompt nightmares in others were they to be deployed in a blockbuster horror film. Attack Of The Eggheads From Outer Space has a pleasingly 1950s ring to it. One imagines the spaceship landing conveniently close to a major American city, and the eggheads rampaging through the streets trailing chaos in their wake. Though it is unclear how a zombie-being with an egg for a head might cause harm, other then by creating terror in those who see it lumbering towards them on an otherwise uneventful sunny day.

One could, alternatively, devise a film from the perhaps even more terrible perspective of the egghead itself. Our hero goes to bed one night and wakes up in the morning with an egg where his head used to be. This would be a suitable premise, not for a horror film, but for a piece of mawkish pap starring, inevitably, Robin Williams. Only he, I think, has the chops to make an audience weep at the plight of an egghead. Indeed, he has the talent – if one can call it that – to make believable a scene where the egghead itself weeps. But would its tears be yellow?

This brings us back to Hitchcock. Had he not been such a scaredy cat about eggs, he would surely have made the definitive egghead film, Eggheado, perhaps, or Eggheads By Eggheads West or To Catch An Egghead or The Thirty-Nine Eggheads or Dial E For Egghead or The Man Who Knew Too Many Eggheads or Eggheads On A Train or The Wrong Egghead or Eggheadbound or The Egghead Vanishes or Shadow Of An Egghead or even just The Eggheads. Hitchcock being Hitchcock, there would no doubt have been a scene where Tippi Hedren gets splattered with egg yolk. Or would it be revealed that her blonde hair is neither blonde nor hair, but an eruption of thin strings of egg yolk from what, in a heart-thumpingly suspenseful scene, we discover is not Tippi’s human head at all, but… an egghead!

On Bravura Bunkum

The speech, it was agreed, was bunkum, but it was bravura bunkum. Certainly, to judge by the prolonged clapping of hands at the finish, accompanied by faintly hysterical screeches, it had gone down a storm. I wrote in my diary at the time that it was my first, and possibly last, experience of bravura bunkum.

‘Bunkum’ is also spelled ‘buncombe’. You can take your pick. The Japanese have a word for it, but I do not know what it is. Perhaps they call it bunkum too. I could find out, if I were avid to know, but I am not. Why should I waste my precious hours on this tingling planet wondering what word they use to describe bunkum in faraway Japan? I have better things to do. I made a list of them, in my diary, years ago, and am gradually working my way through it. It is good to have a plan.

Mother looked over my list, shortly after I had compiled it, and crossed out a number of items, savagely, with her pencil. She wore a blue brooch on her bosom and her hair was tangled and as dry as straw. She peered at my list through her lorgnette, lips pursed, emitting the odd snort, and now and then something would cause her grief and she would stab the pencil on the page and slash it back and forth across the words I had written. I cannot for the life of me remember why I let her read my diary in the first place, quite apart from then allowing her to obliterate certain of the plans I had made for my life. It was surely not filial devotion. She was a mad old bat with a fragile grasp on reality. In any case, I could have ignored her scratchings, rewritten my list in a separate notebook with the deleted items reinstated, but I did not. Nor did I ever ask Mother what prompted her disapproval, not that I would have been likely to understand her reply, for her babblings were for the most part incoherent. There were moments of lucidity, usually after she had eaten an egg, but at such times she used the opportunity to give commands to the servants.

So many years have passed that I barely recall the items on my list which Mother scratched out, and so effective was the savagery of the scratchings that they are pretty much illegible. For whatever reason, I never did pursue those plans. One, that can still be read, was a desire to “Collect even more ants than Horace Donisthorpe”. In retrospect, I am rather glad Mother crossed that one out. Donisthorpe devoted six decades to the collection of ants. Six decades! I am not that interested in ants, and I would hardly have had time to do anything else. I might never have fulfilled one of my other plans, which was to “Listen to a lot of bunkum”.

Now that one I did pursue, and I pursued it systematically and with great vigour. If I heard rumours abroad of the speaking of bunkum, I made sure I was on the spot when the time came for it to be spouted. I never made any notes, I had no desire to remember any of the bunkum after the speaker was done. I just wanted to listen. And listen I did, here and there, over the course of many years. It was not beyond my wit nor my means to go to Japan, to hear Japanese bunkum, or whatever they call bunkum in Japan, spoken, but I never did. I am sure Mother would not have stood in my way, had I brandished a ticket for an ocean voyage and a Japanese phrasebook, waved them in front of her, and announced that I was setting out at the break of dawn. Had she recently ingested an egg, she might have questioned me about the purpose of my trip and its likely duration, but she would not have stopped me going. I did not go because, I confess, I was frightened of Japan, of faraway Japan.

No doubt it was an irrational fear. I was not, for example, in the least afraid of huge swathes of the globe, from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli. I felt almost affectionate towards eastern Europe, and often had pleasant dreams of Africa. Not that I ever visited these parts, but I would happily have done so had I ever been granted a passport. Sadly, I was not allowed one, by dint of some past infraction committed by Mother in the ambassador’s official residence in a geopolitical hotspot. I never did find out exactly what she had done, or not done, and never asked, in a lucid post-egg moment, when I might have found out. I think there is part of me that did not wish to know.

But I certainly never needed to go to Japan, or to anywhere else, to hear bunkum. There was a vast amount of it to be heard close to home, within the distance of a short bus ride. Perhaps there is as much bunkum elsewhere in the world, or it may be that there is something particular about my little bailiwick that attracts bunkumites – a word defined by the OED as “one who talks bunkum”. Whatever the case, I heard more than enough bunkum over the years, without ever having encountered bravura bunkum.

That was what made Thursday afternoon, in that marquee, on that lawn, in that park, so decisive in my life. Having heard bravura bunkum, I had to ask myself if I wished or needed to hear any other bunkum ever again. I asked myself because I could not ask Mother, who by this time was cold in her grave, in the cemetery adjoining the very same park, her grave set upon a little hillock, where stood a sycamore on the branches of which birds perched, ravens and crows. When Mother first lay there, before the worms got her, I would sometimes go to the hillock and ask questions of the birds. The birds always answered me, cawing, cawing, but I could never interpret the caws nor wring any sense from them. Eventually I ceased to make those visits, and learned to trust to my instincts.

It was instinct that made me take from the sideboard drawer Mother’s pencil, and to cross out the item in my list of plans to “Listen to a lot of bunkum”. I scratched through it savagely, as Mother might have done, but I was calm, eerily calm, as I did so. Now I need never hear any bunkum again. I can move on, at last, to the next item on my list of things to do during my lifetime. I closed the diary, returned Mother’s pencil to the sideboard drawer, and shuffled into the kitchen to boil an egg.

On Soviet Hen Coops

Soviet Hen Coops is the latest bestseller by blockbuster paperbackist Pebblehead, a sweeping and magisterial cross-cultural history of poultry under Communism. On the face of it, this seems an unlikely subject for a book which has been flying off the shelves of airport bookstalls and has, in the past week alone, earned Pebblehead more money in royalties than J K Rowling has had hot dinners. But then, in the hands of the potboilerist, the most unpromising material is handled with such mastery and aplomb that, in places, it reads like the most nerve-wrenching and nail-biting and heart attack-inducing of thrillers.

So I am told, in any case, as I have not yet read it myself. A while ago, I set myself the task of reading the entire Pebblehead canon, to date, in chronological order, and I do not wish to cheat. Thus far I have reached the autumn of 1972 (Swarthy Fiends In Dungeons Grim) and have a couple of hundred titles to get through before I catch up with the latest tome. Thus I have relied on a specially-empanelled panel of readers to report to me their responses to Soviet Hen Coops. In choosing the panel, I was careful to exclude those with expert knowledge either of Soviet Communism or of hens, for Pebblehead is nothing if not a populist, and it is the general reader, and indeed the barely literate halfwit, for whom the bulk of his output is intended.

Initial reactions were overwhelmingly positive, with the panel giving the book an overall rating of “Fantastic!”. Converted into numerals, this worked out as 10 out of 10, though a couple of panel members were keen to go up to 11. As a sample of a detailed critique, I have plucked this from the pile of written reports:

Having never read a Pebblehead book before, or indeed any books at all, I was absolutely riveted to my armchair. Knowing nothing of Russia and its satellite states in the years between 1917 and 1992, the whole Communism thing was new to me, as was the stuff about poultry, for I have never been near a hen coop in my life, suffering as I do from an allergy to bird feathers. At times it was like reading an adventure story, or as I imagine it might be to read an adventure story. I had to grip the arms of my armchair and cling on by my fingertips, because I got so excited I thought I might topple out of it and fall on the floor. And because I was holding on so tight to the armchair I could not at the same time hold the book, so I had to have a sort of makeshift lectern erected in front of me, to rest the book upon, and I had to employ an unpaid intern from a nearby orphanage to turn the pages for me. And turn the pages they did, for this book is a real page turner! If I have one criticism, it is that Pebblehead does not tell us anything whatsoever about the state of hens and hen coops in the immediate pre-Soviet era, so we cannot place the state and circumstances and milieu of the Communist hen in any context.

I should interrupt the critique here to let slip some inside knowledge. I have it on good authority that Pebblehead is currently hard at work, in his so-called chalet o’ prose, on a prequel tentatively entitled Tsarist Hen Coops. Clearly, he did not wish to duplicate his material.

One chapter I found particularly thrilling was that which deals, in spellbinding detail, with the sudden and complete transformation of Cheka hen coops into OGPU hen coops on the sixth of February 1922. The footnote which lists other notable events to happen on the sixth of February, including, in 1958, the Munich Air Disaster, is the best footnote I have ever read. It is true I have only read half a dozen footnotes in toto, the ones in this book, but of those six this one is by far the best.

Another passage which had me gulping for air and requiring urgent medical attention was the part about the creation of Potemkin hen coops designed to pull the wool over the eyes of useful poultry idiots, the hen equivalents of Sidney and Beatrice Webb. Reports went back to West European and American hens about the idyllic lives of their Soviet sisters, leading to unrest and kerfuffle in a number of farmyards. I would have liked to learn more about Soviet eggs, but

I am going to interrupt here again, to point out that Pebblehead’s next scheduled blockbuster, when he has finished writing Tsarist Hen Coops, will almost certainly be a fat doorstopper entitled Eggs In The Soviet Union.

Actually, I think we have had quite enough of that readers’ report. I think it is clear from her enthusiasm that yet again Pebblehead has pulled out all the stops and produced a rollicking rollercoaster of a narrative. I just wish I knew how he does it. Day in, day out, he sits there in his Alpine fastness, pipe clenched between his jaws, pounding the keys of that battered Fabiocapello typewriter, which long ago, in 1977, lost its J and K keys and as a result forced on him a complete rethink of his prose style.

Please note that Soviet Hen Coops is entirely devoted to hen coops in the Soviet Union, and nowhere concerns itself with the card game Soviet Hen Coop. My spies tell me that Pebblehead will turn his attention to this exciting pastime once he has bashed out Tsarist Hen Coops and Eggs In The Soviet Union and one or two other books he has in the pipeline. It will certainly be a title to look forward to, not least because Pebblehead himself has been called the king of Soviet Hen Coop players, regularly winning tournaments and having his name engraved over and over and over again on several golden and pewter trophies which he keeps lined up on the mantelpiece in his chalet o’ prose, and dusts with a rag on the rare occasions he can tear himself away from his typewriter.

On Sand Robots

The creation of the first fully operational sand robot is a tale of maverick science and unparalleled seaside resort ingenuity. For it was a maverick scientist, on holiday at a seaside resort, who conceived the idea of the sand robot, and built one, and made it work. As always with stupendous scientific initiatives, there were many false starts and hiccoughs along the way. From the first glimmer of the idea within the maverick brainpans of Ignatz Edballs to the initial wheezing plodding creaking steps of the prototype sand robot, entire days passed in witless tinkering and frustration and, sometimes, yes, despair. But in spite of all he never gave up, and at last, a fortnight after the spark of inspiration, the world’s first sand robot took its first steps across the glistening sands of Dilapidation-On-Sea.

There was little in Ignatz Edballs’s past – nor, indeed, his present – which would have prepared the world for his matchless achievement. Those holidaymakers whose jaws dropped open as they watched the sand robot bearing down on them upon the beach could never have guessed that its creator was a lowly janitor at a mop factory. Nor would they realise that it was only by accident that he had come to the seaside resort in the first place. Given two weeks’ furlough by his overseer, Edballs packed a suitcase and headed for the railway station, intending to go to somewhere with mountains and snow and goats, for he was temperamentally attuned to mountains and snow and goats. As it happened, he was fatefully distracted by the hoot of an owl in the rafters of the railway station, and boarded the wrong train. Thus it was he found himself in Dilapidation-On-Sea. There were no mountains, no snow, and no goats. He was inappropriately dressed, and he was terrified of the sea. And so, having booked a room in an insalubrious guest house and sat on the hard bed and sobbed, he summoned from within the deepest core of his being a reserve of manly grit, and headed down to the beach, and lay upon the sand, and smoked his pipe.

In all the years he had been mopping the corridors of the mop factory, Ignatz Edballs had been turning over in his mind various ideas for creating an automaton. This was, let us remind ourselves, the nineteen-fifties, and automata were, for most people, the stuff of science fiction. Edballs was not an aficionado of the genre, but his visions of the robot he would build fell in with the conventions of the time. It would be of humanoid shape, and chunky, and it would whirr and clank and plod, and possibly have some flashing lights and buzzers. In other words, it would only vaguely resemble the sand robot he actually made.

He sat on the beach, smoking his pipe, his back turned to the terrifying sea, and he picked up handfuls of sand and let it fall through his fingers. As an amateur scientist, he knew that sand could be turned into glass, however unlikely that seemed to the dimwitted brain. And it was as he considered the unlikelihood that this stuff falling through his fingers could be turned into something solid and flat and see-through that he wondered if it could also be turned into something of humanoid shape that whirred and clanked and plodded, and could even be imbued with primitive intelligence. And so the spark was lit.

The history of scientific achievement is littered with happy accidents. We have already seen how Ignatz Edballs was only sitting surrounded by sand because of the hoot of an owl. It would be splendid to be able to say that it was another hoot, of a second owl, that set in train the creation of the world’s first sand robot. But it was not. Rather, it was the shrieking of gulls. It was this ungodly din that made Edballs look round, towards the sea he feared so, and to note, as he had never noted before, that sand, when wet, becomes impacted, and, while wet, solid. His keen scientific brain instantly realised that, if an adhesive agent were added to the sand while it was wet, it could remain solid when it dried. Leaping up from the beach, he scampered into the streets of Dilapidation-On-Sea in search of such an adhesive. And here there was a second happy accident. In his excitement, running pell mell, Ignatz Edballs collided with a seaside resort hawker, an egg-man selling eggs laid by his Vanbrugh chicken. One egg fell to the ground, and smashed upon the paving, and Edballs stepped into the egg’s spilled innards. He paid the hawker for the breakage, then sat on a seaside resort bench to wipe the egg-goo from the sole of his boot. And then he saw, in a flash, that it was sufficiently viscous to act as an adhesive, the adhesive that could bind wet sand, the wet sand which he could mould into the frame of a robot!

The rest is history. Ignatz Edballs chased after the hawker and bought all his remaining Vanbrugh chicken eggs. Then he returned to the beach. Fearful of approaching too close to the awful sea, he commandeered the services of a sandcastle-building tot to fetch pail after pail of wet impacted sand from the shoreline. Slowly, over the following fortnight, he moulded the sand, fortified with albumen, into a humanoid shape, nine feet tall. When it was done, he inserted various bits of wiring and magnets and resonators, and fashioned a control panel small enough to be worn on the wrist, similar to the one sported by General Jumbo to control his army of miniature soldiers and sailors and airmen in the comic strip you will recall from days gone by.

We must be thankful that Ignatz Edballs never managed to build an army of sand robots. His prototype proved to be an automaton of awesome destructive power. Within seconds of stirring into artificial life, as it plodded across the bright sands of the beach at Dilapidation-On-Sea, the strange sandy synapses in its strange sandy artificial brain snapped into artificial yet malevolent life, and it went on the rampage. It was a slow, plodding rampage, but a rampage nevertheless, as hordes of screaming terrified holidaymakers later attested.

Ignatz Edballs faffed frantically with the control panel on his wrist, trying to halt his creation in its tracks. His efforts were in vain. At the last, he was alone upon the beach with his sand robot, the holidaymakers having fled. As the sun dipped below the horizon, horrified observers on the promenade watched as the huge implacable malevolent sand robot pursued its creator into the cold pitiless sea, the sea that had always terrified him, and now engulfed him, as he sank beneath the waves, and his sand robot, lethal and relentless, followed him, and crumbled, and was dispersed upon the waters of the earth.

EggPal

This morning I received an email from PayPal containing – among other things – this curious claim:

It had never before occurred to me that, when seeking to identify birds’ eggs, the first port of call should be a PayPal customer services person. However, now I know, and I shall be bombarding them with all my birds’ egg identification quandaries. You should do likewise.

ADDENDUM : While you’re there checking your birds’ eggs, don’t forget to give alms to the Hooting Yard Fighting Fund. (I’m not sure yet who or what we’re fighting, but don’t you worry about that.)

On Gulls’ Eggs

We have learned that the best place in which to store your collection of gulls’ eggs is a fogou. It is indubitably useful to know that. But what if you have no gulls’ eggs to store away? What then?

“Oh woe is me! for I have not two gulls’ eggs to rub together!” This is the plaintive cry of the otherwise happy fellow whose fogou lies empty. It is a cry that, however often heard, never fails to tug at the heartstrings, for those whose hearts have tuggable strings, which is most of us, or so I like to think, for I believe in the inherent goodness of humanity, despite all the evidence to the contrary. And goodness knows there is contrary evidence aplenty! I think it was Molesworth 2 who observed “Reality is so unspeakably sordid it make me shudder”, and even I can see the truth of that. So perhaps it is fair to say there is a measure of unreality about my belief in goodness. Real or unreal, however, I know that when I hear a poor benighted soul bewailing his utter lack of gulls’ eggs, I weep. I would like to think you would weep too.

But what can we do about it? No matter how copious and salty our tears, tears alone will not drum up a clutch of gulls’ eggs to give to the fellow bereft. Imagine if they did! If, as each tear rolled down our cheek, la!, we could pluck from the air a fresh gull’s egg and hand it, with great care, so as not to crush it, to the tenant of a gulls’ eggless fogou. Perhaps that is not so improbable as you may think. Sophocles, for example, believed that the tears of the birds known as the Meleagrides solidified into amber. Yes, yes, I know it is something of a stretch to conclude from that that the tears of good-hearted humans could solidify into gulls’ eggs, but it is at least worth holding in our heads for a little while. For were it so we could solve the whole problem of the poor fellow and his fogou and his lack of gulls’ eggs.

You will say that there are more urgent matters to be addressed in this vale of tears. War, pestilence, famine, disease, rust, inclement weather… all these, it is true, may place a greater strain on our heartstrings than the man without gulls’ eggs ever could. Are we, then, to cast him aside, like so much chaff? I have heard it said, by those whom I suspect subscribe to Molesworth 2’s tragic vision, that the man would be better off filling his fogou with chaff, and have done with it. Reluctant as I am to admit as much, there is some merit in this view. Chaff is easily gathered. One need not go clambering about on remote coastal promontories, at risk of toppling on to the sea-smashed rocks far below, to raid the nest of a gull for its complement of eggs. That, quite frankly, is going to be how you are going to get hold of some gulls’ eggs, because never in a million years, in Molesworth 2’s unspeakably sordid reality, will your tears solidify in some implausible Sophoclean fashion into gulls’ eggs, much as I might wish such a happenstance to occur.

There will have to come a point where the man ceases his plaintive wailing and settles for a fogou full of chaff rather than of gulls’ eggs. But the worst thing we can do is to slap him around the head and tell him to pull himself together and to go off chaff-gathering. No, we must break it to him gently, solicitously, tenderly. Let him dab at his tears with a rag, and lie on a lawn, and perform breathing exercises recommended by the most wise gurus from the mystic Orient. Then, when he is becalmed, we can begin, slowly, to turn his mind away from gulls’ eggs and towards chaff. One way to do this is to plant the idea in his brain that there is no such thing as a gull’s egg. How might we accomplish this? Well, if I may be permitted to interject a personal anecdote here, I think I can point the way towards a successful outcome.

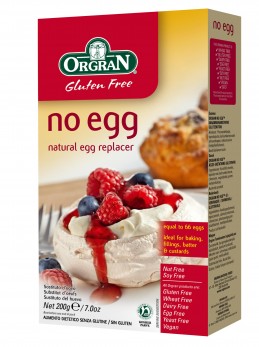

A few years ago, I fell in with a wizardy mindbender type of person, who managed to convince me – and I am not making this up – that there was no such thing as an egg. Not just a gull’s egg, but an egg, plain and simple. He did this by cleverly planting in my path, wherever I roamed, wherever I looked, at all times of day and night, cartons of the proprietary product known as No Egg. Thus assailed by the words at every turn – No Egg! No Egg! No Egg! – within a matter of hours I could no longer even imagine such an object as an egg. Thus we can obtain dozens, or hundreds, of cartons of No Egg, and modify them, using a magic marker pen or a crayon, to read No Gull’s Egg. Scatter them wherever the fellow might roam, wherever he might look, at all hours of day and night, and he will not long have dried his tears before he can no longer conceive of the existence of gulls’ eggs, and he will happily cram his fogou with chaff.

Advice Regarding Eggs

Here at Hooting Yard we are regularly inundated with queries relating to eggs. Here, for example, is a plaintive plea from reader Tim Thurn:

Q – When you are dining with an intimate friend, and an omelette au rhum is served, what do you do?

My spies tell me that Tim has copied out this question from Rambles In Womanland by Max O’Rell (1903), wherein the answer is given thus:

A – Without any ceremony, you take a spoon, and, taking the burning liquid, you pour it over the dish gently and unceasingly. If you are careless, and fail to keep the pink and blue flame alive, it goes out at once, and you have to eat, instead of a delicacy, a dish fit only for people who like, or are used to have, their palates scraped by rough food. If you would be sure to be successful, you will ask your friend to help you watch the flame, and you will even ask him to lift the omelette gently so that the rhum may be poured all over it until the whole of the alcohol contained in the liquor is burned out.

I might add that taking a spoon without any ceremony is easier said than done, but my remarks on that will have to wait for our series on spoons and ceremonies, which is forthcoming.

Orwellian Dabbling

Devoted Hooting Yardists will be familiar with the contents of Key’s Cupboard this week, where I bring to the attention of Dabbler readers the egg-counting antics of George Orwell. I often reflect – and by “often” I mean daily, daily – on the fact that two titanic figures in the cultural landscape of the twentieth century had such wildly divergent attitudes to eggs. There is Orwell, thin and wiry, with his love of eggs, and Alfred Hitchcock, plump and bloated, who was terrified of them.

It could be argued that Orwell was not an egg lover as such, that he merely had a mania for counting them, a mania that could have found expression in the counting of other farm (or smallholding) produce. Frankly I cannot be bothered to do the biographical research which would be necessary to write a monograph entitled George Orwell’s Attitude Towards Eggs. Perhaps someone else could take on that important task.