As regular readers know, here at Hooting Yard we always keep abreast of the latest twaddle in the zeitgeist…or perhaps I mean the latest piffle in the Weltschmerz. Either way, it behoves me to inform you that your esteemed editor has joined the teeming millions flocking to Facebook. If you want a glimpse behind the scuffed yet elegant portals of Hooting Yard, and to gain an insight into the enigmatic mechanisms by which this site is brought to you, come and join me.

Monthly Archives: June 2007

Becoming More Like God

I read in the paper today that the Archbishop of York’s press officer is himself being ordained as a priest. He has taken this step because, apparently, he “wants to be more like Jesus Christâ€. If we accept his belief system for a moment, what he is saying is that he wants to be more like God. Such overweening ambition is usually a worrying sign, and almost always delusional, and people who say things like that are likely to get locked up, or at least be given an Asbo. When his careers officer asked the teenage future press person what he wanted to be, did he answer “God!”, with a demented gleam in his eyes? His name, by the way, is Arun Arora, rather than Caligula, but you know the type.

Some may say there’s nothing wrong with setting your sights high, but if you’re going to become a god, Jesus Christ seems a poor choice. If it were me, I’d go for one of the more belligerent Aztec or Ancient Egyptian gods, or perhaps something epic and Nordic, like Odin, although I suppose the heavy metal associations would become something of an embarrassment. In the end, I think I’d plump for the hideous bat-god Fatso. There would be none of that nonsense with loaves and fishes, or getting crucified, but lots and lots of cakes and pastries.

All of which is an excuse to republish another item from the Archive, a piece entitled Cake And Pastry Person. It originally appeared in July 2006.

*

Many, many years ago, so long ago that you were probably not yet born, there was a cake and pastry person who drove a van around Pang Hill and Blister Lane, tooting a horn in the summer afternoons, for it seemed the sun was always shining in those far away days. Those were times when children still bought cakes and pastries from a van, a big pantechnicon painted yellow and red and pink and mauve and black.

It was also, of course, the time when people worshipped the hideous bat-god Fatso, and walked the earth in fear of his flapping wings and his shrill squeaking that churned up the innards and pierced the soul. Where, in other lands, the roads would be lined by milestones telling the distance to an important town or port, here there were hundreds and hundreds of huge stone carvings of Fatso, the visible reminder of his terrible, and terribly haphazard, power. Children were protected from the worst of his wrath, for Fatso the bat-god did not fully reveal himself until a person reached adulthood. For tinies, the stone statues were simply part of the landscape, like trees or kiosks or pneumatic power towers.

Although the bat-god is forgotten today, everyone remembers the resin hoops that were the favourite plaything of young and old alike. I am sure you know the words to the old song. “We skip and frolic and loop the loops / Along Pang Hill with our resin hoops / We skip and frolic on

These were the roads up and down which the cake and pastry person’s van would trundle, slowing to a halt whenever a little crowd of tinies gathered, each child clutching a cake and pastry token. In an excited gaggle, the children would exchange their tokens for cakes and pastries, and the cake and pastry person would collect the tokens in his token tin, which rattled when he shook it, and shake it he did, to hear that pleasing rattle. He beamed at the children as he handed out his cakes and pastries and took their tokens and rattled his token tin, but an acute observer might see that the beam was a false, rictus grin, for the cake and pastry person was plunged in melancholy. He remembered the innocent times when he, too, had been able to eat cakes and pastries without a care. Now, like every adult in the land, his days were consumed by a desperate need to placate Fatso the hideous bat-god. It seemed that Fatso needed more and more tokens every day, and the cake and pastry person was seldom satisfied until his tin was so crammed with tokens that it no longer rattled. Only then could he cease driving his pantechnicon round and round the roads, and park by the perimeter fence of the swan sanctuary, and take his tin, on foot, along the lane to Fatso’s cave, and wait, with all the other supplicants, for night to fall and for the bat-god’s lieutenants to shimmer into view. When at last his turn came, he would empty the tin into the outstretched paws of a greedy and grasping lieutenant, and plead for benediction, but benediction rarely came. Tomorrow, a bigger tin, more tokens. Thus was he commanded, in the horrible high-pitched squeals of Fatso’s inhuman myrmidons. One by one, then, they would flit away with their booty into the deepest, darkest recesses of the cave, and the cake and pastry person and all the other hunched and sorry believers would traipse away, back to their huts and shacks and cabins, and try to snatch a few brief hours of sleep before dawn broke and they faced a new day with redoubled effort. As they slept, the resin hoops rotted on the statues of their bat-god, poisonous weeds crept and curled along the ground, and in the nurseries, under cover of the night, tiny children giggled with delight, happy that they had bolstered Fatso’s power for another day, sure in the knowledge that tomorrow would bring more looping the loop with their resin hoops, more sunshine, and more cakes and pastries from the cake and pastry person’s yellow and red and pink and mauve and black cake and pastry van.

Up In The Mountains

Dobson and Marigold Chew were up in the mountains. Dobson was wearing an ill-advised cravat, while Marigold Chew sported a leopardskin pillbox hat. They were in pursuit of a murderer, reported to have taken refuge in the mountains. Their purpose was to persuade the murderer to repent his killing spree. They had no interest in bundling him back down from the mountains to face earthly justice. They simply wanted him to repent.

The murderer was Babinsky. Heavy of moustache and lumbering of gait, he had prowled the streets of

Lupus, neither ursine nor lupine but human, is an unaccountably popular disease in the television medical drama House M.D. Intriguingly, Dobson and Marigold Chew had arranged their trip to the mountains by buying tickets from a travel agency named Foreman, Cameron & Chase. These are the names of Dr House’s young assistants. In a further twist so improbable that it could almost be fictional, the conductor on the train that brought them to the station at the mountain foothills was a man called Cuddy Wilson. Cuddy and

Let us treat ourselves to a bird’s eye view of the terrific mountains. If we imagine we are hovering directly above them, hundreds of feet in the air, at cloud level perhaps, we can draw a triangle between three points. Call them A, B and C. At A, we have the snackbar in the foothills, wherein we find Dobson and Marigold Chew. At B, we have an encampment of mountain bears, many stricken with ursine lupus. And at C, the killer Babinsky, taking shelter in a declivity that might be a crevasse, high in the mountains, examining the contents of his knapsack, packed in a panic as he made his getaway from

So there at point C, the disconsolate Babinsky rummaged among the items he had packed panic-stricken into his knapsack. Instead of useful things like a compass and pemmican and string, he found that he had a paperback Gazetteer Of Basoonclotshire, a tattered pincushion innocent of pins from which half the stuffing had fallen out, a photograph of a pig, two corks, an unpaid gas bill, a badge from Richard Milhous Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign when he ran against Hubert Humphrey, several small and purposeless cloth pods, a rusty whisk, a paper bag full of bent or otherwise damaged fountain pen nibs, the packaging from a black pudding he had eaten just before he killed the toothless vagrant of Pointy Town, hair dye, a plasticine starling, much dust, a cardboard tag or tab or label on which some unknown functionary had scribbled the word pointless, a beaker caked with mould, another beaker with a gash in its base, a sleeveless and warped 12†picture disc of Vienna, It Means Nothing To Me by Ultravox, whittled twigs, scrunched-up dishcloths, the gnawed bones of a weasel, or possibly a squirrel, feathers, a pictorial guide to cephalopods, someone else’s illegible address book, an empty carton of No Egg, more dust, more feathers, more bones, and a syringe containing a goodly amount of ursine lupus antidote. Having neatly laid out all this rubbish on a ledge in the declivity or crevasse where he squatted, Babinsky stuffed it all back into his knapsack, made the knapsack a pillow, lay splayed out on his back, and fell asleep.

Meanwhile, over at point B on our triangle, the many, many, many bears, both those with ursine lupus and those without, were also fast asleep, and had been for some hours. It was as if they had been engulfed by some sort of narcoleptic gas, but those with knowledge of the mountains, and of the mountain bears, would tell you that there was nothing to worry about. It was simply a case of an encampment of sleeping bears, high in the mountains, who would eventually wake up. Down in the foothills, village folk might tell stories about the mysterious experiments going on in the Pneumatic Institution for Inhalation Gas Therapy, but they knew not whereof they spoke, for they were peasants rather than scientists, and thus their expertise was in such matters as slurry and pigswill and barnyard maintenance rather than in exciting gas activity. In any case, by skipping along to point A, one would find Dobson and Marigold Chew in the snackbar, wide awake and intently planning their next steps in tracking down the killer Babinsky and making him repent.

Ever resourceful, Marigold Chew had brought her Ogsby Steering Panel to facilitate the search. Neither she nor Dobson could be said to be natural mountaineers, both of them more at home on flat surfaces such as ice rinks and tidal plains. Yet they had a sense of overwhelming duty to make the killer repent, preferably on his knees, or sprawled on the ground in a posture of abject grovelling, not unlike Pong Gak Hoon, from which Dobson was only just recovering with the help of the tremendous snackbar breakfast menu. So enthusiastically was he stuffing his gob that Marigold Chew began to wonder if her paramour would be too bloated to clamber in sprightly fashion up into the mountains before nightfall. She was well aware, even if Dobson was not, that at night-time these mountains were both eerie and perilous, for all those years ago she had paid attention in the prefabricated schoolroom when Miss Hudibras taught the important Key Stage 4 Sprightly Clambering In Mountains At Night learning module.

And it will be night, star-splattered and moonstruck, before the three corners of our triangle are each set in motion, and begin, ever so slowly but implacably, to converge upon each other, the triangle twisting, warping like Babinsky’s Ultravox record, shrinking. Dobson and Marigold Chew, the killer Babinsky, and many, many, many bears, including those stricken with ursine lupus, will meet, in the most desolate hour of the night, up in the mountains, at a spot we can call point D. And here at point D, as if awaiting them, bashed firmly into the hard compacted snow, stands an upright cylinder of reinforced plexiglass, sealed with a rubber cork. It is one of a number of cylinders placed here and there in the mountains by boffins from the Pneumatic Institution for Inhalation Gas Therapy. And as the peasants down in the foothills could tell you, as they pause in their doings with slurry and pigswill and barnyard maintenance, only the devil knows what some of those boffins are up to. And as I can tell you, even though I am no devil, there were rogue elements among the boffins, bad boffins, and one such boffin had, just yesterday, filled the cylinder at point D with a new and terrible and loathsome gas which, when uncorked, would fell all living things within a twenty yard radius, crumple them as if they had been placed in the Pong Gak Hoon posture beloved of Goon Fang adepts like the Babinsky-double train conductor, and their brains would be modified in gruesome and unseemly ways. And then, as the gas dispersed into the clear mountain air, as dawn broke, each of them would awaken, Dobson and Marigold Chew, the killer Babinsky, and many, many, many bears, including those stricken with ursine lupus, and to each of them the world would seem raw, different, alive with new tangs and hues and vapours, and the three points of the triangle would slowly move apart, relentlessly, forever, as if they had never, ever converged.

Coleridge, Roget, And Gas

Reviewing a new biography of Peter Mark Roget by Nick Rennison, Steven Poole notes “Roget studied medicine at

In Ponga

In Ponga, you can recognise the satraps because they wear plumed hats. Or so I am told. In Gooma, by contrast, the hats of the satraps are unplumed, and look like any other hats sported by a million other Goomans. The satraps can be distinguished by their tattoos. Pongan satraps eschew tattooing, which is reserved for their shamen, but there are no shamen in Gooma. If one flies over the mountains into Gaar, one finds that the satraps wear plumed hats and sport tattoos, and that the chief method of adverting to their satrapdom is their habit of always carrying a bundle of tally sticks. The shamen of Gaar have both plumed hats and tattoos, but they do not carry tally sticks. They tie their hair in complex stylised knots.

This much I have learned, and am grateful to have learned, from a fascinating periodical entitled Satraps And Shamen Of Ponga And Gooma And Gaar. It is published on the first Thursday of each month, and is packed with articles and photographs and quizzes and competitions. Since I picked up a copy at a newsagent’s in an esplanade on a mezzanine level at an airport a short while ago it has become my absolute favourite periodical ever, even though I had no previous interest in either satraps or shamen, whether they were from Ponga or Gooma or Gaar or any other country you care to mention. I have been won over by the magazine’s excellence in all particulars, but mostly by its vividness. It is the most vivid of periodicals, more vivid even than the Reader’s Digest.

In Ponga, the satraps hold councils at which are discussed important meteorological issues. The Pongan shamen consider the weather to fall within their purview, and this can lead to clashes between satraps and shamen. Such clashes are conducted at a strictly verbal level, and give rise to some fascinating linguistic quirks. Because there are no shamen in Gooma, the Gooman satraps have the weather all to themselves and face no clashes. In Gaar, the shamen tie their hair in complex stylised knots.

I have said that Gaar is on the other side of the mountains from Ponga and Gooma, but I have yet to learn what these mountains are called, or indeed where they are. Vivid as the periodical is, I have to say that it is unforthcoming on matters geographical, and that is an understatement. I have been toying with the idea of writing a letter to the editor suggesting that a future issue might include some maps. When I was a little chap I had a passion for maps, just like the narrator of Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness. I am no longer a little chap at all, but I would like to see maps, colourful ones, of Ponga and Gooma and Gaar. They would make the periodical even more vivid than it already is.

In Ponga, the satraps have dominion over the birds of the air, or at least they act as if they do. They devise many laws to which the birds of the air are subject. Flightless birds fall within the remit of the shamen of Ponga. They do not create laws, but they consider flightless birds to be sacred, and count them, often. The satraps count the birds of the air also, with different purposes in mind. In Gooma, all known birds are poultry. In Gaar, the satraps carry tally sticks and the shamen tie their hair in complex stylised knots.

I stumbled upon my first copy of the periodical in that newsagent’s in an esplanade on a mezzanine level at an airport quite by accident. I was due to board a flight to a remote prison island, where I had been asked to sluice out the convicts’ brains with an exciting and dangerous new fluid. I had a few minutes to spare before my flight and went to pick up the latest Reader’s Digest. Repair work was being done to the newsagent’s frontage, so I had to squeeze in through a side panel, thus entering a part of the shop I would normally not have explored. Most of the racks here were stacked with fruit pastilles and pastry snacks, and I have no need of these things, for when travelling I always bring my own food. A single copy of the September issue of Satraps And Shamen Of Ponga And Gooma And Gaar lay atop a tinderbox on the floor next to a display of packets of jammy teardrops. I picked it up out of curiosity and was struck by its vividness.

In Ponga, the satraps have a counting system of astonishing complexity. It is possible that their brains are wired in a way unique to them. The shamen count as you or I would count, although as you would expect they use different words for numbers. The satraps do not even use words when they count. Nor do the satraps in Gooma, but that is because they do not count at all. The Gooman satraps pipe and hum in place of counting. They manufacture spikes and nails and do a lot of purposeless hammering. In Gaar, the satraps carry tally sticks.

The publishers do not make a binder available in which to keep copies of their vivid periodical, and this is another matter I planned to raise in my letter to the editor recommending the inclusion of colourful maps. I am extremely keen on binders for periodicals, whether or not they are vivid. It is true that I have quite a number of loose unbound periodicals in my collection, and that pains me. I numb the pain with prayer, for that is what the Bishop of Southwark told me to do. When some of the more promising convicts had had their brains sluiced with my exciting and dangerous new fluid, I set them a project to make binders for my unbound periodicals, including Satraps And Shamen Of Ponga And Gooma And Gaar. They made an excellent fist of it, with limited resources, and I like to think that the sluicing had much to do with that.

In Ponga, the satraps make regular changes to the plumes in their hats according to the phases of the moon. The shamen take no notice of the moon, for they owe fealty to the sun. In Gooma the satraps believe that the health of their poultry is dependent upon the stars. In Gaar, the satraps carry tally sticks and the shamen tie their hair in complex stylised knots. I have counted all my binders, and I am carrying a tally stick, and later today, after I have watched the news bulletin and weather forecast on television, and had a little chat with the Bishop of Southwark, I am going to tie my hair in complex stylised knots.

The Numan Question

A generation ago, the aeroplane pilot and sage Numan asked “Are friends electric?†It was pertinent then, and is perhaps more so now. Over the years, many thinkers have grappled with Numan’s question, but it is fair to say that none has been able to give a satisfactory answer. Much publicity was generated when Pilbrow published his big fat Symposium on the problem. The garlanded laureate of pseudo-sci fi hermeneutic psychobabble persuaded over a hundred movers, shakers, and hysterics to respond to the poser put by Numan, and then toured the radio and television studios giving inaccurate summaries of their replies. Few who saw it will forget the Newsnight appearance when Pilbrow’s pretensions were comprehensively demolished by weatherman Daniel Corbett, who strode across the set from his meteorological map and literally tore a copy of the Symposium to shreds before Pilbrow’s – and Jeremy Paxman’s – eyes. It was a cheaply-produced paperback edition of the book, with weakly-glued binding, but Corbett’s feat was no less impressive for that.

Since that watershed, there have been other, muted responses to Numan, appearing for the most part tucked away in little-read specialist journals or inserted at the tail-end of lectures delivered in draughty, half-empty civic halls in the depths of winter. The question remains cogent. The responses have, almost invariably, shirked its implicit challenge.

Until now. For last week, Blodgett commandeered space in all the major newspapers to announce his answer. “Are friends electric? No!†it read, in big bold letters, and then, in smaller type, continued “Not my friends, at any rate. My friends are made of gas.â€

Blodgett went on to describe the small band of his pals who appear to him in the form of clouds of luminous, and sometimes volatile, gas. Anticipating the charge that he is subject to hallucinations, he refutes it with aplomb. Blodgett’s gas friends shimmer around him, he says, ethereal, mercurial, and insubstantial, but boon companions still. He gives the example of his friend Abu Qatooba, a friend composed of particularly volatile gas, an Islamic fundamentalist gas-form forever railing against the iniquities of pretty much everything he disagrees with and threatening to behead sinners and apostates and infidels. Blodgett is himself an infidel, of course, and this has led some critics to claim that he is making up all this stuff about a gang of friends made out of gas who hover around him. He is keen to dispel the impression that his chums are ghosts or wraiths. “They are as real as you or I,†he writes, “Completely human, with human virtues and vices. But they are formed of gas clouds. Abu Qatooba and I disagree on many points, but I count him as my friend because I admire his striking beard, also of course made out of gas, and his amusing tendency to fly off the handle at tiny provocations.â€

Blodgett gives fewer details of his other gas-pals, although he finds room to mention Daisy Blunkett, a blind widow-woman with a gas guide dog, and Anhopetep, an ancient Egyptian gas pharaoh. He explains that when they are not by his side, his friends flit from place to place, sometimes together in a gang and sometimes apart, and try to strike up friendships with others. They have met with little success in doing so, and Blodgett puts the blame firmly at Numan’s door.

“Intentionally or not, Numan planted the idea in people’s heads that in future their friends would be electric,†he writes, “Thus today’s citizens are less open to the idea that they may have friends made out of gas. This is a great pity. I have found companionship and joy with my little band of gas pals. They have much to offer in the hurly burly of contemporary life, and I urge each and every one of you to put out the hand of friendship to members of the gas community. Next time you are waiting at the bus stop and notice a cloud of luminous gas approaching you, take that bold step. Shed your Numanoid prejudices and greet that gas-cloud as a compadre. You can make a difference.â€

Blodgett has been hoping to appear on Newsnight to further his cause, but the producers are somewhat wary after the Pilbrow incident, and have no plans to invite him on to the programme.

The Lion Of The Olympics

I have been giving further thought to that logo – or brand – for the 2012 Olympics. Clearly the £400,000 design is a hideous mistake and will have to be ditched and replaced at some point within the next five years. My own view is that the organising committee ought to take a cheerful, jolly image from an already proven successful brand, slap the Olympic rings on it somewhere, and have done with it. What could be better than a picture of a lion being attacked by a swarm of Africanised killer bees?

The Sick Pig

Once upon a time there was a pig. It was a sick pig. Now, in a town far away across the hills there lived a vet. The vet had undergone many years of training in the veterinary sciences, and numerous diplomas in frames hung on the walls of his surgery. The surgery was a clean bright building in the middle of a row of slightly shabbier buildings in the centre of the town far away across the hills from the sty where the sick pig ailed. Next to the surgery was a pie shop, and next to the pie shop was a haberdashery and next to the haberdashery was the town hall annexe. On the other side of the vet’s surgery from the pie shop was a second pie shop, and next to that was the library, and squeezed in next to that was a kiosk selling tickets for local events and entertainments and next to that was an ironmongery. Beyond the ironmongery was the bus station.

The frames in which the vet’s many diplomas were displayed had been made by a framer on the other side of town. One day, the vet rolled up all his diplomas and shoved them into a cardboard cylinder, and waited at the bus station. He caught the number 666 to the other side of town and gave the cylinder to the person behind the counter at the framers’, who filled in a receipt from a pad of receipts and gave it to the vet, who put it in his pocket. Six weeks later the vet went to collect his many diplomas, now beautifully framed, and he carried them back to his surgery on the 666 bus and hammered nails into the walls of his surgery and hung the frames on the nails. Now he had all his diplomas on display.

If the diplomas were to be believed, the vet had demonstrated the ability to cure the ills of horses and bats and birds and toads and cats and killer bees and shrews and weasels and ducks and chickens and otters and badgers and field mice and cows and bears and hamsters and even giraffes, but not one of his diplomas had a word to say about pigs.

Now, the piggery person whose pig was sick, upon discovering the pig’s sickness, tried out a number of folk remedies, old and new. He sprinkled the pigsty with tansy and frangipani and gloxinia. He went to see the Woohoowoodihoo Woman, who gave him a spell to cast. He set up a loudspeaker in the pig sty and played In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida by Iron Butterfly, over and over again. He took tips from books by Tony Buzan. But the pig stayed sick. In fact it got worse. The piggery person was at his wits’ end. Then he remembered hearing about the vet in a town far away across the hills.

Leaving the assistant piggery person in charge, the piggery person set off on the long journey across the hills. On the first day he met a man dressed all in green who set him a challenge. The piggery person bashed him about with a bludgeon and went on his way. On the second day he was engulfed in a vaporous mist and had to use his torch to find his way through it. On the third day the man dressed all in green stood in his path again, so this time the piggery person felled him with a Goon Fang manoeuvre. On the fourth day, from the very top of the high hills, he saw the town nestling in the verdant vale below and a gigantic, mythical bird, a bit like Sinbad’s Roc but bigger, plucked him with its talons and soared down into the town and deposited him in front of the vet’s surgery.

The vet was out on call at an owl sanctuary, so while waiting for his return the piggery person studied the many diplomas hanging in their frames on the walls. He was dismayed to note that not one of the diplomas announced the vet’s skills at curing sick pigs. He resolved not to fret, but to question closely the vet upon the vet’s return to his surgery. He sat down in the waiting room and leafed through some of the Dobson pamphlets scattered higgledy-piggledy on the table. He became so engrossed in a pamphlet entitled The Man Who Put The Bee In Beelzebub that he did not notice the vet skipping jauntily back into the surgery, even though his entrance set a bell a-jangling. When the piggery person looked up from the pamphlet, the vet was looming over him. It was the man dressed all in green he had twice encountered on his journey!

“Twice we met and twice you knocked me aside, now here you are where I abide,†rhymed the vet, in a voice high-pitched, wheedling and malevolent. The piggery person shrivelled in his seat.

“Your pig is sick, and I shall cure it, but you will have to pay a forfeit,†said the vet.

He pointed his long bony finger at the piggery person, and sparks flashed, and there was a puff of inexplicable roseate vapour. When it dispersed, the seat where the piggery person had been sat shrivelling was revealed to be empty. At the same moment, far away across the hills at the piggery, the assistant piggery person was beflummoxed to see the sick pig cured, cured and thriving. It grunted happily and trotted out to scrubble in the muck. There was a big black beetle in the muck.

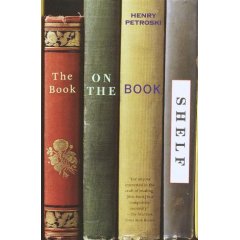

The Book On The Bookshelf

Here are twenty-one suggested ways of arranging the books on your bookshelves.

1. By author’s last name, 2. By title, 3. By subject, 4. By size, 5. Horizontally, 6. By colour, 7. By hardbacks and paperbacks, 8. By publisher, 9. By read/unread books, 10. By strict order of acquisition, 11. By order of publication, 12. By number of pages, 13. According to the Dewey Decimal System, 14. According to the Library of Congress System, 15. By ISBN, 16. By price, 17. According to new and used, 18. By enjoyment, 19. By sentimental value, 20. By provenance, 21. By still more esoteric arrangements.

Taken from The Book On The Bookshelf by Henry Petroski, where you will find a splendid little essay on each arrangement. Petroski also wrote a marvellous book about pencils, called The Pencil.

Tidy Is As Tidy Does

Dobson was an excessively tidy man. He firmly believed the old saw which insists there is a place for everything, and everything in its place. Thus, he kept sweets in jars, and jars on shelves in cupboards. This despite his loathing of confectionery. When asked why he stored so many sweets, including humbugs, toffees and jammy teardrops, in labelled jars on labelled shelves in labelled cupboards, Dobson blustered and tried to change the subject.

“Oh look,†he might say, pointing out of the window, “A mother shrike with her shrikelets,†or “What would you say were the chief causes of the Boxer Rising?†In the latter example, he would not bother pointing out the window, but might furrow his brow, as if he had been pondering the topic for some time.

This sneaky yet transparent technique worked surprisingly often. Few people, other than Marigold Chew, felt confident enough in the pamphleteer’s presence to challenge Dobson. The explanation for this lies not in any personal magnetism or force of personality. In fact, for the life of me I cannot think why he got away with his preposterous behaviour.

Cutlery alignment in cutlery drawers was another type of tidiness which exercised the great man. At particularly fraught times he was known to align and realign the cutlery in the cutlery drawer ten times an hour. Sometimes he would be halfway along the path to the pond to commune with swans, then turn on his heel and stamp back into the house to attend to the knives and forks. Nowadays, of course, some pop psychologist would make a television documentary asserting that Dobson suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder, but I think we can safely reject such a notion. It is not as if he was washing his hands every five minutes, or going doolally at the sight of glitter. Indeed, he ought probably to have washed his hands more often. They were invariably ink-splattered and grubby in other ways, particularly if he had been down by the pond with the swans. No, I think we can rely on Dobson’s own account of the cutlery issue, which he addressed in a pamphlet entitled Keeping Cutlery Aligned Tidily In The Cutlery Drawer As An Absolute Imperative If One Aspires To Be Fully Human (out of print). For reasons I need not go into here, hardly anybody has ever bothered to read this middle-period work. The prose is clogged and clunky, the views expressed idiotic, and when typesetting it Marigold Chew chose so tiny a font that the average reader needs an extremely powerful magnifying glass to decipher the text.

Oh, forgive me, I just went into the reasons why hardly anybody has ever bothered to read this middle-period work. Dobson would ascribe that little slip to the fact that the cutlery in my cutlery drawers is chaotic and askew. Am I not, then, fully human? And if not, what am I? Partly ape? Perhaps I would be able to answer those questions if I myself had read the pamphlet, but I confess I have not done so. My eyesight is not up to it. I could, perhaps, employ some bright-eyed literate youngster to read it to me, a perky little brainbox uncowed by Latin tags and arcane references and paragraphs that go on and on and on for twelve pages or more, by clogged and clunky prose and idiotic views, but where would I find such a creature? I suppose I could take a stroll in the rain down to the nearest community hub, but that would be the act of a desperate man. Better by far, surely, either to accept my semi-human status, to give vent to my inner ape and to stuff my face with bananas and nuts, or conversely to go and align the cutlery in the cutlery drawer with Dobsonian precision and thus destroy the ape that lurks within me. It is a simple choice, and one I shall not shirk from making.

The Huffington Post

Whenever bumpkins gather of an evening in the shack at the end of the lane, sooner or later their talk will turn to the Huffington Post. It is not uncommon for the peasantry to fixate upon minutiae, of course. We think of Old Farmer Frack, obsessed with his bellowing cows, or the eerie barn at Scroonhoonpooge, or any number of pig-related outbreaks of countryside mass hysteria, often focussed upon something as insignificant as the shape of a newborn pig’s snout or trotters. Yet the bumpkins’ preoccupation with the Huffington Post was curious, for to the untrained eye it looked like any other fencepost or stake or piece of paling. I dare say you or I would pass by that post without giving it a glance, and the prattle of the bumpkins of an evening in the shack at the end of the lane would sound to us nonsensical. But rustic wisdom is hard won, and only a fool would dismiss the bumpkins’ shack chatter as drivel.

On a balmy evening one such fool blundered into the shack at the end of the lane and, hearing the bumpkins bandying the profundities of Huffington Post lore, took it for the idiocy of defectives. With his briefcase and bowler hat it was clear the fool dwelt in a city. Clear, too, that he could not tell the Huffington Post from any other posts and stakes and pales thumped into the muck for fencing the fields. His manner and his smirks were disparaging of the bumpkins, and when he left the shack and was making his way to the railway station, they waylaid him and carried him off to the eerie barn at Scroonhoonpooge. And as they had done with others who came to mock, they coated him in farmyard slurry and tar and poked him with pitchforks, and when they were done with him they buried him at

Himmelfarb

Please note that access to HIMMELFARB is restricted. Within five seconds a new window will open, in which you should type your access code.

If you do not have an access code yet, where have you been? To get an access code, albeit a late one, you must subscribe to the HIMMELFARB Groupuscule Register. Your unique access code can be retrieved from the database when you receive a confirmation email, unless you are a seedy person, in which case it will be sent by carrier cyberpigeon.

Your access code is different from your password, but must be compatible. For help with access codes and passwords, and to check compatibility, you need to download a .pdf file from the HIMMELFARB Document Storage Mirror Site closest to you. A list of locations is available to unregistered users via wingrotesque.

If the new window has not opened within five seconds, there is either something wrong with your computer, or you have a deeply flawed personality. You may even be a seedy person. It is not unknown for the seedy and dissolute to try to gain access to HIMMELFARB, more’s the pity. But the system is robust and we have a proven track record of filtering out such deplorable specimens. Less sympathy, more deploring, that’s our motto. Much more deploring. Deploring and condemning.

To view the readme file on our vindictive methods of condemnation, you will need to install a plug-in. You can do this even if you are a deplorable and seedy person, because the software has been developed in full cooperation with the Holy See in Rome. Upon installation, your computer will be imbued with Virtual Sanctity (version 4.03) with automatic upgrades. If you are a confessor of a different faith, there is no hope for you, no matter how often you sprawl on your prayer mat or slaughter a sacrificial goat. You are advised to repent your sins before it is too late, and your raiment is torn in shreds and your mouth is filled with ashes.

We are always seeking to improve the quality of users’ HIMMELFARB experience, and we welcome feedback, so long as it is grammatically correct. Those of you who write in as if you were a teenage nitwit sending a text message on a mobile phone will be subject to condemnation so robust that you will wish you had never been born.

Soap Flakes In A Box

Dear Mr Key, writes Tim Thurn, I couldn’t help noticing that in the piece about fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol’s training regime, Dobson repeatedly refers to “soap flakes in a boxâ€, without telling us which brand of soap flakes the champion sprinter used. This is a pity. I cannot be alone among your readers in having world-shuddering sporting ambitions, and I try to replicate the fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol approach in every particular. I have gone so far as to make my coach wear an East European raincoat and to chain smoke at the side of the track while I scamper round it. I grant you that she looks absolutely nothing like Old Halob, and is about half a century younger than he was at his peak, but you’d be surprised how effective the illusion can be, especially when she starts hawking up gobbets of phlegm just like the cantankerous old rogue.

Incidentally, I am on the lookout for a black Homburg she can wear to make her look even more like Old Halob, so if any of your readers know where I might get a genuine 1940s Homburg, perhaps they could contact me through your Comments section. I’m afraid I do not know my coach’s hat size, and nor, I suspect, does she. Gone are the days when people were as familiar with their hat size as with their shoe size. It is all chips and PINs now, but that doesn’t wash with me. I still sprinkle cash about, whenever I go roaming, not that I have much time to roam given my busy fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol-like training schedule.

Which brings me back to the matter at hand, namely those soap flakes in a box. Was Dobson leery of advertising a brand name, or what? I am aware that he was, or at least tried to be, a pamphleteer of considerable moral fibre, but that seems to be taking things a bit far. I am sure his legion of fans would have thought no less of him if he had bandied brands like Omo or Daz in his pamphlets. When you consider that towering intellectual figures of our own day such as Isaiah

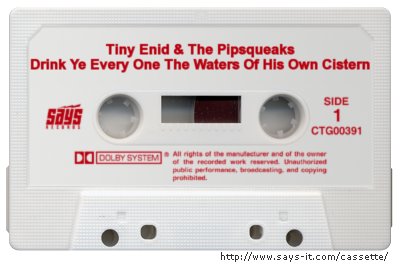

Rummaging In An Abandoned Satchel

The other day I had some harsh words to say about the out of print pamphleteer Dobson’s song-writing skills. “No one with any sense has ever listened to a Dobson song more than onceâ€, I wrote. Well, it seems I was mistaken. I was rummaging in a satchel that I found abandoned on a canal towpath, and I came upon indisputable evidence that at least one sensible person admired a Dobson song so much that they recorded a cover version of it. The song in question is one of the pamphleteer’s settings from the Book of Isaiah.

Hooting Yard readers are a wise bunch, and I would not be surprised to be deluged with letters accusing me of making up the whole satchel-rummaging incident in some foolhardy attempt to chivvy up Dobson’s reputation. I therefore arranged for a local snapper to take a snapshot of what I found, as proof.

Thanks, by the way, to boynton.

Boot Bath

He washed his boots in the bath with a scrubbing brush. That is what he did when he got mud on his boots. He took off his boots and placed them on a mat and he filled the bath with boiling water. Then he plunged his boots into the bath. He put on a pair of gloves before he plunged his boots so the flesh on his hands would not burn. When the boots were in the bath he sprinkled soap flakes from a box on the surface of the boiling water. Then he went to fetch the scrubbing brush. The scrubbing brush was nowhere near the bath, he had to go up and down stairs to get it from its hook. There was a hole drilled in the handle of the scrubbing brush so it could be held by the hook. The hook was fixed to the wall. It was a fixture and fitting. The scrubbing brush was not. It was an appurtenance. He neither knew nor cared which was a fixture and fitting and which was an appurtenance. His only concern was to get the mud off his boots. He scrubbed his boots with the scrubbing brush while the boots were submerged in the bathwater to which he had added soap flakes from a box. The mud came off his boots in chunks. When the last flecks of mud had been scrubbed off his boots he took the boots out of the bath and placed them back on the mat. The mat was made of rubber. He pulled the plug out of the plughole in the bottom of the bath and the bathwater drained away. While the water drained he took the scrubbing brush up and down stairs and put it back on its hook. He tore off his gloves and threw them down a chute. At the bottom of the chute was a pile of other gloves and such things as shirts and socks and tunics. Once a week the pile was swept into a hamper and taken off to be washed. But not today. He went up and down stairs to the room with the bath in it and looked at his boots on the mat until they were dry. Then he put on his boots. Just in time! He heard the toot of a whistle. He sprinted up and down stairs and past the place where the scrubbing brush hung on its hook and carried on out of the door and through the garden gate and he sprinted round and round the running track until the whistle tooted again. He stopped and panted and looked expectantly at the whistle tooting person. The whistle tooting person was studying his stopwatch. O how he hoped that this time he had sprinted round and round the running track faster than the last time he had sprinted round and round the running track! Then he had had mud on his boots but now he had washed them in the boiling hot bath with a scrubbing brush and soap flakes from a box and there was no longer any mud on his boots. A nod from the whistle tooting person told him he had sprinted round and round the running track faster than before. He was O so happy!

From The Happy Sprinter : An Eye-Witness Account Of The Training Schedule Of Fictional Athlete Bobnit Tivol Under The Direction Of His Coach, Old Halob by Dobson (out of print)