There are some questions we can answer without hesitation. Asked “what is your favourite website?â€, one hundred percent of sensible people immediately shout “Hooting Yard of course!†with unhinged and hysterical enthusiasm. Similarly, when asked in which schoolbook depository they would prefer to site a sniper’s nest, an overwhelming number of would-be assassins reply “the Texas Schoolbook Depository at

Each week, I followed the adventures of the chirpy pair with my jaw dropped and drool flowing freely down my chin, my heart and pulse rates pounding desperately. It was through Buster and Radbod that I learned to read, and I am forever in their debt.

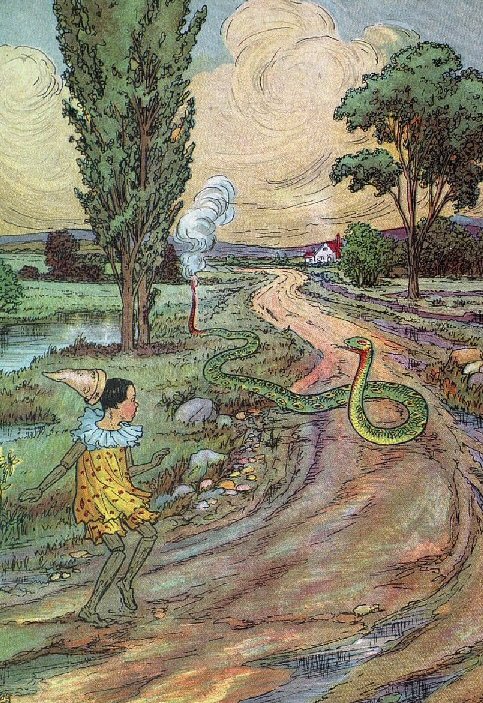

They were, in many ways, an ill-matched fictional pair. Buster was squat, hissy, and preening, given to throwing fits and always attired in a bright yellow duffel coat and a little pointed wooden cap. He existed on a diet of chocolate swiss rolls, sprats, lettuce, and untreated milk straight from the goat. We were never given a glimpse of the goat, but it was understood that it lived in a field a short walk across the verdant hills from Buster’s house and that its name was Buttercup. Buster had more than one iron pail in which he would collect the milk, one painted red and one unpainted, and a third, extra special pail that leaked and that he was always promising to mend, but never did. Buster had too many teeth crammed inside his mouth, certainly more than a non-fictional person would have, and some of them were sharpened into fangs. He liked to sit atop a rotating plinth and spin round and round until he was sick. I was always curious as to the engine which rotated the plinth. It bore a distinct resemblance to undersea drilling equipment I had seen, either in real life or in catalogues, although of course nearly all of Buster and Radbod’s adventures took place on dry land, far from the sea. Buster was once or twice shown to be in possession of a pair of swimming trunks, they were visible in pictures of his open wardrobe, alongside a snorkel and an oxygen canister, but I cannot recall him ever wearing them. Buster had an owl as well as a goat. The owl was also called Buttercup, and Buster treated it cruelly, often pelting it with the shells of pistachio and brazil nuts throughout the impossibly long afternoons of his idyllic fictional summertime. The owl took its revenge by regurgitating gobbets of semi-digested stoat or weasel on to Buster’s pointed wooden cap, which he would then have to rinse clean under the village spigot. Doing so was always a risky business, for lumbering in the vicinity of the village spigot was the village wrestler, a hairy brute capable of tearing an anvil in half with his great hairy hands. Luckily for Buster, the village wrestler was chained to a post next to the village spigot, and he was blind, so usually it was possible to skip nimbly out of his reach, even though, being squat, Buster was not the most nimble of cartoon characters. Indeed, he was not nimble at all. He slouched and he trudged and he often trailed one of his legs behind him, as if he were a lame child, but this was just rascality. Buster pretended to be lame to diddle small coinage from shopkeepers and the ground staff at the aerodrome, but most of them were wise to his tricks. In quite a few stories Buster and Radbod mooched around the aerodrome, trying to enter the hangars, but they were invariably stymied by one circumstance or another, be it the weather or early closing or an attack of killer bees or a rusty padlock. Once they were about to step into an unguarded and unlocked hangar when they were surprised by the ghost of Sylvia Townsend Warner and fled screaming into the hills. Other literary phantoms haunted the comic strip from time to time, for differing narrative purposes, and not always at the aerodrome. The ghost of Emily Dickinson, for example, hovers in mid-air outside the village shampooist in several frames of a particularly exciting adventure in which a toggle on Buster’s duffel coat is discovered to be a smooth round fragment from the tomb of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh. Buster hires a broom to fight off the ancient Egyptian ghouls who come to reclaim the pharaoh’s toggle. The hiring of brooms, sweeping brushes, dusters, squeegees, rags and other cleaning materials is one of Buster’s hobbies, along with bell-ringing, stamp collecting, making fluted paper cupcake cases, pelting his owl with the shells of pistachio and brazil nuts, First World War battle re-enactments, tongue twisters, snakes and ladders, playing songs from the Fort Mudge Memorial Dump LP on the glockenspiel, churning up froth in a pail, bandage sculpture, tick tack, tacky tock, driving nails into mud idols, Subbuteo table football, poop tack clatter tack whizz, ping pong, hopping about flapping his arms, conjuring tricks, removing splinters from gashes, cardboard appreciation, amateur dramatics, pencil sharpening, scattering pins all over the place, bowling, bowls and dishes, and running a flea circus. I thought of Buster rather than Radbod as a role model. Buster had nonchalance, élan, a filthy temper, a ready wit, and peevishness. He was insouciant when one of his lungs collapsed. He smoked Gitanes. He sometimes wore his pointed wooden cap at a jaunty angle. He could hold his breath under water for several very very tense minutes. He rattled about in a fantastic old jalopy. He had ambitions to be a bargee on an extensive system of canals. He was a dab hand with a banjo, and not in a musical sense. Once, he felled the blind brute village wrestler with a simple flick of his duffel coat cuff, and afterwards had the grace to polish the blind brute village wrestler’s chain with a hired rag and his own home-made swarfega. He dazzled at cocktail parties. He spat upon hissing coals. He tiptoed from rooms with a swish of elegance. He was off on a frolic of his own.

Radbod, by contrast, was a somewhat colourless character.

Recently I learned that a complete set of The Hammer Of Christ, bound in the hide of a cloven-hooved beast of the barnyard, and containing all the adventures of Buster and Radbod, will be for sale at an auction to be held at the dilapidated Custom House by the harbour steps in the stinking seaside resort where I usually spend my holidays. I am by no stretch of the imagination an experienced auction-goer, and I have no idea how to make a bid. Do I nod, or raise an eyebrow, or hold up a pencil, or flail my arms around? I do not want to cut an idiotic figure, but nor do I want to miss the chance to get my hands on such a treasure. It is a quandary, to be sure.

Having given it much thought, I have decided to take my lead from Buster himself. In one episode of this most marvellous of comic strips, he goes to an auction at a Custom House, not unlike the auction at the Custom House I plan to attend, and, when the lot he covets comes up, he sneaks outside and, through an aperture, pumps into the auction room a fast-acting nerve gas. Or maybe it is just any old gas, I can’t quite remember. I suppose that’s something I ought to check before carrying out my nefarious plan. If I pump the wrong sort of gas through an aperture, who knows what might happen? The problem is that, just as I am ignorant of bidding behaviour at auctions, I haven’t got a clue about gases. I know there are lots of different kinds of gas and that they act differently upon the people gathered in a room into which one or other of them is pumped through an aperture, but how I am to go about picking my gas is an absolute mystery. And so, for now, it shall remain, for there is much that trumps gas research in my daily round, and right now I feel, as I so often do, the call of the monkey, and I must pick nits out of my hair and shovel bananas down my throat and swing from larch to sycamore in my larch and sycamore enclosure, beyond the back garden, by the railway lines, where hooting freight trains thunder along the track carrying vast loads of pig iron to Pig Iron Town, where I have never been, and will never go, for it is far, far away, and built entirely from pig iron.