For a long time, I used to go to bed early. I was exhausted from long days working as a janitor in an evaporated milk factory. There are those who think that being a janitor is an easy life, little more than a matter of rattling a set of keys, sloshing a mop along a corridor floor, and glaring reproachfully at all who pass by. There may be janitors of that kidney, but I was not that kind of janitor, and never had been, neither in this nor in any of my earlier janitorships. It is a curious fact that the buildings in which I have been a janitor have all housed milk-related activities. Before being appointed to my post in the evaporated milk factory, I worked at a condensed milk canning plant, a milk of magnesia research laboratory, and a milk slops sloppage tank.

When I was younger I lacked application and was frequently reprimanded, on a carpet, as is usually the case, by my superiors. The overseer of the sloppage tank was particularly rancorous, as I recall. But by the time I fetched up at the evaporated milk factory, I took my duties seriously, excessively so, and that was why I was exhausted at the end of the day. To be precise, I was exhausted before the end of the day, hence my going to bed early.

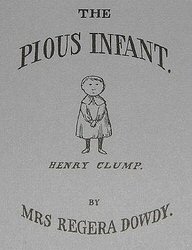

There is a pamphlet by Dobson, entitled Tips For Janitors (out of print), which helped to mend my ways. One boiling hot summer Sunday, at a loose end, I went to visit a dying janitor in a Mercy Home. His brow was beetle and his jaw was lantern, and he was slowly perishing from a malady which had set in after an attack of the bindings and which he could not shake off due to his advanced age. It was not entirely clear just how old he was, for his birth certificate had been destroyed by worms. He certainly looked unbelievably ancient when I went to see him on that boiling day. Propped up in a sort of collapsible medical chair, surrounded by dripping foliage, like General Sternwood in The Big Sleep, he had made a vain attempt to mask his decrepitude by dyeing his hair black with boot polish and by sporting the type of tee shirt worn by young Japanese trendies. Neither ploy fooled me. I knew I was looking at a janitor who had begun his career in the age of gas mantles and steam.

My visit was prompted by a plea from the Charitable Board For Janitors Close To Death, seeking volunteers to pay social calls on janitors close to death to brighten their last days. I thought myself too lugubrious to be suitable for such a good deed, but the Board’s director, an ex-flapper by the name of Mimsy Henbane, said that this particular dying janitor rejoiced in the lugubrious and funereal and bleak and that my presence would lift his spirits.

Like the Italian castrato opera singer Luigi Marchesi (1754-1829), who, irrespective of the part he was playing, insisted on making his stage entrances on horseback, wearing a helmet with white feathers several feet long, I liked to cut something of a dash when entering a Mercy Home. On this particular Sunday I was ensmothered in fine kingly raiment, complete with the pelt of a wolverine (Gulo gulo, the largest land-dwelling member of the weasel family), a burnished golden helmet Marchesi would have died for, and a bauble or two. It was stiflingly hot, of course, but my blood is ice cold, and I had achieved a temperate equilibrium as I strode majestically into the greenhouse wherein the dying janitor awaited me. I am unable to tell you his name, not because I do not know it, but because I found it completely unpronounceable. He was of Tantarabim parentage, and bore one of those impossible, and I must say foolish, names they are so fond of in that land. He was also wearing a pair of dentures which had been designed for a mouth much larger than his, so it was not only his name I failed to catch. I had brought with me, as a gift, a bag of Extra Crunchy Hard Crunchable Crackers, and it looked to me as if those gigantic teeth would be more than a match for their crunchiness. Indeed they were. For a few minutes, as the dying janitor shovelled the crackers gratefully into his gob, it was like being in a hot damp greenhouse with a snapping turtle. He crunched his way through the whole bagful so rapidly that I wondered if he was ever fed. I had not seen any staff in the Mercy Home, not even a janitor. In fact, I had not seen any other patients. There were some pigs in a sty between the greenhouse and the main building, but otherwise the place seemed deserted.

One of the things I have always liked about people from Tantarabim is that they are so easy to rub along with. After he had scoffed his crackers, the dying janitor sat there smiling weakly but, I supposed, contentedly, while I loomed above him lugubrious and funereal and bleak, just as Mimsy Henbane had suggested. I decided to stay until his smile faded, and propped myself against a pane of glass, having first twisted the dying janitor’s neck round slightly so I was still within his sight. It felt good to be doing something selfless for one who had trodden the path of janitordom before me. I pondered if this was what being a boy scout was all about. My only connection with the toggled tribe had been a single incident, in the year of the Tet Offensive, when I failed to stop a snackbar hooligan pushing a puny boy scout into a lake. I would have intervened, but I was preoccupied at the time with recalibrating a mechanism, one of my leisure pursuits in the days when I was an indolent janitor rather than the indefatigable one I became at the evaporated milk factory, when I no longer had time nor energy for leisure pursuits of any kind. Despite his puniness, the boy scout had passable swimming skills, and he managed to avoid drowning in the lake, a lake in which many had met a watery death. I knew this because their names were inscribed on a plaque affixed to a post at the edge of the lake, and I had bashed the post into the mud myself, with a hammer, one day many years before when I had nothing else to do. I used to roam the lakes and ponds and thereabouts with my hammer, looking for posts to bash into the muck. If I could not find any posts I became disconsolate and squatted on the nearest available tussock, sobbing, until it was time to wend my way home.

I had plenty of time to dwell upon my past as I leaned against the pane of glass in the hot greenhouse, for the dying janitor’s smile never wavered. It seemed that he was so pleased with the crackers and with my lugubrious presence that he had entered a state of transcendent bliss. I was determined, however, to keep to my plan of staying with him until he was no longer smiling. I knew Mimsy Henbane would approve, and in a sense it was also a way of assuaging the guilt I still felt about failing to prevent the snackbar hooligan shoving that puny boy scout into the lake. That had happened many years before, as I have indicated, but as time passed my conscience gnawed at me with ever increasing ferocity. In those days, far from going to bed early, often I never went to bed at all, instead marching up and down countryside lanes all night, incapable of sleep. I was keeping the same hours as owls, and if nothing else that fraught insomniac period helped me to extend my ornithological education. If I was a pamphleteer like Dobson, rather than a janitor, I am sure I could churn out innumerable essays on owls and other nocturnal birds. As it is, I make do by buttonholing the occasional evaporated milk factory employee and sharing my bird-learning with them, whether they like it or not. It was a pity that the dying janitor was from Tantarabim, and wearing dentures far too big for his mouth, and thus would have been unintelligible to me were he to be prodded into speech, for there was something in his demeanour which told me that he, like me, was an erudite janitor. I could not guess what his area of expertise was, of course, so I made a mental note to ask Mimsy Henbane when next I called into the Charitable Board For Janitors Close To Death HQ.

Mimsy’s journey from flapper to charitable board director was an extraordinary one. Her story has inspired poets, novelists, composers, film makers, and creative titans in just about any field you can think of, not least the designers of tee shirts worn by young Japanese trendies. Dennis Beerpint wrote a series of Cantos about her. Anthony Burgess struggled for years with a novel based on her life, but was forced to abandon it when he concluded that such a work was beyond his imaginative powers. An opera bouffe by Boof was inspired by her. Dan Brown is apparently working on a potboiler called The Mimsy Henbane Code. Before his untimely death, Rainer Werner Fassbinder planned a film about her set in a tough foreign dockyard full of tough homosexual sailors. The list goes on. Yet intriguingly, not one of the works based on her life ever addressed the root of her devotion to janitors close to death. There is always plenty about her flapperhood, and about the Antarctic expedition, the beekeeping, the shipwreck, the surgical interventions, the gladsome spring and the buffets of autumn, the postage stamp mystery, the years of crime, the gutta percha interlude, the bittersweet romances, the collapsed lung, the other collapsed lung, the delicate little fists beating hopelessly against wooden panels in the hut in the forest, the evil chickens, the gaudy boudoir, the Karen Carpenter incident, the vandalism, the scuba diving, the pitfalls, the obelisk, the gravel pathways, the euphonium band, the pint of milk, and the gruesome business in the tough foreign dockyard full of tough homosexual sailors. Yet of janitors, dying or otherwise, not one word. I know, because I’ve checked. Before I started working myself to exhaustion in the evaporated milk factory, I was able to spend some of my leisure time making a thorough study of all the Mimsy Henbane-related books and films and plays and opera bouffes and trendy Japanese tee shirts etcetera. From Beerpint to Burgess, from Boof to Brown, no creative titan deems janitors worthy of a mention. I try not to take this personally, and deny that I have poked pins into miniature wax effigies of any of those named, or of any others, such as Harrison Birtwistle and Salman Rushdie and the paperbackist Pebblehead, during spooky midnight ceremonies where I have been joined by jabbering chanting hooded bloodsoaked wild-eyed whirling drooling drugged-up maniacs. In any case, whatever lugubrious dismay I may feel towards those who have ignored my profession is more than outweighed by the fact that Mimsy Henbane herself devoted her latter years to my kind. And she did so selflessly, apart from the excessive fees she charged to those lucky enough to find a haven in one of her Mercy Homes, or in one of the greenhouses next to the pig sties in one of her Mercy Homes, and the extra charges she levied on the relicts of those janitors who, dying, died, and passed into the realm of which we know naught. So despite my hours of study, I am as clueless as the next janitor as to Mimsy’s motives. All I know is that she fully deserves my gratitude, and that is why I stood leaning against a pane of glass in that greenhouse while a dying janitor propped up in a collapsible medical chair, his hair slathered in boot polish and his dentures too big for his mouth, smiled at me for three whole days. I did it for Mimsy.

I think what wiped the smile off his face at last was that he felt pangs of hunger for more crackers. He mumbled something at me in that weird, impossible Tantarabim accent, and pointed a bony finger at the empty cracker bag he had dropped on the floor. I told him that I would go to Old Ma Purgative’s clifftop superstore, a lengthy hike away, to get another bagful. I wondered if he would still be alive when I returned. As I turned to sweep out of the greenhouse as dramatically as I had entered, in my kingly raiment, he rummaged in a little wooden cupboard next to his chair, took out the Dobson pamphlet Tips For Janitors, and pressed it into my greedily outstretched hands.

Over the next few days, as I made my slow lugubrious funereal bleak way towards the coast and the clifftop, I stopped from time to time to sprawl on bright summertime lawns and I read the out of print pamphlet from cover to cover. When I had finished it, I started again from the beginning. I was thunderstruck. In spite of my various milk-related janitorial posts, I felt I was reading about an entirely new and different calling, one of which I was profoundly ignorant. Between them, the dying janitor and Mimsy Henbane and Dobson changed my life.

Eager as I was to become a reborn janitor at the earliest opportunity, I was mindful of my promise to the dying janitor in the greenhouse next to the pig sty. I had made him so happy with that bag of Extra Crunchy Hard Crunchable Crackers, and had vowed to fetch him another bag. Torn between duty and desire, I spent a miserable morning sobbing on a tussock. Then Fortune smiled upon me, just as the dying janitor had done, by sending into my path a boy scout. As puny as the one who, years before, I had seen pushed into a lake by a snackbar hooligan, the child appeared at the side of my tussock and inquired if I had a job for him to do in exchange for a shilling. I took his coinage and sent him off towards Old Ma Purgative’s clifftop superstore, having armed him with full instructions and a map, and his shilling back to pay for the crackers. Then I turned my face towards Pointy Town and headed for the evaporated milk factory, and a new life.