After I mentioned Prudence Foxglove the other day, I was deluged with post from readers avid for more information about her. I am currently working on a biography of the unsung Victorian genius which, though potted, will also be magisterial. Meanwhile, I have managed to dig out an excerpt from her play May The Light Of Our Saviour Beam Down Upon The Cripples And Paupers Of Every Parish In The Land (1894).

[Scene : A filthy hovel steeped in gloom.]

Drunken Brute : Go and get my bludgeon so I can bludgeon you about the head in a fit of intoxicated rage.

Urchin : Lumme, guvnor, you’re as frightening a brute as ever bludgeoned a poor half-blind urchin about the head!

Drunken Brute : Yes I am, and if you don’t get my bludgeon this instant I’ll box your ears as well, you urchin you.

Urchin : Oh! Did ever a poor half-blind urchin lead so squalid and unChristian a life as I am fated to do since my parents perished in an early railway accident and I was abducted from Kindly Old Ma Dropsy’s Idyllic Cottage For Pallid Infants by the Drunken Brute?

[Urchin exits to fetch Drunken Brute’s bludgeon. Drunken Brute does some comic business with a birdcage and a set of napkins. Enter Urchin, holding a prayer book.]

Drunken Brute : What now, Urchin? That looks to me suspiciously like a prayer book.

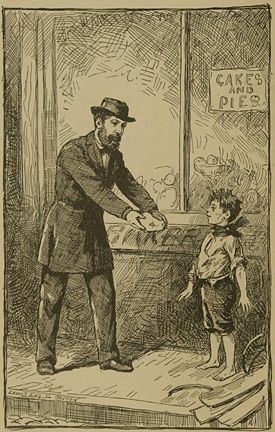

Urchin : It is a prayer book, Drunken Brute. While I was stumbling half-blind about the other part of the filthy hovel, trying to find the bludgeon, a proper posh lady dressed all in finery came and handed it to me, suggesting that I read some prayers to you.

Drunken Brute : Grrr. I’ve a good mind to give you a double boxing of the ears.

Urchin : Yes, that is quite understandable, given that you are a Drunken Brute. But perhaps the lady was right, and that if I read you some prayers you will be engulfed in the light of Our Saviour, and no longer be drunken and brutish but a reformed character of sober mien and a determination to devote your life to hard work and social advancement.

[Urchin begins to recite prayer. Drunken Brute is seized by pangs of remorse and self-loathing and collapses into his chair. Enter Prudence Foxglove.]

Prudence Foxglove : My name is Prudence Foxglove, and I am the proper posh lady who pounced upon this half-blind Urchin in the other part of the filthy hovel. And see what wonders I have wrought by bringing the word of Our Saviour into this benighted hellhole. Note, too, the daring modernism of my play, where I, the authoress, barge into the action and address you, the audience, directly. We shall leave the Urchin and the Drunken Brute bedazzled by the Lord’s light, and in Act Two we shall cast our eyes upon another scene of moral depravity and high debauch. The scene is another, filthier, hovel, where a smallpox-scarred match-girl is at the mercy of a different drunken brute, until by chance they hear a thunderous sermon from an Oxford-educated preacher, a man of stern Protestant rectitude, and their lives are transformed.