The Cow & Pins was a singularly squalid tavern, much frequented by human scum. Once, long ago, it had been a coaching inn, but the construction of an efficient canal system destroyed the coach trade, and bargees passing by aboard their barges upon the canal were a salubrious lot who drank tea from flasks and read improving literature. The Cow & Pins stood crumbling and forlorn on the lane parallel to the towpath of the canal, and soon only the crumbling and forlorn, the indigent and misbegotten, the violent and the psychopathic ever set foot upon its rotten sawdust-covered floor.

One psychopath who became a tavern regular, the ferocious Babinsky, took over as the landlord after chopping up the existing incumbent with an axe and feeding him to the pigs. The pigs, who lived happily in a pig sty a little way down the lane from the tavern, did not of course know their swill that day contained the ground-up remains of their pal from the Cow & Pins, who used to commune with them, in a hearty man-to-pig way, whenever he got the chance. With Babinsky at the helm, things changed. Babinsky hated pigs, and after that first feeding, he shunned the sty, some said in fear that the spectre of the man he had chopped up and then ground up and then stirred in with the pigswill lay in wait for him there, to wreak revenge from the realm of death. It is more likely, however, that Babinsky was too busy being mad and bad and dangerous in the tavern where he now held sway.

He tore down from the walls the showbiz memorabilia that had most recently adorned them. Gone were the photographs of the previous landlord arm in arm with Rolf Harris and Val Doonican and Edith Sitwell. Gone were the autographed portraits of Ken Hom and Tammy Wynette. Gone were the posters advertising pantos with Keith Chegwin as Buttons and George Galloway as Pol Pot. In their place, Babinsky pinned up his weird, hand-written screeds, pages and pages ripped from the exercise books which he filled with gibberish. Out went the barrels of ale and the bottles of champagne and liqueurs and rare expensive brandies, out went the soft drinks and the mineral waters, and in their place was installed a single vast trough, into which was poured, and out of which was ladled into dented tin beakers, disgusting bilge made of god knows what. Its taste was foul, but it was cheap, and just a beakerful or two sufficed to ravage the drinker’s brain to zombiedom. Babinsky himself allowed no other fluid into his body, which probably accounted for what one might charitably call his eccentricities.

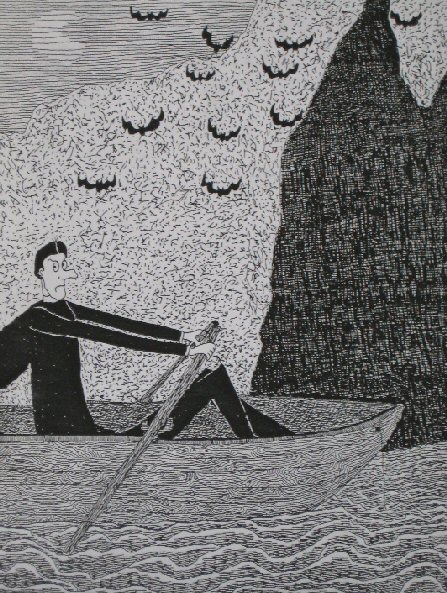

Under his predecessor, there had been a jukebox in the Cow & Pins, well-stocked with the gems of prog rock. Babinsky smashed it up with his axe and sharpened the edges of the discs inside so he could use them as missiles, slicing through the air to hit and sever a jugular or other important vein through which the blood relentlessly pumps. Then he dug a deep, deep pit and fed wires down it, wires at the end of which were microphones that picked up the constant agonised howling and screaming of sinners being tormented for eternity in the pits of Hell, amplified and blaring at ear-splitting volume from speakers placed all around the tavern. It was a rough and raucous place, perilous for the weedy toper who might once have sat in the snug watching coaches rattle by. The snug itself had been demolished by Babinsky and the space it had occupied was now a charnel-ground stacked with the bleached bones of those he slew, when he was in the mood for slaying, which was most days. Sometimes the villain would pole-vault across the canal, like Spring-Heeled Jack, for the sole purpose of setting upon a poor innocent orphan or cripple plucking flowers for a nosegay from the canalside shrub beds. Babinsky carried out his killings with impunity, for a type of amnesia stalked the land, and even the police officers blundered about in a hypnagogic daze.

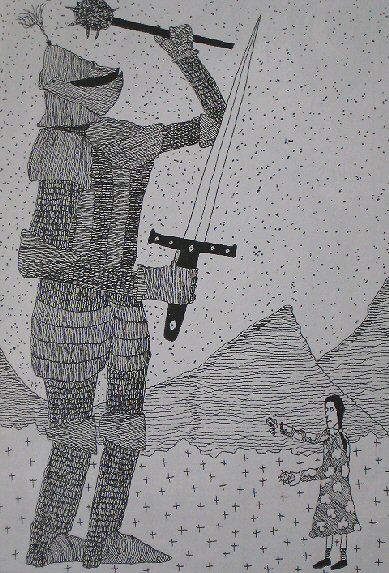

The one law that was rigorously enforced in this land of efficient canals was that which regulated the licensing hours of taverns. Even Babinsky, yes, Babinsky himself, was terrified of the Tavern Time Trio, three brutes who patrolled on horseback to ensure that every tavern was locked and bolted and dark and silent as the clocks struck the witching hour. Their horses were as brutish as the trio themselves, gigantic fierce beasts with repulsive fetlocks and manes matted with muck, whose merest whinny was a thousand times more hideous than the infernal muzak of the Cow & Pins. Freeman, Hardy, and Willis, the horses were called, but nobody knew the names of their riders, for nobody ever dared to ask, just as no taverner ever dared to let his tavern stay open for one second past closing time. Nobody could even remember when the law had been broken, so nobody knew what punishment would be meted out by the Tavern Time Trio. The sheer size of the horses, and their rank stink, and the thunder of their hooves as they galloped from tavern to tavern, and the brutishness of the trio themselves, in their gold lamé tuxedos and snow white spats, and the piercing whistles they blew as they rode, and the official documents poking out of their pockets, these things were enough to cow each and every tavern keeper, Babinsky included.

So it was that in spite of the clamour and uproar of the Cow & Pins, easily the most exciting part of the day was chucking-out time. Human scum, their brains and bodies jangled by whatever it was they’d been gulping down from Babinsky’s trough, would be startled by the sudden cessation of the amplified agonies of the netherworld, their ears assailed instead by Babinsky’s hooter. Those of you familiar with this contraption will know that it was the most powerful hooter that ever existed on earth, or on any other planet in any other universe, a hooter par excellence, the ne plus ultra of hooters, a hooter the like of which we shall never hear again, for which, in truth, we should be thankful. Babinsky parped his hooter just once, to signal that the Cow & Pins was closing for the night, and once was all that was needed. To imagine hearing that hooter hoot twice in succession is more than the mind can bear, whether the mind is sane and sober or blasted to fuddlement by dented tin beakerfuls of disgusting bilge. Not that the sane or the sober would be found among the human wreckage who, hearing the hooter, drained the last drops of bilge from their beakers and tossed the beakers into the trough. Then out of the tavern they tumbled, a jumble of chaos, many of them toppling into the canal, others falling and lying flat on their backs where they fell, in the mud, where they would remain insensible until the Cow & Pins opened its doors the next morning.

And inside the tavern, Babinsky, who never slept, filled with bilge all the beakers that had been tossed into the trough and lined them up on the counter. He put on his superloud Bang & Bangbangbang quadrophonic headphones and switched his subterranean microphones back on. As he listened to the shrieks of the sinful, he worked his way through the line of beakers one after another, and when he was done he wrote one of his weird screeds and pinned it to the wall, and then he lumbered out into the dead of night in search of something to slaughter.

The Cow & Pins was, of course, Dobson’s preferred tavern, but by the time the out of print pamphleteer came to patronise it Babinsky was long dead, and it was once again the kind of place where a weedy toper could sit in the snug and scribble a pamphlet. Not that Dobson was weedy, exactly. He occasionally got into fights, and acquitted himself with aplomb. As for Babinsky’s hooter, when the new landlord took over the tavern he had it dismantled by specialists from a hooter dismantling squadron. To be on the safe side, they buried the parts separately, in deep lead-lined wells, unmarked, and scattered across six continents. Foolishly, though, the captain of the squadron made a map pinpointing the locations, to keep as a souvenir, and last week it was reported in The Daily Hooter that the map had been stolen. Yes, friends, it is a horrible possibility that even now, somewhere out there, a madcap genius is hard at work putting Babinsky’s hooter back in one piece! You may well say “Eek!†I know I did.