Given its title, one could be forgiven for thinking that Confessions Of A Door-To-Door Monkey Salesman is a 1970s British sex comedy film starring Robin Askwith. In fact, it is a Bildungsroman of fierce intensity. Annoyingly, its author has chosen to remain anonymous. The book begins thus:

I was born in a cornfield. The first sound I heard was the shrieking of crows. My mother put me in a burlap sack and dropped me down a well and went on with her rustic drudgery. At the bottom of the well ran an underground stream. I was carried along for miles until the stream surfaced alongside a dilapidated pig farm. The pig farmer’s wife was washing potatoes in the stream as I came by in my sack. Never one to waste a good piece of burlap, she plucked the sack from the stream and found me inside it. I was gurgling.

We might think this far-fetched, were it not that there are many true tales of babies, and hamsters, surviving journeys fraught with much more peril. The note about the crows is intriguing, reminding us of the old saying, I think from Filthshire, “a child born to the cawing of crows will have too few fingers and too many toes”. And what do we learn on page 26?

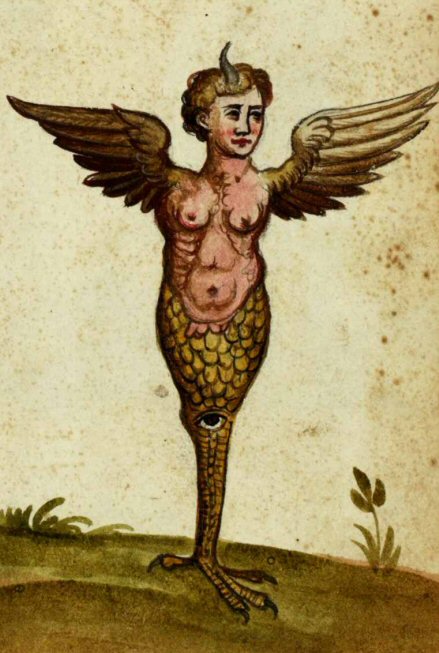

I remember quite clearly the night my adoptive pig farming mother read to me, as a bedtime story, passages from a book describing freakish human anomalies. There was a two-headed boy and a girl with eight kidneys, a giant with yellow lips and a woman with upside-down ears. As she closed the book, at the end of a chapter on people with lobster claws, and I was falling into sleep, she whispered “and you, my cherished tiny one, are a freakish anomaly, with your two thumbs, seven fingers, and eleven toes”. I sprang up, wide awake. Until then, I had not noticed my irregularity. Of course, I had counted my own fingers and toes many times, as a way of passing the time on rain-soaked pig farm afternoons. But being very short-sighted, I had never looked at other people’s hands and feet with any acuity.

Shortly after this realisation, the boy is bought his first pair of spectacles. The prescription is flawed, for the corrective lenses are obtained from an optic rascal, and the world remains blurry and distorted. Our hero can still not see well enough to count the toes and fingers of others unless they shove their hands or feet right in his face, and he is too diffident to ask. But he gains inner strength from his status as an anomaly.

I read and reread my mother’s freak book, poring over the details, and fantasising that I had more enigmatic qualities than were outwardly apparent. For example, because I was mad for eating nuts, any nuts I could get my hands on, I became convinced that I had the brain of a squirrel. I spent long hours in the woods near the pig farm talking to squirrels in a language I thought they might understand. I trained myself to quiver and tremble and dart about as if I had the high metabolic rate of a squirrel. This behaviour continued until my thirty-first birthday.

No longer a child, but with little experience of life away from the dilapidated pig farm, the author of the Confessions reports abruptly the cataclysmic change that occurred on that birthday.

My adoptive parents perished in the Munich air disaster. They had won a raffle to attend the second leg of the European Cup quarter-final between Manchester United and Red Star Belgrade. It was the first time they had left me in sole charge of the pig farm. When the postie came up the lane with the telegram telling me the terrible news, in my convulsive grief I suddenly realised that I did not have the brain of a squirrel, and never had had, and that life held for me greater prospects than mucking about in the woods babbling gibberish and gnawing nuts. I was now the master of a dilapidated pig farm.

Was he its master? Or did the farm master him, in the shape of the pigs? There were very few pigs left on the farm, no more than half-a-sty’s worth, and they were belligerent, cunning, and rancorous. They were, in a way, freakish anomalies themselves, very different from the peaceable intelligent pigs we are so fond of. For years, the deceased pig farmer and his wife had been adding a secret ingredient to their bran mash, on the advice of a plausible pigfeed rascal, a crony of the equally plausible optic rascal who had supplied our hero’s defective spectacles. Quite what the pigs had been ingesting for decades is unclear, but it had wrought psychic pig havoc. They were more than a match for a myopic innocent who was trying to adjust to his new life. Within weeks, charming bucolic dilapidation became utter ruin.

The last straw was a tempest which flattened the barn and the pigsty and sheds and huts and outbuildings and even the farmhouse itself. The local newspaper described it as “an unusual weather event”. In the teeth of the storm, the pigs ran amok, and vanished up in the hills. I sat on the ottoman surrounded by collapse. Fate decreed that a pig farmer’s life was not for me. I had a sudden urge to regress, to return to the woods and commune with squirrels, but I fought it. My spectacles had been smashed during all the chaos, and I determined that, as soon as the wind died down and there was daylight, I would seek out the optic rascal to get a new pair.

Our credulity is strained somewhat when we are told that the only item to survive the devastation of the tempest, apart from the ottoman upon which he is sitting, is the narrator’s dead adoptive pig farming parents’ hand-compiled Directory Of Countryside Rascals, a ring-binder jam-packed with details of hundreds of rustic chancers, including full contact details, mugshots, handwriting samples, maps, and of course their areas of persuasive rascality, whether it be optics or pigfeed, and much else besides. Armed with such exhaustive information, even our short-sighted hero could not fail to track down the rascal he sought. Or could he?

I was two days distant from the rubble that had been my home when, sheltering under a sycamore from a sudden shower, I peered for what felt like the umpteenth time at the sheet I had taken from the ring-binder. My intention was to check that I was following the map accurately, and had remembered to veer left after crossing Sawdust Bridge. Now, holding the page the right way up, I suddenly discovered that I had mistakenly brought with me the information sheet not for the optic rascal, but for quite another rascal entirely. I supposed, back at the obliterated pig farm, I must have been befuddled. I pondered whether I could cope without a new pair of spectacles. Before the interruption of the shower, it had been a sunny day, and I was in high spirits. After all, here I was on the open road, a free agent, no longer tied down by pig farm responsibility. I could do as I pleased. And I was coping well enough blundering about in a blur. I held the paper up close so I could read my dead adoptive mother’s scrawl. No doubt about it, I had the wrong sheet. It was headed “Monkey Rascal”, not “Optic Rascal”. I could not recall a time when a monkey rascal had ever called at the pig farm, but my adoptive parents were resourceful folk, and they gathered details of sundry rascals of whom they had no immediate need. The monkey rascal was one such, his information sheet compiled with care just in case his services might one day be required. As the rain spattered down around me, I wondered what those services were.

He finds out soon enough. It takes just three more days trudging, faithfully following the map, for our hero to arrive at a monkey compound on the outskirts of a macabre village. Wisely, he avoids going through the village itself, and bypasses it, taking a detour through a long, muddy, puddle-pitted but not disagreeable ditch. The gate of the compound is unlocked. Though he can barely see in front of him, he hears the whistle of a steam kettle and, shortly afterwards, the telltale glug and clatter of cocoa preparation. Heading for the sound, he finds himself in the monkey compound canteen, where the monkey rascal is holding court, sipping cocoa and surrounded by monkeys. He is in for a surprise.

“You must be the pig farmers’ adopted son,” he said, as soon as I blundered through the canteen door, “I’ve been waiting for you”.

He is given a cup of cocoa, and everything is explained.

“When I heard your parents had been killed in the Munich air disaster I knew it was time for me to fulfil the pledge I made to them on the day you were hoisted out of the stream,” he continued, “I was there. I was about to sell the pig farmer and his wife a monkey when they found you instead. I must have looked peevish at the loss of a sale, because they came over very guilt-ridden at the thought of sending me away empty-handed. So they said that, so long as I was happy to keep hold of the monkey they had planned to buy, they would rent it instead. They paid me on the dot every month from that day until that tragic day in Munich. And as part of the monkey rental, they made me promise that, should anything ever happen to them, I would take you under my wing and look after you until the day one of us died. That’s why, when you were asleep in a hedge a few nights ago, one of my trained monkeys took the optic rascal’s details out of your satchel and put mine in there instead. So here you are.”

He sounds like a splendid fellow, but we must remember that he is as rascally a countryside rascal as all the other rascals in the Directory. It rapidly becomes apparent that he has concocted a plan. Yes, he will fulfil his pledge to care for our hero, but he expects something in return, and it is no small thing.

“That monkey rental money has kept my head above water these past thirty years,” he went on, pausing now and then to slurp his cocoa, “I sorely miss it, and these old bones of mine aren’t getting any younger. I am mindful, too, that the woods hereabouts are fairly riddled with squirrels, and I don’t want you tempted to go down there and rekindle the squirrel-brain nonsense your adoptive parents told me all about in the long, tear-stained letters they sent me with their monkey rent cheques. So I propose that in return for your cocoa and soup and a mattress in the monkey compound, you are to act as my very own indentured door-to-door monkey salesman, starting at dawn and clocking off after nightfall, every day except St Abodwo’s Day, he being the patron saint of monkeys, according to some. I hope you will be pleasantly surprised at the number of householders willing to purchase a monkey there and then from a myopic stranger who bangs on their door out of the blue. Now finish your cocoa and you can get to work.”

And so begins a period of more than twenty years during which our hero pounds the streets of villages and hamlets and towns and cities, a string of monkeys in tow, banging on the doors of people from all walks of life, high and low, professional and prole, refining his sales patter, which grows in expertise the more surely as his sight fails, until towards the end, it is he who is led by the monkeys, on a length of string, and then one day…

One day it happened there was a mix up, and a kindly retired vicar who had taken a shine to Martin the howler monkey handed his cash to Martin and took me into his vicarage by mistake. I have been here, happily, ever since, fed on cornflakes and brazil nuts, and living in the overheated conservatory among dripping plants with fat bulging leaves. It is here I have written my Confessions. From time to time I think of the monkey rascal, and how distraught he must have been when I did not come home that day. He must feel he has broken the pledge he made to my adoptive pig farming parents more than half a century ago, albeit through no fault of his own. I weep for him sometimes, thinking of him in his canteen, perhaps with Martin at his side, howling. But then I snuffle and dry my eyes, and remember that he is a countryside rascal, and like all rascals he will have other irons in the fire. I wave to the kindly retired vicar through the conservatory window, and I chew another brazil nut and I pour another bowl of cornflakes down my throat.