You will be perplexed, or perhaps even sick with worry, at the unaccustomed lack of postages over the past few days. Has Hooting Yard been ravaged by some kind of toxic gas? Has Mr Key fallen down a mineshaft? Readers, fear not. All is well, but I have been terribly, terribly distracted, and in the best possible way.

On Saturday, as is my habit, I sat down at my escritoire, or its computer age equivalent, before dawn. I wrote:

There is a tavern in the town.

The tavern was the Cow & Pins, the town was Pointy Town. I was going to embark upon a quite breathtaking architectural survey of the tavern, its beams and rafters, its cornices and lintels, but before I crafted the second sentence my attention was caught by the singing of a siskin outside my window. According to the Royal Society For The Protection Of Birds, the siskin is an attractive little finch, small and lively. Obviously I was keen not simply to listen to the bird, but to commune with it, in what might be termed a Frank Key-bird-mind-meld. So I jumped up creakily from my chair, slipped on a pair of trendy footwear items, and headed out, making for the tree where I thought the siskin was perched, singing. Alas, I stepped in a patch of filth, and was disconcerted. Rummaging in the pockets of my windcheater to see if I had upon my person a rag suitable for wiping the filth from my footwear, I chanced upon a forgotten scrap of paper on which I had once copied out a Spirograph™ drawing, the one devised by the mentalist Gaston Freakorb. Yes, that one, the drawing that plunges the viewer into a fugue state. I made the mistake of uncrumpling the paper and peering at the drawing for three seconds. Thus did my Saturday morning become unmoored from reason, from common sense, indeed from memory. The architectural glories of the Cow & Pins were forgotten, as was the attractive little finch singing its heart out on a sycamore branch.

When I snapped out of the so-called Freakorb Mind Miasma, it was midday on Sunday and I was standing in a queue. To my distress I noticed that both of my trendy footwear items were now covered in filth. Luckily, there was a Regency bootscraper right next to me, so I scraped and scraped. By God, it was fun. I thoroughly recommend the scraping of filth off one’s footwear on a Regency bootscraper, particularly when one’s footwear is as trendy as mine.

There was no sign of the scrap of paper bearing the Spirograph™ drawing, so I was fairly sure I could keep my wits about me. I wondered what I was queuing for. Glancing up and down the line, I noticed that an alarming number of my fellow queuers were wearing cummerbunds. Was I about to enter a Spandau Ballet revival meeting? Then I recalled having read somewhere that the cummerbund was part of the uniform designed for “new modern technicians” to which the Prime Minister would refer in his upcoming conference speech. But I am a scribbler, not a technician, new and modern or otherwise. I had no business here, surely.

It turned out to be a complete coincidence. I learned that some of the cummerbundiasts were indeed new modern technicians-to-be, some were raddled old New Romantics, and some simply sported the cummerbund as, in their own witless words, a “lifestyle choice”. To find all this out, I had to interrogate each person individually, making notes with my pneumatic notemaking contraption, and in so doing I lost my place in the queue. Rejoining it, I found myself standing behind a twinkly elfin chap dressed all in green, though minus a cummerbund. Suddenly he spun around to face me, and he cackled, and shouted in a weird reedy voice.

“Guess my name and I’ll tell you / What you’re doing in this queue. / If you guess amiss three times / I will cease to talk in rhymes. / I will scream and shriek and howl / And you’ll be turned into an owl.”

Then he cackled again, daring me to challenge him. I did a stage yawn. I think I did it rather well.

“I suspect,” I said, “Your name is Rumpelstiltskin. Am I correct?”

The little chap shrieked, then, but it was not a shriek of triumph. Far from it. I had rumbled him and his feeble fairytale poltroonery, and his shriek was one of becrushment. Just before he scampered away with smoke billowing out of his pointy ears, he told me what I was queuing for. I was delighted to discover that I was in line for an auction of rare Bobnit Tivol mezzotints. I was even more delighted when, fumbling in my pockets, I found a wallet crammed with banknotes. It had not been there when I left the house to commune with the singing siskin, so it must have come into my possession during my fugue state. I made a mental note to write a thank you letter to Gaston Freakorb when I got home, and slowly made my way towards the front.

I was, of course, aware of the set of mezzotints of fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol made by the noted mezzotintist Rex Tint at the very beginning of his career. Commissioned by the fictional athlete’s coach Old Halob, paid for with the proceeds from an orchard-planting scam, the twenty-six mezzotints were no sooner completed than they were scattered to the four winds, and had never since been gathered together. Nor were they now, alas, but it was quite something to have three of them up for sale, along with an even rarer mezzotint purporting to be of Old Halob himself. I had so much cash in my fugue-wallet that I easily outbid everyone, even the creepy agents deployed by Rex Tint’s sworn enemy, he who is the man they call “Sting”. I admit I was rather dismayed to be handed the mezzotints rolled up into a cheap cardboard tube, but it has to be said it was a fairly slovenly auction house, as auction houses go.

Anyway, when I got home I flattened each of the mezzotints out on my kitchenette table, and spent hours upon hours poring over them, while outside the siskin, that attractive little finch, sang and sang. That is why I have not had time to post anything. I have been transfixed by my mezzotints. So let me show them to you, in the form of rough copies I have made, just in case the pebbles weighing them down are dislodged and they are scattered once again, to the four winds.

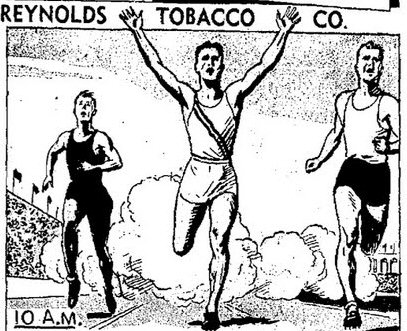

Here we see fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol as a Christ-like figure, flanked by a couple of thieves, just as in the crucifixion. It is thought the mezzotintist Rex Tint made some sort of arrangement with his local prison to have a pair of miscreants pose for him, hence the startling pelfeusement of the portraiture. As for fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol, he’s just great, isn’t he?

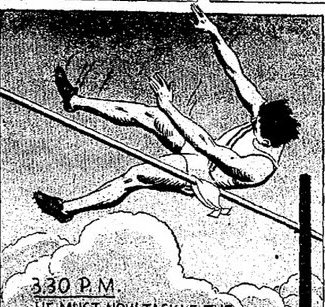

In this mezzotint, Rex Tint has captured the one occasion when the fictional athlete was disqualified for cheating. It shows him winning the fourth heat of the qualifiers for the 1926 Scroonhoonpooge Farmyard Polevaulting Tin Cup, where, notoriously, he vaulted without using a pole.

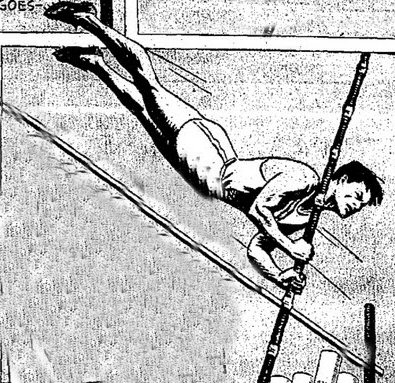

Rex Tint uses his vivid imagination to show how things might have been, depicting the same vault but pretending fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol had used his pole. Old Halob tried to use this mezzotint as evidence when seeking to overturn his protégé’s disqualification, a ruse which failed and led to the cantankerous coach being locked up in the eerie barn at Scroonhoonpooge farmyard for half an hour. He was never the same man thereafter.

It is claimed that this mezzotint shows Old Halob himself, pausing on the way to his favourite tobacconist.