Oi, FK!, writes Tim Thurn in his usual artless manner, I am appalled at the latest evidence of your slipshod treatment of your loyal readers. I very much welcomed the Daily Bird Challenge instituted here on Monday, and I was even preparing to acknowledge that perhaps you do know a little bit about ornithological matters and are not a hopeless avian dumbkopf, as I have always suspected.

I threw myself heart and soul into the first of your challenges, removing my binoculars from the satchel wherein they have been gathering dust since the last century and stalking up and down and around my bailiwick hoping to spot a bluebird and a robin and a starling and a grackle. I took a bag of reconstituted meat paste sandwiches and a flask of piping hot tea, because I was in this for the long haul, and could see myself being stranded on a hillside come dusk. I even had a picnic blanket thrown over my shoulder, just in case. I spent the whole bloody day in the open air, in spite of the weather, though I would have liked nothing better than to be curled up on a rug in front of a roaring fire, like a well-kept dog.

Now, perhaps it is my own fault that I failed to check the noticeboard outside the civic hall, and thus was unaware that Monday had been designated And No Birds Sing Day by the authorities, in honour of some ailing palely loitering knight-at-arms of yesteryear. Clearly, the birds, their tweeting and chirruping forbad, voted with their wings and scarpered to a different neighbourhood for the day. That is why I failed to spot any birds at all, let alone the ones designated in your challenge. But I repeat, I put a great deal of effort into it, at some risk to my holistic wellbeing, for I suffered much, much!, until I eventually threw in the towel, towards midnight, and staggered home in a state of mental and corporeal exhaustion. The straw that broke the camel’s back was when I was impugned by a peasant while trudging around the lake, upon which even the sedge was wither’d.

I slept in fits and starts, having hideous dreams about eggs and monkeys, but when I rose on Tuesday and plunged my head into a bucket of icy water, I consoled myself that the day would bring a new bird challenge. I resolved to be better prepared, and before dawn I took a little hike over to the civic hall to check the noticeboard for any further bird-related announcements. There were none, but to be on the safe side I popped in to Old Pa Kropotkin’s Bleach ‘n’ Fags ‘n’ Periodicals Kiosk to pick up the local newspaper. Back home before cock-crow, I read This Particular Bailiwick’s Daily Intelligencer front to back, line by line, twice, over a breakfast of goat milk slops. I did not want a repeat of yesterday, with its crushing humiliations, so I meant to be absolutely sure I was apprised of all pertinent local ornithological goings-on before I took the daily Hooting Yard bird challenge.

There was much to take in, for the Intelligencer was packed with special reports from its tiptop bird reporter, young Dagobert Stalin, whom I had had the pleasure of meeting a couple of times as he scampered around the bailiwick with his reporter’s pad and propelling pencil. There on page one was his “take” on the success (or otherwise) of And No Birds Sing Day. Apparently a crone on Rolf Harris Avenue had failed to muffle her sandpiper, while an avant-gardist at the Conservatoire had insisted on rehearsing his Passacaglia For Three Electronically Enhanced Buffleheads. Both crone and composer were to be shot at dawn, I learned, and in fact, in the distance, I heard the firing squad. Turning to page two, Stalin had a piece about owls, from which I could wring no sense, since he had written it aping the style of Terry Eagleton. The next few pages were taken up with the dismal and the mundane. I was looking for announcements and pronouncements of a birdy hue, and eventually found some on the inside back page. Today, Tuesday, I learned, there was to be an ostrich display in the park, the unveiling of a tin blue-footed booby statue in the market square, some flummery with birdseed and tea-strainers at the Opera House Annexe, and, according to Dagobert Stalin, the expected appearance, in the sky, of an enormous flock of migrating swallows, a flock so enormous it would blot out the sun. On the back page there was a small item about a siskin, an attractive little finch, caged, and to be presented as a prize to the orphanage’s Orphan Of The Month. Spooning the last of my goat milk slops down my gullet, I was well pleased and confident that I was as prepared as ever I could be for today’s bird challenge.

Inside the technohut, I depressed the computer knob which began the process of “powering up” my Macrohard Vista operating system. In just a few hours now, I would be plugged in to the information superhighway of which Mr Blair had spoken with such enthusiasm. It seemed so long ago, that bright new dawn when things could only get better. I could barely remember whether it was before or after Peter Mandelson sported a dapper moustache, and which guide dog accompanied David Blunkett at the time. Thinking these thoughts, with time to kill, and savouring the goaty residue coating my tongue, I strode manfully over to the town gymnasium to throw medicine balls around to no apparent purpose and to spend a while on the simulated bobsleigh machine. At the corner, as luck would have it, I bumped into young Dagobert Stalin, but he was in a frantic hurry, rushing to some newsworthy incident, of which I would no doubt read in tomorrow’s paper.

PT done and puffed out, not unlike a magic dragon, I returned to the hut and was pleased to see steam hissing from the i-ears of the computer, a sure sign that only a few minutes remained before its “booting up” would be complete. I was already booted, of course, and, in anticipation of the challenge to come, had changed into my dappled dun suburban rambling fatigues. I sat at the console and waited for the Brian Eno Parp. As soon as it parped, I logged in to what our Belgian chums call het internet and steered my way to Hooting Yard.

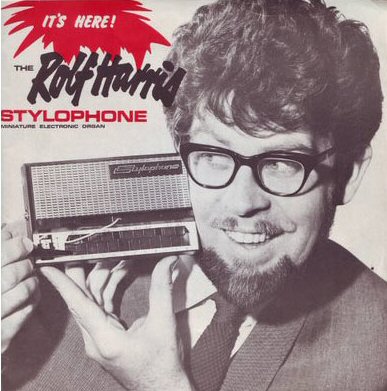

What did I find? A picture of Rolf Harris, never unwelcome, but of no ornithological interest. Some drivel about Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss. The mention, twice, of “certain swooping birds of the air” momentarily sparked my interest, but no challenge was laid down to the reader, so I spat into my spittoon and moved on. Nineteenth century twaddle about mesmerism, followed by blather about soup. And? And? Nothing else. No Daily Bird Challenge.

This, Key, is what I mean when I rebuke you for being slipshod and abusing the devotion, sometimes fanatical, of your readers. It has become quite clear that you know not a jot about ornithology, but I am now forced to ask if you actually understand what the word “daily” means. The newspaper I pored over with beetle-browed concentration is This Particular Bailiwick’s Daily Intelligencer. Has the significance of that title occurred to you? It signals, even to a halfwit, that the paper comes out every day. Not just now and then. Not just on rainy days. Not just when young Dagobert Stalin, its tiptop bird reporter, can be bothered to clamber out of bed a-morning and arm himself with his reporter’s pad and propelling pencil and charge with the vigour of youth through the streets and fields keeping his eyes peeled for all manner of birdy activity. No, the paper appears, on Old Pa Kropotkin’s kiosk counter and on other counters, and on shelves and racks and turny display carousels, every single day of the year, except of course for important festive holidays when everything shuts down. I speak of days such as the anniversary of the Hindenburg disaster and Yoko Ono’s birthday. But otherwise, “daily” means “every day”. How in the name of the Prince Elector of Tantarabim can you claim as much for your bird challenge? It appeared once, and then the very next day it was gone, pfft!, vanished in the haze, like that conjuring trick with the magnet and the whisk and the attractive little caged siskin which I have been practising in my leisure hours.

I am surely not the only reader to find myself sorely tested by your cavalier ways, Mr Key. Why don’t you just come clean and admit that what little you know of birds could be written, in very big bold block capitals, on a pinhead, and the head of a tiny, tiny pin at that, not one of the bigger ones you find in shops for the larger pin and pointy thing user? Were you to confess as much, believe me, you would feel refreshed, as if washed in the blood of the lamb and wrapped in a towel of unimaginable fluffiness. If I were not due back at the gymnasium in a few minutes to put all the medicine balls back in their cupboards and to tweak and grease the simulated bobsleigh machine in readiness for the orphans’ simulated bobsleigh cup tie needle match tomorrow, I would happily draft a mea culpa for you, with vivid and sprightly wording you could be proud of. As it is, I and the rest of your despicably ill-treated readers will have no choice but to entrust you to do the decent thing.

Yours, more in sorrow than in anger, well, in truth, boiling with rage and minded to strangle a few hens to assuage my fury, Tim Thurn.

Mr Key would like it to be known, and not just known but shouted from atop tors and promontories, that he has no intention of writing any such confession of avian ignorance, now or at any time in the future, for he knows all there is to know about birds, from the Arabian babbler to the barn owl to the carrion crow to the dotterel to the Egyptian goose to the fulmar to the Goliath heron to the hoopoe to the indigo bunting to the jackdaw to the kittiwake to the little stint to the moorhen to the nightjar to the Oriental pratincole to the pin-tailed snipe to Quetzalcoatl, albeit a mythical serpent, but with feathers, with feathers, like a bird, to the ruddy shelduck to the sombre tit to the twite to the upland sandpiper to the veery to the whimbrel to the yellow-bellied sapsucker, yea, unto Zino’s petrel. Shame on you, Tim Thurn, shame on you! Next you will be telling me there is a bird beginning with X. There is not.