Today’s essay is a guest postage by BlackberryJuniper & Sherbet. When she told me she was planning to write On The Magnificence Of Peter Wyngarde, I realised this was a perfect topic for the Hooting Yard daily essays, but one which I was not qualified to address. This is an abridged version. You can read the full mad frothing at the mouth here.

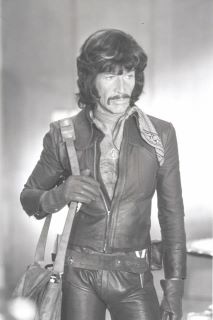

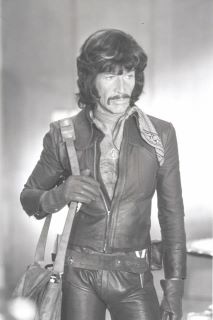

Have a proper look at this exhibition of early seventies utter cool, and ask – who else can carry off leather pants in this way, and a moustache, and still be astonishingly intelligent and a slightly louche action hero also?

Now, I don’t mean for a moment to be merely dribbling over one of the most gorgeous actors still alive, in a horrible sexist way. I would sincerely love to meet Peter Wyngarde and have, umm, a croissant and some orange juice with him. I would love to chat and hear stories, and just listen to the marvellous George Sanders-esque voice. I truly think the man is one of the best actors we had, before some people got hot under the collar that despite always being a ladies’ man on TV, he got arrested for some business in a toilet in Gloucester with a truck driver in 1975. (The fact that his acting colleagues often called him ‘Petunia Winegum’ as a nickname testifies to the fact that being gay wasn’t a secret among people that knew him.) Since some people weren’t ready to handle the fact that the leather trousers were active in a way they hadn’t expected, his career suffered and got halted, really. What a total bloody shame! After all those sudden 1965-67-ish appearances in staples like The Avengers, The Saint, Armchair Theatre and The Prisoner, he drifted away. Just when it was all getting going.

Now, I haven’t looked into his career in any great detail, but if he’s in something I will watch it and keep it, as he never disappoints. Such presence, such confidence. I think this used to be called brio, as in – full of energy, life and enthusiasm. And class!

My earliest Peter Wyngarde memory is a masked Peter Wyngarde, as seen in Flash Gordon (1980). Which is one of the most perfect films ever made and I wouldn’t change a hair on its head whatsoever. Why so many people dislike this film so strongly is completely beyond me. What does it matter that the actor playing Flash Gordon apparently wasn’t acting very well? I thought he did fine, they didn’t paint him as a great brain – more as a character that had heart and energy; Sam Jones did fine with that brief, I reckon. What is there to dislike about the intense, insane over-colourisation: all that GOLD, and green, and red, and orange, and shininess everywhere?? Every time I watch it I am cheered up even if the sound is down! And if the sound is up, I get to hear Ornella Muti purring and sulking, Melody Anderson cheerleading and offering Suzanne Danielle the elixir that will make a night with the Emperor Ming doable (his sexual weirdness is hinted at several times, in a rather titillating way). And then there’s Emperor Ming himself, Max von Sydow, who despite his marvellous face makeup and great costuming, still manages to attract my attention by doing more evil hand-rubbing acting than anyone I have since seen in a film; more pregnant pauses before evil sneering. And of course, Brian Blessed yelling ‘DIVE!’. And the Queen soundtrack… the Love Capsule music is always overlooked and so sensually splendid I bought the whole soundtrack just for that, those few seconds…

And then, there’s the voice that I didn’t really identify properly until about three years ago. I have watched this wonderful soul-edifying frothy film of excellence about a thousand times, and yet, oddly, I had never really connected the cast list. I think I forgot George Sanders was dead, and imagined the voice of Klytus, Ming’s state torturer, was him, somehow. Then one day, I really listened and realised that (a) George Sanders had indeed been dead since 1972, and Flash Gordon was a 1980 film, and (b) that voice didn’t really sound like George Sanders at all – it was too deep and way more nuanced. So the fact I had been dribbling all this time over a masked person I had only just realised starred in one of my other favourite films was …well, I have a quiet life, I was very excited.

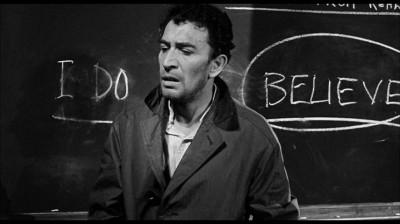

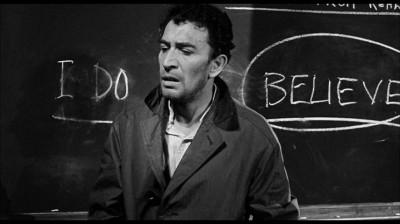

The other favourite film was Night of the Eagle (1962). I can’t recommend this film highly enough. Spoiler alert!! It is about a scientific and sceptical professor who is doing very well in his rising career at a small university, but is unaware this is because his wife is working protective voodoo on his behalf; as she is actually battling the forces of greedy and voracious bad magic, summoned up by the Head Teacher, Margaret Johnston. At the end she summons a huge thoughtform eagle to get rid of Wyngarde’s character, but a wonderful contrivance with an old eight track player sends it against her instead, hence the title. End of Spoiler. This is the face of Peter Wyngarde I had been very familiar with for years –

Which doesn’t look at all like the first picture, does it? I had no idea it was the same person. It’s a genuinely scary film, with some good jumpy moments. Go and feast your eyes on the acting talent that is this man, on YouTube – the whole film is up there.

Another thing I had been wanting to see for ages was the Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense (1984). I started to watch them in the day, and an episode came on with That Voice! Putting down my toast and honey, I see that Peter Wyngarde is there, complete with wonderful moustache, and robed as a devil-worshipping priest. I think it’s slightly likely that he was a little bored by this acting assignment, as I have rarely seen him loucher in something; then again, it’s a very slight story. There’s a funny scene near the end of the episode (‘And the Wall Came Tumbling Down’) where Wyngarde’s character is supposed to be dead on the floor. The scene’s focus is away from him, to the actors still alive, upright and talking, gesturing. Of course, I was just staring at Peter Wyngarde on the floor, loving those cheekbones and eyebrows. I don’t know how long the scene may have taken to film, but he gets bored being on the floor and makes a face, licking his lips and the tip of his moustache very obviously. It made me laugh out loud.

In speaking of his TV and film stuff, I am leaving out his notorious record, recently re-released on CD – When Sex Leers Its Inquisitive Head. I’m not even going to attempt to tell you about this – you have to go and listen to it! It’s a concept album, its very funny, full of social commentary. There’s rap, to country music – imagine! There’s much talking – its got ATMOSPHERE fizzing to the tip of the champagne glass he offers you at the start. It was removed shortly after its initial release, for offending loads of people with the song ‘Rape’. Listening to it as the feminist I am, I think its not meant to be taken literally at all, and there was a lot going on in there about attitudes of the times, being mocked, quite harshly.

But the true gem, of any length or consistency, that I have – that, as a nation, WE have – is his excellence in the ITC shows Department S, and then the spin-off Jason King, where Wyngarde is a novelist, international travelling playboy and sleuth, as only the early seventies could dress and cast a man. I mean, look…

People make much of how kitsch these series are today; how camp, how unreal, how …silly. Now. You’re talking here, with someone who violently adores Flash Gordon, so are these things going to bother me in the slightest? I really think not. It is all silly, and light; and yet so disarming. Fun. Escapist. Occasionally very clever in terms of story telling, and even thought provoking. The ensemble of the team of the Department S series was great, and it’s quite shameful that it was only the one series. But then there was Jason King, so at least my favourite character is still about.

He would say things like ‘I abhor violence’, before gracefully launching himself across a room to box someone’s ears in that very theatrical and obviously unreal way they did in those TV days. And his hair would not ruffle; his handkerchief would remain dandily in the pocket. And you can’t see it, but his sleeve turnbacks would also remain blissful and unpeturbed. I have no idea why this is so important to me; I think it ties in to my sense of screaming for order in a life of chaos. Wyngarde’s portrayal of Jason King managed to make me actually want to BE him as this character. He managed to be astonishingly arrogant, yet also vulnerable and emotional. Intelligent, and strangely clueless at times. And so stylish in terms of fabric and colour that I think it really did get burned into my brain forever and affect the way I see clothes even now.

I think what I saw there, in his portrayal of that character was an amazing ability to disregard the categorisations of other people, and sail through life as HIMSELF. To not be afraid, to not be cowed, to speak out and say your piece and hold your head up while doing so. And not be afraid to be clever.

And then you see Peter Wyngarde’s actual life, and see that for the time he was in, he was too big to handle, too large for the life around him, for the narrow minded among us. He did get cowed, in the sense that his career got stalled so badly he had to go and do theatre work abroad and it never really recovered here when he got back.

Long Live the Peter Wyngarde of the past, the present, and the imagination… King of Cool, and Much Underrated Brilliant Actor. May I take on those traits I see in him, and glide through life with the same casual insouciance and verve. I wish I may.