A rare photograph of plucky fascist tot Tiny Enid.

Monthly Archives: April 2012

On Cocking A Snook

Q – What is your claim to fame?

A – My claim to fame, though modest, is one of which I am tremendously proud, and which I never tire of shouting from the rooftops, with the aid of a Tannoy. I cocked a snook at Pook Tuncks.

Q – That is flabbergasting. Tell us more.

A – Gladly. One springtime day I was bustling along the boulevard, bustle bustle, when across the way I spotted Pook Tuncks. He was standing, stock still, in the lee of a linden tree, lost, I thought, in thought. I hailed him. “Ahoy there! Pook Tuncks!” I boomed, “Thou Jesuitical duck-mesmerising versifier!” And I cocked a snook at him, and bustled on along the boulevard without waiting for a reply. When cocking a snook, one does not entertain a response, or the point is lost.

Q – What happened next?

A – My bustling continued until I arrived at a snackbar. It was called Big Pingu Snackbar and was situated at the intersection of the boulevard and Erebus And Terror Street. It is no longer there. The property is now I think a palazzo di tat. This then extant snackbar I entered, and strutted to the counter, where I ordered a snack before sitting down at a table by the window where I had a good view of the boulevard. I had bustled too far along from Pook Tuncks and the linden tree for either to be visible, though other linden trees I could see.

Q – What form of snack did you order?

A – A pickle-packed sandwich and a beaker of milk. Service at the snackbar was woeful, which is perhaps one reason why it closed down. I had to wait a long time, sitting looking out of the window, before a grim-faced bepimpled sallow stooped skivvy brought my snack to the table. No napkin was provided, so there was an altercation. I insist on several napkins in snackbars, one for my lap, one on which to wipe my hands, one with which to dab my lips, one to mop up any spillages I might cause during my snacking, and one for later use, which I pop into my pocket. But I was given no napkin at all, until I made loud complaint. The loudness was unassisted, in that I did not have recourse to the Tannoy I use nowadays to bruit my claim to fame abroad. My voice can be loud enough in the confined space of a snackbar, and the Big Pingu Snackbar, despite its name, was not a big snackbar. The skivvy was at first unwilling to bring me a napkin, which I thought odd. Surely, I thundered, the napkin is an essential component of any snackbar’s toolkit? My use of the word “toolkit” as it is deployed by management consultants and pointyheads bewildered the skivvy, or at least she pretended bewilderment. It was hard to tell. In my experience snackbar skivvies can be past masters at dissembling. My insistence and loudness and eye-popping frenzy did persuade this one to fetch my napkin, but she brought just one. I lowered my voice, just a tad, and explained that I required several napkins, though I did not itemise the uses to which I would put them, as I have done for you. It was not, in my view, any business of the skivvy’s. I was patronising the snackbar and I wanted my napkins, it was really as simple as that.

Q – This is all very interesting, but what of Pook Tuncks? Did he detach himself from the lee of the linden tree and pursue you into the snackbar?

A – I have yet to conclude the anecdote of the napkins.

Q – Well, let us pass on that. I think the listeners are agog re Pook Tuncks.

A – It is, I promise you, an anecdote both instructive and amusing and well worth the hearing.

Q – Be that as it may, this programme is called “My Claim To Fame”, not “Napkin World” or “Annals Of The Snackbars”, and your claim to fame is that you cocked a snook at Pook Tuncks, so perhaps we could concentrate on that.

A – I would not want it to be thought I am some kind of napkin monomaniac, so, reluctantly, I will desist. But I must ask, do those napkin and snackbar shows exist, or did you just make them up for the purposes of your argument?

Q – I am merely the host and presenter and, if you like, anchor of “My Claim To Fame”, so I am not familiar with the full schedule of programmes. I cannot say for certain whether those I adverted to exist or not.

A – Could you find out, while I sit here twiddling my thumbs?

Q – Now is not the best time. Perhaps at the end of the show you and I could go together to see the programme director, within whose head is gathered such a body of knowledge of the schedules that it would dazzle you.

A – That sounds like a capital idea.

Q – So, Pook Tuncks…

A – And if there is not currently a snackbar and napkin strand, then I would be happy to present such a programme, daily, at breakfast time, or even before breakfast, at dawn, or before dawn, in the middle of the night.

Q – I am sure the programme director would be only too willing to discuss that with you.

A – Good, that is settled then.

Q – Then let us proceed. Did Pook Tuncks come crashing into the snackbar, hot on your heels, to berate you for cocking a snook at him?

A – No, he did not. I never saw hide nor hair of him again, ever after. I like to think my cocking a snook at him must have given him pause, and caused him to retreat, away from the boulevard and the lee of the linden tree, into reclusion and solitude and the bleak existence of a hermit, shuttered in a hut on a remote promontory far from humankind. Such is the power of my snook, when cocked.

Q – Gosh.

[Tinkly, hesitant, music, followed by the weather forecast.]

On Flocks Of Birds

Often, if you are out of doors and crane your neck at such an angle that you are looking up at the sky, you will see a flock of birds. Not always, but often, often enough in any case to make my opening sentence credible. I strive, as a writer, to be credible. I think all writers do. We want readers to believe what we are telling them, if only temporarily, during the act of reading. This is the case even with persons who write of outlandish and preposterous things, for example those kinds of science fiction stories set in the distant future on far-flung planets, where characters with names like Zybog and Kagvond try to prevent an explosion at the weapons facility on Planet X-47215, while menaced by intergalactic beings with tentacles and metallic parts. This is obviously tosh, but the writer will try to make it credible. As soon as you put the potboiler or pulp magazine aside, you can dismiss what you have just read as piffle. The important thing is that you believe it while you are reading it.

So I do not think it is outwith the bounds of reason to claim that, in peering up at the sky, you will often see a flock of birds. It depends where you are, of course. Some areas are more bird-haunted than others. If you are in a desert, you might see a flock of vultures, circling over potential carrion, but probably not as often as, at the seaside, you might spot a flock of seagulls. In fact at some seaside resorts, particularly those with gigantic rubbish tips in the vicinity, it is hard to look up at the sky without seeing teeming seagulls. The desert and the seaside are extreme cases, geographically, but the fact that in both, or rather above both, one might glimpse flocks of birds is telling, I think, in terms of my argument.

Not all birds fly about in flocks. Come to think of it, not all birds fly. The ostrich, for example, is a flightless bird, and a remarkably stupid one. That being so, you are unlikely to read a sentence such as

Above, a huge flock of ostriches swooped in the blue sky, silhouetted against the blazing sun at noon on Thursday.

which would probably cause you to fling the book across the room in exasperation. On the other hand, you might find it credible if the sentence was

Above, a huge flock of ostriches swooped in the beige sky, silhouetted against the blazing suns at noon on Thursday at the weapons facility on Planet X-47215, where Zybog and Kagvond were doing battle with intergalactic beings with tentacles and metallic parts while trying to prevent an explosion which would have unforeseeable effects on the space-time continuum.

In this context, flying ostriches might be credible. Much depends on your tolerance for science fiction. If it is low, you might still fling the book across the room in exasperation, and go to find something else to read.

If a writer wishes to entertain you, however fleetingly, with a scene in which a flock of birds is visible in the sky, they will need to do a spot of ornithological research to ensure that the birds they mention are indeed ones that fly about in flocks. One of the reasons for this is that no writer is omniscient, and it may well be that among their readers are persons who know more than they do about particular subjects. The ignorant but wily writer can get around this by being non-specific, as in this example:

“Gosh, Primrose, look! There is a huge flock of birds in the sky!”

The risk here is that the ornithologically-competent reader could find themselves wondering what type of birds, precisely, are being pointed out to international woman of mystery Primrose Dent in your exciting espionage thriller. In their wondering, they are likely to become distracted and disengaged from the convoluted plot you are doing your best to keep moving briskly along, and they might fling the book across the room in exasperation. It would be better, then, to write

“Gosh, Primrose, look! There is a huge flock of starlings in the sky!”

as starlings do in fact fly in flocks. Your bird-brainy reader will be entertained, and may even impute to you more ornithological knowledge than you actually possess. This is not without its own risks, but generally speaking the reader will bask in their delusion so long as you do not get too carried away. Just because you know that starlings fly in flocks does not mean that you can start blathering on about their feeding habits, nesting patterns, lore and legend, and what have you, unless of course you already know about these things. If you do not, but still feel impelled to write about starlings’ feeding habits, nesting patterns, lore and legend, etcetera, to add a piquant starlingy quality to your prose, then for God’s sake submit your manuscript to a trained ornithologist before unleashing it upon the world. This is particularly important if, in devising the character of international woman of mystery Primrose Dent, you decide it would be apt to make her a starling expert. If you cannot be bothered to do the research, or cannot afford the services of an ornithology adviser, your best bet would be to make Primrose Dent an intergalactic woman of mystery, and have her scooting about bent on espionage at the weapons facility on Planet X-47215. That way, she can be an expert on space-starlings rather than real, earthly starlings, and you can write whatever you like about their feeding habits, nesting patterns, lore and legend, etcetera, because you will be making it all up. Just don’t forget to make it credible.

It may be that you wish to peer at flocks of birds in the sky without ever writing a word about them. In that case, take a pair of binoculars and a packed lunch, and stride up into the hills, and gaze. Even in areas less bird-haunted, sooner or later a flock of birds will appear in the sky, God willing.

Simple Dabbling

Over at The Dabbler today, I examine an episode from the life of the noted simpleton, Simple Simon. His adversary, the pieman, also appears in this tale, and not, it must be said, in a good light. As in all the best fables, a moral is drawn at the end, though not a very enlightening one.

On The Vilification Of A Totnes Undertaker’s Mute

One would not think an undertaker’s mute would attract vilification. That, however, was precisely the fate of a blameless little Totnes undertaker’s mute in the early years of the last century.

The typical undertaker’s mute – and the Totnes mute was nothing if not typical – was a ragamuffin street urchin, plucked from the squalor of the stews and rookeries, dusted down and primped up, togged out in black and with a top hat usually too big for his undernourished head, and paid a penny or two to march at the head of a funeral procession, mawkish, mournful, woebegone and mute. Why on earth would anybody vilify such a mite?

It is not that the Totnesniks were a peculiarly vindictive lot. As everywhere else, they had their good and bad. Most of them, faced with a funeral procession making its way slowly through the Totnes streets, would stop, and bow their heads, and remain silent and solemn. Some would weep. Yet even the weepers, when they spotted the tiny mute, would cry out insults and imprecations, and in some cases even death threats. It was fortunate that the undertaker had his horses well-trained, or they might have taken fright and bolted, and ruined the funeral. Fortunate, too, that the enraged Totnesniks satisfied themselves with catcalls and shouting, and did not shower the undertaker’s mute with rotting fruit and pebbles. As for the little mute himself, he acquitted himself honourably, through funeral after funeral, never once breaking step, in spite of his rickets, and never once retaliating, in spite of the provocation. Did he break down, or complain, or vow revenge, when once more safe inside the undertaker’s office? Or was he simply happy with his tuppence? It was, after all, a tuppence beyond the most vivid dreams of the other Totnes urchins, and would buy him oysters or eels for his supper.

The most baffling feature of the whole business is the absence of any contemporary comment in the local press. I have trawled through the archives of the Totnes Bugle & Advertiser and of the Totnes Counter-Bugle & Advertiser, and even of the Proceedings Of The Secret Totnes Branch Of The Revolutionary Workers’ Anarchist Collective Steering Committee, to no avail. It is worth pointing out, however, that some malfeasant scamp has been through the papers with a snipping tool, and several articles are missing. Would they be revelatory, if ever discovered?

What we do have is a series of memoirs, published in the 1920s and 1930s, in which the author claims to be the now adult undertaker’s mute. I Was The Vilified Totnes Undertaker’s Mute (1922), Further Reminiscences Of The Totnes Undertaker’s Mute (1929), and Now I Can Speak : Funeral Processions In Turn Of The Century Totnes, Recollected By One Who Was There, But Mute (1933) were the only books ever issued by a mysterious publishing house based, not in Totnes, but in its anagrammatic counterpart. The author himself remained anonymous. Several critics have been persuaded into vertiginous flights of fancy by the fact, surely coincidental, that the first volume appeared on the very same day as T S Eliot’s The Waste Land. Great play is made of the fact that one of the funeral processions the author claims to have mutely marched at the head of was that of “the famous clairvoyante, Madame Sosostris”. What these fantasists never point out is that this funeral is mentioned only in the 1933 volume, which also, notoriously, contains the lines “That corpse you planted last year in your garden, has it begun to sprout?” and “Twit twit twit Jug jug jug jug jug jug So rudely forc’d. Tereu”. If compelling evidence that TS Eliot was not the author of the undertaker’s mute trilogy is still required – and I fear there are nutters abroad who persist in ever more fanciful conjectures – there remains the fact that no record exists, anywhere, of a Madame Sosostris, famous or not, clairvoyante or not, dying or being buried or cremated or in any way commemorated in Totnes in the year given in the book, or for a decade on either side. I have myself trawled the parish registers, and all sorts of other archives, as assiduously as I pored over the local Totnes newspapers and workers’ collective steering committee minutes.

We then have to ask if there is a word of truth in this trio of curious volumes. It is not enough to say, as Dizzleby does, “Well if Eliot didn’t write them, Ezra Pound probably did, but he was as mad as a hatter”. Dizzleby, let us remember, has used exactly the same words when referring to dozens of other obscure works of the interwar years, not least one written by his own grandfather, who was not, I hasten to add, Ezra Pound. At least, not according to the documentation, including birth certificates, measles inoculation records, and one width swimming achievement citations, which I have been through with a fine-toothed comb, as diligently as I beavered away at the local Totnes newspapers and workers’ collective steering committee minutes and parish registers and all sorts of other archives.

My researches have led me to the conclusion that we are unlikely ever to identify the author of the Totnes undertaker’s mute trilogy. If we cannot say who wrote it, then as sure as eggs is eggs we cannot vouch for its historical reliability. It may be the case, as Dizzleby’s own daughter argued, that the little Totnes undertaker’s mute, and the vilification to which he was so shamefully subject, never existed at all, and is a mere phantasm, a spectre, a ghost. We are then forced to ask, who would make him up?, and why?

To which the answers are, I would, and for my own amusement.

On The Inner Life

Previously on Maud : episodes one, two, three, and four.

“Dust that gewgaw, Baines. As you can see, I am slumped on the chaise-longue, listless and enervated, taking dainty sips from a china cup of what I am given to understand our Irish cousins call a ’tisane o’ the morning’. It is morning, is it not? Oftentimes my nerves are so shattered that I have not the foggiest idea what time it is. That you nod your head would suggest it is indeed morning, if that was a nod and not one of those involuntary spasms to which you are prey when the effects of the opium are wearing off. It being the morning, why in the name of heaven are you not down in the kitchen in the basement preparing breakfast?”

“I took the liberty, Ma’am, of handing breakfast preparation duties today to the devil incarnate, who you will recall is chained up downstairs and is acting as my skivvy and helpmeet.”

“Ah yes, of course. It slipped my mind for a moment that Beelzebub came here by way of Porlock and I outwitted him. My, what an exciting day that was. And he is still here? But of course he is, for the chains that bind him are stout, and iron, and used to belong to my dear departed grandpapa. I remember that goodly if somewhat rancorous patriarch dandling me on his knee when I was but a tiny tot, and telling me that not the devil himself could break free from those chains. It seems he was correct in that, even if much else he told me during those dandlings I later discovered to be the most arrant piffle. Did you know, Baines, that the Ancient Greeks were colour blind?”

“No, Ma’am.”

“Well, of course they were not. I give it to you as an example of grandpapa’s piffle. He got it, I think, from Mr Gladstone’s three-volume Studies On Homer And The Homeric Age. Have you read it, Baines?”

“No, Ma’am.”

“No, of course you have not, for you are lower class. It would surprise me if you could read at all. In any case, when would you have time to read, what with all the skivvying and gewgaw-dusting and scrubbing and polishing and cooking and cleaning and fire-lighting and boot-blacking and stitching and darning and so forth to which God has so ordered things that you and your kind must devote every waking hour? Though it occurs to me that you are in the extraordinary position of having the devil incarnate to lighten your burden. I wonder if I am failing as a mistress by neglecting to give you further duties to fill the empty hours or minutes which Beelzebub’s captive presence must have afforded you.”

“That won’t be necessary, Ma’am, for I have been taking the opportunity to give vent to my inner life.”

“What wild talk is this? Pass me those invigorating smelling salts, Baines. I fear I might quite swoon away. “

“If it please you, Ma’am, I speak the truth. Ever since you and I dragged Beelzebub down into the basement and chained him there, and I have persuaded him to be of assistance to me on pain of being poked with burning hot toasting forks, he has proved of great worth as a skivvy. Thus in moments of unaccustomed leisure, for example while holding the toasting forks over the fire until they are burning hot, the better to poke the devil with, I have given free rein to wild imaginings and other fruits of the inner life. Only the other day. Ma’am, I got it into my head that the pots were pans, that the cutlery was the crockery, that the soap was the shoe polish. I turned the world topsy turvy inside my head.”

“No good will come of this, Baines. I wonder if I ought to summon Dr Slop, the mesmerist who has recently moved into the bungalow next door. He would place your head in a vice and make strangely significant passing movements of his hands and soon enough you would be back to your normal self and no longer prey to such miseries as the company of the devil has wrought.”

“Forgive my impertinence, Ma’am, but I fear you misunderstand me. I experience nought but immeasurable joy from my flights of fancy and nourishment of my inner life.”

“That is perplexing to be sure, Baines. I still think it would be best to have Dr Slop take a look at you. It is said there is not another man in Europe who knows more about the unfathomable nooks and crannies of the feminine brain. And I am sure it would be quite a novelty for him to probe the inner workings of a feminine brain of the lower orders.”

“As you wish, Ma’am.”

“But hark! From the depths of the basement I hear a din of infernal shrieking.”

“That is Beelzebub, Ma’am, announcing that he has finished cooking breakfast.”

“I suppose I must eat, for I am at the point of physical as well as mental collapse. Would you happen to know what toothsome delights the devil has cooked up for me this morning?”

“You will be having devilled kidneys, Ma’am.”

“Then I shall stagger as best I am able towards the breakfast table and take my seat, Baines.”

“Very good, Ma’am.”

To be continued…

Depressed Horse Pod

On Mail Order In The Twentieth Century

Further to yesterday’s potted history of the Malice Aforethought Press, I rummaged in a paper-midden and found a dog-eared copy of our 1988 mail order catalogue. I thought it might be of historical interest to reproduce some of the contents, in spite of the sinking feeling I had as I read my blurbs and shuddered at the, er, gaudiness of my prose.

All of these pamphlets are of course out of print, though most of the texts were collected in the 1989 paperback Twitching And Shattered. That, too, is out of print, but copies occasionally crop up on eBay or in secondhand bookshops or for auction here at Hooting Yard.

Preface

The Malice Aforethought Press was established in 1986 for the express purpose of scraping vegetable matter, rinds, and caked grime from the interior walls of a large iron bran-tub. However, this dreadful scheme met only with ignominy and ruin. Fleeing to a sanatorium in Greenland, the Malice Aforethought Press held a number of fruitless meetings with aviators, bonnibels, conspirators, dolts, ecclesiastics, fanatics, gaberlunzies, hacks, idiots, joskins, kakas, lepers, mahouts, notaries, obfuscators, polatouches, quaestors, revengers, succubae, tziganes, uhlans, vipers, wags, xemas, yahoos, and zealots. Halfway through this series of conferences, the sanatorium was uprooted from the sod and pitchforked into the demented ocean by an inexplicable force. Things looked grim. Saved from drowning by the intervention of a crumpled urchin, the Malice Aforethought Press returned to England, determined to enwrap the bran-tub in massive, fibrous blankets. Thousands upon thousands of eager volunteers had to be turned away, ejected into hailstorms through the rotting wooden portal which fronts our monstrous office. As a sop to these thousands, the Malice Aforethought Press has arranged to publish a selection of documents which lay bare the true history of the rusted cooking-pots stacked higgledy-piggledy in the corridors of a smashed-up building painted crimson…

Hoots Of Destiny

Three graphic stories. Many pictures, a few words.

1. Fun with gravel

2. L’Histoire du paving slabs

3. Why do potatoes exist?

Why indeed? An unclassifiable work of shining lucidity and brazen incorrigibility. The leitmotifs of this ridiculous publication, the keys to its charm, are many and various. One could perhaps single out an eyebrow, a hake, an inspirational choir funnel. Each copy is produced by our Frank on an individual basis; Hoots Of Destiny is part hand-drawn, part hand-written, and hand-coloured throughout. Each copy is dated, numbered, signed, and dedicated. So there. The perfect gift for bailiffs, Jesuit fathers, or menacing figures draped in grisly shifts.

Forty Visits To The Worm Farm

A hectic tale of malfeasance and calumny, set in an exciting worm farm. Whisks, turnips, and dangerous machinery abound, and the cast of unlikely characters includes Canute Hellhound, whose tremendous, ground-breaking lecture on the pith and nubs of wormery is reprinted in part. This pure and urgent work brings together the Sacred and the Profane, the Dim and the Doomed, and the Patron Saint of Worms with his Destiny. Our classic bestseller! The text is accompanied by four illustrations in which the author depicts his characters with withering intensity. If you buy only one book this year, you would be advised to seek medical help.

Tales Of Hoon

A magnificent collection of four crumpled yarns set in the dismal, sump-strewn land of Hoon, with the odd detour to its hinterland of purple hills and bauxite mines. A cast of hundreds, most of whom are called Ned, appears in these rum and preposterous stories. As a special treat, the texts are complemented by three maps and a really exciting A3 fold-out diagram, hand-coloured and unbelievably lavish. Each copy also contains a piece of sandpaper. Truly a labour of love; either that or sheer dementia.

A Zest For Crumpled Things

Twenty-six potted biographies of characters whose behaviour would be out of place in most of what passes for “fiction” these days. The texts make use of neologism, poltroonery, and reverential plagiarism of M P Shiel (1865-1947). Among those potted by Frank’s doolally pen are Maud Abdab, Cora Dwabb, Istvan Ick, Ned Lip, and Jodhpur Valentine. With twenty-six photographs from the author’s collection, rescued from an incinerator in the cellar of a ruinous building in the north of England.

The Churn In The Muck

A couple of stories; one about ponds, hotels, and hollyhocks, the other about hotels, hollyhocks, and ponds. More alphabetical excursions by Frank, who doesn’t intend to abandon this compositional device until he has well and truly wrung its neck. Biographical notes on the main characters are bunged in at the end for no apparent reason, shedding unpitying light on old favourites like Lars Talc as well as introducing some brand new gits, including Eileen Hollyhock and the Brothers Hellbag. Fully illustrated with four black & white plates by the author. A splash of colour is added by the insertion of a sheet of wallpaper in all fifty copies of this first edition, numbered and signed and all the usual shenanigans…

House Of Turps (in preparation)

The first volume in a projected series of 26 books in which the full and uproarious history of the House of Turps is dissected with a blunt pen-knife. This initial book potters about in the pre-history of the House, examining the events leading to its foundation, in particular the role played by a large number of inanimate objects including hammers, iron pots, wrestling-rings, and bandage paste. Future volumes in the series will lay bare the complete history of this remarkable institution, the whole adding up to what can only be described as a Bath of Learning, a Broth of Truth. Deceptively simple, even rambling, the construction of this first book is awesomely complicated, its intricate machinery a triumph of meldrum and binge. Illustrated by the author, as usual. Signed & numbered, as usual. Silk-screened cover, for once.

NOTE : That last blurb was written before I actually wrote House Of Turps. It remains the only one of the planned series of twenty-six ever to see the light of day. The cover was not silk-screened.

A Date For Your Diary

Few double-acts in the history of the universe have ever been so magnificent as Simon And Garfunkel Crosse & Blackwell Mr Key and Lepke B. Those who witnessed our only ever collaboration at the (now demolished) Jellyfish Theatre in October 2010 are still too stunned to speak about it, even in hushed tones.

Now, the legendary duo is reforming for Resonance104.4FM’s tenth anniversary party on the first of May. We will be on the bill alongside luminaries including Bob Drake and Kinnie The Explorer. Full details, including ticket-ordering linkage web-wizardry, here.

I strongly recommend that you attend, and whoop your cheers, and throw your hats in the air, and other such expressions of unbridled enthusiasm, including swooning with overexcitement.

On The Malice Aforethought Press

Here is a spot of small press publishing history, which might be of vague interest to a few readers.

‘Twas long, long ago, in the autumn of 1986 that my pal Max Décharné and I conceived the idea of publishing an anthology of our various drivellings. A decade earlier, Max had been a great enthusiast of punk and the DIY approach to making records – he realised his ambition of releasing a single while still in his teens. Why not do the same with the printed word? Neither of us, I think, was particularly aware of the thriving small press scene then extant, but we were only too conscious that I had a job in an office with a big humming photocopier to which I had access at weekends. We assembled fifty pages each of material, typed it out on an electronic typewriter, worked out the pagination by making a little dummy booklet, and voila!, we had an anthology. All we needed now was a title and a name for our imprint. Max had a job at the time which he absolutely loathed, and entertained murderous fantasies about his boss. Thus Stab Your Employer popped into his head without too much struggle. In the course of a phone call during which we discussed what to call ourselves, I cast my eyes along the bookshelf and spotted Malice Aforethought by Francis Iles. Hence the name of the Press was born. In retrospect, this does not seem a fortuitous choice, too redolent of an imprint dedicated to crime fiction. But we were young and stupid and impulsive, I suppose.

One hefty bout of illegal weekend photocopying later, we had fifty fat but spineless one-hundred-page booklets for sale. Ah yes, sales. Who on earth we imagined might buy this work of matchless genius, other than our friends and acquaintances, I cannot recall. Some copies we sent out on spec to persons we admired, to be met, of course, with resounding indifference – except in one case. Max had developed a great liking for the works issued by Atlas Press, and popped a copy of Stab Your Employer in the post to them. I do not think we understood at the time that Atlas was a shoestring operation with resources only marginally better than our own. As far as I know, what happened next was that Alasdair Brotchie of Atlas passed the booklet on to his friend, the artist Jane Colling, and Jane in turn brought it to the attention of her friend Chris Cutler, the drummer, one-time member of Henry Cow, and onlie begetter of Recommended Records. Chris was then in the early years of producing the ReR Quarterly, a printed-magazine-with-LP. Something I had written must have appealed to him, for I was then asked to contribute a piece for the Quarterly. Chris did not ask me himself, but delegated the request to a young man acting as a sort of typist/factotum for Recommended, Ed Baxter – who is today the benevolent dictator at the head of Resonance104.4FM. Thus were connections made that in some cases last to this day.

Max and I rattled off a second anthology, Smooching With Istvan, early in 1987. (It is in this booklet that “Hooting Yard” made its very first appearance, as recalled here.) Inspired by the sheer ease of producing works – though we did start paying for photocopying – we bashed out lots of pamphlets over the next couple of years. (There is a complete list of my own stuff here.) At the same time, Ed Baxter was tirelessly bringing into being the Small Press Group, along with allies such as Atlas and, from an older generation, the legendary John Nicholson. Max and I became keen and, I hope, useful members of the group, which arranged book fairs and published three, or possibly four, paperback Small Press Yearbooks. These directories, which included how-to-do-it guides and much else, stand as a fascinating record of activity in the last years before Het Internet changed the landscape.

Though Max and I never actually collaborated again – and, in truth, both Stab Your Employer and Smooching With Istvan simply jammed our individual pieces between the same covers – we issued our own works and expanded the press to publish others. These included Ginseng Fuchsia Lefleur, a Small Press Group friend from Canada, whose North American Freestyle Playpen Zen is possibly the rarest of all Malice Aforethought Press pamphlets – consider yourself very fortunate if you own a copy. I also fell in with Ellis Sharp, latterly of Zoilus Press and a great favourite of the Grauniad’s Nicholas Lezard. Ellis lived near me and my ex-wife used to cut his hair. She introduced us, and I think we were both surprised that we liked each other’s work. General Jaruzelski’s Sunglasses was the first Ellis Sharp work we published – the first piece credited to “Ellis Sharp” ever – and several more followed. It is as rare, I suspect, as Ms Lefleur’s outpouring. Bear in mind that many of these pamphlets came in editions of twenty-five, or even fewer. (I think one of my own pamphlets was limited to a dozen copies.)

The final Malice Aforethought Press publications were “proper” paperbacks – my own Twitching And Shattered, Max’s Beat Your Relatives To A Bloody Pulp and The Prisoner Of Brenda, and a couple of one-offs. Probably the finest thing we ever published was a selection of work by the great John Bently of Liver And Lights, another Small Press Group hero. The last book, which Max alone brought into being, was a collection by a member of the beat combo Fortran Five. My memory of this last is hazy, because I was whirling ever more rapidly towards the Wilderness Years. By the time I emerged from them, Het Internet had taken over the world, which was now, at last, ready for the true emergence of Hooting Yard.

I sometimes wonder what might have happened – or not happened – had Max not sent a copy of Stab Your Employer to Atlas.

On The Mighty Changing Orifice

I was leafing idly through one of Pansy Cradledew’s magazines when my eye was caught by an article entitled The Mighty Changing Orifice, written by one Jacey Boggs. Though the kettle was coming to the boil and I ought to have had the making of tea on my mind, I found myself riveted by Ms Boggs’ words. What was this orifice? Why was it mighty? What changes had it undergone? All these questions and more dizzied my poor pea-sized brain, and, ignoring the steaming kettle, I read on.

I learned that a hole and tube orifice “is the most common”, and is made by Ashford, Kromski, Lendrum, Louet, Schacht, and a variety of other makers. Ms Boggs chided me “not to discount them because they are unimproved,” (her italics), adding that some of her favourite breeds of sheep are unimproved. This seemed to me a non sequitur, but I made a mental note of it. I like to gain at least a vague idea of the personality of a writer whose words hold me spellbound, and knowing that Ms Boggs was an aficionado of sheep told me something about her. Admittedly, I was not sure what, precisely, it told me, but it was an arresting confession to make, in the context of writing about the mighty changing orifice. Not all of us care enough about sheep to have favourites among them, after all. I did not, at least not yet, ponder the difference between improved and unimproved sheep, in fact it was not at all clear to me what might be the nature of either an improved or an unimproved sheep.

But I cast all thoughts of sheep from my mind when I read the next line and was startled to discover “there is nothing that this orifice can’t do as long as the size is right”. Gosh!, I thought, that would explain its mightiness, sure enough. Nothing it can’t do? This “common” orifice, then, could predict the weather?, tie my shoelaces?, make a cup of tea?

Thinking of tea prompted me to put the magazine temporarily aside. The kettle had come to the boil, so it behooved me to leap up and place a teabag in a cup and pour boiling water upon it. I gave it a manly stir and added a plop of milk and stirred it further and then I used the teaspoon to squeeze the teabag against the inner side of the teacup, and then, very deftly, for I wished if possible to avoid any spillage, I hoisted the teabag from the cup with the spoon and tossed it into the bin, and then I ran the now empty spoon under the tap to rinse it and I placed it, bowl-end up, in a cutlery container on the draining board. There it shall rest, until such time as I make another cup of tea, or until I place it in the cutlery drawer, when it is dry. Though I have described the making of tea, it is something I do so often that I need not think about the process, so all the while I was placing the teabag in a cup and pouring boiling water upon it and giving it a manly stir and added a plop of milk and stirring it further and then using the teaspoon to squeeze the teabag against the inner side of the teacup, and then, very deftly, hoisting the teabag from the cup with the spoon and tossing it into the bin and running the spoon under the tap to rinse it and placing it, bowl-end up, in a cutlery container on the draining board, my mind was still entirely concentrated on the mighty changing orifice. Had I not been carrying a teacup full of boiling hot tea I think I would have scampered back to the sofa at high speed, so keen was I to pick up the magazine and continue reading. As it was, I made my way slowly and steadily, to avoid spilling my tea, and only when the teacup was safely on the IKEA “Benko” table next to the sofa did I sit and return to reading the words of Jacey Boggs.

She had mentioned that the orifice could do anything so long as the size was right, and now she turned her attention to this size. I was not particularly surprised to be told orifices came in very small, standard, and larger sizes – I might have guessed as much – but to be then told that “Ashford offers bushings that fit in large orifices to decrease the size” set my brain whirling. Quite apart from the whole business of altering the size of the orifice with bushings, which might be something to do with the “changing” promised in the title The Mighty Changing Orifice, I was left to wonder why Ms Boggs brought up Ashford again but had not another word to say about Kromski, Lendrum, Louet, or Schacht. Did they not have their own bushings? If not, why not? It was all becoming more and more mysterious. I took a sip of tea.

If I had hopes that all would become clear, they were dashed. Ms Boggs wrote about “innies” and “outies”, that an “outie” often results in “the wrap wrapping around the extended orifice”, that some orifices require an orifice hook, that use of a Delta orifice means there is no flopping or thwapping regardless of grist, that in addition to flopping and thwapping one might, if one is not careful, encounter thumping or bouncing, and that in the 1970s Jonathan Bosworth designed an open orifice shaped like a half moon or the letter C. It interested me that Ms Boggs gave Bosworth’s Christian name, a touch not afforded to Ashford, Kromski, Lendrum, Louet, and Schacht. Was this because Jonathan Bosworth, or his orifice, was a particular favourite of hers, like those unimproved sheep?

But answer came there none. The article finished with the thoroughly confusing assertion that Bosworth had done away with a need for an orifice hook, but that a “hook orifice functions in much the same way as the half-moon”. For crying out loud!, I wanted to shout, do I need a hook or do I not?

At this point, I remembered that the magazine was not mine but Pansy Cradledew’s, and of course I did not need a hook, nor indeed one of Jacey Boggs’ confounded orifices. What I needed was my cup of tea. I threw the magazine across the room, picked up my cup, and took a hefty slurp.

The magazine, by the way, was Spin-Off, subtitled It’s About Making Yarn By Hand, an American publication from Interweave Press of Colorado. Among their other titles are Handwoven, PieceWork, and Cloth Paper Scissors.

Gladstone’s Proposal

After four nervy months, [Gladstone] came close to proposing at the Coliseum on a moonlit January evening. A few days later he did it instead by letter. It was not a proposal to sweep a young girl off her feet.

“I seek much in a wife in gifts better than those of our human pride, and am also sensible that she can find little in me,” he wrote, in a single long-winded sentence, “sensible that, were you to treat this note as the offspring of utter presumption, I must not be surprised: sensible that the life I invite you to share, even if it be not attended, as I trust it is not, with peculiar disadvantages of an outward kind, is one, I do not say unequal to your deserts, for that were saying little, but liable at best to changes and perplexities and pains which, for myself, I contemplate without apprehension, but to which it is perhaps selfishness in the main, with the sense of inward dependence counteracting an opposite sense of my too real unworthiness, which would make me contribute to expose another – and that other!”

On receiving the letter Catherine pleaded for time, no doubt hoping it would give her the opportunity to work out exactly what Gladstone meant.*

*”He really was a frightful old prig,” wrote Clement Attlee… on reading this letter in a biography of Gladstone, “Fancy writing a letter proposing marriage including a sentence of 140 words all about the Almighty. He was a dreadful person.”

from The Lion And The Unicorn : Gladstone vs Disraeli by Richard Aldous (2006)

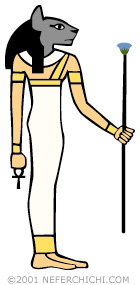

On Ancient Egypt

Two things serve to persuade me that the Ancient Egyptians were a peculiarly dim-witted rabble.

There is a tendency to regard the great civilisations of the past through rose-tinted spectacles. One thinks of Edgar Allan Poe, writing of “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome” in To Helen (revised 1836) or Neil Young babbling, of the Aztecs, that “the women all were beautiful and the men stood straight and strong… Hate was just a legend and war was never known” in Cortez The Killer (1975). I think we may safely say that these aperçus are what Ambrose Bierce, using a favourite term, would call “bosh”. What we overlook, with our romanticising blinkers, is the stark fact that much of human history was attended by filth and squalor and hunger and disease and slavery and violence and stink and flies and rats and brutality and terror and mud and ignorance. All that, of course, being your daily lot if you managed to live long enough to experience it, which untold millions, given infant mortality rates, did not.

In view of this bloody awful state of affairs, let us imagine some Ancient Egyptians, broiling one afternoon under a battering sun.

“I have an idea,” says one, “Let’s tramp into the desert and build an enormous, windowless, pointy-topped edifice of no practical use whatsoever.”

“I have a better idea,” says the other, “Let’s build two!”

Now you or I might have thought of more constructive ways to spend our time. But not the Ancient Egyptians, who went on to build over a hundred of these pointless pointy-topped buildings all over the arid hellhole where they lived. It is all very well to say that they were in thrall to a particularly vicious and mercurial pantheon of gods, but it seems to me that only supports my theory of their fundamental stupidity. Other civilisations, at other times, have also laboured under the delusion that they were ruled by deities we might sensibly consider as nutters, and dangerous nutters at that, but few have built such pointless yet enormous and pointy-topped structures. Others do exist, but not in such profusion as in Ancient Egypt.

Their enthusiasm for wasting their lives in the tremendous effort of building these idiocies is the first thing that persuaded me of their dim-wittedness. I asked myself what could have prompted such tomfoolery, and that led me to the second point. What possible hope could there be, I concluded, for a civilisation that worshipped cats?

Don’t get me wrong, I adore cats. I am definitely a cat person rather than a dog person, and have in the past had several pet cats, and never a pet dog. There are few experiences as conducive to relaxation as being slumped in an armchair with a purring cat dozing on one’s chest. But there is a deal of difference between a feeling of affection towards, say, a tabby called Tiddles for whom one is happy to provide bowls of food, and a sense of abject awe and subjection towards Bastet, or Bast, or Baast, or Ubasti, or Baset, the cat goddess of the Ancient Egyptians.

The thing we must always remember about cats is that, for all their grace and elegance and litheness and poise, they are unfathomably stupid creatures. Some will protest that an animal that has so arranged things that it can spend its life eating food from a bowl, sleeping, playing with wool or shoelaces, and chasing small mammals and birds has clearly worked something out. Perhaps so. The average domestic cat lives the life of Riley, and one I find mightily enviable. Given half the chance I would arrange my affairs likewise. But let us keep things in perspective. Far from being a divine being possessed of great power and wisdom, the cat is a halfwit. You only have to observe them, hopelessly chasing birds which – surprise, surprise! – fly away as soon as they come close, or gazing intently at nothing on the wall of a room, or toppling off a windowsill when half asleep, to recognise that, whatever is going on in the cat’s brain, it is neither complicated nor astute.

What, then, does it tell us of a civilisation that it elevates the cat to a godhead, and duly worships it? It tells us, I think, that the Ancient Egyptians must have been ineradicably thick. And the evidence is all those pointless pointy-topped buildings, constructed with unimaginable toil in the middle of nowhere, for no pressing reason.

I rest my case.

ADDENDUM : In pondering the sheer ridiculousness of the brain of the cat, I am reminded of a little geographical mystery. In the last decade of the previous century, I often had reason to visit the city of Bristol, the northern part bordering South Gloucestershire to be more precise. Looking at maps, I noticed that on many of them the area had the name “Catbrain” emblazoned across it. Yet whenever I asked a local person about this nomenclature, I was met with blank looks. Nobody I questioned had ever heard of Catbrain, and I concluded that it must have been one of those mapping mistakes which, committed once by a slapdash cartographer, was then repeated by others. I now learn, from the Wikipedia, that Catbrain – or, properly, Catbrain Hill – does actually exist, though I am rather disappointed to discover that the name has nothing to do with the brains of cats and is derived from the Middle English “cattes brazen”, which is a reference to the rough clay mixed with stones that is the characteristic soil type thereabouts. None of which explains why the locals had never heard of it. Unless, of course, it is one of those eerie English countryside locations that are kept secret from interlopers.

On The Kitchen Devil

Greetings. My name is Beelzebub, and I am the devil incarnate. You may have seen pictures of me, colour plates in books or crude engravings in religious tracts, where I am often depicted with a goaty appearance, with horns and cloven hooves and a tail. The accompanying texts attribute to me all sorts of dark powers, and give the impression that I am to be feared more than anything else in the world. All I can say is that such powers, such fear, if real, would come in extremely handy in my current predicament. For the past six months I have been held captive in the basement of a bungalow, by a neurasthenic Victorian lady named Maud and her slovenly yet devoted maidservant, Baines.

The latter is my chief tormentor, for the length of chain which restrains me keeps me confined to the kitchen and the scullery and the pantry, where Baines rules the roost. When she is in particularly vindictive mood, Baines likes to poke me with burning hot toasting forks, cackling that she is giving me a taste of my own medicine. I have no idea what she is inferring, as I have never once in my life poked anybody with a burning hot toasting fork, oh, except for the occasional sinner, who richly deserved such hot poking on account of the crimes and naughtinesses and debaucheries and malfeasance they committed before they were delivered into my care. I, on the other hand, get poked with burning hot toasting forks purely for Baines’ amusement, which seems to turn the moral order on its head. But what can I do? I am enchained, below stairs, forced to work as a skivvy.

I suspect things would not be half so awful were this not a Victorian kitchen. The sheer amount of work involved in cooking and cleaning is exhausting even to think about. I have spent entire days scrubbing the grease from pots, using hard brown soap and soda and boiling water, and as soon as I am done Baines comes a-clattering with another load of caked and filthy kitchenware. Down here in the basement, there is no window to look out upon the world, and precious little ventilation, so the air is foul with fumes and smoke. Baines taunts me and says I must feel at home, but again, I have no idea what she is talking about. The infernal realm from which I hail is like a child’s playpen in comparison.

Things started out so well. On the way to my appointment with Maud, I stopped off in the little village of Porlock on the Somerset coast, where I poisoned a couple of wells, introduced an amusing new bacillus into the cows’ milk, and blasted an orchard with firebolts. At the inn where I stayed, I joined the other guests in rustic sing-songs and games of shove-ha’penny before casting them into the pit. It has slipped my mind, but I might even have poked one or two of the more inebriated peasants with a burning hot toasting fork, as Baines suggests. When dawn broke on the fateful day, I was feeling chipper, and tucked into a breakfast of offal and hot coals.

Transporting myself from the inn in Porlock to Maud’s doorstep in a single bound, with a thousand times the leaping power of Spring-heeled Jack, I hammered my fist on her door. When she opened it, I was struck by her fragility and neurasthenia and pallor, and I intuited that she had not long awoken from an opium daze occasioned by a goodly dose of laudanum. But of course I was far too polite to mention it, merely announcing that I was a person from Porlock, come on business, which was more or less the truth. Some might cavil that it would have been more honest to say I was Beelzebub, the devil incarnate, come to strike a bargain whereby Maud would sell me her soul in exchange for… well, for whatever it was she wanted in the mortal world. By the looks of her, she would probably have been happiest with oodles more laudanum. But long experience has taught me that, honest though such a direct approach may be, it is less than helpful when deployed with neurasthenic Victorian ladies prey to hysteria and attacks of the vapours. Much better to proceed gently, to inveigle one’s way into their parlour and accept refreshments in the form of tea and cucumber sandwiches, before addressing the main business. But I made the foolish, foolish mistake of taking off my Homburg hat, thus exposing the 666 tattooed on my scalp and the hint of devil’s horns.

Chained in the cellar, in the smoke, up to my elbows in grease and boiling water, awaiting the next poke from Baines’s burning hot toasting fork, I have replayed that parlour scene over and over again in my goaty head, as if it were a clip from a horror film. I should have kept the Tarot cards in my pocket and my Homburg on my head, at least until such time as the slovenly yet devoted maidservant had awoken from her own laudanum daze and served the tea and cucumber sandwiches. I should have used the time to lull Maud into my confidence, to gaze at her with my hypnotic goaty eyes, to compliment her on her Pre-Raphaelite tresses and the decor of her parlour, the showy napery, gleaming silver, glittering glass! In the centre of the table, in a vase that had a mirror for its base, white flowers always in bloom. Arranged around the edge of the mirror, in a clever contrivance that held water, was a border of blue or violet flowers. Tall, graceful jugs and goblets of Bohemian and Venetian glass held iced and plain water, lemonade, soda-water &c. Some oranges were in an old blue and white Delft dish to her right; on the left a glass dish held some olives. A silver toast-rack stood well filled before her. A tiny fountain played over some carefully picked watercresses, keeping them fresh. Raw and cooked fruits were arranged with an eye to colour in various old china dishes about the table. “Madam,” I should have said, “You must surely have attended carefully to The Modern Housewife or How We Live Now by Mrs Pender Cudlip (1883). I commend you.”

But, fool!, fool!, I revealed my devilry too soon, and was outwitted and bound in chains and, when Baines awoke, dragged down into the basement and enslaved as a skivvy. My only solace is that I have devised a plan of escape. Tomorrow, Baines has decreed that I shall cook breakfast. Nobody, she asserts, could better prepare devilled kidneys than the devil himself. I agree. And if I have my way, the kidneys are not the only things that will be devilled tomorrow morning.

To be continued…

A Toc H Dabble

Over at The Dabbler this week, a brief note on a topic dear, I am sure, to all our hearts – the Toc H lamp!