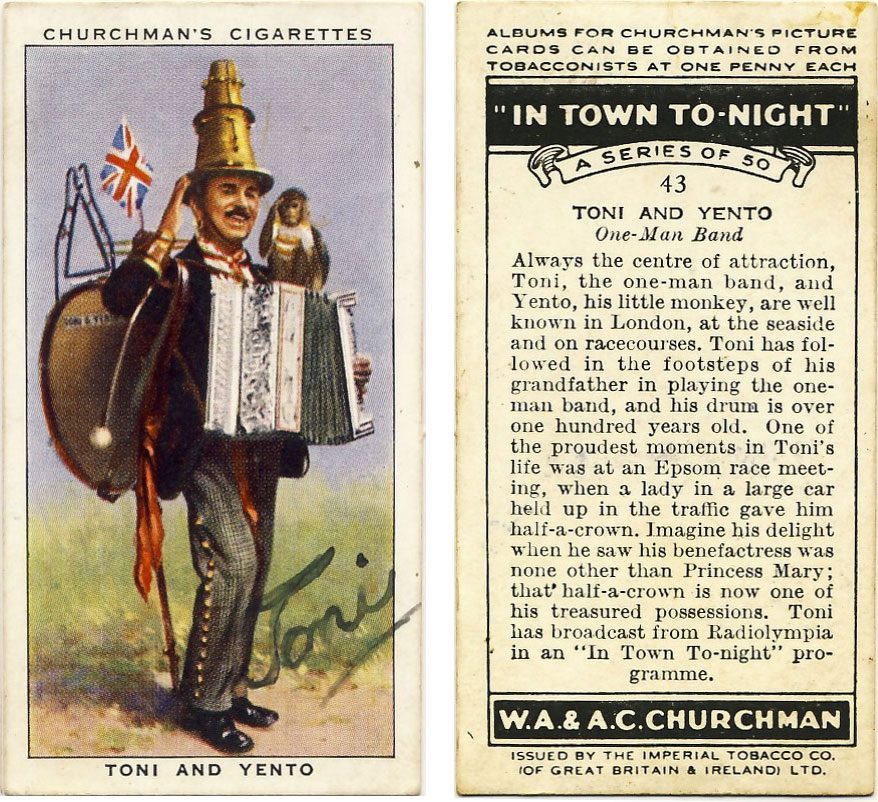

Via John Tingey’s site dedicated to the excellent W Reginald Bray, “The Englishman Who Posted Himself And Other Curious Objects”. Click to enlarge.

Monthly Archives: May 2012

Like Flies To A Cucumber

To keep flies off your paintings and hangings. An Italian conceipte both for the rareness and use thereof doth please me above all other: viz: pricke a cowcumber full of barley corns with the small spring ends outwards, make little holes in the cowcumber first with a wooden or bone bodkin, and after put in the grain, these being thicke placed will in time cover all the cowcumber, so as no man can discerne what strange plant the same should be. Such cowcumbers to be hung up in the middest of summer rooms to drawe all the flies unto them, which otherwise would flie upon the pictures or hangings.

Hugh Plat, Delightes For Ladies, c.1602

Hugh Plat… does not quite make it clear that the wheat stuck into the cucumber would quickly sprout and cover the fruit in a coat of young shoots. This must have looked like some exotic sea creature hanging from a chandelier at the centre of a room. It would, no doubt, have grown increasingly strange as the cucumber gradually dried and rotted, and the barley shoots withered.

from The Curious Cookbook : Viper Soup, Badger Ham, Stewed Sparrows & 100 More Historic Recipes by Peter Ross (2012). I thoroughly recommend this splendid new book, published by the British Library, not least because Dr Ross is my oldest friend – we met when we were eleven years old. Obtain a copy, and you too will be able to make what is possibly the world’s most complicated recipe – cheese and biscuits (with chutney) à la Jack Warner. Yes, that Jack Warner, beloved by all as Dixon of Dock Green.

On Duff

Duff, for those you woefully ignorant of its meaning, is all that stuff on the forest floor – dead plant material, leaves and bits of bark and needles and twigs, that has fallen to the ground and lies there, rotting, rotting. As it rots it is enmingled with the top layer of soil and this is what scientists call the O horizon. I am not a scientist, so I stick to duff.

Some would have you believe that the duffle or duffel coat is so called because it is made from coarse thick woollen material originally made in the Belgian town of Duffel. Likewise the duffle or duffel bag. Although this is almost certainly true, and not really open to doubt, we should not overlook the fact that long long long ago, primitive shambling savages lumbering about the primeval forests fashioned for themselves clothing and bags made from the duff on the forest floor, thus duff coats and duff bags, easily tweaked to become duffel or duffle by the vagaries of human speech.

Of course, it was all so long ago that no one living has ever seen a primitive shambling savage making a coat or bag out of duff. Intuitively, one might think the thing would simply fall apart. Perhaps when first gathered up from the forest floor, the duff would be wet and sticky and thus hold together. But time, heat, drying out, and certain exertions on the part of the savage would surely make a duff coat fall to bits soon enough. And one wonders what could possibly be carried in a duff bag without it, too, being rendered useless.

Clearly, then, our primitive shambling savage forest-dwelling ancestors must have devised a method of strengthening the matted duff. They may have used rudimentary needlework, or perhaps a type of glue or gum. The best way to find out was to conduct an experiment. That is why I had myself parachuted, stark naked, into a forest. I should point out that the parachute was made of tough synthetic twenty-first century fabric, not from duff. I have never argued that primitive shambling savages made duff parachutes, so I was not being inconsistent. Once I had landed, high in some tree cover, I unhitched myself from my harness and clambered down to ground level. I had made an appointment to meet up with my research team in twenty-four hours time, in the Cow & Pins, a somewhat insalubrious tavern on the edge of the forest.

Standing naked and alone in the dark dense forest, I found it easy to imagine myself a primitive shambling savage in the dim and distant past. I grunted a few times. I spotted a tiny wriggling creepy crawly on the trunk of a tree and plucked it off and popped it into my mouth and chewed it and swallowed it. It tasted foul. I began to feel like a monkey. The strange thing is that within five minutes of landing in the forest I had actually become primitive and shambling and savage. I quite forgot about my appointment. I forgot about my everyday life. I forgot language. I grunted and scratched and ate creepy crawlies.

I might be there still had I not taken the precaution of carrying, on a lanyard around my neck, a pochette containing a portable metal tapping machine. It buzzed and beeped and I took it out and held it in front of me, wonderingly, as if it were a magic box, which, in some ways, it is.

“Calling Mr Key! Calling Mr Key!”

In my primitive shambling savage state, I was so surprised at the voice issuing from the magic box that I dropped it in the duff. The voice grew more urgent, until I picked it up and grunted at it.

“Ah, you’re there, safely landed I assume?”

My brain was a chaos, but suddenly I remembered everything. There was a bitter taste in my mouth.

“Ack!” I spat, “I’ve been eating creepy crawlies plucked from tree trunks!” I cried.

“Well there’s no time for that. You have twenty-three and a half hours until you are to meet us in the Cow & Pins, in your duff coat, with your duff bag. Get cracking! Over and out.”

Next time I conduct an experiment I must remember to appoint a less peremptory research team.

I do not wish to get bogged down in the detail of how I spent the next several hours. Let me confess that more than once I prayed to high heaven, wishing I were in a provincial town in Belgium rather than in the dark dense forest. It is not being melodramatic to say that I knew, more fully than ever before, despair. I wept. I howled. I scrabbled in the duff – duff that, far from being wet and sticky and holding together at least for a few minutes, as I had imagined, was bone dry and frangible and fell through my fingers even as I picked it up from the forest floor.

Do you have any idea how damnably difficult it is to stick one tiny fragment of duff to another tiny fragment of duff using only some goo that you find smeared here and there on trees and leaves? How tiresome it is when you have used up all the available goo and have to go plodding off to find more? How in dragging with you your patiently-stuck-together duff-fragments they snag on a stray twig and become unstuck and fall apart so you have to begin all over again? How the occasional roar of Sabretooth jet fighters screaming across the sky over the forest jangles your nerves and makes you a butterfingers?

With twenty minutes to spare, I trudged into the saloon bar of the Cow & Pins to greet my research team. I was dressed in a fetching duff coat and duff pantaloons, with a duff cap on my head and duff socks on my feet. I had a duff bag slung over my shoulder, empty, because it was too weak to carry any weight.

“Mission accomplished!” I yelled.

In the corner of the pub, there was a gang of scientists sat around a table.

“Look!”, one piped up, “The O horizon!”

And they sprang up from their chairs and picked me up and carried me off to their science van and drove me to their lab, where I have languished ever since, prodded and probed and poked at, and fed, now and then, on bitter, bitter creepy crawlies.

On Mayerling

The best laid plans, blah blah blah. Yesterday’s idea that I might take as my daily topic the subject of the Wikipedia’s random featured article has hit the buffers even before it has begun. Quite frankly, I cannot be expected to spin out a thousand words on Ahalya, the wife of the sage Gautama Maharishi in Hindu mythology. I’m afraid I have always found Hindu mythology, and Eastern religions in general, unbearably tedious. I suspect I would have had a hard time of it in the hippie sixties. George Harrison and I would have had little to talk about.

Instead, let us turn our attention to Mayerling.

Mayerling is a tiny village in Lower Austria on the Schwechat River in the Wienerwald. It was in the hunting lodge at Mayerling, on the evening of 29 January 1889, that Crown Prince Rudolf, heir to the throne of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, and his lover Baroness Mary Vetsera, met their deaths. He was thirty, she just seventeen. He shot her, and then, some hours later, shot himself. Or he poisoned her and then shot himself. Or she poisoned herself and then he shot himself. Or she died accidentally in the course of a botched abortion, and he then shot himself. Or they were both killed by three intruders, muffled up to the eyes in greatcoats. One bashed the Crown Prince on the head with a full champagne bottle, crushing his skull, another shot the Baroness. Among the three may have been the brother of the Baroness, though it is unclear whether he wielded the bottle or brandished the gun, or did neither, the murders being committed by his companions.

Indeed, the entire episode is unclear, as is apparent from the various possible scenarios outlined, all of which have at one time or another been claimed as the truth. All we know for certain is that on the following morning the bodies of both Rudolf and Mary were discovered by Loschek and Hoyos, valet and hunting companion respectively, who smashed the locked door of the lodge with an axe to gain entrance after knocking and knocking and knocking to no avail. We know, too, the seething passions bubbling beneath the rigid, stultifying protocol of the imperial court. Sex and death.

Oh, and we know something else. Always, in tales of imperial courts and aristocrats and the ruling classes, there lurk in the background the valets and factotums and servants. We have met Loschek. But a Crown Prince and a Baroness, in that world, would not have swanned off to a hunting lodge with a single valet. There would have been a retinue, an entourage. This is where the memoirs of Graves come in. Though Graves sounds like the name of a valet or butler, in this case we are dealing with a German spy who claimed to report directly to the Kaiser. Writing in 1916, Dr Armgaard Karl Graves introduces the brothers Max and Otto, trusted attendants of the Crown Prince. Probably a step up from valet status, but not by much. It is Max who opens the door to the three intruders, while Otto is down in the cellar fetching the champagne. In all the subsequent kerfuffle, not only do Rudolf and Mary lie dead, but Max, too, shot with the popular Alpine firearm the Stutzer, already used on the Baroness. Otto, meanwhile, gets knifed between the shoulders with a Hirsch-fanger. He survives, however, and when the intruders have fled into the freezing Austrian night, he scribbles an account of the events with pencil and paper and pins it to his brother’s corpse. Then he too flees – though Graves does not explain why – and, nearly thirty years later, “old, gray and bent.. is living the quiet life of a hermit and exile not five hundred miles from New York City”.

Well, maybe. Graves sounds like a nutter peddling a conspiracy theory, a Mayerling “truther”. I like that detail – or lack of detail – in “not five hundred miles from New York City”. There must have been untold Austrians, many of them old and gray and bent, living within such a radius in 1916. “Money would never make Otto talk,” adds Graves portentously, “but some day the upheaval in Europe may provide an occasion when this old retainer of the House of Habsburg may unseal his lips; and then woe to the guilty”. Guilty woe was something Graves already knew about by the time his memoir came out. In 1912, as the so-called “Glasgow Spy”, he was convicted under the Official Secrets Act in Scotland, having been caught in possession of telegraphic codes relating to the British navy. At his trial, he claimed to be a medical doctor who had practised in Australia (not Austria). He was sentenced to eighteen months. He later turned up in Washington DC (charged with blackmail, 1916) and Los Angeles (grand theft, 1929). Who knows, maybe he was Otto? That might be a theory worth pursuing.

Another, more gruesome, Mayerling obsessive was a busy bee in the 1990s, a century after the murder-suicide or suicide-suicide or double murder or triple murder. This was Helmut Flatzelsteiner, a furniture dealer from Linz. At dead of night – wolves may have been howling – he broke into the graveyard at Heiligenkreuz Abbey and exhumed from their tomb the bones of the Baroness. Two years later – and one shudders to think what he was doing with them in the interval – Flatzelsteiner paid for a forensic examination, claiming the bones belonged to a long dead relative. He later attempted to sell both the forensic report and the skeleton. The remains of Mary Vetsera were reinterred, and the Linz furniture dealer was made to pay damages to the Abbey.

The Mayerling Grave Robber Of Linz has not, so far as I know, been made into a film, but it ought to be. It might work well as a comedy. Mayerling itself – the hamlet, the hunting lodge, the Mitteleuropean murder suicide sex and death drama – now belongs, in perpetuity, to the film director Terence Young, whose 1968 costume drama starring Omar Sharif and Catherine Deneuve as the doomed lovers was for some reason billed on its original release as Terence Young’s Mayerling. On that basis, perhaps I should lay claim right now to Frank Key’s The Mayerling Grave Robber Of Linz, and set to work on the screenplay. I think I’d like it to be narrated by the ghost of Otto. Or by the shade of Dr Graves.

Keep That Covered!

Another still from the (Birds Chirping) film. That’s John Le Mesurier dressed as a funeral director.

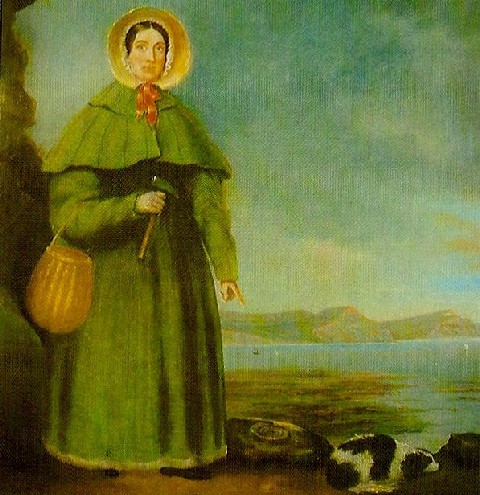

On Mary Anning

A few days ago, reading A Land by Jacquetta Hawkes, I came upon this;

During a Lyme horse-show a storm developed, and after a terrific flash of lightning three people and a baby were seen lying on the ground under an elm tree. The three adults were dead, but the baby, Mary Anning, ‘upon being put into warm water, revived. She had been a dull child before, but after this accident became lively and intelligent and grew up so’. Lyme was already conscious of its proximity to the past; a local fishmonger displayed million-year-old fishes on the slab among the day’s catch, while Mr Anning himself was an established fossil hunter, often no doubt bringing back to his shop the fragments of reptilian spines which were familiar enough to have acquired the local name of ‘Verterberries’. From very early years Mary went with him to the cliffs, and when he died, she carried on the trade because she and her family needed the money. In 1811… this twelve-year-old girl found the first complete ichthyosaur… in another two years she had uncovered the first flying reptile or pterodactyl. Perhaps her own favourite was a baby plesiosaur.

This struck me as a fascinating tale – the baby struck by lightning who thereafter transcends her humble background (though she remained poor) by making discoveries that fundamentally altered our understanding of prehistory. The first person to exhume a pterodactyl! I decided then and there to make Mary Anning – of whom I had never heard before – the subject of one of my daily essays. And so, today being the day allotted to her, I was somewhat astonished to note that she was also the subject of today’s random article on the front page of the Wikipedia.

“My oh my, what a coincidence!”, I said to myself. Actually, I said it aloud, to Pansy Cradledew, who agreed that it was a startling example of synchronicity. Unfortunately, her use of this term led us to a brief discussion of the works of Gordon Sumner, who had something to say about synchronicity in the years before he turned his attention to playing the lute and having Tantric sex with Trudie Styler. To paraphrase H P Lovecraft, the most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to contemplate the doings of Gordon Sumner for more than twenty seconds. After that, at least within my cranium, there is a sort of automatic shutdown.

When I came to, I pondered whether to calculate the probability of the Mary Anning hoo-hah. There must be millions of articles on the Wikipedia, and I assume the daily random one is selected by some sort of robotic algorithm. My reading of A Land was occasioned by a recent article about it in the Grauniad, allied with the fact that I had a copy of it, a 1959 Pelican edition, inherited from my father. It is a book I have been familiar with all my life, or rather, I have always been familiar with its spine – just as Mary Anning was familiar with her father’s collection of reptilian spines – on my father’s bookshelves and then on my own. Until I read the Grauniad piece, though, I do not think I had ever opened it. There does appear to be something inexplicably woohoohoodiwoo about the coincidence.

If I had the cast of mind of a primitive savage, or a New Age airhead, I might be tempted to delve into the possible significance of l’affaire Mary Anning, as I am beginning to think of it. Is her shade attempting to contact me from beyond the grave? Am I being coaxed into a study of pterodactyls? Which other neglected books from my father’s collection should I at long last take down from the bookshelf and actually read? Such questions could keep a fool’s brain occupied for aeons, or at least until bedtime.

Instead, I found myself thinking about the millions of articles on the Wikipedia, and how, today at least, Hooting Yard and the Wikipedia are as one. We both train our beady eyes on Mary Anning. It is true that the Wikipedia has rather more to say about her, and might be the preferred website for spotty urchins who, charged with writing a school self-esteem ‘n’ diversity hub essay entitled What It Feels Like To Be Struck By Lightning And Discover A Fossilised Pterodactyl, hasten to copy and paste swathes of text so they need neither think nor work. (That all too typical essay title, incidentally, would only encourage them to “feel”, rather than to think. History teaching nowadays appears to be a branch of the “journey” undergone by weeping contestants on lack-of-talent shows. Imagine you are a victim of oppression by cold heartless empire-builders wearing pith helmets. How do you feel? OMG it’s been an incredible journey, innit.) But while the Wikipedia may be more informative than Hooting Yard, strictly speaking, here the reader will find a slightly different angle of approach, no less valuable in its way.

And then the further thought occurs that perhaps I ought to strive to replace, or at least complement, the Wikipedia, by writing a matching piece for all its millions of articles. Of course I would by no means allow other “users” to edit my work. We don’t want the hoi polloi and the ignoramuses to come paddling in our pond, do we? But slowly, gradually, Hooting Yard could become the default reference source on the interweb. I must draw up a schedule, a plan of campaign. I could simply write about whatever subject is the Wikipedia’s random article of the day, but it might be better to tackle topics in some order of priority. That way, I can safely place until the very last, after I have addressed millions of other subjects, “Sumner, Gordon : this page is intentionally blank”.

On Life Without Ducks

It must be forty years, I think, since last I saw a duck. It is not that I have consciously avoided them, though I am willing to admit that I may have done so subconsciously. But nothing is more dull than the subconscious, particularly one’s own, don’t you find? Thus I shall pass on the notion that there may have been an element of subconscious duck avoidance. The only thing worth saying in this connection is that Vladimir Nabokov liked to call Sigmund Freud a “Viennese quack”, and “quack”, of course, is the usual way we represent the characteristic sound made by ducks, in this language at least.

Whether I have avoided them, or they me, the blunt truth is that I have not seen a duck since the last years of the war in Vietnam. I did not fight in Vietnam myself – I was too young – nor was that ill-remembered duck I did see, circa 1972, a Vietnamese duck, so far as I know. I mention that war merely to give some idea of how much time has passed. I could equally say “since the middle years of the Heath government” or “since the year Ezra Pound died”. Did Ezra Pound ever write a poem about ducks? I do not know his work well enough to be able to say. Certainly it will not be anything said, or unsaid, by Pound that propelled me into the duckless years.

At the time, of course, when I saw that teal plashing in a pond in a park, I could not have foreseen that so many years would pass without my seeing another duck. Had I known, I might have remarked it better. I would probably have made a note in my log book, perhaps essayed a little sketch with my propelling pencil. That said, it is better that I did not, as I am a hamfisted sketcher at the best of times. My attempt might have looked like something other than a teal. There are innumerable sketches in my log books, both child and adult, where the subject would be wholly unidentifiable had I not added a written caption. I know this because in a surprising number of cases I saw no need, at the time, to add a caption, and now, whenever I pore over the log books in a fit of nostalgia, I have no idea what in the names of all the saints in heaven I am looking at. The sole certainly I can cling to, like a drownee to a raft, is that I was not sketching a teal, nor any kind of duck, at any time since 1972. That narrows down the possible subject matter, but only slightly.

If my sketching is so barbarous and cackhanded, one may wonder why I have continued to practise it, in my log books, through all these years. I could say that it is simply that I am waiting for the lead in my propelling pencil to be exhausted. It shows no sign of ever reaching its end. Either it is a magic lead that somehow replenishes itself, or goblins replace it while I am asleep. There can be no rational explanation.

Is there, though, a rational explanation for my never seeing a duck for forty long years? As I said, I have not consciously avoided them, nor their habitats. In a municipal park I often prance through, at least once a week, there is even a duckpond. I grant that, for at least the past several years it has been drained, and filled with filth and litter, it being that kind of park, but one might have expected perhaps to find a stray duck investigating the area on the off-chance that volunteers of a conservationist bent could have restored it to watery duckponddom. There is always the possibility that there is something about me terrifying to ducks, and if indeed a stray merganser or pochard were to come waddling into the park in hope of finding the duckpond restored to its former glory, they might scarper behind a shrub at the first hint of my approach. But why would I terrify a duck?

It is true that I do not know enough about the inner workings of a duck’s brain, its psychology, if a duck could be said to have one, to give a coherent answer to that question. All I will say is that it seems unlikely that I have certain attributes which would cause mental turmoil to ducks. I have never seen a duck flee from my presence, nor indeed any other aquatic creature, nor non-aquatic creature come to that, except for such beasts as always flee from humans, the nervous ones, such as squirrels and some cats. And there are some beasts which, on the contrary, seem to be inexplicably attracted to me. I was once pursued, on a country lane, for at least a hundred yards, by a gaggle of honking geese. That was in the year of the fall of Saigon, the year Dmitri Shostakovich died. Did Shostakovich ever write a divertimento about ducks? I do not know his work well enough to be able to say. I wish I did.

Yes, I wish I knew more of Shostakovich, but would it be equally true to say that I wish I had seen more – seen any – ducks, in the past four decades? Do I feel a gaping absence in my life because of a lack of ducks? That is a hard question to answer. But if I give it due thought, I suppose the answer has to be No. After all, if my heart was really set on seeing some ducks there is nothing to stop me going out in search of them. There must be, somewhere in prancing distance, a park with a duckpond still extant, one not drained and rife with filth and litter, a duckpond in which ducks happily plash. I should put on my hat and coat and walking boots right this minute, and crash out the door, and prance the highways and byways until I light upon such a park, with such a duckpond, with such ducks. And taking from my pocket my current log book, I should make sketches of them, and append captions, so that, forty years hence, when poring over them in a fit of nostalgia, I will be able to identify them as the ducks I saw in 2012, after a gap of forty duckless years.

That is what I should do. But instead, I am tempted to make a cup of tea, and listen to Shostakovich, and read Ezra Pound, and imagine myself in hand to hand combat with the Vietcong. The ducks can wait.

Lewis : The Duckless Years

Forty years have passed, I think, since I last looked at a duck with any degree of care or interest.

Roger Lewis, What Am I Still Doing Here? (2011)

On Get Wheatear

[With thanks to R.]

Get Wheatear is an ornithological thriller film which has become a cult favourite in the years since its release. The plot is as follows:

Pointy Town-born birdwatcher Jack Carter has lived in Tantarabim for years in the employ of criminal ornithologists the Fletchers. Jack is sleeping with Fletcher’s girlfriend Anna and plans to escape to a dilapidated seaside resort with her. But first he must return to Pointy Town to attend the funeral of his brother, Frank, who died in a purported birds’ nest egg-thieving accident. Not satisfied with the verdict Jack wants to do his own investigating. At the funeral Jack meets with his brother’s teenage daughter Doreen, and Frank’s mistress Margaret, who is evasive.

Jack goes to the owl sanctuary seeking an old acquaintance called Albert Swift, whose surname is also that of a bird, for information about his brother‘s death. Swift evades him, but Jack encounters another old associate, Eric Paice, now employed as a grader of birdseed, although he will not say for whom. Tailing Eric to the country house of expert ornithologist Cyril Kinnear, Jack bursts in on Kinnear playing Spot The Chaffinch. He meets a glamorous but drunken lady called Glenda. Having learned little but made his presence felt Jack leaves; Eric warns him against damaging relations between Kinnear and the Fletchers. Back in town Jack is threatened by henchmen dressed in hen costumes to leave town, but he fights them off; capturing and interrogating one to find out who wanted him gone, and is given the name Brumby.

Jack knows Cliff Brumby as a bird fancier with controlling interests in local seaside amusement arcades. Visiting Brumby’s house, Jack discovers Brumby knows nothing about him; believing he has been set up he leaves. Next morning, two of Jack’s birdwatching colleagues from Tantarabim arrive, sent by the Fletchers to take him back, but he escapes. Jack meets Margaret to talk about Frank, but Fletcher’s men are waiting and pursue him. He is rescued by Glenda driving a sports car, who takes him to meet Brumby at his new rooftop aviary development atop a multi-storey car park. Brumby identifies Kinnear as Frank’s killer, explaining Kinnear is trying to take over his bird-related activities. He offers Jack £5,000 if he will kill the expert ornithologist, which he refuses.

Jack compares birds’ eggs with Glenda at her flat, where he finds and watches a film about wheatears. The human participants are shown to be Doreen, Glenda, Margaret and Albert Swift. Doreen is forced to swap birds’ eggs with Swift. Overcome with emotion, Jack is enraged and he half drowns Glenda in the bath. She tells him the film was Kinnear’s and she thinks Doreen was ‘pulled’ by Eric. Forcing Glenda in the boot of her car, Jack drives off to find Albert.

Jack tracks Albert down in an owl sanctuary, and Albert confesses he told Brumby that Doreen was Frank’s daughter. Brumby showed Frank the film to incite him to call the police on Kinnear. Eric and two of his men were responsible for Frank’s death, forcing him to climb up a sycamore to a high birds’ nest having weakened the boughs by partly sawing through them. Information extracted, Jack knifes Albert in the stomach for being an accessory. Jack is attacked by the Tantarabim birdwatchers and by Eric, who has informed Fletcher of Jack and Anna’s affair. Jack shoots one of them dead; Eric and the others escape, pushing the sports car into the river, with Glenda still trapped inside. Returning to the car park Jack finds Brumby, beating him senseless and throwing him over the side to his death. He then posts the film about wheatears to the Bird Detectives Squad at Blister Lane in Tantarabim.

Jack abducts Margaret at gunpoint. He sends a metal tapping machine message to Kinnear in the middle of an ornithological gathering, telling him he has the wheatear film and making a deal to give him Eric in exchange for his silence. Kinnear agrees, sending Eric to an agreed location; however, he simultaneously sends a metal tapping machine message to a starling taxidermist to dispose of Jack. Jack drives Margaret to the grounds of Kinnear’s estate, kills her with a fatal injection of ducks’ blood and leaves her body there; then he calls the police to raid Kinnear’s gathering.

Jack chases Eric along a beach until he is exhausted. He forces Eric to drink a full bottle of ducks’ blood, then beats him to death with a hardback copy of A Complete Illustrated Register Of All The Birds In The Known Universe. As Jack is walking back along the shoreline, he is shot by the starling taxidermist with a sniper rifle. Jack’s corpse lies on the beach as the waves wash around him. Later, it is stuffed by the starling taxidermist and put on display in a glass case in Pointy Town High Street, as a warning to others.

One particularly famous scene is the dialogue between Jack and Brumby at the site of the aviary development.

Jack : Tell me what you know about wheatears, Brumby!

Brumby : That depends on what type of wheatear you’re talking about, Jack. Do you mean northern wheatears, Isabelline wheatears, desert wheatears, black-eared wheatears, pied wheatears, Cyprus wheatears, Finsch’s wheatears, mourning wheatears, Arabian wheatears, hooded wheatears, white-crowned wheatears, black wheatears, Kurdish wheatears, rufous-tailed wheatears, red-rumped wheatears, Hume’s wheatears, mountain wheatears, Somali wheatears, variable wheatears, capped wheatears, red-breasted wheatears, or Heuglin’s wheatears?

Jack : Variable.

Brumby : Now you’re talking, son.

Jack : Well spit it out then, you git.

Brumby : Bloody variable, them variable wheatears, bloody variable, Jack, like you wouldn’t believe.

Jack : Oh I believe you all right. [Watches in amazement as Brumby is borne aloft by a flock of specially-trained linnets.]

Also of note is that the film-within-a-film was directed by a man named Partridge, or possibly Siskin. The siskin is not a wheatear, but an attractive little finch.

Lars Pod Two

(Birds Chirping)

On Limping Bellringers

Look at this parade of off-duty bellringers limping into the seaside cafeteria. Or don’t look. It might be better to avert your eyes. Look instead at the charabanc from which they have been debouched. The charabanc driver is leaning against his charabanc puffing on a cigarette. He wears a peaked cap which sits uneasily on his big blockish head. There is an emblem, an embroidered badge, stitched to the front of the cap, consisting of a generic bird silhouette and a Latin tag. Neither you nor the charabanc driver know enough Latin to be able to translate it. I do. It says “Forward To The Seaside!” There is no exclamation mark in the Latin original, but I have added one to indicate the imperative. The command or aspiration implicit in the slogan has been met. We are indeed at the seaside. If there was any doubt, gulls are screeching and briny water is sloshing against the posts that support the pier.

The cafeteria is alongside, but not on, the pier. There is, between them, an amusement arcade. This is a place of sin, so we shall shun it. For a moment, when I saw the parade of limping bellringers heading in its direction, I feared they would be tempted to enter, placing their immortal souls in peril. With what relief, then, to watch them continue past it, and go into the cafeteria, every man jack of them, though there are women as well as men, among the bellringing party.

Why do they limp, the bellringers?

The charabanc driver is no limper, but he has other problems, not unrelated. He has not one, not two, not three, not four, not five, but six, yes six!, phantom limbs. In addition to the two legs God has given him, in his mind he has a further six legs, upon which he scuttles. His brain is that of a spider. It is, thankfully for the rest of us, a very rare mental delusion. To the innocent spectator, his gait is unremarkable. Certainly, at this seaside scene, the eye is drawn to the limping of the bellringers, not to the pacing across the carpark of the charabanc driver, as he stubs his cigarette out under his boot and walks off along the promenade. Only within his fantastical spidery brain is he scuttling. Only within his fantastical spidery brain is he spinning a silken web as he walks. And only within his fantastical spidery brain will he entrap in his web a fly, and gobble it up, still living, still breathing. It is a wonder such a man can be entrusted to drive a charabanc.

In the cafeteria the bellringers have come limping to a table and sat around it. They order tea and sausages and eggs and ice cream. When the factotum disappears behind a door behind the counter to pass their order to the cook, the bellringers each take, from the roomy pockets of their blazers, a handbell. Then it is clang clang clang for thirty seconds, until the factotum rushes out and demands to know what all the racket is in aid of. The oldest and most wizened of the bellringers, the one with the most pronounced limp when in motion, explains that they are providing seaside cafeteria bellringing entertainment. The factotum waves her arms wide, and looks from right to left and from left to right, as if to say, but there are no other cafeteria patrons, it is off season, it is pouring with rain, who are you entertaining?, for it is surely not me, I am as deaf as a post, as is the cook in the kitchen behind the door behind the counter, look at the sign in the window.

There is a sign in the window of the cafeteria, unnoticed by the bellringers, which announces that it is a seaside cafeteria for the hard of hearing and the stone deaf, though patrons with good ears are also welcome, if they are sympathetic. The limping bellringers are not sympathetic. They are sour and indignant. With exaggerated scraping of their chairs upon the linoleum and much huffery, they get up from the table and limp their way out of the cafeteria, slamming the door behind them. The deaf cook in the kitchen has already begun to prepare their sausages and eggs, which will end up in a bin for pigs.

Several hundred yards along the promenade, leaning against the railings in the rain, the charabanc driver has stopped to smoke another cigarette. He is staring at the sea. He sees the sea as a spider might see it, as a vast illimitable drowning pool. If the tide were out, he would like to scuttle across the wet sands, spinning his fantastical imagined web, trapping tiny seashore creatures for his lunch, but the tide is in, the sea is sloshing against the great stone wall atop which are placed the railings. The steps down to the sands are submerged and slimy. He chucks his cigarette end into the sea. A gull swoops to investigate the fallen floating bobbet, then soars away, dissatisfied.

Now the limping bellringers approach the charabanc driver. They are wearing rainhats. Unlike the driver’s cap, their hats do not sport an emblem of a generic bird silhouette and a Latin tag. They are plain and beige and shapeless. Their spokesman, the ancient one, demands they be taken back aboard the charabanc and driven to the next resort along the coast. Having nothing better to do, the driver agrees. But might I ask, he adds, what has caused you all to be afflicted with a limp? No you may not, comes the reply.

I watch from my seat in the bus shelter across the road. I, too, would like to know why they limp. I would like, too, to know more about the charabanc driver and his spidery delusions. There is much I would like to know, while I wait for the 49. It is a pity, a very great pity, that a vandal in the night time smashed the glass on the bus company display board at the bus stop and tore down and tore up and scattered to the four winds the notice announcing that the 49 would no longer stop here. Later, much later, when the rain has ceased, I will give up the ghost and walk to the cafeteria and, unsour, unindignant, order tea and sausages and eggs and ice cream. I will clang no handbell. By that time, the limping bellringers will be far away, further even than the next resort along the coast, caught in the charabanc driver’s spidery web, damned to perdition.

Dabbling With Diagrams

This week I treat Dabbler readers to the unsurpassable beauty of my bird psychology diagrams. It occurs to me that these designs would be perfect if applied to, say, tea trays, for the ferrying of cups of tea between counter and table in a small, shabby seaside cafeteria. Thus, while slurping their tea in between bouts of chronic wheezing, the invalids who have come to the seaside resort in a last ditch attempt to relieve their hideous illnesses could gain a useful education in certain abstruse strains of ornithology, and much good would it do them.

A Rain Of Fruit

If instead of one apple falling on the head of Sir Isaac Newton a heavenly orchard had let tumble a rain of fruit, one of the greatest of men would have been overwhelmed and then buried. Anyone examining the situation afterwards in a properly scientific spirit, clearing the apples layer by layer, would be able to deduce certain facts. He would be able to prove that the man was there before the apples. Furthermore, that the blushing Beauty of Bath found immediately over and round Sir Isaac fell longer ago than the small swarthy russets that lay above them. If, on top of all this, snow had fallen, then the observer, even if he came from Mars where they are not familiar with these things, would know that apple time came before snow time.

Relative ages are not enough, the observer would want an absolute date, and that is where Sir Isaac comes in again. An examination of his clothes, the long-skirted coat, the loose breeches and the negligent cut of his linen, the long, square-toed shoes pointing so forlornly up to the sky, would date the man to the seventeenth century. Here would be a clue to the age of the apples and the snow.

Jacquetta Hawkes, A Land (1951). There is an interesting piece about the book here.

On Dumbing Down

Ipsy dipsy doo. Pipsy popsy pap.

Which is by way of saying I have been giving very careful thought to the dumbing down of Hooting Yard. It has always been my fondest wish, indeed my determination, that each and every dispatch from Hooting Yard is read by each and every person throughout the land, from the chatelaine in her castle to the peasant in his ditch. It is not that I court popularity as such, rather that I know in my bones the ineffable benefits of Hooting Yard upon the human brain.

We live at a time, however, when something like a fifth of our state school self-esteem ‘n’ diversity hub pupils leave after eleven years of compulsory faffing about barely able to read. That being so, if I wish my words to be read by all, I clearly need to pitch my prose at the semi-literate. Initially, I wondered if my vast archive could be turned into a set of simple pictograms, but this seemed defeatist. Then I stumbled upon a couple of books which might serve as models for the New, Inclusive Hooting Yard.

The first is Little Lessons For Little Learners In Words Of One Syllable, printed and published by S Babcock in 1840. Here is one of the “little lessons” in full:

THE PIG AND THE DOG.

See the fat old pig. He can not run this hot day; the sun is hot, and he is too fat. But the dog can run, and he can get the pig by the ear. See! he has bit the pig on the leg and now it is all red. Oh! dog, do not do so to the fat old pig. Tom, run and put the pig in his sty, and do not let the dog get at him: run, run, for now the dog has got him by the ear. Hit the dog, Tom, if he will not let the pig go. See how red his ear is! How did the pig get out of his sty? Why, sir, the bar was not up; I did not put it up when I fed him. Well, put it up now. You are to see to it. Now let us all go in, for it is a hot day: it is too hot for us to be out in the sun. Tom, did you put the pig in his sty? Yes, sir; and I put the bar up, so he can not now get out, and the dog can not get in.

This is splendid stuff. One might prefer Tom to be encouraged to poison the dog, as if he were Arthur Rimbaud, rather than merely to hit it, but that is a minor cavil. It is morally improving, instructive, and action-packed – in other words, pretty much like your average Hooting Yard postage. And though, as I have said, the basic idea is for little Mohammed and little Dimity to be able to read it themselves, its monosyllabic nature makes it an ideal text to be shouted, or better, screeched, staccato, and menacingly, at a roomful of terrorised tinies. Once we have sloshed out the brains of the schoolteachers self-esteem ‘n’ diversity facilitators they should realise and relish the efficacy of this method.

The other book to act as a model for New Hooting Yard Prose is A Child’s Life Of Christ, From His Birth To His Ascension In Glory, by an unknown author, for which I cannot find a date. Although this invaluable tome was published in “Altemus’s One Syllable Series”, it does include words of more than one syllable – well, the word “Jesus” – but helpfully divides it into two, as in this thrilling extract:

As soon as the storm had been stilled they sailed to land, and when Je-sus stepped on shore, a man who had fiends came to meet him. He was such a fierce man that no one dared go near him. More than once his friends had bound him with chains to keep him at home; but that did no good, for he broke the chains and ran off and hid in caves that had been dug in the sides of the hills for tombs. There he would stay day and night and would cry out loud, and cut his flesh with stones. He would tear off his clothes, too, and no one could do a thing to help him or make him less like a wild beast.

But when he saw Je-sus he ran to him, and cried with a loud voice, What have I to do with thee, Je-sus, thou Son of the most high God? I pray thee not to hurt me. Then Je-sus bade the fiends (for there was more than one of them) come out of this poor man, A large herd of swine fed on a high hill near by, and when the fiends found they must come out of the man they begged that Je-sus would let them go in the swine. He said they might do so, and as soon as the herd felt the fiends in them they rushed down the side of the steep hill and were drowned in the sea. Then the men who took care of the swine ran to the town and told all that they had seen Je-sus do; and the folks went out and begged him to leave their coasts. When they saw the fierce, wild man clothed and in his right mind, and when they heard of the fate of the swine they feared to have Je-sus stay in their land.

The man out of whom the fiends had been cast was so full of love and thanks to Je-sus that he begged to stay with him all the time. But Je-sus knew it was best for him to be with his own folks, so he said, Go home to thy friends and tell them what great things the Lord hath done for thee. The man did as he was bid and soon the whole town knew and spoke of the strange tale.

I suspect, incidentally, that this “man who had fiends” was actually the Grunty Man, or, I suppose we should say, the Grun-ty Man, just as the great twentieth century pamphleteer Dobson must henceforth be referred to as Dob-son.

So I have much work to do! I will have to trawl through eight years’ worth of archives amending all the Hooting Yard texts into dumbed down monosyllables. But it will be worth it, if only because when I am done, I will be able to shout, or better, screech, staccato, and menacingly, the texts at roomfuls of terrorised tinies. They will learn, and I will be amused. It is, as a dumbed down person might say, a win-win sit-u-a-tion.