I am often accosted in the streets by wild-eyed maniacs who block my path and jab me on the shoulder with bony fingers, demanding to be told how I arrive, each day, at a topic to write about. As I am reluctant to divulge the true nature of the Hooting Yard creative process, I usually babble sufficient nonsense to satisfy my assailant, who allows me on my way. This morning, however, on my way back from a circuit of Nameless Pond, I felt curiously impelled to tell the truth. Let me reproduce the dialogue verbatim, or as verbatim as I can recall it, to give you a glimpse into the travails of your favourite penniless scribbler.

Me – (sashaying along, humming The Final Countdown (Tempest), by the European band Sweden… sorry, I mean the Swedish band Europe).

Wild-Eyed Maniac – Oi! Mr Key!

Me – Yes, my good fellow, how may I be of assistance on this rain-drenched morn?

Wild-Eyed Maniac – (blocking my path and jabbing me on the shoulder with bony fingers) What are you going to write about today and how did you decide upon the topic? Answer me that!

Me – You mean “answer me those”.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – Quit stalling, buster, and spill the beans!

Me – Have you been reading decades-old American pulp fiction, perchance?

Wild-Eyed Maniac – Of course not! Like any sensible wild-eyed maniac, I read only the dispatches from Hooting Yard, to the exclusion of all else!

Me – Very astute, if I may say so.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – You may. But now answer my question. I mean, questions.

Me – Although I am usually reluctant to divulge the true nature of the Hooting Yard creative process, for some inexplicable reason I feel impelled to tell you how I arrived at today’s topic. Be warned, however, that my reply is only applicable to this particular day in the middle of June in the year of Our Lord MMXII.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – Bob’s your uncle.

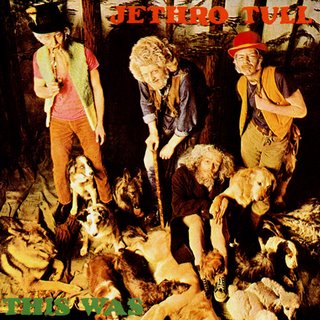

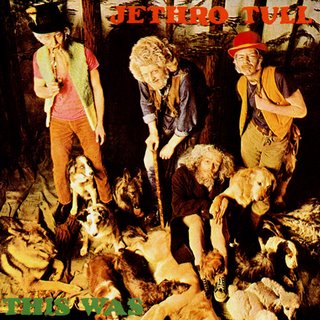

Me – In spite of the song I chose to be humming when you accosted me, I am, as you are probably well aware, curiously obsessed with Jethro Tull. God knows why. That being the case, my very first thought, on waking, before I even plunged my head into a pail of icy water, was of the early albums of Jethro Tull, and how perhaps Ian Anderson could be said to have lost his mojo circa 1974. Some would say even earlier, perhaps in 1972. Whichever date one chooses, I suspect there is general agreement that the band’s best work, and the work for which it will be remembered, yea unto every generation, appears on those first few releases. Of those, however, the debut album This Was (1968) is sometimes overlooked, possibly because of the strong blues influence and the presence of Mick Abrahams as a creative rival to Anderson – two things which are of course connected. In that sense, it is atypical of early Tull. Not having listened to it for a long long time, I tried to recall some of the songs, and the one that jumped to the surface of my brain was Beggar’s Farm. It was but a short step from there to making the decision to write about a beggar’s farm today. Not, I hasten to add, to write about the song, but instead to appropriate the title, and write some majestic sweeping paragraphs about a farm populated entirely by beggars.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – Gosh!

Me – Before I could concentrate on the ineffable glory of my prose, however, I found myself fretting away about the apostrophe in Beggar’s.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – This is absolutely fascinating, and it reminds me why you are surely the greatest living writer of English prose apart from Jeanette Winterson.

Me – You see, Anderson and Abrahams, as co-writers, seem to have had just one beggar in mind, placing the apostrophe between the R and the S. But my farm, the one gradually taking shape in my head, populated by beggars and indigents and tramps and drunks and wretches, would demand the apostrophe after the S, to reflect the plurality of beggars. Thus I was in a quandary. Should I entitle the essay On Beggar’s Farm, to reflect its fons et origo, or On Beggars’ Farm, to more accurately signal to the panting and overexcited reader what to expect?

Wild-Eyed Maniac – How on earth did you know that we Hooting Yard readers pant with overexcitement as our Windows Vista computer screens are lit up each day by your latest scribblings?

Me – I have my spies. But tell me, what would you advise regarding the placement of that pesky apostrophe?

Wild-Eyed Maniac – It’s a tricksy one, make no mistake.

Me – I think it is important that I give due credit to the monopod flautist and the founder of Blodwyn Pig. The idea of the beggar’s farm is theirs, and theirs alone, and I am merely plodding in their footsteps – or, in Anderson’s case, footstep. I have always assumed he got from place to place by hopping, at least while playing the flute.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – I have heard that is indeed the case.

Me – At the same time, I do not wish my title to be grammatically incorrect, nor to lead the panting and overexcited readers into thinking they will be reading about a farm with only a single beggar in situ. I envisage dozens, if not hundreds, of beggars, sprawled or lolloping about the farm, surrounded by rusty abandoned farm implements and machinery, growing nothing on fields reduced to scrub and gorse and bracken, rattling their tin cups at passers-by, moaning and keening and displaying a variety of unsightly sores and scars and stumps resulting from the amputation of one or more limbs. If the setting is shortly after a war, several of the beggars may have been gassed in the trenches.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – I can’t wait to read it!

Me – But wait you shall, until I am able to work out where to put the damned apostrophe.

Wild-Eyed Maniac – (his attention suddenly diverted, pointing at the sky) Oh look, a flock of swooping feathered beings with wings!

Me – They are called birds.

And so we went our separate ways, I returning to my escritoire to struggle with an apostrophe placement crisis.