Ned Mossop sat in his office nursing the last dregs of a bottle of hooch and smoking his umpteenth cigarette of the day. He stared out of the window into the gloaming, at the mean fields, like mean streets but without paving and with fewer, if any, buildings, and what buildings there were were ramshackle and dilapidated. This was a godforsaken rustic backwater, and Ned Mossop adored it.

Nothing much ever happened here, which suited Ned, but not his bank manager. He hadn’t had a case for weeks. Every day he sat in the office glugging hooch and smoking and occasionally picking a bit of straw or hay out of his hair. Sometimes, through the window, he would watch muck being spread or bonfires lit. But nobody seemed to need him. He liked it that way.

Then suddenly the buzzer on his desk buzzed. It was Velma, from the outer office.

“Ned? There’s a woman here to see you.”

“OK, pumpkin, show her in.”

Ned took his feet off his desk, knocked back the last of the hooch and shoved the empty tumbler in his drawer. And then she came in, and his eyes popped out. She was dressed in black, wearing a bippety boppety hat with a veil drawn over her face, and her figure was the kind of figure that Raymond Chandler would have enjoyed describing with a startling simile.

“Thank you for seeing me, Mr Mossop,” she breathed, in a husky voice that almost made Mossop faint with desire. He managed a peasant-like grunt.

“I had better tell you straight out why I’ve come,” she said, “It’s about my husband.”

Mossop raised an eyebrow. He had tagged her as a widow, what with the black dress and the veil.

“Or rather. . .”, she added, her voice trembling, “It’s about my husband’s cows.”

“Quit stalling, honeybunch, just lay it on the line,” snarled Mossop, curling his lip. She had not actually been stalling, but Mossop said that to all the girls.

“Please, Mr Mossop, be patient with me!” she pleaded, “You see. . . yesterday morning my husband’s herdsman discovered seventy-nine of his cows locked in a churchyard. They had somehow got in, but then the gate must have slammed shut, trapping them there. My husband thinks the cause was that gale that blew in the night. Anyway, when the herdsman released them two cows were already dead and during the day a further nine cows perished. Why? Why? Why?”

She collapsed in quivering helplessness. Mossop took a fresh bottle of hooch from his drawer, filled a pair of tumblers, and handed her one.

“Looks like you could do with a stiff drink, sister,” he growled, “And I suppose you want me to find out what happened?”

The woman drank the hooch in one gulp and said, “Well, yes, Mr Mossop. On your office door it says ‘Ned Mossop, Cow Detective’. Was it silly of me to think you could help?”

Mossop grinned a wolfish grin.

“Not at all, cherrypie. Twenty groats a day plus expenses, and I’ll see what I can do.”

She delved into her reticule and took out a handful of bent and dented and filthy coinage. Mossop took it and counted it out.

“Velma!” he called, “Get the lady a peasant with a cart to trundle her home.”

*

Later that night, Mossop walked the mean fields, all the way to the churchyard. The gate was swinging loose. He gave it a kick, and made his way among the gravestones. The grasses unloaded their griefs on his feet as if he were God, prickling his ankles and murmuring of their humility. Fumy, spiritous mists inhabited this place. The moon was no door. It was a face in its own right, white as a knuckle and terribly upset. It dragged the sea after it like a dark crime; it was quiet with the O-gape of complete despair. The yew tree pointed up, it had a Gothic shape. His eyes lifted after it and found the moon. The moon was his mother. She was not sweet like Mary. Her blue garments unloosed small bats and owls. Inside the church, the saints were all blue, floating on their delicate feet over the cold pews, their hands and faces stiff with holiness. The moon saw nothing of this. She was bald and wild. And the message of the yew tree was blackness – blackness and silence. Satisfied, Ned Mossop lit a cigarette and walked out of the churchyard, across the mean fields, as a gale began to blow. He did not shut the gate behind him.

*

“Oh, Mr Mossop! You startled me, trudging uninvited into the cowshed while I am faffing about with mops and pails!”

She was wearing the same black dress and bippety boppety hat and veil.

“Save the dramatics for your husband, sugarplum. I knew all along it was yew.”

“Me? Why, that’s ridiculous!”

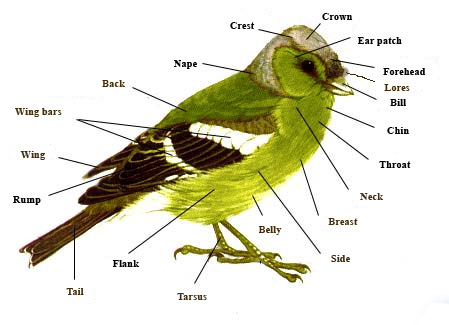

“Not you, yew. Yew trees. Your husband’s cows died from yew poisoning. The cows got into the churchyard because the gate was left open. And who left it open? Joel Cairo! But you knew that, didn’t you, pineapple chunk, because you paid him. Only not with this filthy coinage you gave me, which I am throwing into the muck at your feet in a gesture of contempt. No, you paid him in contaminated milk from your husband’s herd. You’re taking the fall.”

And as he spoke, a police car screeched to a halt outside the cowshed.

*

From The Last Englishman : The Life Of J. L. Carr by Byron Rogers (2003):

On 27 October [1967] the Archdeacon wrote again, this time enclosing a letter from Maxwell Elliott, a local farmer. “We have 80 dairy cows grazing regularly in the fields adjoining the church, and we have a continued problem of keeping the churchyard gates closed. On Monday night, Oct 16, one of the gates had been opened some time after 6 pm, and every cow except one spent the night in the graveyard. Our herdsman found them at 6 am with the gate closed on them, presumably by the gale which blew in the night. Two cows were already dead, and altogether 9 died in the course of the day, all proved to be by yew poisoning. There are 3 yew trees in the churchyard.”