Today is Eurovision Song Contest Eve, and over in The Dabbler I present some thoughts, penned earlier in the week after watching the first semi-final. Chief among those thoughts is the wisdom, for a contestant, of being accompanied by your priest. All together now . . . ♪♪♪ “My lovely horse . . .” ♪♪♪

Monthly Archives: May 2013

The Drums, The Drums

The pounding of those infernal drums began shortly before dawn. I could hear them, in the distance, from far across the wild and desolate tarputa. It was not a regular, rhythmic pounding, but a drum din more disturbing, a clattering cacophony of bangs and rattles and thumps and booms, as if a thousand Chris Cutlers were improvising simultaneously. In the folding camp-cot next to mine, Carruthers stirred.

“My God!” he said, “What is it? Your countenance is ghastly, and the blood has drained from your face, which is twitching horribly, like Herbert Lom in the Clouseau films.”

“It’s the pounding of those infernal drums, Carruthers,” I replied, “Can you not hear them?”

“Bit of a problem with the old hearing, actually,” he said, “Since that savage aimed his blowpipe directly at my eardrum the other day.”

I had forgotten the incident. I had forgotten much of what occurred on our journey to the edge of the tarputa. Sometimes it is easier to forget.

I stepped out of the tent, lit my pipe, and took a deep draw on the filthy Kirghiz scrag tobacco. The sun was rising now, over the tarputa, and the din of the drums grew louder and more ominous. Carruthers joined me, lit his own pipe, and muttered something about eggs.

After breakfast, sitting in our folding camp-chairs, smoking our pipes, we gazed dully across the wild and desolate tarputa. Every so often the bleak expanse of nothingness was broken by a swooping bird or a distant, scurrying gazelle. The drumming continued without cease, still increasing in volume, though not yet within our sight.

“Can you hear it yet, that infernal pounding?” I asked.

“Yes, faintly, in my good ear,” said Carruthers. His face too was now twitching horribly.

“Soon enough whoever is making that godawful racket will appear on the horizon,” I said, “We must devise a plan.”

Carruthers spread our map out on the folding camp-table. We pondered our position, on the edge of the tarputa, with the Big Frightening River behind us. To hide in our tent would be unmanly. But our folding camp-rocket launcher was out of commission, having been gnawed to ruin by an army of ferocious biting ants.

“What if we covered ourselves in vividly coloured dyes and posed as savage gods?” suggested Carruthers, “We might strike terror into them, and they would turn tail and scamper back to wherever they came from.”

“But who are they?” I said, “We do not yet know with whom we are dealing.”

“Fair point,” said Carruthers, relighting his pipe, which had gone out.

I set up the folding camp-sundial to ascertain the time. It was nearly midday. There was still no sign of the infernal drummers, yet the noise they were making was now deafening.

“More eggs?” said Carruthers. We wolfed down our lunch.

Suddenly, on the far horizon, we could see them. Far from being a thousand, they were just three in number. How in the name of all that is holy did they create such a tremendous and terrifying din?

Two against three. Carruthers and I looked at each other, jutted our jaws, and, in unspoken compact, agreed that our chances were better than good.

“Let us wait until we see the whites of their eyes,” I said.

And so we sat awaiting the drummers as they slowly approached across the wild and desolate tarputa. To muffle the din, I stuffed cotton wool into my ears, and Carruthers plugged his good ear with a half-sucked boiled sweet. We smoked our pipes.

At last, shortly before dusk descended upon the tarputa, we saw the whites of six eyes. I stood up, and shouted.

“Halt!” I cried, “Step no further, or you will have to answer to the might of the Empire and the fury of the Queen! Now cease your infernal drumming and tell me who you are and what is your business!”

And then I learned, and Carruthers learned, that we had found the Urbane Blodgett Electronic Percussion Trio, long thought lost, having vanished somewhere in the vast and desolate tarputa twenty years before.

Madness

I am currently reading blockbusting paperback bestseller Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. It’s a page-turning thriller which I am much enjoying, in a blockbusting paperback bestseller page-turning thriller kind of way. But I reach page 260, and lo! there is a sudden and awful clunk! Until now, all the dialogue has been believable – you can imagine the characters speaking the words Ms Flynn puts in their mouths. But would anyone, in any circumstances, ever, say:

“I think that’s it. Yes, Amy is using a Madness song to give me a clue to my own freedom, if only I can decipher their wily, ska-infused codes.”

I shall be looking for opportunities to say this as often as possible in future.

To Cut A Long Story Short

Like Tony Hadley of Spandau Ballet, I am beautiful and clean and so very very young. Well, that is not exactly the case. I am unprepossessing, faintly grubby, and middle-aged. But then, Tony Hadley is no spring chicken either, if not quite as old as me. But, all else being equal, and notwithstanding brute reality, and both having my cake and eating it, I think I can justly claim to have beauty and cleanliness and youth, in comparison with certain others. A one hundred year old toad, sitting in a bog, for example. Put me next to that toad – on a dais, so I remain unsullied by bog-filth – and I think you would have to agree that if one of us is beautiful and clean and so very very young, it is certainly not the centenarian toad. We will not invite Tony Hadley into the line-up.

Toads do not feature largely in the Spandau Ballet story. Indeed, they do not feature at all. I have read the literature, all of it, repeatedly, far beyond what is reasonable, and I can tell you there is not a toad to be found anywhere, not in The Spands : Harbingers Of Pop, nor in Ooh Ooh Ooh, This Much Is True, nor in The Spandau Ballet Pop-Up Picture Book, nor in any of the other several dozen volumes under which my bookshelf creaks. This is, I think, a great pity.

Much would be explained were we to learn that the Kemp brothers, or Tony Hadley himself, kept, as a child, a pet toad. (I know there were a couple of other Spands, but nobody remembers who they were, or cares, other than their immediate families.) Ask me to explain what, precisely, would be explained, and I will make a fastidious gesture with my hands, and snort, and arrange my features into a withering look – a look that withers.

Did Googie Withers ever listen to, say, Chant No. 1? It is one of the greatest regrets of my life that I did not grab the opportunity to ask her this question before she died, a couple of years ago, at the age of ninety-four. Not that I had the opportunity. I never met her. But I could have ferreted about for an email address or contact details, and put my query. I feel sure Googie would have replied.

Of course, I have other regrets, many, oh!, many. And in all honesty, it is probably not true to say that the Withers/Chant No. 1 regret is among the most heart-wrenching of them. Not really. When I said it was, I suppose I was just trying to lend myself airs. It’s a common failing, but I shouldn’t make excuses. I know that now. And I know it because I have spent untold hours listening, at top volume, to the point where the neighbours complained to the police, to the entire Spandau Ballet discography, including out-takes and demos, on a loop, while gazing at large high definition hyperrealist pictures of toads, with a magnifying glass. You should try it some time. If there is a better way of clearing one’s head of cobwebs and faff, I don’t know what it is.

Vain Pig

“Vain pig, vain pig

How did your ego grow so big?”

“I am the pig of whom it’s said

‘That pig has an enormous head’

I am the central being of the universe

Which is both a blessing and a curse

My vanity I need not justify

I reign supreme within my sty

I reign supreme over beasts and men

I bow to no one save that hen”

“What hen? I see no God-like hen.”

“It is invisible, beyond man’s ken”

An Evening With Jean-Luc Git

[With thanks to Banished To A Pompous Land.]

It was a stark and doomy night; the rain fell in torrents – except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in Pointy Town that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

By the light of one such scanty flame, had we a view of the scene, we might have spotted, prancing along the windswept street, muffled in a stylish Piet Van Der Groot greatcoat, that titan among cultural theorists, Jean-Luc Git. Slung around his shoulder was a satchel, and in the satchel was a copy, hot off the press, of his latest book. Did I say book? It was not a word Git used. He called it a texte or a (dis)course, of course. On this stark and doomy night he was on his way through the gusty streets of Pointy Town to read selections from his texte or (dis)course to a tavern full of intoxicated intellectuals.

They were intoxicated both by booze and by ideas, and nobody had better ideas than Jean-Luc Git. So the tavern’s hubbub was stilled, and there was an expectant hush, as the cultural theorist came crashing through the door. Without removing his stylish greatcoat, he crossed to the low stage where a lectern had been placed. Next to the lectern was a table on which stood a small glass containing a spiritous liquor of vivid hue. Git swigged it, took his texte or (dis)course out of the satchel, opened it on the lectern, and began to declaim.

For half an hour or so, everything went tickety-boo. Git recited his clogged impenetrable prose and the intellectuals furrowed their brows, nodded sagely, and tugged at their goatees. But then the cultural theorist said:

“… and so, in what we might call the helix of disengagement, we interrogate notions of structure, unstructure, dis-structure, mis-structure, and ur-structure by way of an investigation, doubly incoherent, both formal and informal, of the punctum of jouissance …”

From somewhere in the audience, there was a titter, which turned to a chortle, and very soon became a guffaw. It was followed by a heckle, couched in language so unseemly it is not fit for family reading. Git was stopped in his tracks.

“I beg your pardon?” he shouted.

“You heard what I said,” replied the heckler.

“How dare you impugn my jouissance!” cried Git.

But it was as if the occasional violent gusts of winds which swept up the streets of Pointy Town had come blowing into the tavern, as if the torrents of rain on this stark and doomy night had come flooding in. In the tumult, the cultural theorist’s jouissance proved no defence. He was undone.

Discussion points for your reading group.

What is a just course of action if as a cultural theoretician one’s jouissance is impugned?.

List the personality defects of the kind of barbarian who would impugn the jouissance of a figure as titanic as Jean-Luc Git.

Using scissors and cardboard, make a paper dolly dressed in a Piet Van Der Groot greatcoat.

Which tavern in Pointy Town do you think would be so irresponsible as to allow entry to a barbarian so culturally depraved that they would heckle Jean-Luc Git?

Do you think the “scanty flame” from the lamps that struggle against the darkness is symbolic of Jean-Luc Git’s jouissance?

Sag’ mir, wo die Blumen sind?

The Tragedie Of King Alphonso

Scene One : The King’s Chamber. The King is seated in effulgent glory on his throne. The light pours out of him. Enter Sir Cleothgard, the King’s Chamberlain.

Chamberlain : May I be ushered into your dazzling presence, O mighty King?

King : Yes, yes, come in, Sir Cleothgard. Execute the necessary fawning and scraping, prostrate yourself in the muck, then hoist yourself to your feet and come clanking for’ard, but not too close.

Sir Cleothgard does as he is commanded.

Chamberlain : I bring grave news from the frontier, Sire.

King : Really? What have you been doing, galumphing around the frontier, when your duties lie here in the chamber?

Chamberlain : I thought I would get a bit of fresh air, O lord of light.

King : Did you indeed? Are you suggesting that the chamber is a fug of stale air enmixed with noisome pongs?

Chamberlain : Not for a moment, Sire. Truly, it is bliss to breathe the merest atom of air in the vicinity of your regal presence. And rest assured that all the while I was gallivanting I was in constant contact with the underchamberlain via my cordless metal tapping machine, ready to rush! rush! rush! to your side should my services be required.

King : And now you have come rush! rush! rushing!, so what is afoot?

Chamberlain : As I said, Sire, grave news, grave news indeed. You know that those who dwell beyond the frontier are, by definition, strangers? But of course you do! You are the King, and therefore omniscient. Be that as it may, while I was out and about, mincing around the frontier lands, I had the opportunity to study the eyes of the strangers. I carried with me, as I always do, an oculoscope, crafted for me by the court wizardy man, Ulg.

King : Ulg is indeed a great servant of the crown, and the maker of many a bewildering instrument. Go on.

Chamberlain : It pains me to say it, Sire, but when I peered through Ulg’s oculoscope into the eyes of the strangers, I was begraunt a vision, reflected back at me, of your puissance.

King : Ah! My puissance! How I treasure it! You know, Sir Cleothgard, that few kings in all history have had puissance as puissant as mine?

Chamberlain : Indeed, Your Magnificence. But the puissance I saw in the eyes of those strangers was ruin’d, quite, quite ruin’d!

King : Bloody hell! Really?

Chamberlain : I am afraid so, Sire.

King : You realise what this means, Sir Cleothgard? War! It means war!

Chamberlain : I am well aware of that, Sire.

King : You must immediately prepare my army and my navy and my air force and my special forces and my black ops unit for battle.

Chamberlain : I have already taken the liberty of doing just that, Sire. They are fully provisioned and victualled and marching or sailing or ballooning off to the frontier to do battle with your foes.

King : Excellent, Sir Cleothgard. I will pin a medal on your chest in recognition of your brio. But not before you have flown to the United Nations headquarters to present our case to the Security Council. I wish to get their blessing that this is a just war, in the terms laid down by the great French writer Racine.

Chamberlain : If I might be so bold, O majestic one, why bother with those jumped-up bureaucrats and paper-pushers?

King : For the very simple reason that once I have prosecuted this war, and defeated the enemy, and my puissance is once again restored to fantasticness, I do not wish to be haunted, where’er I go, by gaggles of unruly placard-waving wankers protesting that it was an unjust or illegal war, as happened with Tony Blair.

Chamberlain : Of course, Sire, I ought to have thought of that and got Security Council clearance already.

King : Yes, Sir Cleothgard, you should. Perhaps I may not give you a medal after all, but instead have your head lopped off and stuck upon a spike.

Chamberlain : Oo-er!

King : Ho ho ho. I was only joking. Now, off you go to the United Nations.

Chamberlain : At once, Sire!

Exit Chamberlain.

Scene Two : The King’s Chamber. The King is seated in effulgent glory on his throne. The light pours out of him. Enter Sir Potipharge, the King’s Underchamberlain.

Underchamberlain : May I be ushered into your dazzling presence, O mighty King?

King : Yes, yes, come in, Sir Potipharge. Execute the necessary fawning and scraping, prostrate yourself in the muck, then hoist yourself to your feet and come clanking for’ard, but not too close.

Sir Potipharge does as he is commanded.

Underchamberlain : I bring grave news from the United Nations, Sire.

King : What now?

Underchamberlain : Your Chamberlain, Sir Cleothgard, was mistaken for the diplomat Lester Townsend and stabbed in the back by a knife hurled with expert dexterity by a dour grim agent in the pay of Phillip Vandamm, Sire.

King : Crikey! What does this mean for my puissance?

Underchamberlain : I fear it is ruin’d, Your Effulgence, quite, quite ruin’d.

They sob. Bats swoop from down from the rafters and darkness falls.

Curtain.

Musical Pig Poll

A Just War

A just war, according to Jean Racine, is occasioned when “a King’s puissance is ruin’d in the eyes of strangers”.

Gas Bill

I do not use the word “naff”, because I think the word “naff” is in itself naff. When I wish to describe something as naff, I employ a less naff euphemism, with which those who know me are familiar. By the same token, I object to the phrase “dumbing down”, which in itself seems to me an instance of dumbing down. “Infantilisation” is a possible substitute, though it does not quite capture the full meaning of “dumbing down”.

The process, whatever we choose to call it, is all around us, of course. The latest incidence occurred when I opened my gas bill. Instead of hoicking from the envelope a bald bureaucratic statement, I was horrified to find myself looking at what I mistook for a teaching aid from an infant school self esteem ‘n’ diversity awareness hub. It was all blocks of glaring primary colours and word balloons, complete with a sinister little photo-cartoon of a homunculus, the head out of proportion to the body. I begin to wonder if British Gas will accept payment in play money.

On an entirely different matter, I noted on a side panel on the front page of yesterday’s Grauniad the line: Lionel Shriver : Who cares about what I eat?, to which my immediate response, spoken aloud as I chucked the paper across the room in exasperation, was Nobody cares, Lionel Shriver, nobody cares at all!

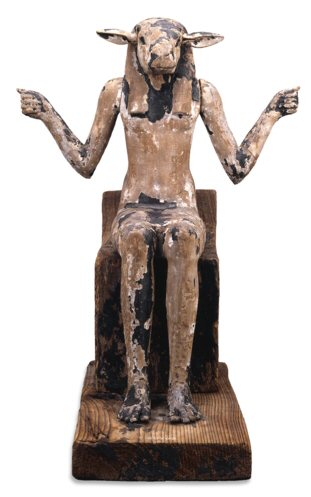

Wooden Ram God

Cheese

Cheese was rarely consumed on an allegorical level in the seventeenth century.

E. de Jongh, cited in The Embarrassment Of Riches : An Interpretation Of Dutch Culture In The Golden Age (1987) by Simon Schama. Lucky for me that I did not live in that place at that time, as my own consumption of cheese is pursued almost exclusively on an allegorical level. I shall have more to say on this matter shortly.

Mud

When I saw advertisements for the imminent cinema release of Mud, I was bitterly disappointed to learn that this is a brand new film. I had hoped it was a revival of the original Mud, that classic film dun directed by wild-eyed auteur Horst Gack.

The wrong Mud

Gack, of course, invented film dun, and was its greatest practitioner. Unlike film noir, the archetypal film dun is shot entirely in shades of dun. It was Horst Gack’s peculiar genius to recognise that there could be no better subject matter for a film in dun than mud. Thus, in Mud (1937), and its sequel, Further Mud (1957), the camera gazes unflinchingly at patches of mud, wholly dun in colour, without distracting the viewer with poltrooneries such as characters and plot and car chases and big loud fiery explosions.

“Mud is a gripping experience,” wrote the film critic Gervase Cravat in the October 1937 issue of Cravat’s Film Digest magazine, “I, for one, will never look at mud in the same way, ever again.”

He returned to the subject in the following month’s issue.

Last month I wrote that, having seen Horst Gack’s Mud, I would never look at mud in the same way, ever again. It is with a certain humility, then, if not utter self-abasement, that I must admit I have indeed been looking at mud in the same old way as I always did. The very next day after watching Mud, I was taking a stroll in a sordid rustic backwater when I came upon an extensive stretch of mud, dun in hue, and the thought popped into my head “Gosh, what a lot of mud, just like all the other mud I have ever seen in my three score years on earth”, and I pranced on, towards the viaduct and the otter sanctuary, dismissing the mud from my mind. Only when I got home several hours later, and was making a cup of tea, preparatory to putting my feet up and whistling some dance band tunes, did I realise that I had looked at the mud in the old way, as if had never seen Horst Gack’s film. This was highly disconcerting, so much so that I tightened the cravat around my neck, forgot about the cup of tea, and immediately wrote a mea culpa to Gack, confessing that his film had not, after all, had the effect on me I thought it had had, but this was almost certainly my fault rather than his. Knowing that unquestioning worship is the only proper approach to the great auteur, I added that I would atone for my philistinism by returning to the extensive stretch of mud, dun in hue, in the sordid rustic backwater, and mould from it a dun-hued mud effigy of Horst Gack himself, double life-size, before which I would prostrate myself several times a day, in between watching repeat screenings of Mud. This I have done, every day since, and boy oh boy, let me tell you, filmgoers, I am like unto a man transformed.

Clowns And Fruitcakes

This week in my cupboard at The Dabbler, you will find a letter from an inept foreign spy sent on a mission to discover what in heaven’s name is going on in the Westminster bubble. I managed to decipher the enciphered text using incredibly complicated code-breaking techniques devised by Snippage, the code-breaker extraordinaire, who cut his chops on Dobson’s mysterious pamphlet Several Observations On Kathy Kirby, Composed In A Cipher So Baffling That Centuries May Pass Before Anybody Will Be Able To Wring Any Sense From It (out of print). Of course, Snippage failed to decipher the pamphlet in toto, but without his efforts we would not even know the title, which is given on the cover as Gwzhfgsjlf seek unto them that have familiar spirits, and unto wizards that peep, and that mutter klrtfghsdjwi (uto fo pirnt).

Shoveller, Shoveller

“Shoveller, shoveller, what do you shovel?”

“I’m shovelling the muck outside your hovel.”

“Shoveller, shoveller, please desist!

I love my muck, it will be much missed!”

“Peasant, oh peasant, the muck is not yours.

I’m shovelling it off for a greater cause.

The cause of the princeling who owns your muck,

As he owns you, your hovel and your duck

And your pot and your pan and your hay and your straw.

The princeling needs your muck for the war.”

“Shoveller, shoveller, what war is that?”

“It is the war of the princeling’s hat.”

Fragment from an old folk song called “The War Of The Princeling’s Hat”.