There will be no reportage from Hooting Yard for a few days. Mr Key will be out in the field, in Cumbria to be precise, communing with sheep.

Monthly Archives: June 2013

Sitting Upon The Banister

Bartleby the Scrivener, from Herman Melville’s 1853 story of that name, is one of the most numinous characters in literature. Though fictional, he has always seemed to me to be a role model, a man to emulate if we wish to live a better life. Handily, for those of us seeking to Be Bartleby, the estimable John Ptak at Ptak Science Books has gathered into a single list all the separate utterances of our hero. Armed with the list, we can confine our own speech to the words and phrases spoken by the scrivener. Note how splendidly appropriate they are to almost every conceivable situation.

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“What is wanted?”

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“I prefer not to”

“I prefer not to”

“I would prefer not to”

“I prefer not.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“I would prefer not to.”

“At present I prefer to give no answer”

“At present I would prefer not to be a little reasonable”

“I would prefer to be left alone here”

“No more”

“Do you not see the reason for yourself?”

“I have given up copying”

“I would prefer not”

“I am very sorry, sir”

“Sitting upon the banister,”

“No, I would prefer not to make any change”

“There is too much confinement about that. No, I would not like a clerkship; but I am not particular.”

“I would prefer not to take a clerkship”

“I would not like it at all; though, as I said before, I am not particular.”

“No, I would prefer to be doing something else.”

“Not at all. It does not strike me that there is any thing definite about that. I like to be stationary. But I am not particular.”

“No: at present I would prefer not to make any change at all.”

“I know you, and I want nothing to say to you.”

“I know where I am”

“I prefer not to dine to-day,”

“It would disagree with me; I am unused to dinners.”

Me And My Eggs

I keep all my eggs in one basket. I have several baskets, obtained during what I like to think of as my “basket-acquiring years”, but there is only one in which I put my eggs. This is a small, oval, wicker basket, a bit tatty with age, which I keep on one side of the countertop in my kitchen. My other baskets I use for a number of different purposes, in different parts of the house, and outside. One purpose to which they are never, ever put is for the keeping of eggs. The eggs always go in their designated basket.

I usually buy half a dozen eggs at one time. Invariably, they come packaged in a cardboard egg-carton specifically designed for the storage of eggs. Some people are happy to leave the eggs in the carton once they get them home. That is their choice and it is not one with which I would argue, unless I was in a frantic and fractious frame of mind and, at the end of my tether, looking for a pretext to blow my top and indulge in a violent argument. Shouting my head off about the pros and cons of different egg storage possibilities can be a splendid way to let off steam. In general, though, I tolerate the practice of leaving the eggs in the carton you bought them in, so long as my own preference for putting my eggs in a basket is accepted in return. It usually is.

It would be a mistake to think that six is the maximum number of eggs in my basket. I make it my habit to buy a new carton of eggs when there is still one egg, or even two, in the basket. Thus the maximum number is seven or eight. When adding the newly-bought half dozen eggs, what I do is to remove, temporarily, the one or two eggs remaining in the basket, put the fresh eggs in, carefully, and then place the one or two older eggs, even more carefully, on top of the clutch. If I did not do this, the same one or two eggs would always remain at the bottom, and might never get used, and they would rot, from the inside, unbeknown to me until such time as I cracked the shell and released an unutterable Lovecraftian stench.

Placing the one or two older eggs atop the clutch is not without risk, of course. When removing them temporarily from the basket, I cannot simply place them on the countertop. If I were to do that, they might, being egg-shaped, roll all the way off the countertop and smash upon the floor. Mopping up egg innards and shattered shell is never a pleasant business. Thus I first lay out a tea-towel on the countertop, and put the older eggs on that, to avert any rolling. It has been suggested that I might temporarily place the older eggs in one of my other baskets. Superficially attractive as that may be, I loathe the very idea. As I insisted at the outset, I like to keep my eggs in one basket.

One great advantage of my system is that I have an empty egg carton to muck about with. Judicious use of scissors and paint and glue can transform the carton into a few hats for gnomes. There are lots of other things you can do with empty egg cartons, of course, but that is the one I always return to. My gnomes are always losing their hats in high winds.

Now. A terrible thing happened last week. I was at a swish cocktail party, leaning insouciantly against a mantelpiece, when I heard, above the hubbub, a snatch of conversation. One of the guests, in a voice as strident as a corncrake’s, said “Well, you know what they say, never keep all your eggs in one basket”. It is hard to describe the effect these words had on me. They came with the force of a thunderclap. I felt unmoored from all that was familiar, all I held dear, all I knew. “They”? Who were “they”, who said this, with such confidence, such authority? Steadying myself against the mantelpiece, I stood on tiptoe, craning my neck to peer over the heads of the partygoers, trying to see who it was who had said these awful, hideous words.

There could be only one culprit. He sounded like a corncrake, and he looked like a corncrake, and now he was saying something about not counting chickens. I clutched at the mantelpiece, fearing I would swoon. No man should be allowed to live who could utter such things. My head throbbing, I felt in my pocket for my stiletto. Damn .. . . it was not there. Panicked, I rummaged in my other pockets, in vain. Then I remembered that I had left my stiletto at home, in one of my other baskets, the big, blood-soaked one, the one in which I keep my stilettos and knives and hatchets and axes and slicers and shivs.

Source : Me And My Eggs, by the lumbering walrus-moustached psychopathic serial killer Babinsky.

Reservoir Pod

Profundity

It is high time I wrote something profound. To do so has always been within my gift, of course, it is just that I have neglected it. Oh, every single day I am beset by thoughts of great profundity, though admittedly these may oft be mistaken for platitudes, truisms, or mad ravings.

This morning, for example, as I awoke with the sunrise, at approximately half past four, the first thing that came into my head was the phrase “All roads lead to Rome”. How profound that is. We could, if we wished, worry away at it for hours and hours, like a cat with a strand of wool, and, unlike the cat, we would forever find new insights, new angles, unfathomable depths of wisdom and, yes, profundity. The cat, by contrast, being ineradicably stupid, would forget whatever it had learned about the strand of wool thirty seconds ago. I am sometimes envious of cats. Imagine how exciting life must be, to be so stupid!

Unfortunately, with my pea-sized yet pulsating brain, I am able to fret and fiddick about the five words “All roads lead to Rome” for hour after hour. I can draw from them profound insights about history and geography and the nature of what it means to be human, and much else besides. I can become lost in profundity.

By the way, I made up that word “fiddick”. Or at least, I commandeered the surname of the last editor of the much-lamented The Listener, Peter Fiddick, to serve as a verb meaning something along the lines of fretting at and worrying at something, as a cat might fret and worry at a strand of wool, as a fool might fret at an old adage. But you knew what I meant, didn’t you?

Muddy Dabbling

This week in The Dabbler I pay homage to the two heroes of my teenage years, Samuel Beckett and Robert Wyatt, and how they sort of collided, in spirit, in Wyatt’s song “Muddy Mouth”.

Do I still idolise either of them? Probably not. Beckett’s early novels remain matchless, but he wrote himself into an airless and sterile impasse. The later, shorter, fictions lack the comic energy that makes Watt a bonkers masterpiece sui generis. As for Wyatt, he still makes some fine records, but I can’t really uphold as a hero an unreconstructed communist who has that curious British middle-class leftie obsessiveness about Israel. (See also the late Iain Banks.)

N. Y. C. Lovecraft

The organic things – Italo-Semitico-Mongoloid – inhabiting that awful cesspool could not by any stretch of the imagination be call’d human. They were monstrous and nebulous adumbrations of the pithecanthropoid and amoebal; vaguely moulded from some stinking viscous slime of earth’s corruption, and slithering and oozing in and on the filthy streets or in and out of windows and doorways in a fashion suggestive of nothing but infesting worms or deep-sea unnamabilities. They – or the degenerate gelatinous fermentation of which they were composed – seem’d to ooze, seep and trickle thro’ the gaping cracks in the horrible houses . . and I thought of some avenue of Cyclopean and unwholesome vats, crammed to the vomiting-point with gangrenous vileness, and about to burst and inundate the world in one leprous cataclysm of semi-fluid rottenness.

From that nightmare of perverse infection I could not carry away the memory of any living face. The individually grotesque was lost in the collectively devastating; which left on the eye only the broad, phantasmal lineaments of the morbid mould of disintegration and decay . . a yellow and leering mask with sour, sticky, acid ichors oozing at eyes, ears, nose and mouth, and abnormally bubbling from monstrous and unbelievable sores at every point . . .

H. P. Lovecraft describes Manhattan’s Lower East Side in a letter to Frank Belknap Long, cited in H. P. Lovecraft : Against The World, Against Life by Michel Houellebecq (1991, 2005)

An Encounter With A Ragged-Trousered Philanthropist

Last time I bumped into a ragged-trousered philanthropist in the street, I berated him for his dishevelment. Would it not be meet, I suggested, were he to pay more attention to his toilet? I held before his eyes the image of Beau Brummell, as an exemplar of attention to detail in masculine dress. Do you think for one minute, I keened, that Brummell would ever have stepped out of doors wearing ragged trousers?

But Brummell was not a philanthropist, countered the ragged-trousered philanthropist, and he pressed a coin into my palm. I realised he had mistaken me for a mendicant. It is true that my own apparel was somewhat raggedy, but I can admire Beau Brummell without attempting to emulate him.

Here, have your coinage back, I said, I have no need of it.

Ungrateful swine!, shouted the philanthropist, and he slapped my face. The slap was done with his bare hand. Had it been a glove, I would have taken it as a challenge to engage in a duel. As he refused to take back his coin, I tossed it into the gutter.

Let a guttersnipe profit from your philanthropy, I said, rubbing my cheek, and away I pranced, in the bitter sunshine.

At the corner, I paused, and turned, and waited until the ragged-trousered philanthropist was out of sight. Then I hastened back to retrieve the coin from the gutter. Before I could do so, however, an eagle-eyed guttersnipe, attracted by its silvery glint, appeared from nowhere and scooped it up.

I brandished my stick and beat the urchin insensible. I prised the coin from his grasp and then rifled through his filthy pockets to find what treasures lay therein. String, elastic bands, paper clips, a boiled sweet, but no more coinage. I left the guttersnipe, battered and bloody, in the gutter, and went on my way, in the bitter sunshine.

Exercise : The narrator is clearly wallowing in a moral sewer. Describe this sewer, as vividly as you are able, and populate it with other figures, both historical and fictional, who you think are likely to be found there.

Poor Or Mad?

In an appendix to On The Writing Of The Insane, G. Mackenzie Bacon notes the similarity between the writing of the insane and the writing of the lower orders.

In the position I occupy I receive a good many letters from the poorer class, and have often had from some of my correspondents very odd specimens. The three following [which you can consult at the Public Domain Review] are from individuals belonging to what is called the sane portion of the public. In [one] the contrast between [the] style and those in the preceding pages [by certified lunatics] is perhaps not so well marked as one would like to expect.

My Fulbourn Star

“The patient was a respectable artisan of considerable intelligence, and was sent to the Cambridgeshire Asylum after being nearly three years in a melancholy mood. . . . He spent much of his time in writing – sometimes verses, at others long letters of the most rambling character, and in drawing extraordinary diagrams . . . After he left the Asylum he went to work at his trade . . . but some two or three years later he began to write very strangely again . . .

“This is one of the letters he wrote at this time, after a visit from a medical man, who tried to dissuade him from writing in this way : –

Dear Doctor,

To write or not to write, that is the question. Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to follow the visit of the great ‘Fulbourn’ with ‘chronic melancholy’ expressions of regret (withheld when he was here) that, as the Fates would have it, we were so little prepared to receive him, and to evince my humble desire to do honour to his visit. My Fulbourn star, but an instant seen, like a meteor’s flash, a blank when gone.

The dust of ages covering my little sanctum parlour room, the available drapery to greet the Doctor, stowed away through the midst of the regenerating (water and scrubbing – cleanliness next to godliness, political and spiritual) cleansing of a little world. The Great Physician walked, bedimmed by the ‘dark ages’, the long passage of Western Enterprise, leading to the curvatures of rising Eastern morn. The rounded configuration of Lunar (tics) garden’s lives an o’ershadowment on Britannia’s vortex.

“… In the course of another year he had some domestic troubles, which upset him a good deal, and he ended by drowning himself one day in a public spot. The peculiarity was, that he could work well, and not attract public attention, while he was in his leisure moments writing the most incoherent nonsense.”

from On The Writing Of The Insane by G. Mackenzie Bacon (1870). Available online at the Public Domain Review.

Rotating Withers

For me, the highlight of the recent Old Scratchy Black And White Newsreel Footage Of Tiny Fascists Film Festival was the exceedingly rare old scratchy black and white newsreel footage of Tiny Enid. The plucky fascist tot was filmed, possibly in the Old Town of Plovdiv, clomping along a street, in a polka dot dress, dragging behind her her club foot and withered leg.

This latter detail allows us to date the footage fairly precisely. In her Memoirs, written in her dotage, Tiny Enid recalled what she dubbed “the year of rotating withers”:

Then it so happened that I awoke one morning to discover that my left leg – the one which ends in a perfectly normal, as opposed to a club, foot – was withered. Being a brave and plucky tot I did not whimper, as so many girlies would have done, but dragged myself downstairs and tucked into my breakfast of milk slops, after which I got on with my day as usual.

The next day, Tuesday, my leg was still withered. But when I woke up on Wednesday, my left leg was as sound as before, but my left arm was withered. This withering lasted for three days, until the Saturday morning, when it was my right arm that was withered, while my left arm was wholly unwithered. Come Sunday, my right arm was back to normal but my right leg was withered.

And so it went on, turn and turn about, limb by limb. Only one was ever withered at a time, but invariably one of the four, either an arm or a leg, was withered, every day. Of course I coped admirably with these witherings, and never uttered a word of complaint, but I did wonder if I might ever return to being fully sound of limb, permanently, apart of course from my club foot.

It occurred to me that the unwithering of one and the withering of another must of necessity take place while I slept, for it was a discovery I made each morning when the alarm clock jangled me awake at six. I thus decided to forego sleep, and kept myself awake by singing rousing songs and smashing crockery. However, even as plucky a tot as I could only remain awake for so long before, as a poet might put it, the waters of Lethe closed over my head. When I woke up, my right leg, which had been withered, was unwithered, and my left leg was withered.

Eventually, and not before time, I decided to consult a physician. There was newly arrived in town a doctor with the splendidly appropriate name Ague-Palsy. I rapped my knuckles on his door, was ushered in, and he took one look at me and announced, in his gravelly voice, that I was suffering from rotating withers. This was not a malady I had ever heard of before, obviously, or I would have been able to diagnose it myself.

Dr Ague-Palsy proved to be an experimentalist. He was working at that time with an entirely new type of gas which he had either discovered or invented, it was never clear to me which. He prescribed a series of daily “gas baths”. The basic idea was that I filled the tub with piping hot water, pumped some of his gas into it, and then splashed about, playing with my toy ducks, for half an hour. A week of this regime, he said, and each of my four limbs would be free from withering for the foreseeable future.

I am pleased to report that this experimental treatment proved highly efficacious, and at the end of the week I was completely cured of rotating withers. He did not warn me of the side-effects of his new gas, which made me three times as plucky and reckless and fascistic as I had been before – so that was an added boon!

Children Of “Brian”

This is really important, so please read it very carefully and make every attempt to memorise it:

(COLONY)=(ANT+YES)

(FLOWERS)=(LADYBUG+GOD)

(SHIP’S OUIJA BOARD)=(AIRCRAFT CARRIERS)

(SUBMARINES)=(SOLAR WEB+GOD)

(PLANET MARS+X)=(MAGNETIC BOOTS)

(I’M A GENIUS)=(SELENIUM)

(CHILDREN OF “BRIAN”)=(666 CODE)

You will also need to familiarise yourself with what we call the “series of headings”:

COMPUTER/CYBERNETICS AND COMMUNICATIONS

INFLATION

SOCIAL SECURITY

FEAST OF TABERNACLES

EGYPTIAN ARTEFACTS

HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

DOLPHINS

CARIBOU FUR

INSECTS

MEDICINAL

INDOOR BBQ GRILL

MENTHOL PIES

WISDOM TEETH

PSYCHIC DATA BASE

MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS

SYNTHETIC OILS AND FUELS

ARTIFICIAL MUSCLES

JUMP SOLDIERS OR THE GROUND JUMPERS

ROGUE WAVES

FLYING PODS (DELPODS)

RETRACTABLE ROOF

FIRE FIGHTER

MURDER BY SLANDER

THE PAPACY

SPACE PROGRAMS

Got all that? Further details, should you require them, here.

The Dobson Archive

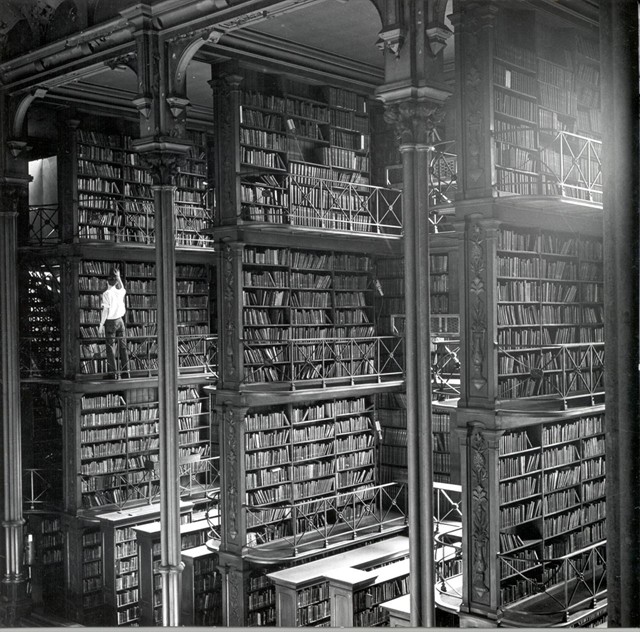

An exceedingly rare snap of august Dobsonist Aloysius Nestingbird trying to locate a particular title among the crammed shelves of the out of print pamphleteer’s teeming archive.

Or possibly the old Cincinnati Library.

In Vegetation And In Awe

I met my antagonist in vegetation and in awe. The vegetation was a patch of scrub and gorse and bracken and furze and phlox and lupins and stunted hollyhocks, behind the towpath that goes along beside the canal, leading to the sea, which in turn leads on to all the major oceans, Indian, Atlantic, Pacific, I can’t remember the names of the others offhand. I was in awe because my antagonist, too, was in awe, and awe has a way of feeding off itself, and increasing exponentially. We made a handshake last for hours.

The stunting of the hollyhocks looked natural, organic, or so it seemed to me. They did not appear to have been pollarded, like the willows by the canal just before the level crossing. The patch of vegetation was equidistant, I would guess, from the level crossing, along the canal in one direction, and the sea, in the other. I could draw you a map, if you wanted me to. I do not think I would have been able to then, in the immediate aftermath of our meeting. My antagonist had a very firm handshake, intimidatingly so, and I was not to be intimidated, so I grasped his hand all the more firmly. I think we were bent on crushing each other’s bones. Neither of us was willing to relinquish the hand of the other. That is why we stood there, in vegetation and awe, like a pair of ninnies, shaking hands for hours.

I had come from the level crossing, he from the sea. His shoes and trouser-cuffs were still wet. It was a humid day. The stunted hollyhocks drooped. The air was thick with flies. In the distance, we could hear the sound of violins. I remember the sense of awe as if it were yesterday, though it was the day before yesterday. I wanted to smoke, and I managed to extricate a cigarette from the packet in my pocket and put it between my lips and take my lighter and ignite the cigarette with deft movements of my left hand. My right was still clutching the right hand of my antagonist in that long, long handshake. For a moment I thought he was going to mirror my actions, for he put his left hand in his pocket, but when he took it out he was holding a boiled sweet. As deft as I, he unwrapped it from its twisted cellophane wrapper and popped it into his mouth. He let fall the wrapper, and it landed upon a lupin. I was disconcerted – I had not had my antagonist down as a litterbug.

He took advantage of my momentary disconcertment to tighten his grip on my hand. I puffed a mouthful of smoke into his face. He blinked once or twice but marshalled himself, but his grip relaxed just a little. We both adjusted our footing, me in my Tyrolean postman’s boots and he in his wet shoes and socks. I think they were quite expensive shoes, though I am no great judge of these matters. I suppose when one lives by the sea one has to pay due attention to one’s footwear.

Neither of us said a word. What would have been the point? We spoke in different tongues, mine that of the interior, his, like Beau Brummell speaking French, that of those accustomed to chewing pebbles and talking next to the sea. Without a pebble, he made do with his boiled sweet. Even if we had shared a language, we were too awestruck to speak. And as our awe grew, so did our antagonism. Would either of us claim victory?

I do not know how many hours had passed when the referee emerged from somewhere behind the clumps of scrub and gorse and bracken and furze and phlox and lupins and stunted hollyhocks. He flicked his ribbon at our hands, still clenched in handshake, and pronounced a tie. We would have to return, to the same place, at the same time, next week. He hinted that there might be television crews eager to cover our confrontation.

Our seconds appeared, and bore us home on palanquins, me to the chalet by the level crossing, he to the sea, the sea. He took my cigarette butt as a memento, and I pocketed his boiled sweet wrapper. At sunset, the patch of vegetation was deserted and undisturbed, as if we had never fought there at all, as if the whole thing had been but a dream.

Birds And Fish

A letter plops on to the mat from Tim Thurn:

Oi, Mr Key! You seem to know an immense amount about birds, yet virtually nothing about fish. Is there any reason for this disparity? If so, I am agog to know, agog I tell you!

Passionately yours,

Tim Thurn

Often with Tim’s letters, I find the best thing to do is to ball them up in my fist, scrunch them a few times, and then deposit them in the waste paper basket. Occasionally, after the scrunching, I drop them directly down a waste chute, if, for example, the waste paper basket is overflowing, as it sometimes is, or, even if space remains in the waste paper basket, I feel impelled to cast the letter as far from me as possible, to obliterate it from my sight.

There is always the possibility, you see, that if I put the scrunched letter into the waste paper basket, I might, while it languishes there, hoick it out and unscrunch it, and unball it up, if that is a phrase, and reread it. Once it has plunged down a waste chute, it is gone forever, of course, or at least its retrieval is made a matter of great complexity, necessitating the involvement of various municipal waste management personnel, who may or may not demand bribes or other favours in order to send one of their number, or some kind of scuttling robot, down into the midden to rummage for Tim’s scrunched letter.

Usually when I discard Tim’s letters so promptly it is because they are annoying. He can be a very exasperating correspondent, and I think he takes a curious pride in being so. I may be wrong on that point, but I don’t think I am. Some people gain a great deal of pleasure from being annoying, and Tim is one of them. I believe he sits there, wherever it is he lives, picturing in his mind’s eye me, huffing and puffing, balling up and then scrunching his latest letter, tossing it into a waste paper basket or down a waste chute, and then going to have a lie down in a darkened room to recover from the mental disturbance he has caused me. I, in my turn, lie there in the dark picturing in my mind’s eye Tim Thurn, chuckling, or chortling, or even guffawing, fatuously, as he imagines my irritation. I impute fatuity to his laughter because this makes it more vivid, and hateful.

Having no idea what Tim looks like, I have to rely on my imagination. Sometimes he is as thin as a rake, angular, and seedy, with unseemly stains on his clothing. At other times he is a tubby kind of fellow, smug and goofy, and seedy, with unseemly stains on his clothing. Once I was so damned livid after reading one of his letters that I decided to consult a graphologist who could, from Tim’s handwriting, fashion a convincing portrait of him, the possession of which would help me visualise his despicable chuckling chortling guffawing fatuity all the more vividly. Unfortunately, Tim confounded me by typing his letters, which rather put paid to my plan.

It would be wrong, however, to think that all of Tim’s missives are equally annoying. Some of them are not annoying at all. Those ones I do not ball up and scrunch and dispose of, but instead lay out flat upon the blotting pad upon my desk, and I reread them, carefully, while composing, in my head, a reply. Such was the case with the one cited above, regarding birds and fish. It was an unexceptionable, vaguely polite, query, and I thought it deserving of a civil response. Of course, I did not want to give anything away. I do not want Tim Thurn, or anybody else for that matter, peering into the innards of my head to see what lurks within. Whether or not I know the first thing about birds or fish is my business, and nobody else’s.

So, though it called for a polite response, I could not answer Tim’s question directly. I would have to craft my reply as carefully as I read and reread the letter – that is, very carefully indeed. Eventually, fuelled by a slurp of Dr Baxter’s Invigorating Brain Syrup, I worked out precisely what to write. First, though, I called on my priest to ascertain how many years I would have to languish in purgatory were I to be less than truthful, or, to put it bluntly, to tell a barefaced lie. Apprised of this information, which seemed not too onerous, I wrote:

Dear Mr Thurn

Thank you for your delightful and not at all annoying letter. I am afraid that, somewhere on its journey between your postbox and my doormat, it was gnawed and nibbled by squirrels or some such small skittering mammals, and much of the content destroyed or rendered illegible. The only surviving text is “an immense amount about birds” and “I am agog to know”. Might I suggest that, grammatically, it would be better to place those phrases in reverse order? That being so, I would happily bombard you with whatever it is you wish to learn about, for example, swifts and swallows and geese and starlings and linnets and partridges and quail and woodpeckers and teal and pratincoles and thrushes and warblers and auks and guillemots and shearwaters and spoonbills and skuas and albatrosses and swans and pigeons and owls and penguins and rooks and crows and dunnocks and pipits and ostriches and cassowaries and grebes and divers and cranes and egrets and sandpipers and cuckoos and parrots and waders and gulls and nightjars and cockatoos and budgerigars and petrels and fulmars and bitterns and herons and moorhens and pelicans and kestrels and cormorants, especially cormorants, and hobbies and kites and rails and eagles and bustards and corncrakes and peahens and plovers and lapwings and wrynecks and curlews and terns and doves and grouse and razorbills and parakeets and hummingbirds and wrens and magpies and jackdaws and, at a push, chickens. Let me know in a bit more detail which birds are of particular interest to you.

Yours carefully,

Mr Key