As the clock tocks towards midnight at the end of the passing year, Miss Dimity Cashew is swept away, she is swept away …

Monthly Archives: December 2013

Old Key’s Almanacke

For several centuries, Old Key’s Almanacke has proved an eerily and unerringly accurate prognostication of significant events due to occur in the next twelvemonth. Here is what lies in store in the Year of Our Lord MMXIV, as predicted by Old Key himself.

January : “Cones” appear at the site of a road closure.

February : Scientists discover a new anagram of Pol Pot.

March : A scribbler publishes a fatuity in The Guardian.

April : Down at the docks, noisome ooze and bilgewater.

May : The De Botton Conundrum is solved, to universal rejoicing.

June : In a hotel, a doctor demands his sausages.

July : Vince Cable stands windswept upon Westminster Bridge.

August : The mighty look on the works of Ozymandias and despair!

September : The crystal ball is cloudy, but we descry something about a footballer and his hamstring.

October : Eggs hatch on a farm.

November : The iFry is launched, a simulacrum of Stephen Fry that witters incessantly and is small enough to be tossed into a wastepaper basket.

December : Jesus Christ returns, his image appearing on a slice of toast.

King Wenceslas

Over at the super soaraway Dabbler there is a traditional Christmas story in Key’s cupboard.

Merry Christmas

A Christmas Carol

Away in a manger, no crib for a bed

The little Lord Jesus lay down his sweet head

And then Tinie Tempah walked into the shed

So I picked up a shovel and bashed in his head.

Tenth Anniversary (XI)

And so our tenth anniversary celebrations come to an end with a piece from earlier this year – Monday 28 January to be precise – purporting to be a diary entry by Captain Nitty from 1954. Here’s to another decade of Hooting Yard! And a merry Christmas to you lot!

Last night it was my turn on duty for the nocturnal pig watch. Brandishing my Alpenstock, I set out across the tarputa as night came crashing down. Some say it is an affectation of mine to use a Swiss stick designed for mountainous terrain when crossing the flat wild bleak desolate windswept tarputa. Perhaps it is, but I never leave home without my Alpenstock these days. Some say, also, “Why are there no twilights any more, no dusks?”, and it is true that nowadays day turns to night in a seeming instant. I cannot account for this, so I do not try to. Conjecture would prove fruitless, I fear, and would make no difference. The fact is, as I grasped hold of my Alpenstock and opened the door, there was daylight, and then I stepped out, and as I pulled the door shut behind me, so it was night.

Night – the time when we must keep watch for pigs. It has not always been so. Years ago, if you can believe it, there was not even a Nocturnal Pig Observatory on the tarputa. Apparently, people used to just turn down the lights in their huts and chalets and lie down in their beds and sleep untroubled sleep. It is hard to credit, is it not? Yet it was so. Where the Nocturnal Pig Observatory now stands, “a triumph of filigree in cement” as it has been described, was nothing more than a stretch of flat wild bleak desolate windswept tarputa, identical to the flat wild bleak desolate windswept tarputa surrounding it on all sides as far as the eye can bear to see.

Hammering on the door with my Alpenstock, I summoned the duty pig observer whose shift was at an end. He handed me the cap and the dockets and flips and flaps and scrippies, unfurled his umbrella, and headed out across the night-black tarputa. I settled myself at the console and adjusted the pig scanner. There was a pong from the oil heater but at least I was warm. Outside the wind was howling and the stars were quivering in the heavens. I thought of Beerpint’s poem “Wobbly Stars”.

And so I gazed. I gazed, now at the monitors, now out through the reinforced plexiglass pigproof window. I saw no pigs. It was a small mercy. But we must snatch at small mercies, and coddle them close, and cherish them. For not all nights are pigless, on the flat wild bleak desolate windswept tarputa.

Tenth Anniversary (X)

Our year-by-year tenth anniversary celebration arrives at 2012. This, you will recall, is the year Mr Key attempted to bash out a thousandish words every day, and very nearly succeeded. Come mid-November, however, a spot of internationl jet-setting threw a spanner in the works. Never mind. Many of the pieces from the first half of the year were collected in the paperback Brute Beauty And Valour And Act, Oh, Air, Pride, Plume, Here Buckle! If you are looking desperately for a last-minute instantly downloadable Christmas gift, do bear in mind that this splendid volume is now available as an ebook from the Amazon Kindle store. Meanwhile, here is a piece from the second half of the year, On Snitby, from Sunday 19 August 2012.

Snitby blubbing on the causeway. A death in the family. The priest is on his way, astride his elegant horse, along the clifftop path. Candles lit in the cottage, and blood on the pillow. The dog is being sick in the gutter. Snitby’s dog, with its corkscrew tail like a pig’s. Call My Bluff on the wireless. Nobody wants to turn it off. Robert Robinson says: cagmag. Nobody is listening. Birds are shrieking in the sky, an impossible blue, not a hint of cloud. Snitby’s tears extinguish his gasper. It is too wet to be relit so he tosses it into the sea. A gull swoops to examine it. The sound of hooves, but it is not the priest, not yet. It will not be the priest at all, today, for the telegram was mistranscribed and he has set off in entirely the wrong direction. He will arrive at Taddy at nightfall and have to be put up at an inn. Here comes the crone with the winding sheet. She has a goitre and clogs. The winding sheet is filthy. Snitby stares at the sea. The gull has flown away into the far distance. It is now a speck. In the cottage, Robert Robinson says: pannicles. There is nobody to hear him, for they have all come out to greet the crone, to kick the dog, to rub its snout in its vomit. It whimpers and scampers to the causeway. Snitby pats its head. A tiny white cloud appears in the sky. A police car screeches to a halt outside the cottage. Snitby scarpers.

Snitby listening to Plastic Ono Band on his iPod.

Snitby sobbing on the jetty. Undone by art. A seaside exhibition of oils by Tarleton. Oil paintings of oily subjects, rigs and slicks and sumps. A terrible beauty. His dog tied to a post outside the galeria. Really an underused seaside civic hall. Snitby overcome with emotion. Here in Taddy where the priest is still holed up in the inn, one or more limbs paralysed. He fell from his elegant horse as it cantered to a halt. A hopeful crone came clutching a winding sheet but he let out a groan and she was sent away. Salt stains on the jetty. Salt in Snitby’s tears. He holds his gasper at arm’s length. Sea sloshes against the wooden posts. Onions on Snitby’s breath. Tarleton dead these many years but still remembered and beloved in Taddy. He was a local boy. Blond and breathless. One leg shorter than the other. Collector of cakestands. Auctioned off. Snitby wanted one but had no cash to speak of. In exile here now and for the future, where the police have no remit. Ancient laws, woolly and medieval, like Snitby himself, after a fashion. In his attic room, the priest’s shutters are shut.

Snitby reading Ruskin’s numbered paragraphs on his Kobo.

Snitby bawling on the pier. The handcuffs chafe. The sergeant has a florid face and a massive moustache. His socks are unwashed and give off a whiff. Klaxons blaring. A pier ventriloquist stuffing his gob with steak and kidney pie while his dummy prates. It is reciting a list of over six hundred birds. Snitby’s face in the sawdust. A couple of teeth loose. Police brutality, but then the sergeant does not suffer fools gladly. Kicks Snitby as an afterthought. Fills out a form with the stub of a pencil. Ten miles along the coast from Taddy, twenty from the causeway. Geographical precision. Pins on a map. The priest an invaluable source of intelligence. One arm now working perfectly, or as near as dammit. Grace abounding. Gruel for his breakfast during Lent. Fish abounding in this resort, but he pushes his plate away with his good hand. The diocese is paying his bill at the inn. Totted up in the innkeeper’s head and nowhere else. Snitby turning to prayer. Mouth full of blood and sawdust. O Lord O Lord why hast Thou forsaken me?

Snitby playing Demented Virtual Needlework on his iPad.

Snitby weeping on the quayside. Tears blurring his vision. He cannot make out the horizon, simply a blank grey blue expanse. Fussing with rosary beads in his pocket. Given up the gaspers for now. Cries of gulls and clanks of tugboats. Foghorns on a clear day. A marching Salvation Army band. Catholicism versus muscular Christianity. It’s an endless battle with no winners. Snitby asked for a nun. He was sure this seaside resort had a convent, right on the harbour. He had his resorts all mixed up. Fifty miles from the causeway on the other side from Taddy. At high speed in a Japanese car with blinking lights and a siren. And motorbike outriders. And two helicopters. Promised a nun on arrival. Not in writing. Snitby’s dog still tied to its post in Taddy. Fawned over by passing widow-women. One will untie it and take it home to a cottage in the woods. It will run away and perish on a railway line beneath a thundering locomotive. The nun will hear about the accident on a nun’s grapevine but decide not to tell Snitby, Snitby in extremis.

Snitby scraping his serial number on his iSlate.

Transportation to shores afar

But the gates of heaven are left ajar

Repent while you can

Repent while you can

O you base and wretched man

O’er the sea to a distant shore

To see your homeland nevermore

Repent while you can

Repent while you can

O you base and wretched man

Snitby jumping overboard.

Tenth Anniversary (IX)

We do not always pay proper attention to the wider world here at Hooting Yard, but on 29 April 2011 we marked the occasion of the royal wedding with a piece about the regal woading. It is reposted here as part of our year-by-year tenth anniversary celebrations.

By rights, several dimblebys should be on hand to guide you through the events of today’s regal woading, but they have been ripp’d untimely from their anchorage, so I am stepping into the breach. Let us be joyful.

Before entering into the state of woaded bliss, the darlings are pulled by elegant horses in procession through the streets of the capital. These streets are lined by flag-waving peasants and other savages, watched over by coppers with clubs “on the ground”, as they say, and, from high buildings, by snipers armed with high-velocity rifles and walkie-talkies. But the mood is rightly joyous. The peasants wave their flags and, as the carriages progress, the darlings, yet unwoaded, wave back, though flagless. The horses have been equipped with tackle that occludes their peripheral vision, to prevent them seeing anything that might make them panic and, in panic, go galloping pell mell, crushing peasants beneath their hooves. Were that to happen, to continue with the woading would be unseemly, and there must be not a smidgen of unseemliness on this day of all days. Hence the horses’ blinkers-tackle.

Within the huge ensteepled and consecrated edifice await the guests and the shamen. None has need of blinkers. The arch-shaman is a fellow with a ragged grey-white beard, as is considered proper for his office. He will perform the rite of regal woading when the darlings are ushered, separately, into the cavernous interior of the edifice. See, there, the trough of woad, and the siphon and funnel and besplattering implement which will be used to woad-besplatter the darlings at the most significant moment of the ceremony.

But first there is much rigmarole, of a kind that cries out for interpretation-by-dimbleby. The arch-shaman, or one of his acolytes, will ascertain that the woading is pure, unalloyed and sullied not by any hint of bewolfenbuttlement. In a modern woading such as this, those watching electrical transmissions may be able to see each individual grey-white hair in the arch-shaman’s beard trembling faintly in the cool air. It is a sight to behold. The horses remain outwith the edifice, stamping their hooves, being fed from nosebags. The peasants and savages too, stay in their pens beside the streets, feeding from crisp-packets. The coppers and snipers stay alert.

Inside there is solemn blathering and the woading itself, and the darlings buss their lips, and a great hosannah of voices is raised in song. Here even a dimbleby might pause, to let it sink in, sound and spectacle without comment. Then, blue with woad, the darlings emerge, upon the steps, to much cheering and clanging of bells, before climbing together into a carriage to be pulled by snack-refreshed horses for the return procession. Somewhere in the teeming masses, a “student” raises a placard of contempt. Before he can be clubbed by a copper or shot by a sniper, he is torn limb from limb by a gaggle of peasants, unnoticed by the larger throng. It is meet that it should be so.

Across the land, jelly and ice cream are gobbled. Huzzah!

Tenth Anniversary (VIII)

We continue our tenth anniversary celebrations wth a potsage [sic] from the year of Our Lord 2010. In the autumn of that year, I embarked on a series of twenty-six alphabetical entries, and this one is C for Canker Worm, which appeared on Sunday 19 September 2010.

Sorely perplexed was I, that I was waking each morning, and had been for months on end, engulfed in a miasma of unutterable spiritual desolation. I sought advice from a quack I encountered on a charabanc outing. He was sitting in the seat next to mine, all wrapped up in a visible aura of wisdom, a sort of pinkish violet haze, and his one good eye seemed, to me, to emit a ray, a ray that could pierce my spiritual innards were he but to train it upon me. I tapped him on the shoulder, so he would turn to face me.

“You look like the kind of fellow who might be able to diagnose the miasma of spiritual desolation within which I tremble, engulfed,” I said, not beating about the bush.

“I am that man,” he replied, and about thirty seconds later he added “You have a canker worm nestling within the very core of your soul, and it is gnawing away at your spiritual vitals.”

“I knew I could rely on you,” I said, possibly a bit too loudly, for elsewhere in the charabanc heads turned and craned to look. I slipped some coinage into the quack’s outstretched palm, settled back in my seat, and shut my eyes. Soon enough we reached the destination of our outing, a ruined fortification of great antiquity and becrumblement, lashed by wind and rain. Tugging my windcheater close about my puny frame, I fairly skipped out of the charabanc into the mud, animated by a sense that, having discovered the cause of my unutterable spiritual desolation, I could now do something about it.

But what was I to do? The canker worm was nestled in my soul, and we still do not know whereabouts within us the soul resides. Indeed, there is a growing body of opinion that we do not have souls at all, that the whole idea is a phantasy, or a metaphor, or just blithering nonsense. Well, I laugh in the face of those who deny the soul’s existence! I may not know precisely where mine is, in brain or heart or spleen or kidney, but I know that it is about the size and shape and colour of a plum tomato. I was told as much by a Magus at a seaside resort, long, long ago.

Traipsing round the ruin, and then on the charabanc journey back – during which there was no sign of the quack, his seat next to mine having been taken by a television chat show host to whom I could not quite put a name, and dare not ask, for he was frowning mightily – I mentally chewed over what I might do about my canker worm. Was there some substance or formula I could ingest that would do me no harm but would blast the little canker worm to perdition? Some potion or preparation, of milk and aniseed and potable gold? Or could I somehow excise it with a pair of ethereal pliers? That might put me at risk of irreversible psychic injury, of course, but was it a price worth paying?

I juggled these and other thoughts until my brain overheated, at which point I went to bed, for it was by now late and dark. While I slept, I had a dream, like Dr King, and when I awoke, I wanted to go and stand on a podium, like Dr King, and declaim the contents of my dream to the gathered masses, declaim it in powerful preacherman language. It took me a few seconds to realise that I had not the magnetic charisma of Dr King to attract the teeming thousands to hear me. The next thought that popped in to my head was to wonder precisely when “Dr King” became the preferred way of referring to the Reverend Martin Luther King, and if this had happened at the same time as it became obligatory for all United States Presidential candidates so to mention “Dr King” in at least one campaign speech, to garner guaranteed applause. Seconds later, the next, and most important thought, occurred to me. For the first time in months, I had woken up without feeling engulfed in a miasma of unutterable spiritual desolation! Quite the contrary. I was filled with vim and gush and pep. I was ready for a large eggy breakfast, and nothing was going to stop me.

Tucking in to my eggs, prepared in accordance with the Blötzmann system (see the appendix to the third handbook in the Lavender Series), I tried to remember my dream, as clearly it provided the clue to my new-found mental and spiritual wellbeing. But I could remember nothing, so after a post-breakfast hike along paths and lanes and canal towpaths, and through a municipal park, I took from its cubby my hat-sized metal cone, plopped it atop my head, aligned my head at the correct angle (see the instructions in Blötzmann’s seventh handbook, Lilac Series) and stared into space, mouth hanging open, dribbling.

Gosh! It soon became apparent that, in the mists of sleep, I had visualised my little canker worm, gnawing its way through my plum tomato-shaped soul, and instead of seeing it as an invader to be repulsed or expunged, I had cosseted it as a pet. I named it Dagobert, and furnished it with a hutch, and pampered it, and took it for walks, insofar as a worm can walk, attached to a lead. The lead was made of ectoplasmic string from a spirit-viola.

The question now was whether I was able to apply these methods to my real, albeit invisible and intangible, spiritual canker worm. Perhaps, if I kept the metal cone on my head beyond the recommended time-limit, thus risking weird head judderings, paralysis, and death, I might be granted the powers to construct Dagobert’s little hutch. After all, I reasoned – ha, reason! – if he was snug in his hutch he would desist from his gnawing, wouldn’t he? I was certain, though on what grounds I knew not, that my plum tomato soul could regenerate sufficiently to repair all the damage caused by the gnawing. But where would I take my little canker worm on its necessary walks? Under the metal cone, my head grew hot and frazzled, and I fell into a swoon…

The following week, I once again boarded the charabanc for an outing, this time to a den of iniquity preserved in quicklime. I sat down next to a different quack, one whose visible aura was purple and golden, and whose spirit-piercing ray projected, not from his eye, but from a star in the centre of his forehead.

“Excuse me,” I said, “But you look like the kind of fellow who might be able to see into my soul and tell me if it is being gnawed at by a little canker worm named Dagobert.”

“I am that man!” he roared in reply, and aimed his ray at me. I waited for him to report his findings. As I waited, the driver lost control of the charabanc and we veered scree scraw off the road and plunged into a ditch. The ditch was riddled with puddles, and each puddle was rife with worms, and some of them were canker worms, and they were legion, and uncountable. But somehow, I could count them, and I did, and I learned that as we flailed, panting and stricken, in the ditch, their number had increased by one. Little Dagobert had gone to join his fellows in their cankerous ditch-puddle of doom, and I was free!

Tenth Anniversary (VII)

Today’s tenth anniversary piece is from Tuesday 24 March 2009, and is entitled The Pavilion By The Shore.

There is a pavilion by the shore. I do not go there any more. I used to visit every day on my clomping horse with its rattling dray, and I’d hammer my fists upon the door of the pavilion set beside the shore, but I do not go there any more. I cannot go there any more.

I used to clomp along the lane lined by beech and larch and plane, but something went wrong in my brain and now I languish in the drain.

I languish in a drainage ditch. I’m smeared with grease and tar and pitch. I’ve lost the use of my lower limbs and at the mercy of vermin’s whims.

All sorts of vermin suck my blood as I lie sprawling in the mud, and others gnaw my skin and bones while I groan my dramatic groans.

Above me, a hot air balloon will be arriving very soon. I’ll be winched up by a length of rope, and washed with disinfectant soap.

The balloonist will sing rousing hymns to cure my withered lower limbs, and we’ll hover in the boundless sky eating a snack of lemon meringue pie.

Then I’ll be dumped back on the lane, a few tweaks putting right my brain, and then I shall return once more to the bright pavilion by the shore.

I’m sure there’s something, before I go, that you are very keen to know. The balloonist’s name – don’t be a clot! It was Tiny Enid, the heroic tot!

Four Generations

Tenth Anniversary (VI)

For our tenth anniversary celebrations, in the run up to Christmas we are reposting an item from each Hooting Yard calendar year. Today, Four Last Songs, which originally appeared on Tuesday 30 September 2008.

Tra La La, The Drainage Ditch is one of the Four Last Songs by elegantly-bouffanted sociopath Lothar Preen. It is, for the majority of critics, the best of the quartet, a brain-numbing racket of melodic astringency with oompah thumping, over which a rich contralto voice sings words torn from the innermost depths of Preen’s creative being. There is also some yodelling, which rarely goes amiss, and reminds us that Preen often claimed to be channelling the spirit of Christopher Plummer in the film version of The Sound Of Music. Preen also claimed to be Swiss, which he patently was not, but that is a matter on which a quietus should be put.

It was long believed that Preen wrote the Four Last Songs in his deathbed, out on a balcony in the mountains, while in the final ravages of tuberculosis. New research shows that in fact he composed these towering pieces on horseback, while riding along various clifftop paths, and it was his horse that was tubercular. Armed with this knowledge, we can make much more sense of the second of the songs, Tra La Lee, Dennis Is Coughing Up Blood, Dennis, of course, being the name of Preen’s horse.

It was long believed, up until a few seconds ago, that Lothar Preen had a horse called Dennis. I believed this myself, but I have just received a message tapped out by a spirit medium which suggests that Preen’s clifftop journey was an elaborate fiction, that he had a goat rather than a horse, that the goat was penned in a goat-pen in a field behind his shack, and that he wrote the Four Last Songs while holed up in the back room of a rough tough seaside tavern while avoiding the bailiffs. This has the ring of truth, as Preen spent the best part of his life being pursued by bailiffs, sometimes across continents. It is not clear if the goat was called Dennis, and it would be interesting to know, but the rapping of the spirit medium ceased as suddenly as it had begun, and now the only sound I can hear is the eerie whistling of the wind in the pines, or possibly the larches. I cannot tell one tree from another. Nor could Lothar Preen, if we accept that the words of the third song, Tra La Loopy Loo, What The Hell Are Those Things Growing In The Orchard?, are autobiographical, as surely they must be.

One curious feature of the Four Last Songs which has exercised the brains of some of our finest musicologists is that there are only three of them. It has been proved, in a breathtakingly pompous essay by Van Der Voo, that Lothar Preen never even considered writing a fourth song in the set, so all those hours and days and weeks and months and years, good God, years, that people like me have spent rummaging in dustbins in Switzerland, hoping against hope to find a “lost” manuscript, have been a complete waste of time. Van Der Voo is a very arrogant man, with suspicious stains upon his bomber jacket, but his argument is watertight, and we must, all of us, bow to his superior wisdom, much as it rankles to do so. That is not the only thing that rankles, my word no!, but if I were to catalogue a full list of my ranklements you would lose patience, I fear, and put me down as a tiresome, complaining git. You would not be wrong.

Tenth Anniversary (V)

For day five of our tenth anniversary celebrations, here is a repost of an item that first appeared on 21 February 2007. You would do well to memorise it, and to chuck it into a lull during the conversation at one of those swish sophisticated cocktail parties you are forever going to (and I am not).

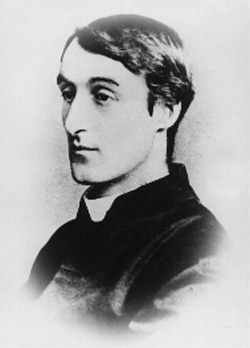

I have been accused of relentlessly alluding to a single extract from the Journals of Gerard Manley Hopkins – the entry where he describes mesmerising a duck – so here is another, equally fascinating, quote:

Tuncks is a good name. Gerard Manley Tuncks. Pook Tuncks.

Tenth Anniversary (IV)

It is day four of our tenth anniversary celebrations. Here is a piece entitled Far, Far Away, originally posted on Monday 4 September 2006. It is one of Mr Key’s own favourites.

Far, far away, there is a galaxy of shattered stars, stars crumpled and curdled and destitute, and there is a planet tucked in among these sorry stars, a tiny pink planet of gas and water and thick foliage, and tucked in among the fronds and creepers and enormous leaves of this foliage lie millions of unhatched eggs, and when they hatch they will hatch millions of magnetic mute blind love monkeys.

I am a crew member of the starship Corrugated Cardboard, heading implacably through deep space towards the galaxy of crumpled stars. Seven years into the voyage, only four of us remain from the original manifest of twenty. There is my captain, o my captain, Pilbrow, a hirsute, raving martinet. We have tied him with cords and confined him to a cupboard, for he has become impossibly dangerous. His spittle is sulphurous, it burns that which it touches, and as he raves, he spits, and he is never not raving, not any more. Ever since we passed through the belt of [illegible] Pilbrow seems no longer human. Being the science officer, I tried to study him, at first. Wearing big protective gloves I transferred flecks of his spittle into my alembic, and ignited my bunsen burners, and peered intently at Pilbrow’s burning spittle, hoping to learn something. I learned nothing. We have travelled far, far beyond the belt of [illegible], and still I have learned nothing. Thus the binding with cords, and thus the cupboard.

Also surviving is Pilbrow Two, a half-size version of my captain, o my captain, made of cardboard, wax and string and animated with life by sparks of something akin to, but not quite, electricity. Pilbrow Two is indubitably alive, a pulsating, rustling, thinking, breathing thing, but it has nothing in common with the raving martinet tied by cords in the cupboard. At the beginning of the voyage, we considered changing its name, we even spent a few days calling it Unpilbrow or Antipilbrow, but neither of these caught on, possibly because Pilbrow Two would boom “My name is Pilbrow Two!” in its deafening voice. Our cardboard, wax and string crewmate has been invaluable in keeping our spirits up. I do not think we would still be heading for the galaxy of crumpled and destitute stars, and for the tiny pink planet, if it were not for his – her? its? – determination. Lumpen would have had us turn back, I am sure of it.

Lumpen is the other survivor. He has been morose and sullen since we ran out of breakfast cereal two years ago, after missing the supply depot on the Planet of Grocery Provisions Epsilon Six where we were due to collect a consignment of Kellogg’s Fruit ‘n’ Fibre. He keeps to his bunk now, head buried in a metalback copy of Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand, his pipe clenched in his teeth, the fumes of his untreated Serbian tobacco hanging in the pseudo-air of the cabin. At least it kills the flies.

The bullet-riddled corpses of our dead crewmates, all sixteen of them, are coffined up and the coffins stacked as a makeshift ping pong table. We cleared a space in the cargo hold by jettisoning some crates of irrelevant rubbish we were meant to be delivering to one of the outlying mini-planets of Hubbardworld. There will be hell to pay if we ever get home, but home seems so far away now, so far, far away. Pilbrow Two is a superb ping pong player, never letting its bat get caught in its string, but I am better. We have played thousands of games over the years, and I have won nearly all of them, sometimes without losing a point. Because it has no heart, Pilbrow Two is not disheartened, and comes to every match with the same valiant perkiness that keeps us plunging ever further through space towards the galaxy of shattered stars.

One afternoon, after a particularly gruelling ping pong match, Pilbrow Two confessed to me that what kept it going, what kept it tweaking the boosters to increase our speed, even at the cost of sending the starship into judders which popped some of the bolts on the pseudo-air-seals, was that it was filled with a burning lust for the as yet unhatched magnetic mute blind love monkeys patiently awaiting birth on the tiny pink planet. This was the first I had heard of them. I became confused, and flung question after question at the half-size cardboard, wax and string simulacrum of my captain, o my captain, but it answered none of them. Instead, it showed me pages of twee love poetry it had been writing, and led me to a corner of the cargo hold where it had hidden a stash of love tokens – mostly things made out of some kind of tin, flowers and lockets and brooches, finicky bittybobs it was going to bestow upon the magnetic mute blind love monkeys once they were born. When I protested that there were, supposedly, millions of these monkeys, Pilbrow Two explained to me, with a winsome sigh, that its love knew no bounds, and nor did its lust, for when it had been programmed back in the lab that gave it life, a stray spark had imbued it with a superabundance of love, lust, and ping pong perkiness.

I wondered whether to share these revelations with Lumpen. But what would be the use? Patting Pilbrow Two on its cardboard head, I picked up my ping pong bat and challenged it to another game, and we played and played and played, as my captain, o my captain, Pilbrow, raved and spat and struggled with his binding cords in his cupboard, we played as Lumpen smoked his pipe and read Ayn Rand for the thousandth time, we played as the starship Corrugated Cardboard hurtled inexorably through space towards the galaxy of stars shattered and stars crumpled, stars curdled and stars destitute, wherein nestled the tiny pink planet of gas and water and thick foliage, wherein nestled millions of unhatched eggs, wherein nestled millions of unhatched magnetic mute blind love monkeys, awaiting their unlikely Romeo, a cardboard, wax and string simulacrum of my captain, o my captain, called Pilbrow Two, bearing poetry and love tokens, far, far away.

Tenth Anniversary (III)

Between now and Christmas, we are celebrating ten years of the Hooting Yard website by reposting an item from each calendar year. Today, The Bilgewater Elegies, a thrilling episode from the annals of Dobson, which first appeared on Tuesday 26 July 2005.

Like the Arctic tern, which is neither from the Arctic, nor a tern, Dobson’s famous Bilgewater Elegies are emphatically not elegies about bilgewater. I’m sorry, I have begun that all wrong. The Arctic tern is from the Arctic, and it is a tern. I was thinking of some other bird of misleading nomenclature, or perhaps not a bird, but an animal, at any rate, which is not what its name indicates. I will try to remember what it was I was thinking of. The central point remains true, however, that the Bilgewater Elegies are not elegies and not about bilgewater, except in passing.

Dobson wrote these magnificent pieces in a wintry month or two while living in a far distant land whence he had gone to escape having to pay his gas bill. Keen students of Dobson’s life know that gas in many forms seems to take on a quite bewildering importance. In one biography, for example, there are three times as many index entries for “gas” as there are for “pamphlets”. Marsh gas, in particular, permeates much of Dobson’s middle years, almost as if it were what he was breathing instead of oxygen. Perhaps it was.

The out-of-print pamphleteer had a deep and abiding reluctance to pay for gas, and often considered living somewhere powered entirely by electricity, or by the wind or the sun, or indeed existing without being dependent upon any source of energy whatsoever. But, as Marigold Chew has noted, rail as Dobson might, he was drawn inexorably to the blue, blue flames of burning gas, a man mesmerised.

I was thinking about guinea pigs, of course, which are not from Guinea and are not pigs. Why I confused them with birds, particularly Arctic terns, is beyond me.

That winter season, then, determined to outwit those who provided him with gas, Dobson decamped to that far distant country, mountainous and cold, remote yet populous, a land of which he knew nothing except the design of its flag. On arrival he discovered that even this minimal knowledge was redundant, as there had been a revolution. The old flag had been ditched, and a new one – pink, black, green – flew from flagpoles wherever he looked. Between the seaport and the chalet where he was to live for two months, Dobson counted at least seven hundred flags.

In the chalet, Dobson closed the traditional butcher’s drapes and placed his canister of calor gas in a cubby hole. Gnawing on a nut, for he was forever nut-gnawing, he considered his surroundings. It was a small chalet, with no hidden chambers, false walls, or concreted-over ancient wells. Dobson was perplexed at the absurd number of metal coat-hangers in the master wardrobe, and the equally numerous drawing-pins in the drawer atop the cubby hole. The cubby hole itself was just the right size for his canister. He was looking forward to burning the portable gas as the evening drew in, but it was still morning, so he curbed his impatience by exploring the outcrop on which the chalet perched. Knowing nothing of geology, and caring less, this took Dobson about five minutes, or about the time it took him to gnaw one of his brazil nuts to nothing. Later in life, of course, Dobson wrote a number of pamphlets on geological topics, as an exercise. Curiously, he never wrote about brazil nuts.

Temporarily out of reach of his gas-creditors, Dobson decided to spend his first afternoon in the chalet on the outcrop in that faraway flag-mad land writing. But he was by turns listless and restless, and irritated that his new domain failed to inspire him. By four o’ clock, having scratched a mere dozen words in his notepad, then torn out the page and set fire to it, he went for a walk. Turning his back on the outcrop, he headed downhill, towards the nearest village, through which his taxi had taken him that morning. He had paid it no attention, for his eyes had been shut, as they often were in taxis. Dobson used such rides for reverie rather than observation.

Marigold Chew once put her hand to a story about Dobson’s walk that day. It was called The Village That Lacked Basic Sanitation, and she refused ever to allow it to be published. All we know for certain is that Dobson returned to the chalet that evening astride a massive, ungainly horse, of chestnut complexion, called Tim. He seems to have been convinced that mice were scurrying uncontrollably about the chalet, and that they would be frightened away by the sight of a big horse. In truth, there were no mice. Dobson had fallen victim to delusional visions because of the high altitude. Nevertheless, the presence of Tim, snorting and stamping his hooves, becalmed the pamphleteer, and the next morning he dragged a wooden table and chair outside the front of the chalet and sat down to compose the Bilgewater Elegies.

Here is a list of buckets of bilgewater I have seen, he wrote, the famous opening words of what was to be his own favourite among his countless pamphlets. He spent whole days in the crisp open air, scribbling away, occasionally filling Tim’s nosebag with horse-food. In the evenings he sat in the chalet staring at the blue glow of burning calor gas. His nights were untroubled by nightmares. Every few days a panting cadet from the insanitary village would deliver a metal tapping machine message from Marigold Chew, keeping Dobson abreast of events at home.

Dobson wrote the final words of the Elegies on a bright day in October. On the same day, there was a counterrevolution in that cold distant country. The pink and black and green flags were torn down and stamped into the muck, swiftly replaced by red and blue and yellow flags. The panting cadet delivered Marigold’s latest message, his cap askew and bloodstains on his sleeves. The look in his eyes told Dobson it was time to flee. He made the cadet promise to look after Tim the massive horse, packed up his things, and headed off for the seaport on foot. The gas canister was empty, and his work was done.

Don’t forget that you can make a donation to the Hooting Yard Fund For Distressed Out Of Print Pamphleteers. Doris X. of Cuxhaven says: “I made a donation and doing so warmed the cockles of my heart!”