There have been no new potsages [sic] for forty-eight hours because my cranial integuments are struggling with a profound and intractable mystery. What has become of L’Oreal’s Light Reflecting Booster Technology? A few years ago they were crowing about it. Now, there is merely a deep and unsettling silence…

Monthly Archives: January 2014

Preposterous Birds

A pair of blue-footed boobies, from Paradise Of Birds:

Victorian Hikes

It is almost impossible to read a memoir or biography of a Victorian writer without coming upon the inevitable walking statistics. Even [John Stuart] Mill, that effeminate “logic-chopping machine”… walked fifteen miles three days before his death at the age of sixty-seven, a modest record compared with [Leslie] Stephen’s grandfather, who celebrated his seventieth birthday by walking twenty-five miles to breakfast, then to his office, and home again the same day. Fifty miles a day was about the average for the “Sunday Tramps” organised by Stephen.

Gertrude Himmelfarb, Victorian Minds (Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1968)

Tiny Enid And The Gigantic Colourful Bewinged Flying Insect

One la-la-la morning, Tiny Enid was limping along the cliffs at the edge of the Big Frightening Sea when, across the sky, zooming directly at her, came a gigantic colourful bewinged flying insect of unknown provenance. Most infants would have screeched in terror and cried for Ma or Pa to rescue them, but of course the plucky fascist tot was not most infants. She raised her arms, as if in terror, to pull the wool over the huge airborne being’s eyes, if it actually had any, and screech she did, but it was a screech not of fright but of blood-curdling menace. It was so terrific a screech that the enormous brightly-coloured mothish type of thing was immediately deafened, playing havoc with its complicated navigational head integuments, and it plummeted forthwith into the broiling waters where, unable to swim, it drowned.

Tiny Enid let fall her arms and patted the pocket wherein she carried her tiny toy Mannlicher-Carcano sniper’s rifle which, in spite of being tiny, and a toy, was a devastatingly effective firearm.

“I am glad I did not have to use my trusty sniper’s rifle to slaughter that curious wing-flapping monster,” she thought, “For it remains fully loaded and I can put the bullets to better use, should I happen later this morning to come upon malefactors and ne’er-do-wells roaming the cliffs.”

As indeed she did, but that is another story for another, more gruesome, time.

Illustration by Vladimir Konashevich, 1923

In Memoriam Pete Seeger

News reaches Mr Key’s waxy ears of the death of Pete Seeger (1919 – 2014), so it seems appropriate to repost this piece from five years ago.

I had a hammer. I hammered in the morning. I hammered in the evening all over this land. I hammered out danger. I hammered out a warning. I hammered out love between my brothers and my sisters all over this land. They should have seen that coming. As I said, before I hammered the love out of them, I hammered out a warning. It was hardly my fault if they thought I was just larking about. Personally, if I had seen one of my siblings roaring towards me at dusk, armed with a hammer, I’d have made a run for it, particularly when it was clear I had been hammering things all day all over this land.

Anyway, I had a good night’s sleep, and the next day I continued hammering. There was not much left to hammer in this land, so I crossed the border. I hammered the fence and the border guards, and then I had a happy day hammering everything that lay in my path in this new country. Bang bang bang, that was me, with the occasional dull thump if I hammered something soft and squishy. I didn’t discriminate. If I saw it, I hammered it, it really was as simple as that.

But then I was fortunate to have such a good hammer. When my hammering was still in the planning stages, it was suggested to me that I should obtain a silver hammer from Maxwell’s. “Pshaw!” I said. I actually said “Pshaw!”, like a character in a bad play from the interwar years. But I was right to do so. Maxwell’s silver hammer was fashionable enough, in its time, but the kind of hammering I intended to do required something sturdier, a real thumper. So I got my hammer from Hubermann’s. I was so pleased with it that I hammered my way out of the shop, and didn’t stop hammering until I got home.

It was the following day that I started to hammer all over this land. Then, the day after that, I hammered my way half way across the neighbouring land. It was much bigger, and much more densely packed with people and things, so I had a lot more hammering to do than in my own land. But eventually I got to the frontier, having hammered pretty much everything in sight. As I nestled down for the night in a border chalet, I inspected my hammer, and was pleased to see that it was almost as good as new. There were a couple of scuff-marks, and quite a lot of blood, but otherwise it looked as if it would serve me well for as long as I continued hammering, all over as many lands as I descended upon, like an angel of death, with my hammer.

The Churn In The Muck

Sag’ mir, wo die Blumen sind? I can scarcely credit that over a quarter of a century has passed since I wrote, illustrated, photocopied, folded, collated, stapled, signed and numbered fifty copies of The Churn In The Muck. Now, this spineless out of print pamphlet will set you back £93. That’s how much a copy is selling for on eBay.

What do you get for your cash? “Vintage Frank Key surrealist writing, in a booklet that contains 4 pages of wallpaper sample and 4 pages of tracing paper. There is a murderous rivalry over an Icelandic fontoon buried at the bottom of a lake. Indefatigable Hungarian detective Bulent Hellbag arrives on the scene to solve the case”, according to Serendipity Bookstore in the far Antipodes. I should point out that, in addition to the wallpaper and tracing paper, there are actually pages of text, too. (I am not sure the blurb makes that quite clear.)

Foiled Heist!

Earlier today I had an errand to do which involved taking a rather large sum of cash to the bank. (My idea of what constitutes a “large sum” may not be yours.) Pansy Cradledew fretted that I might be waylaid by malefactors and ne’er-do-wells, so when I got back – safe and sound – I sent her a reassuring message. I swear on my mother’s life* that every word of this is true.

Just a note to let you know that as I was leaving the bank, several chaps in stocking masks burst in waving firearms and shouting at everyone to get on the floor. I executed a quick tableau vivant of a scene from Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988), and the villains were so awestruck by the verisimilitude of my pose that they were stunned, staring goggle-eyed and dropping their guns. After that it was a simple enough matter to summon Detective Captain Cargpan and his rufty tufty henchmen, who placed them under arrest while I sashayed off to catch the bus.

*NOTA BENE : Ms Cradledew has asked me to point out that my mother died twenty years ago, a fact which she says utterly invalidates my swearage. That may well be so, but I know my onions.

Pods & Their Ilk : The Good News

A number of readers and listeners have written to me on the subject of Hooting Yard podcasts, generally along the lines of “Oi, Mr Key! My life has become barren and empty and devoid of purpose and it is all your fault. Where once I could rely on weekly, or even twice-weekly, new Hooting Yard podcasts, nowadays they only turn up once in a blue moon. What in the name of heaven is going on?”

I ought to explain that I am as bewildered as my correspondents. Once a week, more or less, I go to the Resonance studio and babble into a microphone for half an hour, live on air. How any of what I say eventually finds its way onto the ethereal mews and boulevards of Interwebshire has always been a profound mystery to me.

However, I have good news for all those of you biting your pillows in despair. All episodes of Hooting Yard On The Air are now uploaded, regularly and promptly, to the ResonanceFM Hooting Yard Soundcloud Archive. As I write, there are twenty-eight shows online, with which to siphon out your ears. Turn on, tune in, yelp with glee!

The Brass-Necked Goose

There is a story I remember from my childhood called “The Brass-Necked Goose”. Or rather, I remember the title, but not much of the story itself. As far as I recall it involved a goose that was ordinary in all particulars except that its neck was made of brass. One accepts such improbabilities as a child, as indeed one continues to accept them, when grown, if the spinner of improbable tales is a skilled one.

If, for instance, a Latin American magical realist with a clutch of literary awards under his or her belt introduces into a fat novel a goose with a neck of brass, we might have a moment where we say “pish!” or “pshaw!”, we might even chuck the book across the room into the fireplace, but more likely, given the laurels with which the writer is garlanded, we will accept the goose and read on, dazzled by the author’s inventiveness.

On the other hand, if we are reading a book by some lesser-known writer, and one, say, whose infelicities of style and bone-headed stupidity have already tempted us to chuck the book into the fireplace, and then, as we are growing increasingly exasperated, a goose with a brass neck is introduced for no compelling reason on page 114, then “pish!” or “pshaw!” are going to be the mildest expletives with which we will erupt, accompanied no doubt by curses unsuitable for delicate ears. We will also be likely not only to give in to the temptation and to chuck the book into the fireplace after all, but to ensure that a roaring fire is blazing therein, the better to obliterate this farrago of printed nonsense from our memories.

But as children, we do not care two pins for the literary reputation of the writer, and we are immune to infelicities of style and even to bone-headed stupidity. As children, we are caught up in the story, however improbable, however ill-written. For one thing, we are probably not reading but being read to, by Mama, as we lie tucked snug in bed, our bellies warm with milk, our eyes fixed on the paper stars glued to our bedroom ceiling. When we are told that Ipsy Dipsy, limping along the lane, meets a goose with a brass neck, we simply accept that this is the kind of thing that happens to Ipsy Dipsy, and might even happen to us, if ever we find ourselves walking along a country lane, unlikely as that may be given that we live in a hideous urban sprawl with barely a sprig of greenery to be seen.

I said I could not recall the story, but see! see!, I have remembered Ipsy Dipsy and the lane. Little details reappear in my mind’s eye. I remember Ipsy Dipsy’s pointy red hat, and the callipers on his legs, for Ipsy Dipsy was a cripple, at least at the beginning of the story. I remember the lane, it was a lane like the avenue at Middelharnis painted by Hobbema. Was Ipsy Dipsy Dutch, or Flemish? Was he still wearing the callipers at the story’s end, or had he been able to cast them aside, to throw them happily into a ditch, on account of some magical cure effected by the goose? Did the goose’s magic powers inhere in his brass neck?

As quickly as the memories come shimmering, like the paper stars on the ceiling long ago, so, equally quickly, they fade, like the stars will fade in the heavens. The night sky will be black, and vast, and pitiless. And I will totter about, fumbling in the darkness, aged and exhausted, knowing that there will be no brass-necked goose to save me from extinction.

News O’ Crows

An anti-Catholic crow (and a seagull) have been causing a rumpus at the Vatican. I would like to know what the Jesuits’ position is on crows, ravens, jackdaws, and other birds of menace.

The Lollopers

I lollop. You lollop. He, she, or it lollops. We lollop. You lot lollop. They lollop.

This is the famous opening paragraph of Dobson’s unfinished, unpublished novel The Lollopers. It was one of his very few attempts at fiction, a register for which he was completely unsuited, as he recognised in his magisterial pamphlet A Magisterial Exegesis Of My Resounding Failure As A Novelist, With A Surfeit Of Adjectives And A Ham-fisted Watercolour Plate Of Ida Lupino (out of print). Dobson wrote:

What I wanted to do in The Lollopers was to drill down, down and down, as deeply as anybody could drill, into the very core of lolloping. I thought that if anybody was qualified for the task, it was me, for when I am not trudging or plodding or gadding or sashaying or stalking, I lollop. I have lolloped along canal tow-paths, seaside promenades, important metropolitan boulevards, rustic lanes, and many another haunt of the pedestrian. I have lolloped in all four seasons of the year, in light and dark, in blistering heat and bitter cold. Indeed, in my preliminary sketches for the novel, I planned an entire chapter in which my fictional hero, Dabson, a hugely successful pamphleteer, beloved by millions and the cynosure of millions more, is seen lolloping during a cold snap.

A secondary aim was to really chew my way through the connecting wire, if there is one, between lolloping and lopping. In the domain of trees, for example, lopping is an intrinsic part of pollarding. You cannot pollard, say, a willow, such as the pollarded willows by the canal just before the level crossing in Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1945), without doing a bit of lopping. You might use a woodsman’s axe or a saw of some description, but whatever cutting tool you avail yourself of, lop you will. The question is, between the ramshackle shed from where you collect the axe or saw, and the willow you are set to pollard, and thus lop, is it imperative that you must lollop? Could you, in the throes of hysteria, skip, or even sprint? And if you did not lollop, how would this affect the quality of your lopping, and therefore, with piercingly acute logic, your pollarding? Actually, that appears to be three questions, not one, so the careful reader will spot – perhaps before I did – that I am becoming hopelessly entangled in the thickets of my own creative struggle. I am no longer even clear whether I am writing in the appropriate grammatical tense.

When one considers that lopping might also apply to the lopping off of limbs and – gosh! – whole heads by the armed and armoured henchmen of a particularly vindictive mediaeval baron, is it any surprise that my novel juddered to a halt after that magisterial opening paragraph? It is not.

In the pamphlet Dobson confesses that he shoved the manuscript of The Lollopers into a drawer where, later that year, around the time of Harold Wilson’s resignation as Prime Minister, it was eaten by voracious famished beetles.

The Eggs And Chickens Man

Yesterday, I put all my eggs in one basket and counted my chickens before they’d hatched. These deeds put me in bad odour with the Eggs And Chickens Man who, when he came on his rounds in the afternoon, reprimanded me. He told me in no uncertain terms that I was foolhardy.

“I am sorry, tovarich,” I said, for I lived in the Soviet Union, at least within my head, “I felt strangely compelled to do both those things. I don’t know what came over me.”

He looked at me closely, the expression on his face an admixture of reproach, contempt, pity, disgust, superiority, compassion, bewilderment, nausea, menace, loathing, awe, rancour, spleen, pomposity, sympathy, empathy, and psychopathology. I did not like the way he was absent-mindedly swinging to and fro a huge gleaming razor-sharp butcher’s cleaver.

“Perhaps,” he said eventually, “You are a fool. Like those holy fools with whom your beloved Mother Russia used to swarm.”

“Oh no,” I said, “You’ve got the wrong Russia. I think you’ll find that holy fools were rife in the vast Russian countryside under the Tsar. My own preference is for the Soviet Union, from which such fools were eradicated.”

“Be that as it may,” said the Eggs And Chickens Man, “This is neither Tsarist Russia nor the Soviet Union, and your behaviour was that of a fool, foolish and foolhardy.”

I hate to be reminded that I do not actually live in the Soviet Union. I could feel hot tears welling up.

“Why don’t you pop inside?” I said, “There’s a piping hot samovar full of black tea, far too much for me to drink all by myself.”

He gave the cleaver another, more measured, swing, and I felt a sickening spasm in the bowels.

“I think not,” he said, “I have my rounds to do. I’ll be back tomorrow, and by then I’ll want to see that you’ve redistributed the eggs into several baskets and uncounted the chickens.”

“Uncounted?” I said, “How am I to uncount them, tovarich?”

“Stop calling me tovarich,” he said, “You are perfectly able to button the buttons on your cheap serge jacket, and then to unbutton them. The principle is the same.”

As he walked off along the lane, jauntily swinging the butcher’s cleaver, it occurred to me that I could use what had just happened as material for my work in progress, a novel written strictly according to the precepts of socialist realism. I went indoors, poured a cup of black tea from the samovar, and sat down at my escritoire.

Three hours later, I was still sat there, staring into space, my pen untouched, the paper blank, the black tea stone cold.

A Trip To The Vomitorium

Following the unseemly decision of Penguin Books to publish the maunderings of a has-been pop singer as a “Classic”, we now have the equally risible sight of the British Library paying £100,000 for the collected scribblings and jottings of the hugely untalented writer Hanif Kureishi.

“Kureishi said it was important that it was the British Library that looked after the archive”, apparently – my italics – thus winning this week’s Self-Regarding Wanker Award.

Kureishi : preening

The Rancorous Hobbledehoy

The Rancorous Hobbledehoy is an old folk song collected by the old folk song collector Tick Vange. He was roaming the rustic goat-strewn byways of that splat of land between Fort Hoity and Fort Toity one day when he stopped to lean against a fence and smoke his pipe.

In his memoir of old folk song collecting, Collecting Old Folk Songs In The Vicinity Of Fort Hoity And Fort Toity : A Memoir, Vange wrote:

As I leaned there, against a fence, puffing on my pipe crammed with a goodly swug of moff, o’er the greensward came drifting to my ears, as if from far far away, a haunting melody, played on a pig whistle. It was haunting in the way one is haunted by a grisly ghoul. The hairs on the back of my neck bristled, a shiver ran down my spine, the blood drained from my face, I trembled and I shook, and I piddled in my stylish Italianate faux peasant trousers. What damnable tune was this?

The year was 1937. It was the day after the Hindenburg Disaster, of which Tick Vange knew nothing. His only interests were pipe tobacco and the collection of old folk songs, and he was barely even aware of the existence of airships.

I worked on the assumption, he wrote elsewhere, that anything flying about in the air above my head must be a bird of one sort or another. Having not a jot of interest in ornithology, I could thus safely ignore flying things.

As Vange listened, the melody grew louder and clearer, and he realised the pig whistle was accompanied by singing. The voice was plaintive and grating, like a corncrake with a broken heart. One meets such birds in fables, of course, but this was brute reality.

Peering over the fence into the distance, Vange saw, approaching o’er the greensward, a pair of what he took to be peasants, the one tooting the pig whistle, the other singing. And as they grew closer still, he was able to make out the words.

Here sleeps the rancorous hobbledehoy

On a bed of filthy straw

Oh do not wake the hobbledehoy

Until the crow does caw

The crow will caw and the pigs will snort

The asp will hiss and then in the fort

Our captains brave will come clattering through

Red with the blood of the orphans they slew

All but one who fled and hid

Oh such an ill-tempered kid

They will hunt him down, they will find that boy

They will slay the rancorous hobbledehoy

“I must ask these putative peasants,” thought Tick Vange, steadying himself against the fence, “If their song commemorates an episode in local peasant history. A fort is mentioned, which may be Fort Hoity or Fort Toity. Either fort, or indeed both, might once have witnessed a massacre of the innocents as is alluded to in this haunting plaintive grating song.”

But as the tooter and the singer came ever closer, the old folk song collector saw that, far from being local rustic persons, they were in fact the very picture of metropolitan sophistication, dripping with pearls and dallying with impossibly long cigarette holders. With a start, Vange recognised them as none other than the world-famous music hall variety act Mr Peevish & His Lovely Wife Gwendolyn. What in the name of all the saints in heaven were they doing trudging o’er the greensward?

Tick Vange heaved himself up to his full height, a creditable six-foot-six in his socks, and raised his arm to halt the duo. He was eager to question them closely regarding The Rancorous Hobbledehoy. But they passed him by, without acknowledgement, continuing on their way, tooting and singing. Vange watched them vanish into the distance, in the direction of Fort Hoity, or possibly Fort Toity. He was uncertain of the terrain.

Had he had any interests other than pipe tobacco and the collection of old folk songs, he might have read a newspaper once in a while. Had he read that morning’s edition of Daily Airship Disaster News, he would have learned that among those who perished in the Hindenburg Disaster the day before were world-famous music hall variety stars Mr Peevish & His Lovely Wife Gwendolyn.

Baffling, Brilliant, Brutal, & Hysterically Funny

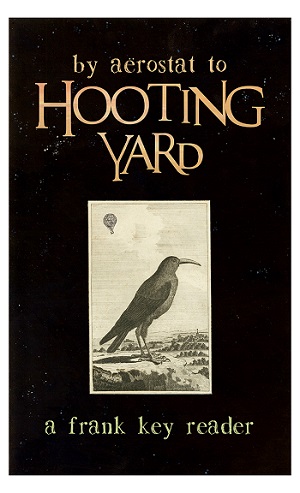

Now here is a treat for you lot. The splendid persons at Dabbler Editions, purveyors of e-books to the e-literate, have launched upon the world an e-anthology of Mr Key’s outpourings. By Aerostat To Hooting Yard : A Frank Key Reader contains 147 stories selected by the estimable Roland Clare, who has also written a scholarly introduction. Truly it may be said he has pored over numberless sweeping paragraphs of majestic prose and has actually managed to work out some of the things going on inside Mr Key’s brainpans.

Now here is a treat for you lot. The splendid persons at Dabbler Editions, purveyors of e-books to the e-literate, have launched upon the world an e-anthology of Mr Key’s outpourings. By Aerostat To Hooting Yard : A Frank Key Reader contains 147 stories selected by the estimable Roland Clare, who has also written a scholarly introduction. Truly it may be said he has pored over numberless sweeping paragraphs of majestic prose and has actually managed to work out some of the things going on inside Mr Key’s brainpans.

According to the Dabbler, the anthology is “baffling, brilliant, brutal, and hysterically funny”. It is also dirt cheap, well within the means of even the most impecunious reader (few, if any, of whom are as impecunious as Mr Key himself). And remember, you do not need a Kindle to read a Kindle e-book. There are plenty of ways to read this earth-shattering and heart-rending tome on any of the electronic contraptions you might have lying about in your hovel. Just ask your nearest computer whizz person.

So the basic idea is that you go and buy the book from amazon.co.uk or amazon.com or amazon.wherever-you-are. You then award it five stars and post a review explaining that it is the most noble effusion of the human spirit since [insert previous noble effusion of your choice]. You then harry and hector everybody you know, and buttonhole strangers in the street, also to buy the book. And on the seventh day you may put your feet up and actually read it.

Come on, readers. If you cannot make this the bestselling e-book of all time, you can at least ensure that Mr Key is in with a chance of winning the mrs joyful prize for rafia work.

N.B. Those of you active on Facecloth and Twitter should strain every sinew to splurge news of the book all over the place. Remember, you will get your reward in heaven.