Monthly Archives: January 2015

The Appian Way

Next time you go for a stroll along the Appian Way, take a pair of shears with you. Then, if you happen to encounter a hairy slave hurrying along, you can seize him and chop off his hair with the shears. When his bare scalp is revealed you will be able to read the secret message tattooed upon his bonce, previously hidden by his luxuriant bouffant. The message will be intended for a distant military general or potentate. Commit it to memory. You are now in possession of important and privileged information, and knowledge is power.

Continue along the Appian Way until you reach the the encampment of the general or the palace of the potentate. Being neither hairy, nor a slave, nobody will suspect you of being the carrier of the secret information. You can use this to your advantage in all sorts of ways.

Next week, in Hints And Tips For Ancient Romans, we will look at how you can influence the prognostications of a haruspex by tampering with the hot entrails of a freshly-slaughtered chicken.

Dobson’s Invitation

In the autumn of his years, Dobson received a letter asking him to contribute to a symposium. Such invitations were rare for the out of print pamphleteer, and he became unreasonably overexcited. Unable to think clearly, he wolfed down his breakfast and went for a brisk walk along the towpath of the old canal, shouting and chucking pebbles at swans. When he arrived home, sopping wet from the torrential downpour, he reread the letter. Apparently, what the sender called his “unique insight” would be welcomed for a symposium on The Importance Of The Cummerbund As A New Romantic Signifier, With Particular Reference To Spandau Ballet.

Dobson had questions, but unfortunately his inamorata Marigold Chew, who he felt sure would know about these things, was off on a week-long gallivant. The pamphleteer had a vague idea what a cummerbund was, but that was about all of the symposium title he understood. He knew a bit about the Romantics, but what was a “New Romantic”? What exactly was meant by a “signifier”? And, most befuddling of all, was there really a ballet troupe resident at Spandau prison in Berlin, and if not, what on earth did the two words, thus conjoined, refer to? These were his questions.

As he pored over the invitation, Dobson felt his excitement bubbling up again. He could barely recall when last he had been invited to anything, let alone an important symposium. Leaving the unanswered questions to waft in the mists of fuddle, he dashed off a letter of acceptance, not forgetting to ask that his bus fare be paid and a cup of tea provided. Then he crashed back out into the rain to buy a stamp at the post office and to plop his reply into a letterbox.

On his way home along one of the less salubrious boulevards of Pointy Town, it occurred to Dobson that the answers to his questions could conceivably be common knowledge among the riffraff. It would not be the first time he discovered that things of which he was wholly ignorant were known by the most wretched and unsightly specimens of the lower orders. A gruesome little twerp, for example, had once vouchsafed to the pamphleteer not only the names of the four Liverpudlian moptops, but also told him which one wore spectacles and was married to an avant-garde Japanese performance artist. This information had proved invaluable when Dobson came to write his pamphlet Several Anagrams Of OO NOOKY, Informed By My Unique Insight Into Popular Culture (out of print).

So it was that the pamphleteer buttonholed a number of hoi polloi in the street, shouting at them about romanticism and signifiers and ballet in German prisons. But by now the torrential rain had grown rainier and more torrential, and all those whose help Dobson sought swept past him, pausing only to curse or spit or kick. When eventually he made it home he was none the wiser.

Dobson sat at his escritoire for hours, pencil poised over a blank sheet of paper. He was at a loss. Then he had a brainwave. He would go to the symposium and extemporize! So long as he included the key words, repeatedly, in whatever he said, he felt sure he could carry it off. Had not Laurence Olivier done the same when performing Shakespeare, babbling nonsense occasionally just to amuse himself and to disconcert the rest of the cast? And after all, this was an academic symposium, when nothing anybody said would make the slightest bit of sense anyway. Dobson tossed his pencil aside and went to slump in an armchair, gazing out of the window at crows in the rain.

The day before the symposium, a further letter arrived from the organisers.

Dear Dobson, it read, I am afraid we are unable to pay your bus fare and cannot provide you with a cup of tea. We are therefore withdrawing your invitation. Toodle pip.

In the spring and summer of his years, a younger Dobson would have parlayed this crushing disappointment into a pamphlet of sweeping paragraphs of majestic prose. Now, he merely slumped at his escritoire, moaning and weeping, for days on end, until Marigold Chew came home.

If you have chuckled slightly while reading this piece, you may wish to make a donation to the Hooting Yard Fund For Distressed Out Of Print Pamphleteers.

The Psychopath-Poacher

A letter plops onto the mat from Tim Thurn:

Ahoy there, Mr Key! I could not help noticing, in your piece yesterday about Satan the little bunny rabbit, that you clearly were at a loss how to bring your trifling bagatelle to a close, hence the introduction, at the close, of a psychopath-poacher who was able to wrap things up in short order. It is not, however, this rather desperate bit of fol-de-rol that bothers me. Of more concern is that nowhere do you acknowledge that you have stolen this character from the much-loved writer of pulp fiction Ned Peasant. In the 1920s and 30s, his tales of rustic violence featuring the psychopath-poacher appeared in dozens of cheap sensational magazines, among them Tales Of Rustic Violence. Thrilling Yarns Of Deranged Peasantry, and Countryside Psychosis Weekly, to name but three. It pains me to accuse you of brazen plagiarism, Mr Key, but sadly that is what I must do. I will be pinning up an accusatory notice to that effect in my local community hub later today. You will not be welcome in my village, should it ever enter your head to pay us a visit. Yours more in sorrow than in anger, for once, Tim Thurn.

Now, Tim will find this hard to believe, but I insist that I have never, ever heard of Ned Peasant nor his pulp writings. I somehow arrived at the figure of the psychopath-poacher independently. Perhaps it was one of those weird and curious happenstances that have no rational explanation, like psychic forewarnings of calamity, or showers of toads, or the existence of Russell Brand.

However, taking my cue from Tim, I did some research, and was delighted to stumble upon a crate full of yellowing dog-eared copies of pulp magazines in one of my cupboards. Sure enough, I found that Ned Peasant had contributed to most if not all of the titles. I read through his stories avidly, in one sitting. They included “The Psychopath-Poacher Slaughters A Badger” (Violent Rustic Antics, Vol. XX, No. 7. July 1922), “The Psychopath-Poacher Slaughters Several Badgers And A Duck” (Bucolic Mayhem, Vol. CXIV, No. 2, February 1928), and “The Psychopath-Poacher Goes Haywire Near A Haystack And Slaughters Hundreds Of Badgers, Several Ducks, And A Vanbrugh Chicken “ (Tales Of Blood-Drenched Enormities In The Countryside, Vol. MMCXVIII, No, 12, Christmas 1934), to name but three.

In my defence, I have to say that my own psychopath-poacher bears scant resemblance to the vivid and timeless fictional character created by Ned Peasant. Nowhere, for example, does Ned’s original gather a sprig of buttercups for his lady-love. Indeed, he does not seem to have a lady-love at all. There is, it is true, a recurring character called Bonkers Maisie, who appears to do various bits of drudgery in a farmyard, but it is never suggested that there is anything between her and the psychopath-poacher save for a shared joy in drinking the still-warm blood of freshly decapitated poultry – see for example “The Psychopath-Poacher And Bonkers Maisie Tamper With The Farmyard Spigot So That From It Spurts The Still-Warm Blood Of Freshly Decapitated Poultry” (The Weekly Digest Of Fictional Farmyard Spigot Tamperings, Vol. MMDCCCXIX, No. 4, Easter 1937).

I have been trying to discover biographical details of Ned Peasant, with little success. One rumour, which must surely be spurious, is that late in life he was engulfed in a miasmic cloud of mysterious gas, shrunk to microscopic size, and after wafting about in the wind for some years was eventually pocketed by Walter Mad, the mad scientist, who injected him into the brain of a mewling infant in a Barking maternity ward at the tail end of the 1950s. Poppycock, no doubt.

Flopsy, Mopsy, And Satan

Once upon a time there were three little bunny rabbits. Their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, and Satan. Flopsy and Mopsy were completely normal bunny rabbits, but Satan, though to all outward appearances he too was a normal bunny rabbit, was in fact the devil incarnate, incarnate in the form of a bunny rabbit. Confident in his overwhelming power to wreak havoc and destruction upon the earth, Satan was playing a long game, biding his time, gambolling in the meadow with Flopsy and Mopsy and doing nothing to let slip his true identity.

It so happened that one day there came clopping by the meadow the itinerant Jesuit Father Ninian Tonguelash, astride his elegant horse. Now, wondrously, the disposition of the buttercups splattered across the meadow matched precisely the disposition of the stars in their constellations in the sky. It was as if the meadow was a mirror image of the night sky, or vice versa. I know nothing of astronomy, so cannot tell you which particular constellations were reproduced by buttercups on the sublunary sphere. But Father Ninian Tonguelash knew all about astronomy, for like all Jesuits he was an intellectual and knew everything there is to know about everything, everything, that is, except the ineffable mystery of Christ Our Lord, and even of that eternal enigma he knew more than most. So as he came clopping past the meadow he could not help but notice the remarkable disposition of the buttercups, and he tugged on the reins of his horse, brought it to a halt, and dismounted.

“Wait here a while, Keith,” he said, popping a sugarlump into the horse’s enormous mouth, “There is something I must investigate.”

Flopsy, Mopsy, and Satan, meanwhile, were gambolling about on the far side of the meadow, thoroughly engrossed in whatever unimaginable vacuity engrosses little bunny rabbits. This was true even of Satan, for he had “gone native”, as it were, while waiting for the time best suited to unleashing pandaemonium upon the world. Not one of the little bunny rabbits paid the least attention to the gaunt figure of Father Ninian Tonguelash, stalking across the meadow, sprinkling each individual buttercup with holy water for purposes only a Jesuit could understand.

But as he came closer, the very air shuddered. The Jesuit sensed the presence of evil, and Satan sensed the presence of rigorous intellectual Roman Catholicism. Father Ninian Tonguelash looked wildly about him, trying to pinpoint the source of all that was foul and unholy. But Satan knew his enemy immediately. He ceased to gambol, and fixed the Jesuit with a piercing gaze of unalloyed hatred. At this critical point, Flopsy’s and Mopsy’s gambollings were so frisky that they collided with the priest’s spindly legs and, in his valiant efforts not to stamp them underfoot, he toppled over.

And then there was a thunderclap. Sudden rain poured down in torrents. Keith the horse swallowed the last of his rapidly dissolving sugarlump. Flopsy and Mopsy gambolled away. And with his head resting on the grass, Father Ninian Tonguelash gazed into the eyes of Satan, and Satan gazed back.

Strange to think that this otherwise ordinary wet afternoon in March could have witnessed the most decisive event in human history. Armageddon could have begun, there and then, in a buttercup-splattered meadow. We do not know, we cannot guess, who would have emerged victorious. All we can say with certainty was that a psychopath-poacher arrived on the scene. From whence he came, we know not, and whither he went, only Keith the horse knows.

The psychopath-poacher levelled his shotgun. First he shot Satan. Then he shot father Ninian Tonguelash. Then he plucked a fistful of buttercups, and trudged across the meadow to where Keith waited patiently. He climbed into the saddle.

“Gee up!” he yelled, and off he galloped on Keith. He had buttercups for his lady-love. In this gorgeous, terrible world, even psychopath-poachers have devoted lady-loves.

Ten Years Ago

Hooting Yard has now been a presence on what Tony Blair and I like to call the Information Superhighway for more than a decade. It is an arresting thought that the site has existed for a longer period of time than that required by a Jesuit to completely brainwash a child. This startling fact prompts two further thoughts, today. First, I am minded to add a slogan to that red rectangle at the top, saying “Dispensing prose to hoi polloi since 2003”. Second, that on a day such as this, when my brain is empty, I can hark back ten years and repost something from so long ago that it is unlikely any of you lot will remember it. I certainly don’t. Exactly ten years ago, on 11 January 2005, this piece appeared under the unwieldy title First Spruce, Now Rusty And Squalid. For this reappearance I have taken the opportunity to insert a few paragraph breaks to make for easier reading. I am sure you can think of a way to show your gratitude for such thoughtfulness.

Consider that fall. One day, you are spry, preening and spruce. Then, knocked sideways, cast down, become rusty and squalid. How does it happen? Is there a moment, a split second, when jauntiness turns to sackcloth and ashes? What would your journal read?

Eleven a.m. : o! such bliss and splendour! How blessed am I to be among the animate and quick.

Eleven o one a.m.: Ach! Does earth harbour a wretch as miserable as I, one who crumbles in despair and is fit only to slither in the muck with the worms?

How are we to make sense of such a catastrophic change? Crystal balls may help seers and soothsayers see into the future, but is it true, as some say, that we can make sense of the present by staring long and intently with our eyes wide open at the surface of a muddy pond over by Bodger’s Spinney? And not any of the ponds there, just one, the most brackish of the ponds, the one which is inky black and fathomless. What will we see on the surface of that pond if we stare at it long enough?

I will tell you. Ignore the flies and mosquitoes and the mutant tadpoles that occasionally disturb the water, and sooner or later, you will be able to discern, dimly at first, but with increasing clarity, the incredible face of the Psychopond Dweller, shimmering, gaunt, bewitched and bewitching, and its expression will reveal to you the meaning of neither past nor future but of the present moment, radical, decisive and, like the cockles and mussels in the old song, alive, alive-oh.

Chickens In Charge

Some time ago, in his Dabbler Diary, Brit wrote about chickens:

Do you ever worry about the scale of chicken slaughter in the world? Sometimes at Asda, contemplating a pack of six chicken thighs, for example, I think, well that’s three chickens that have laid down their meagre little lives right there… And there are so many packs on the shelves. And so many Asdas in the country. Not to mention Tescos and the rest. Then think of all the KFCs across the globe, dishing out bucketfuls of legs and wings 24/7. And of course we cannot exclude my beloved Nando’s’ role in this unimaginable daily massacre.

“Best not to think about it really” he concludes. But I have been thinking about it, for eighteen months now. Not continuously, to the exclusion of any other thoughts in my bonce, but every now and then, every now and then. And whenever I think about it, I find myself thinking, what if the chickens were in charge?

Imagine that a phenomenon beloved of sci-fi writers occurred – a miasmic gas sweeping across the globe, or a befuddling magnetic reversal – and the result was the empowerment of chickens. Perhaps their brains would be transformed and they would become hyperintelligent, or – more terrifyingly – they would remain just as stupid as Werner Herzog thinks they are but grow to monstrous size. Then they would wreak their revenge upon humanity. The unimaginable daily slaughter of chickens at the hands of humankind would become the unimaginable daily slaughter of humans at the talons of chickenkind.

Such a scenario is equally horrifying if we imagine a reversal of our size relative to any small creature, particularly the allegedly “cute” ones. Look carefully at a squirrel. Now ponder how things would be if you were the size of the squirrel and the squirrel the size of you. Do you honestly think it would toss peanuts in your path for you to squirrel away?

This is the stuff of nightmares, and of fat airport bookstall bestsellers and interminable blockbuster film franchises. Revenge Of The Chickens 4, or Squirrel Holocaust 7. Perhaps Brit is right, and it is best not to think about it.

Dabbler Dad

Today would have been my father’s 90th birthday. Over at The Dabbler, I remember him in a version of a piece first posted here three years ago.

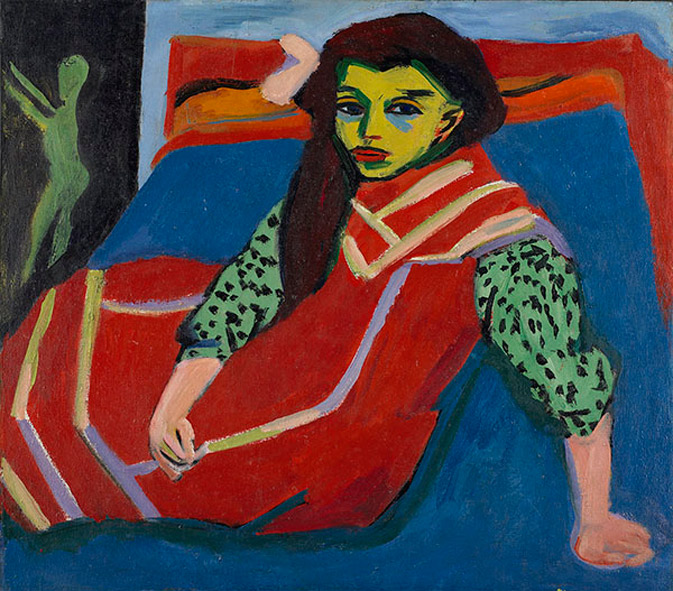

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Friday No. 2

A Soul Above Buttons

My father was an eminent buttonmaker… but I had a soul above buttons… and panted for a liberal profession.

Sylvester Daggerwood, 1795. My thanks to Poppy Nisbet for this important quotation.

Galahad

In the long ago, I was a quiet and well-behaved child, and I rarely got into trouble. There was one occasion, however, when I caused something of a hoo-hah at my primary school. I did not think then, nor do I think now, that I did anything wrong. But I was reprimanded, and my mother was called to take me home, and for the remainder of my time at the school I was considered a “bad egg”. The burning sense of injustice I felt half a century ago has stayed with me, and it is fair to say it has cast a pall over my life.

It so happened that one wet afternoon our teacher Mrs Screech – I think she was related to M. A. Screech, the editor of many Penguin Classics and author of Laughter At The Foot Of The Cross – asked the class to talk about our pets. One by one my little schoolmates stood up and said things like “I have a cat named Tiddles” or “I have a dog called Scamp. He is a collie”.

When it was my turn, I stood up, took a matchbox out of my pocket, and said, “I have brought my pet with me. He is a pismire and his name is Galahad,” and I opened the matchbox and let Galahad skitter about on my desk. For this innocent act, I was reprimanded and taken home and ever after seen as a bad egg and a troublemaker and a wretched, wretched boy. I was told that the word “pismire” was unseemly and that I was frightening the other children by letting a creepy-crawly loose in the classroom. There were other offences, apparently, a long list of them, all bound up in that single incident.

But Galahad was my pet, and he was a pismire. I cannot recall when I discovered that “pismire” was an archaic term for “ant”, but as soon as I heard it I knew it was suitable for Galahad. He was fully deserving of two syllables. He was a valiant little ant, and a loyal one. Every night, before I went to bed, I would take him out of the matchbox and put him in the garden so he could run about with all the other ants, and when I went to collect him in the morning he was always there, with his teeming hundreds or even thousands of fellows, and I would pick him up and put him in his matchbox and plop it into my pocket. It may be that Galahad was not precisely the same ant every day, though it was hard to tell, and I tried not to bother my little head about it. If he was the same ant, as I like to think, then he is extraordinarily long-lived, for an ant, as I still have him in a matchbox in my pocket as I write these words, fifty years after the burning injustice which has cast a pall over my life. It is a pall only lifted by Galahad himself. During our long and intense conversations, conducted in the language of ants, punctuated by screeching, he offers me solace and consolation. He is my pismire pal.

The Clappers

In a comment on Peewit Patrol, yesterday, Dave asks about my use of the phrase “running like the clappers”. The clappers referred to are those of bells, which strike the inner surface of the bell to create that clang we know and love and occasionally stuff cotton wool in our ears to muffle.

If it is argued that the clappers of bells do not run, nor trot, nor scamper, all I can offer in my defence is that the phrase, meaning “to go very fast”, seems to have originated with Royal Air Force public school chaps during the second world war. The OED cites Eric Partridge’s (not Peewit’s, note) A Dictionary of Forces’ Slang 1939-45 (Secker & Warburg 1948). Further citations suggest that it can rain like the clappers, and that one can both surrender and go to work like the clappers, so running towards a spinney for an initiation ceremony in the moonlight seems equally viable.

It should be noted that the bells the clappers of which go so very fast are specified by Partridge (not Peewit) as the bells of hell. It so happens that Dobson, the titanic out of print pamphleteer of the last century, devoted one of his pamphlets to this very subject. Fanatical Hooting Yardists may recall this piece, originally posted five long years ago, in the dying days of the Brown administration:

The bells of hell do not ring, says Theophrastus Dogend, they clank and clunk, eternally, awfully, deafeningly. This is because they are battered and broken, with great cracks and fissures. He adds that they are covered in mould, of stinking greeny-grey.

There are no bells in hell, we are told by Pilupus Taxifor. He says the clanks and clunks are the din of infernal machinery, engines of havoc, designed to torment the damned. If there be stinking mould upon the machines he does not say.

While Optrex Gibbus maintains there are precisely ten thousand bells in hell, each of them numbered, each in its own belfry, and they are rung by sinners, in expiation, the bell-pulls in the form of vipers, which bite the sinners’ hands and wrists each time they peal their designated bell.

Dobson’s pamphlet Hell, Its Bells (out of print) is an attempt to untangle the contradictions in these authorities, each of which, he contends, has at least a grain of truth. Are there bells in hell, he asks, or are there not? If there are, do they ring or do they clank? And clunk? Are there ten thousand bells, or fewer, or more, even an infinity of bells, just as there is an infinity of pits and dungeons and oubliettes in which the damned languish forever?

The pamphleteer’s research for this paper, which he read aloud at a meeting of the Sawdust Bridge Platform Debating Initiative on the tenth of April 1954, led him up some pretty horrible pathways, pathways more abhorrent even than the one that runs parallel to the disgusting canal wherein the vomit of generations has collected. Why it is that drunks and those with stomach disorders have habitually seen fit to throw up their guts in a canal basin at the end of a long and twisting lane far from any clinics and hostelries is a mystery Dobson never investigated, so far as we know. But he was spellbound by the bells of hell, upon which, he believed, so much, so very very much, hinged. It is a pity he never got round to writing the follow-up pamphlet, Hell, Its Bells, And All That Hinges Upon Them, With Lots Of Details, a work which exists only in the form of illegible scribblings in a notebook half of which is burned and the remaining half smeared with a stinking greeny-grey goo, which might be mould scraped from the bells of hell, but might on the other hand just be the sort of goo that Dobson managed to attract to himself, in his wanderings, God knows how.

Hooting Yard Encyclopaedia topics addressed : Hell, bells, goo.

Peewit Patrol

In spite of the example set by my older siblings, I was, as a child, reluctant to join an organised group such as the Boy Scouts or the Woodcraft Folk or the Young Pioneers or the Kibbo Kift. I kept myself to myself, content to lollop about in self-imposed solitude. All that changed, however, on the day when I was eight years old and I received an invitation to join Peewit Patrol.

I had never heard of this little fraternity, so I was intrigued. Intriguing, too, was the invitation itself, which was delivered to my bedroom windowsill in the beak of a bird I supposed was a peewit. It took the form of a folded sheet of paper which, when extracted from the bird’s beak and unfolded, revealed a message which looked as if it had been scribbled in blood. “Come to the spinney at midnight,” it read, “Where you will be initiated into Peewit Patrol”. It was unsigned.

That night, I went up to bed at my usual time and pretended to be asleep. Excited and alert, I listened out for the sounds of my siblings and parents retiring for the night. When all was still, I crept out of bed, fashioned a rope ladder from my bedsheets, and let myself out through the window. The spinney was out on the edge of our bucolic – our idyllic – village, and I ran like the clappers to get there before midnight struck.

I was puffed out when I arrived, and for a moment I thought someone had played a trick on me, as the spinney seemed to be deserted. But then, one by one, from behind clumps of trees, appeared several children, a dozen or so. At least, I thought they were children, they were all about my size, but I did not recognise any of them because their faces were concealed. Each wore a painted papier-mâché helmet in the shape of a peewit’s head, roughly double the size of their own heads. From the neck down, they were dressed conventionally, save for a tabard and a sash. I gawped.

One now stepped forward and greeted me. He explained that I was to be initiated into Peewit Patrol, a great honour, but one which I must keep secret. A bonfire was lit, and the children began to prance and caper in a circle around it, uttering shrill cries which may have been imitative of a peewit’s call. I was taken by the hand and pulled into the ring and did my best to prance and caper and shriek like the others. When we were all at the point of exhaustion, at a signal we stopped still. The circle regrouped, with me now at the centre.

The child – if it was a child – who had first greeted me now made a long and frankly incoherent announcement. The gist of it, I was able to gather, was that I was to be welcomed into the fraternity of Peewit Patrol and I must swear to serve it with all my gumption. A bumper bottle of Squelcho! – a sort of fizzy pop – was opened and passed around, and each one took a swig before it was passed to me. I swigged, and swore. And then the tabard and the sash were draped over me, and the painted papier-mâché peewit helmet was placed upon my head. I was a member of Peewit Patrol!

And there and then I set off on my first patrol of the village perimeter, in the moonlight, sworn to protect the village from harm. We were each armed with a stick gathered from the spinney floor, and we marched slowly, keeping a watchful lookout through the apertures in our helmets. Occasionally one or other of my companions would make the shrill peewit cry.

It was an exquisite thrill for me, who had been so solitary, to feel a sense of belonging – belonging to a secret, illicit band, but one which acted for the good of the village, unknown to the adult villagers. And the thrill was never more exquisite than on those nights when we came upon a vagrant or a beggar or somebody who looked a bit funny, and we swooped down upon them in a terrible flock, beating them savagely with our sticks, and, when they were crumpled and helpless on the ground, we fell upon them, pecking at them in a frenzy with the razorblades embedded in our papier-mâché beaks, saving the village from outsiders who would do us harm. Happy days!

Death Room Decoration

In her letter yesterday, Poppy Nisbet mentioned the decoration of the “Zeitgeist” Death Room, consisting in part of portrait paintings (by Marjorie Monroe) “of subjects who all looked like characters from Agatha Christie” from which “the faces [were] cut out and the rest of the image left intact”. Ms Nisbet has now provided photographic evidence of what she is talking about, so you lot can better appreciate the spookiness.

Left : intact portrait, Right : wrecked portrait.

Crow Windows : An Addendum

On Thursday I remarked that it was hard to imagine a window made out of crows. Not for the first time, I was wrong – astonishingly so, given that ornithology is involved. But wrong nonetheless, as this letter from Poppy Nisbet makes clear. It plopped through the post all the way from the eastern United States:

In the long ago I occasionally worked on local theatrical extravaganzas, my favorite being “Zeitgeist”, an excruciating interpretation of Human Life from beginning to end. We, the perpetrators of this cultural maelstrom, took over the very small town hall in a very small town nearby. The building had a central front door and hallway flanked by two minuscule offices and leading to a large open room with a stage at the far end. As a preface to the main event onstage we made the offices into a birth room and a death room. It is the death room that requires description.

The house I now live in had belonged to artists for a long time and the higgledy-piggledy remains of their art lives were still in the barn studio when I moved here. One of the artists was a portrait painter of subjects who all looked like characters from Agatha Christie. The studio was overflowing with petrified tubes of oil paint, bristle-free brushes, canvas stretchers, human bones, broken glass and empty frames, my favorite relics being paintings with the faces cut out and the rest of the image left intact. As a backdrop for the death room these edited portraits were hung on the walls above dead leaves piled high, so deep that people could only wade through them with difficulty. The resultant noise was full of memories.

The room had a dilemma that demanded solving, a large window facing the parking lot. We felt that the evening trajectories of headlights would spoil the mood on the night of the performance so we cut silhouettes of flying crows out of a piece of black foam-core board and fitted it over the glass. A sheer curtain was hung over this on the inside, making the window amendments invisible in the general murk.

The headlights swept through the birds like a fog beacon, flaring up for a moment and projecting distorted avian outlines onto the folds of the curtain and the floating dust of the leaves. It left a surging impression of flight that was surprisingly spooky. Even now, whenever I see crows I remember the motion of light in black bird shapes filling up a window.