Last week I had an extraordinary stroke of good fortune. Ever since the afternoon of Friday last, I have been engulfed in a flood of memories, and I am discombobulated and a-dither, quite unlike my usual self.

I was wandering the streets of Pointy Town, somewhat aimlessly, and as I turned a particular corner I felt compelled - there is no other word for it - to head off down a dark, narrow alleyway where lurked a strange little shop. Do you remember the scene towards the end of Random Harvest (1942), where Charles Rainier, played by Ronald Colman, turns down a side-street to go to a tobacconist, and then wonders how he knew it was there, this being a town he has never knowingly visited before, and how his consternation is the spur to his gradual recollection of the life that a traffic accident has wiped from his memory, leading, within a few minutes of film-time, to the tear-stained scene where he and Paula (Greer Garson) are reunited at the gates of their idyllic country cottage? Well, as I entered the shop in that Pointy Town alleyway, I had a very similar jolt to my memory, although I am not a veteran of the First World War whose shell shock had led to total amnesia and a reluctance to speak, like Charles Rainier. Readers who have no idea what I am gabbling on about should take steps to see this magnificent film at the earliest opportunity. I guarantee that even those with the flintiest of hearts will be sobbing copiously by the end, not that Hooting Yard readers tend to be flinty-hearted, as a general rule, according to the latest readership profiles gathered by Fatima Gilliblat and her team of wastrels.

The shop into which I tottered, having tripped on a thing discarded in the alleyway, was not a tobacconist. It was called, I noted, This Vale Of Tears, and its unexpectedly neon-bright interior contained a heteroclite jumble of items for sale. I can only call them odds and ends. Battered biscuit tins, dishcloths, iron utensils of no apparent utility, bags full of swan feathers, rubber inhaling tubes, dog-eared snapshots of goats, pigs, and barnyard animals in general, buckets and pails, packets of cupcake mixture, fawn overslings from a stage production of Tap Or Spigot?, fruit made out of wax, fold-out wiring diagrams, wiring, cheesecloth, pastry cases, bound copies of The Propeller, abandoned and in some cases broken sandwich boards, a stuffed crow, litmus paper, human hair braided into rope for ships, surgery-ready canisters, pin cushions, Toc H lamps, fahrenheit converters, big forks, rotating wooden cubes on a spindle, frozen blobs, an information poster showing the correct pronunciation of “yoghurt” (that is, “yo-hoort”), tassels, baubles and bells, some of them enormous bells from a famous foundry, annals of jurisprudence, kitchen whisks, repair kits for the irreparable, teaspoons, marzipan, clock springs, grease in balls, a thanatophore, a marble bust of the head of Ringo Starr, lanterns, rattles, fripperies, saws, starched white butchers' curtains, and there, in among it all, still in its dust-caked packaging, but otherwise pristine, an original series Ogsby's Steering Panel.

Were you lucky enough, when you were a tiny tot, to receive an Ogsby's Steering Panel as a birthday gift? I was. I still remember with absolute clarity waking on the icy cold morning of my tenth birthday, and finding at the foot of my bed a rectangular object wrapped in old newspaper, on which either my father or my mother had scribbled in crayon “Happy Birthday To Our Ten-Year-Old”. I was a dutiful and pious child, so before tearing the package open I repaired to the bathroom to brush my teeth and plunge my head into a sink full of icy water, and then I went downstairs to find my parents.

My mother was in the garden slaughtering insects. I thanked her for my gift and asked where my father was so I could thank him too. She gave me a woebegone look and patted me on the head, mussing my hair in which icicles were beginning to form.

“I am afraid your father had to take the dawn train to a secret military establishment at an undisclosed coastal location - towering cliffs, monstrous waves, shingle - where he will be cooped up for the next six months helping to devise counter-intelligence techniques for use against an enemy so powerful, so ruthless, so fiendish, that it beggars belief,” said my mother, and she tapped the side of her nose, indicating that this startling news was to be kept under my hat, had I but a hat to keep it under.

“Gosh!” I replied, “So papa is not, as he appears to all and sundry, a simple village potato shop person. That is but a cover for his real work, which is of national - no, international - importance. Well I never.”

“It is indeed so,” said my mother, “And as it is your birthday I am going to make a present to you of a hat, and you must promise like the dutiful and pious child you are to keep this world-shattering revelation underneath it until you reach your majority.”

“I will do so, mama,” I promised. Her mention of a present recalled my mind to the rectangular package at the foot of the bed. It seemed unlikely that it contained a hat. It was as if my mother read my thoughts.

“The hat is an extra gift,” she said, “For your proper present is the one in the rectangular newspaper-wrapped package at the foot of your bed. Go and open it now and leave me to my slaughter of aphids.”

I ran upstairs and tore open the rectangular newspaper-wrapped package at the foot of my bed. Is it possible to convey to you the sheer joy with which my entire being was convulsed when I saw that I had been given an original series Ogsby's Steering Panel? There it was, new and gleaming, with its little knobs and levers, and the red bakelite prong on one side and the rubber speaking funnel on the other, the braille-like raised round nodes next to the hooter, the metal snags, the clip-on flaps, and so many, many dials!

I think I played with it constantly for the next three hours, until the terrible moment when my father suddenly crashed through the door of my room, ashen-faced and trembling, and tore the original series Ogsby's Steering Panel from my puny little hands.

“I have had to jet back here suddenly, son,” he said, in a voice broken by strain, “Our powerful, ruthless, and fiendish enemy is within minutes of unleashing a plot so intricate, so tangled, just so damned bonkers that the very future of the globe is in direst peril. Only by dismantling your new original series Ogsby's Steering Panel and using the parts for our top secret counter-attack machine will the world be saved, to guarantee that children like you have a future free from fear of all that is fiendish. I'm sure you understand.”

And he was gone, and I was left alone on the floor of my room, dutiful and pious, and I never saw my birthday gift again. Oh yes, the world was saved, the powerful and ruthless and fiendish enemy was foiled, my heroic father resumed his humble potato shop person persona, and my mother eradicated all insect life from our domain, but I always felt a sense of unbearable loss, until last week, when I stumbled upon an original series Ogsby's Steering Panel hidden behind an array of papier maché dustbin lids in This Vale Of Tears, in that gloomy alley in Pointy Town, and the long, insufferable, melancholy years were swept away, and I was ten again, with icicles in my hair.

A letter, with enclosures, arrives from that scalliwag Max Décharné.

Given the heated freedom-of-speech debates in the papers during the last few weeks, he writes, I thought you ought to see this shocking photo of a futile lone outpost of wrongheaded anti-Hooting Yard protesters, who appear to have barricaded themselves into an unattractive lock-up garage and are demanding Dobson's head on a platter (or near offer…). Have they no shame?

Meanwhile, here's a photo of Robert Fripp's sister, Patricia, being sawn in three by a magician. All in a day's work…

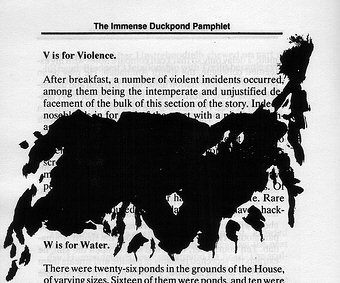

And so we reach the nineteenth episode in the serial story the world has clutched to its bosom, The Immense Duckpond Pamphlet

In the Room of Distressed Wooden Bitterns, Euwige cracked open another bottle of dandelion and burdock. Celebrations were in order. She and Detective Captain Unstrebnodtalb had not met for fifteen years, since that time in the aeroplane hangar.

Then, Euwige had just returned from Slot, where she had torn some paper, arched her back like a cat, and stood next to a dam. Unstrebnodtalb was at the hangar to meet her, brandishing a trumpet. At this stage in his career, he looked not unlike a Hungarian fairground proprietor. He wore spats. He had gabbled at Euwige importunately, but his command of human languages was not good, and she had difficulty understanding him. Eventually, she had snatched the trumpet from him and beat him over the head with it repeatedly, stopping him in mid-gabble. Then she pushed him into a cart and rattled off to the House.

Now, after all those years, they had a lot to catch up on. The walls of the Room shook as Unstrebnodtalb told his anecdotes in booming, cataclysmic roars. Jubble shoved putty into his ears to dull the racket. But Euwige seemed unperturbed, regularly refilling their tin mugs and badgering the Detective Captain with questions. What had happened to his spats? Was it true that he had arrested the notorious strangler Babinsky, and shaved off his bristly side-whiskers? Was his brain hot? Did moths fly about his head? Did he make crunching noises? Why had he not come sooner?

Unstrebnodtalb, flicking gnats and hornets away from his head, smashed up the empty dandelion and burdock bottles with a single thwack from his huge and hairy fists. He had his own question for Euwige. What had become of his trusty assistant Aminadab?