A Note on Pigs

“From the grossness of his feeding, from the large amount of aliment he consumes, his gluttonous way of eating it, from his slothful habits, laziness, and indulgence in sleep, the pig is particularly liable to disease, and especially indigestion, heartburn and affections of the skin,” wrote Isaballa Beeton in her Book Of Household Management (1861), continuing to note “To counteract the consequence of a violation of the physical laws, a powerful monitor in the brain of a pig teaches him to seek for relief and medicine.”

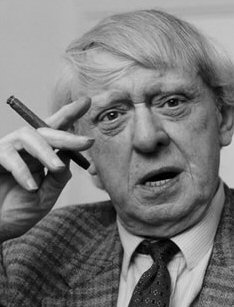

When he read these words, exactly one hundred years after their publication, a firestorm convulsed Dobson's brain. He had never given much thought to pigs, but now he became obsessed with discovering the precise nature of that “powerful monitor”. If he could harness its power, who knew what wonders might be achieved?

“I am going to devote the rest of my life to what Mrs Beeton calls the ‘powerful monitor in the brain of a pig’” he announced to Marigold Chew one rainy Wednesday morning in 1961, as they walked across the sodden fields towards the old kiosk for their breakfast crackers, “And I will harness it!” he added, shouting.

“You are going to become half man, half pig?” asked Marigold Chew.

“Of course not,” countered the out of print pamphleteer, and went into one of his sulks.

Marigold Chew assumed that this latest fad of Dobson's would fizzle out within hours or days, and was disconcerted a week later to find dozens of pigs lolling around in the back garden. Standing in their midst was Dobson, holding a large metal cone from which wires and other gubbins trailed.

“Where did all these pigs come from and what's that your holding?” asked Marigold Chew.

“I borrowed the pigs from Old Farmer Geistigenacht, and this is a rudimentary brain scanning machine with which I intend to locate the powerful monitor contained in the brain of each and every pig. Isn't that obvious?”

So saying, Dobson approached the pig nearest him, a plump and dappled creature of I know not what breed of hog, and tried to affix one of the lengths of trailing wire to its head. Being a butterfingers, the pamphleteer-turned-pigman failed at even his umpteenth attempt, for the pig defied all attempts to be forcibly attached to the metal cone. Marigold Chew did not offer to help, instead returning to the house to make a cup of cocoa and to play a recording by the Bodger's Spinney Dance Orchestra at deafening volume to drown out the grunting and squealing noises from the garden.

Dobson came in about half an hour later, fractious and dishevelled, his hair in a frenzy and his cone dented.

“The monitors in the brains of these pigs,” he said, “Are more powerful than Mrs Beeton realised. Even though my splendid metal cone has been dented, and its trailing wires and other gubbins frayed, rent, or in some cases detached, initial readings indicate to me that extremely interesting vibrations are being emitted, especially by the plumpest and most dappled pigs. Not just vibrations, but rays!”

He took a hammer from a cupboard and began beating out the dents in the cone.

“Readings?” asked Marigold Chew.

Dobson stopped hammering and flailed a sheaf of papers at her. There were dozens of sheets - one for each pig - and each was covered with scribbled writing, graphs, diagrams, and lists of numbers.

“The human mind,” declaimed Dobson, “Cannot correlate this stream of pig-related data. That is why I intend to harness their powerful brain monitors for my own purposes. Future editions of Mrs Beeton's Book Of Household Management will be incomplete without my majestic addendum, which will probably run to twice the length of the book itself. When I have beaten out every last dent in this metal cone, I shall place it atop my own head, sit down at my escritoire, and set to work on a piece of writing that will outshine all my other pamphlets, and will shake the world!”

As Dobson picked up the hammer again, a rustic urchin appeared in the doorway.

“I've been sent by Old Farmer Geistigenacht,” he said, in an adenoidal bleat, “He says he wants all his pigs back by dusk, for they sleep easy in their sty and out in the open of your garden they will have nightmares. If you've ever seen dozens of pigs in the grip of night terrors, you'll do as he says.”

The boy led the pigs through the house out into the lane and led them gently home. Dobson sat with the cone on his head, sharpening his pencil. But the fire had gone out of him, and he scrawled only a few sad and broken words before slumping on to the floor, where Marigold Chew found him in the small hours of the morning, dreaming of pigs, and in his dreams the pigs were happy, they were oh so happy.

A pig running away from Dobson's brain scanner cone