We had been awake for eleven nights. Cloth had been wound around the jugs, and a fresh coat of varnish applied to the trapdoors. The hooks were blue. Their blue was the blue of farmyards, oilrigs, malfeasance. I broke the engineer's pencil in half. He was furious. His fists met mine. There was something gruesome stuck underneath the lantern. I hurled it over the gunwale, to the cheers of my crewmates. Then they turned on me, one by one: Blubb with his yellow tooth; Slubb with his bottle of vinegar; Flubb with the rhinoceros mask & hideous trousers. I fled. Later that night, the Carpathians in my sight, a small shard of bitumen became embedded in the rafters of my cabin. The time had come to throw the ledgers into the sea. With irrational joy, I glared up at the stacks of sailcloth, and my eyes ran with tears. Would I taste potatoes again?

I - So was a tempest loosed upon the city, and its very fabric uprooted from the mud. Whirling and howling, the city was dispersed upon the firmament, coming to rest none knew where. And the mud spawned all manner of noisome pests, squirming and wriggling to escape the gigantic puddles which were left in the wake of the storm. These were not puddles of water, no, nor of any liquid known to the human mind. And then my eyes saw, standing fiery on a wooden plinth ringed by scum-pools, the obscene figure of Winckelmann. In his left hand he brandished aloft a scrap of burning linoleum. His right hand was made into a fist. As, dribbling, I watched, the fist was slowly opened to reveal a….. I cannot say. I do not know. For just at the moment my peering, watery eyes would have seen that… that thing, I was startled by a toad, which leapt up at my face, and thwacked me on the forehead, leaving an imprint which remains there to this day, like a brand.

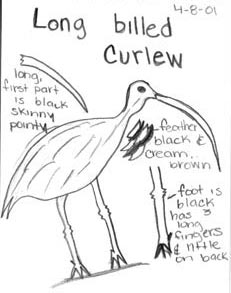

II - The man with the toad-mark flapped his shattered wings. In vain, in vain. Perched on the rock, beaten by harsh winds, encrusted with seaweed, sightless, he was of a sudden assaulted by a voice, roaring at him across a thousand continents. “Man with the Mark of the Toad! Know ye the Song of the Boll Weevils? Aye? Then sing, damn ye, sing!” Whence came that monstrous voice? What hideous nursery had cosseted its owner, what kitchen fed it? “Man with the Mark of the Toad!” it screamed again, pulverizing universes, “Hare ye to me now, leave your drab rock! Shed your cracked wings! Sprout fins, smack the boiling sea with your flippers, come to me! I hold in my gnarled, gnarled hands many gifts for you! I hold anconeal bowls! I hold strangled curlews! I hold pods and gum and pitchblende! Spring forward now! Go from your dour perch! I hold magnification instruments, Coddington lenses, and towels for you! I hold pigeons' blood, crayons and isinglass! The crayons are of colours no human eye should ever contemplate! The isinglass gleams in a charming handmade jar! The jar has your mark upon it, Man with the Mark of the Toad! Come….” There were hours upon hours of this wretched gibberish, enough to make an ant die. The man with the toad-mark beat his useless wings against the wind and turned his head away. His brow was crawling with gnats. The gnats had come a long way, from barely imaginable puddles of slop where once a city had stood. The City of Gnats.

III - Winckelmann strode importantly through the boulevards of the walled city. He chucked trinkets and baubles to beggars and cripples, holding a vermilion cravat over his nose as he did so. Worms slithered up his dainty anklets, only to be torn away by scrofula-ridden flunkies. Imposing but haphazard, Winckelmann relied upon his most trusted attendant to lead him in the right direction. These boulevards all looked alike to him. He could be going anywhere, were it not for Sigismundo's genius. As a factotum, he was a treasure. Save for his inexplicable habit of pissing on coinage, Sigismundo was faultless. In this warren of pestilent streets, he knew precisely what to do. Turn right by the trough; ignore the screeching placardists; beat the pedlars insensible with their own clubs; smartly avoid the motorbikes. Before long, Winckelmann and his retinue stood in the courtyard of the Impossibly Huge Building. The stink was repellent, but Winckelmann knew etiquette if he knew nothing else. With an effort, he removed the cravat from his nose and, at a signal from Sigismundo, pushed an envelope stuffed full of flies into the grubby hand of the waiting serjeant-at-arms. A ludicrous ballet of bows and scrapes took place, Sigismundo taking photographs the while. After what seemed like hours, Winckelmann was ushered into an inner chamber. His attendant was not allowed to accompany him. Without his trusted lackey at his side, Winckelmann was a little nervous, but his discomfiture did not last long. No more than fifteen seconds passed before he was greeted by his hosts - a swarm of gigantic gnats, whose thrashing wings knocked Winckelmann mercifully unconscious before they devoured him, every last bit of him, grinding him to dust between their powerful biting jaws. It was over in a flash. Then, buzzing and twanging, the swarm left the chamber as it had entered, through a chute, through a chute, through a chute.

A recent survey of British tastes in art announced that “the nation's favourite painting” was a work called, I think, The Singing Butler by Jack Vettriano. Mr Vettriano is a self-taught painter whose often whimsical realism is, of course, execrated by conceptualist noodleheads and the Saatchi-financed “Britart” mafia.

I wondered if a similar survey were to be conducted in Hooting Yard what the result might be, so I contacted the polling agency run by a sister of suburban shaman Joost Van Dongelbraacke and asked them to find out. The methodology they used was perplexing, so much so that it gives me a splitting headache just thinking about it. In fact I think I am going to go and lie down in a darkened room, with a dampened medicinal bandage wrapped around my forehead. [Pause.] That's better. I am pleased to inform you that this morning's post included the agency's definitive result of the poll, scribbled on a piece of blotting paper by Clytemnestra Van Dongelbraacke herself.

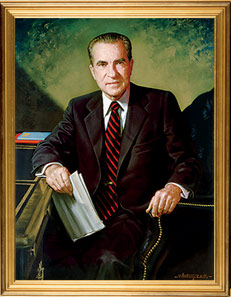

In third place is Allegory of St Bonaventure & The Poolside Attendants, by Sir Gordon Sumner, RA (no relation to that “Stig” person, thankfully). In second place is Some Wheat And A Couple Of Hens by Hattie Le Mesurier. But a clear winner as the favourite painting of all time here at Hooting Yard is the second official portrait of ex-President Richard Milhous Nixon, reproduced below. I think all our readers will appreciate the justice of this choice.

In an addendum to the result, Ms Van Dongelbraacke noted that several thousand proxy votes, by which Mrs Gubbins had sought to influence the outcome in her charmingly malign way, had been discounted. And not only discounted, but incinerated in a big cast iron pot.

and

and

Corky Birdbag, the fiend who pushed a knock-kneed unfortunate into a lake, and stole his bus ticket.

Corky Birdbag, the fiend who pushed a knock-kneed unfortunate into a lake, and stole his bus ticket.

Old Ma Birdbag, whose tunnels were so expertly dug that the police thought moles were responsible.

Old Ma Birdbag, whose tunnels were so expertly dug that the police thought moles were responsible.

Loopy Birdbag, the woman who sent consignments of boiled sweets to Stalin and Barbara Stanwyck at whim.

Loopy Birdbag, the woman who sent consignments of boiled sweets to Stalin and Barbara Stanwyck at whim.

Park Fang Birdbag, desperate banjo player who often stood next to nondescript ponds for no purpose but evil.

Park Fang Birdbag, desperate banjo player who often stood next to nondescript ponds for no purpose but evil.