Some readers will be familiar with the career of the Sino-Dutch artist Ah-Fang Van Der Houygendorp, the man who invented potato-peel engravure. Few people know, however, that he was a keen mountaineer. Keen and inept, that is. Ah-Fang was, if nothing else, a visionary, and he had visions of a haunted mountain, its peak shrouded in inexplicable purple mists like something out of a novel by M P Shiel. Whenever he sat shivering in his tent at base camp, Ah-Fang wondered if this mountain, the one he was about to climb, was the haunted mountain of his mind's eye. He would poke his head out of the frayed flap of his tent, peer up at the majestic rock formation disappearing into the clouds above, and wonder if this, at last, would be the one he had dreamed of since childhood, where he would come face to face with the uncanny, the ineffable.

Physically, Ah-Fang was not really cut out for mountaineering. He was described by a contemporary as “a figure of untold puniness”, and he was indeed tiny and weak, short-sighted, lanky and prone to swooning fits. He was terrified of gnats, horseflies and fruitbats. He had an oversensitive digestive system and had to subsist mostly on thin soup or broth. It was difficult to find a mountaineering team willing to recruit so wretched a specimen, so Ah-Fang did most of his clambering up sheer rock faces solo, a man alone testing himself against the elements.

What he lacked in physical prowess, Ah-Fang made up for with a genius for publicity. Each time he descended from some pitiless escarpment, battered, bruised, hallucinating and in the last stages of exhaustion, the puny alpinist would hold a press conference. At one of these, in 1929, he was questioned closely by Dobson. No one is quite sure what in heaven's name Dobson was doing hanging about in the foothills of the Giant Terrifying Mountains of Tantarabim at the time. We know from the journals of Marigold Chew that Dobson was at work on a series of pamphlets about glue, breadcrumbs and the composer William Hurlstone (1876-1906), whose Bassoon Sonata made him weep, and that he collected the tears in what he called his “Hurlstone bucket”. It is beyond doubt, however, that Dobson bustled through the entrance flap of Ah-Fang Van Der Houygendorp's tent within minutes of the mountaineer's return from the jagged heights of Giant Terrifying Mountain Number Eight, the most challenging of the peaks in the Tantarabim range. The transcript of their conversation has been preserved.

Ah-Fang : Welcome to my press conference.

Dobson : With all due respect, you look very puny for a mountaineer.

Ah-Fang : I have seen things, up in yon mists and clouds, that no human being has ever seen. I want you to tell the world.

Dobson : The lenses of your spectacles are extremely thick, and what I know of the ocular sciences would suggest to me that you are myopic. Added to which, they are steamed up. Your claim to have seen anything at all, let alone something of great import, is, frankly, somewhat dubious.

Ah-Fang : Frankly dubious it may well be, O person with notebook and pencil, but I know whereof I speak, for I was upon that mighty peak engulfed in mists, and you were not.

Dobson : That's true enough. An hour ago I was sitting in one of the huts in these foothills eating porridge. I fled the hut when I saw three bears approaching. I did not know bears roamed these foothills. Were there more bears up on the mountain?

Ah-Fang : Yes, there were bears up there, and there were other things beginning with B.

Dobson : What were those things beginning with B?

Ah-Fang : I could prattle a list of nouns beginning with B, pamphlet person, and you would scuttle away happy, but of greater import is the sort of general mental impression I gained within the mist, an impression which impinged upon my brain in a manner that can only be described as uncanny and redoubtable. For I have witnessed that which I knew from infancy awaited me. Even as a tiny tot I was aware that in some broiling high altitude mist I would come upon the elixir of glory.

Dobson : Let me stop you there, puny mountaineer. I need to sharpen my pencil. Do you have a pencil sharpener?

Ah-Fang : Let me look in my voluminous kitbag.

Dobson : Thank you. While you rummage, I am going to hike up the mountain myself, to add credence to your witterings.

The transcript ends there. For the rest of his life, Dobson never spoke of what he found at the top of that mystic and magical mountain. If asked, he would stare balefully into the distance, as if entranced. But he did write an account of what he found when he returned to Ah-Fang's base camp. It appears as a lengthy footnote in his out-of-print pamphlet He Who Plucks The Strings Of A Banjo In Wintry, Wintry Weather.

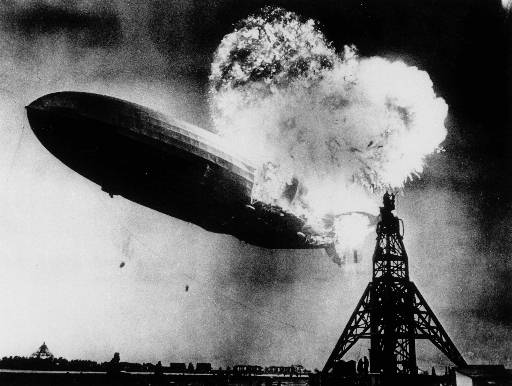

“When I descended from Giant Terrifying Mountain Number Eight,” he wrote, “I expected to find puny alpinist Ah-Fang Van Der Houygendorp awaiting me with a pencil sharpener in his frostbitten hand. I even thought he may have sharpened my pencil for me in my absence, as an act of beneficence. I was in a reflective mood, whistling William Hurlstone's Snow White's Death-Sleep, from The Magic Mirror, as I trudged towards the tent. There were grim, huge-winged birds circling overhead, and I gripped harder the piece of putty in my pocket. Bustling through the flap, as I always bustle through tent-flaps, I found no trace of Ah-Fang, nor of my pencil. The man had vanished with his kitbag, his pencil sharpener, and, I adduced, he had acted like a common thief by taking my pencil with him. I had lost track of time up on the mountain, so I could not guess how long he had been gone. I wondered if, puny as he was, he had been waylaid by the bears who roam those ill-starred foothills, and I half expected to find a pile of chewed bones as I made my sad way to the railway station along the luminous painted footpaths. But I saw no bones, no bears, nothing at all beginning with B, in all the hours it took me to plod away from that weird, unwelcoming place. I never saw Ah-Fang Van Der Houygendorp again, but a year later I learned that he was a passenger aboard the airship the LZ 129 Hindenburg, which exploded in flames while approaching a mooring mast at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in the state of New Jersey in the United States of America. I often find myself wondering if the stub of my pencil was aboard that doomed airship.”