Escape From A Ship On Fireis a Chewist text, in which every other sentence is taken from an anonymous piece of the same title published in the Missionary Annual of 1833. Chewism is named after Dobson's amanuensis Marigold Chew, who pioneered the technique of “stitching” a new text within an existing one in this manner. Note the startlingly modern approach of our 19th century author, who ignores the outbreak of fire and launches straight in to the escape…

There were about four score of us, to use Biblical numbers. Many of the party, having retired to their hammocks soon after the commencement of the storm, were only partially clothed when they made their escape; but the seamen on the watch, in consequence of the heavy rain, having cased themselves in double or treble dresses, supplied their supernumerary articles of clothing to those who had none. I myself gave my hood made out of compressed wheat to a Jesuit priest who had been taking confessions from the stowaways when the tempest struck. We happily succeeded in bringing away two compasses from the binnacle, and a few candles from the cuddy-table, one of them lighted; one bottle of wine, and another of porter, were handed to us, with the tablecloth and a knife, which proved very useful; but the fire raged so fiercely in the body of the vessel, that neither bread nor water could be obtained. We were able to turn the tablecloth into a makeshift tarpaulin, and I chuckled at the appropriateness of its embroidered scene of ducks plashing in a pond.

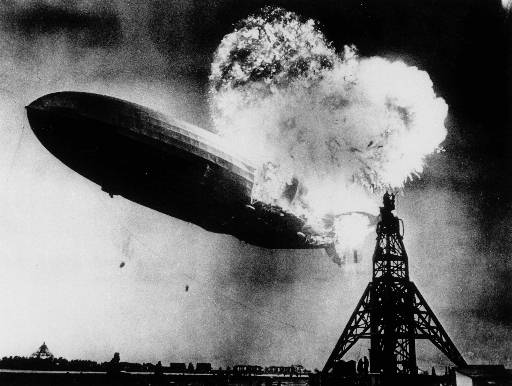

The rain still poured in torrents; the lightning, followed by loud bursting of thunder, continued to stream from one side of the heavens to the other, - one moment dazzling us by its glare, and the next moment leaving us in darkness, relieved only by the red flames of the conflagration from which we were endeavouring to escape. Verily it was like unto the fires of hell, the flaming pit, and it would be no exaggeration to say that the licking flames took on the appearance of fiends armed with pitchforks to poke at the damned.

Our first object was to proceed to a distance from the vessel, lest she should explode and overwhelm us; but, to our inexpressible distress, we discovered that the yawl had no rudder, and that for the two boats we had only three oars. Those were the oars I had varnished back in port. All exertions to obtain more from the ship proved unsuccessful. The acrid stench of burning oars and rudders and tallow and chandlery assailed us. The gig had a rudder; from this they threw out a rope to take us in tow; and, by means of a few paddles, made by tearing up the lining of the boat, we assisted in moving ourselves slowly through the water. I tried to keep up our spirits by singing a shanty, but my voice was cracked and broken and I got no further than the first nine stanzas. Providentially the sea was comparatively smooth, or our overloaded boats would have swamped, and we should only have escaped the flames to have perished in the deep. Throughout my life I had suffered from nightmares wherein I was gobbled up in the jaws of some eldritch aquatic being resembling a giant squid with pulsating suckers, and now I feared that all those tossing and turning nights had been a premonition of my actual doom.

The wind was light, but variable, and, acting on the sails, which, being drenched with the rain, did not soon take fire, drove the burning mass, in terrific grandeur, over the surface of the ocean, the darkness of which was only illuminated by the quick glancing of the lightning or the glare of the conflagration. But what could account for the hissing and seething noises, like a thousand deranged baby pigs, now soft, now deafeningly loud, which seemed to be pursuing us in our hectic progress?

Our situation was for some time extremely perilous. Ach, the damnable sea! The vessel neared us more than once, and apparently threatened to involve us in one common destruction. Great crashing waves tumbled over us and we gibbered in terror; then one old salt developed a massive nosebleed which he tried to staunch with a roll of bandage he had looted from the purser's cabin just before we abandoned ship; he knew he would hang for theft, but a brute sense of survival had him pulling at an oar with one hand and fumbling with the bandage with the other. The cargo, consisting of dry provisions, spirits, cotton goods, and other articles equally combustible, burned with great violence, while the fury of the destroying element, the amazing height of the flames, the continued storm, amidst the thick darkness of the night, rendered the scene appalling and terrible.

I noticed that even in the midst of the mayhem, our ship's artist, Binnie, was scribbling frantically in his tattered and seawater-soaked sketchpad, drawings which would one day go on show at some godforsaken seaside museum, unvisited and unsung. About ten o'clock, the masts, after swaying from side to side, fell with a dreadful crash into the sea, and the hull of the vessel continued to burn amidst the shattered fragments of the wreck, till the sides were consumed to the water's edge. At five past ten, an angel appeared momentarily in the black forbidding sky, or it may have been a guillemot. The spectacle was truly magnificent, could it even have been contemplated by us without a recollection of our own circumstances. Those circumstances were perilous indeed; only once before had I been involved in a burning shipwreck, and that had been child's play in comparison.The torments endured by the dogs, sheep, and other animals on board, at any other time would have excited our deepest commiseration; but at present, the object before us, our stately ship, that had for the last four months been our social home, the scene of our enjoyments, our labours, and our rest, now a prey to the destroying element; the suddenness with which we had been hurried from circumstances of comfort and comparative security, to those of destitution and peril, and with which the most exhilarating hopes had been exchanged for disappointment as unexpected as it was afflictive; the sudden death of the two seamen, our own narrow escape, and lonely situation on the face of the deep, and the great probability even yet, although we had succeeded in removing to a greater distance from the vessel, that we ourselves should never again see the light of day, or set foot on solid ground, absorbed every feeling. Every feeling, that is, except one; and it may be that I speak only for myself, but among the jumble of terror and loss and despair and woe I yet had a vision of the pantry in my parents' pie shop, its shelves stacked with jar upon jar of pickled and jellied blubber products which remarkably, even in this ferocious cataclysm, made my mouth water.For some time the silence was scarcely broken, and the thoughts of many, I doubt not, were engaged on subjects most suitable to immortal beings on the brink of eternity. I myself took comfort in my pie shop pantry thoughts.

The number of persons in the two boats was forty-eight; and all, with the exception of the two ladies, who bore this severe visitation with uncommon fortitude, worked by turns at the oars and paddles. Good Victorians that they were, despite it being the year 1963, the ladies darned socks and cooed gentle hymns as the storm blustered around us. After some time, to our great relief, the rain ceased; the labour of baling water from the boats was then considerably diminished. Our feet, nevertheless, were drenched, except for those of the wily sailor who had smeared the lower half of his body with boar's grease. We were frequently hailed during the night by our companions in the small boat, and returned the call, while the brave and generous-hearted seamen occasionally enlivened the solitude of the deep by a simultaneous “Hurra!” to cheer each others' labours, and to animate their spirits. Throwing pingpong balls across the storm-tossed seas from one boat to the other was another way of coping with our predicament.

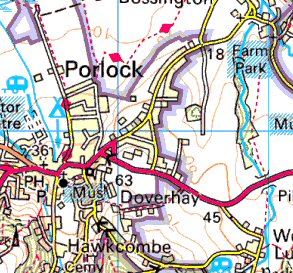

The Tanjore rose in the water as its contents were gradually consumed. The flames roared pitilessly. We saw it burning the whole night, and at day-break could distinguish a column of smoke, which, however, soon ceased, and every sign of our favourite vessel disappeared. Dawn was approaching. When the sun rose, our anxiety and uncertainty as to our situation were greatly relieved by discovering land ahead; the sight of it filled us with grateful joy, and nerved us with fresh vigour for the exertion required in managing the boats. I wondered if by some freak of chance we had lit upon the Island of Abundant Spinach, of which I had so often read. With the advance of the day we discerned more clearly the nature of the country.

Alas! It was wild and covered with jungle, without any appearance of population: could we have got ashore, therefore, many of us might have perished before assistance could have been procured; but the breakers, dashing upon the rocks, convinced us that landing was impracticable. Stuck in our boats, we tried to chat about mundane things; railway timetables, soup recipes, the film career of Rex Harrison. In the course of the morning we discovered a native vessel, or dhoney, lying at anchor, at some distance: the wind at that time beginning to favour us, every means was devised to render it available. By now most of us were too exhausted to row, even the sailor with the nosebleed, who had collapsed and was lying in the bottom of the boat for all the world like a felled marble statue of a magnificent god. In the yawl we extended the tablecloth as a sail, and in the other boat a blanket served the same purpose. I have not mentioned the blanket before, for reasons which even the most astute reader can only guess at; let us just say that this blanket's warp and weft were not of this earth, nor of any imaginable planet. This additional help was the more seasonable, as the rays of the sun had become almost intolerable to our partially covered bodies. Despite there being a gang of violent pagan sun-worshippers aboard, we cursed that bright and battering orb. Some of the seamen attempted to quench their thirst by salt water: but the passengers encouraged each other to abstain. It is astonishing how determined one can be if faced with a crack on the skull from a gas canister.

About noon we reached the dhoney. Every last one of us had survived that terrible night. The natives on board were astonished and alarmed at our appearance, and expressed some unwillingness to receive us; but our circumstances would admit of no denial; and we scarcely waited till our Singalese fellow-passenger could interpret to them our situation and our wants, before we ascended the sides of their vessel, assuring them that every expense and loss sustained on our account should be amply repaid. The very next day, I set sail once more, alone, bound for Greenland, little knowing that I would twice more be imperilled on the vast and thundering ocean, dashed against rocks and almost drowned in bilgewater, before I would once again step over the threshhold of the pie shop, the prodigal daughter returning to her shrivelled and infected parents, home, home from the sea.