The title of this piece ought to be For Those In Peril On The Sea, but so caught up am I in my series of “On…” essay titles that it seemed a shame to muck it up. Hence the somewhat forced rephrasing, which doesn’t even pass muster as an entry in an index, where it would be better put as Sea, The, For Those In Peril On. I am sure there are other ways to rearrange the words, depending upon which term one wished to give due prominence – Those or Peril, for example – but I am not going to waste my time and yours by further shilly-shallying. We need to get down to business, which today is to respond to the following letter, received from reader Tim Thurn:

Now look here, Mr Key, he hectors, I cannot be alone in wondering why you seem never to mention the sinking of the RMS Titanic. You bang on and on, to the point of tedium, about the Munich Air Disaster and the Hindenburg and, though they are not disasters of the same kidney, notable twentieth century events such as the Kennedy assassination and the Tet Offensive. Yet of the Titanic, barely a word, though a brief search reveals that you use (or overuse) the word titanic to describe the pamphleteer Dobson. This weekend we will mark the one hundredth anniversary of the loss of the liner in the icy wastes of the north Atlantic, so I think it is about bloody time you turned your attention to it, if you can drag yourself away from peering myopically out of the window at crows and at whatever else you peer at when you look out of the window. Get a grip. Passionately yours, Tim Thurn.

Well, that’s me told. It might surprise Mr Thurn to learn that I am something of a Titanic scholar, having at one point in my life read many, many books on the subject. I think I may acquit myself fairly well were I to take it as a quiz subject. To take a snippet at random, I know, for example, that second mate Charles Lightoller, who survived the sinking, was later decorated for various heroics during the First World War and played his part in the Second by sailing one of the “little ships” across the channel in the evacuation of Dunkirk. Also, if he had been reading these essays, Mr Thurn would know that I grew up living not far away from Eva Hart, one of the longest-lived survivors of the disaster, though it is true that I never went calling on her to winkle out her memories, nor did I ever go the pub named after her to raise a glass in memory of all those who drowned on that dreadful night in what Mr Thurn likes to call “the icy wastes of the north Atlantic”.

Of all the books I read, my favourite was Titanic : Psychic Forewarnings Of A Tragedy by George Behe (1989), which collects over one hundred accounts of premonitory dreams and visions and so on. Amusingly, as far as I recall, every single one of these accounts was recorded after the fifteenth of April 1912, so we have someone writing in, say, 1920 about a dream they had in 1910. Interestingly, not one of the psychic forewarnings features either Kate Winslet or Leonardo Di Caprio, who many young persons today believe portrayed real historical characters in the 1997 James Cameron blockbuster. Given the parlous state of history teaching in our self-esteem and diversity hubs, it is a small mercy that I have yet to hear of a youngster exclaiming with shock that the ship sinks at the end of the film.

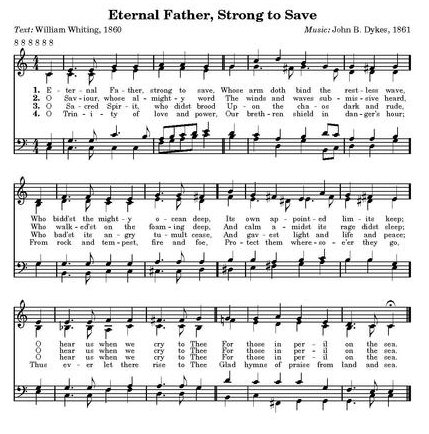

On Sunday, I shall be marking the anniversary as I always do. I corral a choir of tinies and take them to Nameless Pond, my local duckpond. It is not the north Atlantic, nor at this time of year is it icy, nor is it indeed the sea, but I live far from the sea, and it is, after all, a body of water, and a better site for the commemoration than, say, a bathtub or butler sink. We launch a paper boat upon the pond, and then the tinies sing the Victorian hymn Eternal Father, Strong To Save by William Whiting, which, of course, contains the couplet “Oh, hear us when we cry to Thee, / For those in peril on the sea!” The hymn was also used by Benjamin Britten in Noye’s Fludde (1957), though not sung by the tinies. It was also the final hymn sung at the Sunday service on the Titanic on Sunday the fourteenth of April 1912, just hours before the sinking. If our paper boat has been folded into shape with sufficient cack-handedness, it usually sinks under the weight of its cargo of pebbles while the tinies are singing. If it does not, I get them to repeat the hymn from the beginning, while chucking further pebbles at the paper boat in hopes of scuppering it. We like to pretend that the various ducks disporting themselves upon the pond are the Titanic’s lifeboats. In order to compensate for the disparities in scale – some of the ducks are actually bigger than our paper boat – we squint or, in my case, remove our spectacles so the whole scene is a blur.

One year, during this mournful little ceremony, a passing duckpond-circumnavigating pedestrian buttonholed me to ask what we were doing. When I explained, he pointed out that, though we had recreated the ship (a paper boat) and the lifeboats (the ducks), there was nothing to represent the iceberg. Without this, he said, our memorial singsong was a mere farrago. Sadly, I had to agree. It is thus pleasing to note that, as the tone of Nameless Pond and its surroundings are dragged ever further into barbarism by the local riffraff, some antisocial scalliwag has tossed an abandoned fridge into the water.

Perhaps Mr Thurn should come and join us on Sunday, and bring his funerary violin.

One can’t help feeling that the ‘antisocial scalliwag’ has been rather short-changed in this account. When he or she ‘tossed an abandoned fridge into the water’ he or she was, whether wittingly or no, redeeming it from abandonment into gainful (albeit emblematic) employment in Mr Key’s charming and apposite homage to the marine upset in question.

If, on the other hand, the fridge was not abandoned *until* the scalliwag tossed it into the pond, then he or she was indeed being antisocial.

Either way, it’s quite a feat to ‘toss’ a fridge into a pond. Perhaps ‘antisocial scalliwag’ could be rendered as ‘unusually muscular and conceivably antisocial scalliwag’. Or would that sound a bit too forced and clotted?

Of all the larger white goods one might find in the average kitchen I’d suggest the fridge is one of the easier to toss into a pond.

The weight rankings might look something like this:

Featherweight: Micro-wave Oven

Lightweight: Fridge

Middleweight: Cooker

Heavyweight: Washing Machine

Super Heavyweight: AGA

OSM