A recently dug-up diary for this day in 1900:

I am a pimply ragamuffin of no great consequence in this world. But my doings will resound down the ages, and be pored over by generations yet unborn, because I am keeping this diary and, at intervals, every one hundred pages or so, I put the scribbled sheets into a bag and the bag into a sack and the sack into a box and the box I bury in a field, in different fields dotted hither and thither, where one day in the future a man wielding a spade or shovel will dig up my diary and it will be pored over, as I said just now, by generations yet unborn.

First thing this morning, I gazed into the greasy glass and counted my pimples. There is a different number every day, which I jot down in a separate notebook. It seems that overnight, while I lie on my straw pallet in the corner of the barn, thrashing about, fast asleep yet disturbed by terrible dreams, several pimples erupt and several others subside or vanish. Sometimes I trace the patterns they form on my whey-coloured face, just in case, like the constellations of stars in the sky, there is a message to be read in them. I have buried some of my pimple diagrams alongside my diary pages, so perhaps in the future a significance I cannot fathom will be apparent to those who come after me, armed as they may be with a greater knowledge of patterns and mysteries and pimple distribution.

Then I took my begging bowl and sat on a clump by a verge and hoped for alms. A passing person gave me an old holed woollen sock to serve as a mitten for my tiny frozen hand. Oddly, both of my hands are unpimpled. Another passing person had no matching sock, alas, but did give me a bar of soap. But today I had chosen the wrong clump, or the wrong verge, or both, because nobody else passed all day long.

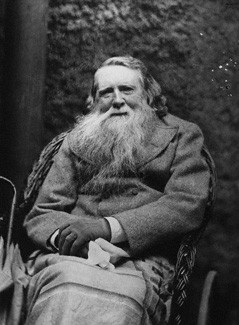

Towards sunset I trudged off to Brantwood to see my one pal, the mad old gent with the Old Testament beard whose demented ravings I keep meaning to transcribe. But I will need a different notebook, different from my diary notebooks and my pimple count notebook. Perhaps I will be able to get one in exchange for the bar of soap from a filthy stationer.

As I approached Brantwood, skirting the reservoir and passing the waterfall and the harbour, where the Jumping Jenny was tied to a painter, and the ice house and the slate seat facing the tumbling stream, I sensed something amiss. My pimples grew hot, a sure sign of impending calamity. And indeed, as I came to the house, out of it emerged a black-clad fellow with a grave look etched upon his countenance, who exclaimed:

“Mistah Ruskin – he dead.”