You don’t expect to find a cad in a grotto. But that is exactly what I discovered during a spot of seaside spelunking many years ago. I had abseiled down a cliff, having been told by my colleague Dennis Pivot that there was, at its foot, partly submerged under water, a grotto which, he thought, was the portal to a magnificent and extensive system of caves never before explored.

“What makes you think that, Dennis?” I had asked him, as we ate sausages in a seaside cafeteria.

“Clues strewn in various rare manuscripts of olden times,” he said. When I pressed him for further details, he pretended to be chewing on a piece of gristle, then gagged, spat into a napkin, and keeled over. It was a convincing performance, and at the time I had absolutely no idea he was dissembling.

I hired some kit and headed for the cliff. It was a squally day. Gulls were screaming their heads off. My ears are oversensitive to certain bird shrieks, so I stuffed them with cotton wool. Then I abseiled like the abseiling expert I am down the cliff face. What with the cotton wool and my cushioned helmet I couldn’t hear a thing. At the bottom of the cliff, I swung myself into the grotto. I unfastened myself from my abseiling rope and stood for a moment or two, knee deep in sloshing seawater, to catch my breath. That is when I saw the cad.

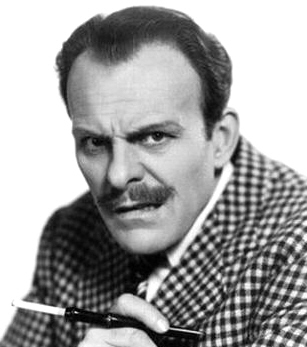

He came looming out of the Platonic shadows at the back of the grotto, a dapper fellow in spite of the cheapness of his suit. Like many a postwar cad, he bore a striking resemblance to the actor Terry-Thomas (1911-1990).

“Hello old chap!” he said, “I say, you couldn’t see your way to loaning me a few bob, could you? Had a run of bad luck on the old gee-gees, you know how it is.”

I couldn’t hear a word he said, and gestured to indicate as much. Then I took off my helmet and prised the cotton wool out of my ears and asked him to repeat himself. After he had done so, I explained that I never carried cash when abseiling, for fear it might fall from my pocket into the merciless sea.

“Drat!”, he said, and then offered to place some bets for me if I met up with him at Waterloo Station on the following Thursday and forwarded him several hundred pounds.

I promised to think about it, though in truth my puritanical ways made it very unlikely that I would ever get embroiled in any form of gambling.

“Tell me something,” I said, “You seem to be familiar with this grotto. I’ve been led to believe it leads to a magnificent and extensive system of caves never before explored. Is that indeed the case?”

“I haven’t got the foggiest,” he said, “Only been here a couple of weeks, haven’t quite got my bearings.”

This surprised me. I had always thought it a characteristic of cads that they were quick to grasp the possibilities of whatever circumstances they found themselves in. I put this to him, without actually calling him a cad. By way of reply, he changed the subject.

“I say, you couldn’t loan me those bits of cotton wool, could you? I’m being driven crackers by the shrieking of those damnable gulls.”

I was reluctant to relinquish my makeshift earmuffs, and told him so. I still cannot remember how he managed to wheedle them out of me, nor how he convinced me to let him try on my abseiling harness, which, having donned, he attached to the rope dangling at the grotto’s opening, whereupon he rapidly ascended, leaving me alone. The sloshing seawater was now up to my waist.

There was nothing for it but to make my way deeper into the grotto, in the hope of discovering a magnificent and extensive system of caves never before explored. But was my colleague Dennis Pivot right, or was he talking twaddle, as he so often did?

On this occasion, I am relieved to report, he was bang on the money. I spent several days clambering about underground, the first man to see, oh!, such wonders!

But when Thursday came I determined to find my way back to the grotto and then, somehow, up the cliff face. I remembered I had an appointment to meet the cad at Waterloo Station, and though I had no intention of giving him several hundred pounds to bet on the horses on my behalf, I dearly wanted to retrieve my abseiling harness and rope and cotton wool.

When I got to the grotto, the tide was in, and the sloshing seawater came up to my neck. Without my abseiling gear, I knew I could not hope to scale the cliff, so I decided to plunge ahead and make a swim for it. There was a terrible risk that I would be dashed to pieces on the rocks. Luckily, I managed, by dint of advanced swimming techniques, to steer my way through the tremendous currents, and by midday I was panting on a shingle beach. I was exhausted and sodden and had numerous tiny crustacean beings snagged in my hair, but I was alive.

Stopping only for a reviving cuppa in a seaside cafeteria, I caught a train to Waterloo Station. And there, on the concourse, waiting for me, I spotted the cad. I squelched towards him.

“There you are, old bean,” he said, “Have you got a wodge of the folding stuff?”

“No I have not!” I cried, “I am of puritanical bent and I never bet on the horses. I have come for my abseiling harness and rope and my cotton wool, with which I entrusted you in the grotto.”

“Of course, old boy, of course,” he said, a gleam of mischief in his eyes, “I put them in a locker for safe keeping. Here – “ and he handed me a key – “Number 666. Be seeing you!” And he scarpered.

I asked a railway person where the lockers were, and went straight to them. I inserted the key into the lock of locker number 666, and opened it. There was no sign of my harness, my rope, and my cotton wool. Instead, what I found in the locker was the thing that, had I but known, I would have dropped as surely as one drops a burning potato, for it led to my utter ruin in this world, and my damnation in the world to come.

Terry-Thomas, for younger readers who may not know what a postwar cad looked like

Good tract!