There is an old joke, a proper chestnut, which begins “A mod and a rocker and a widow and an orphan walk into a bar…” The Oxford English Dictionary does not tell us why we use the word chestnut in this context. It says that the usage “probably” originated in the United States and, curiously, that “the newspapers of 1886–7 contain numerous circumstantial explanations palpably invented for the purpose”. What was in the air in those two years that suddenly made this a debatable issue? Perhaps there was a spate of chestnut madness, similar to the carrot madness that ran rife in Belgium and northern France in the 1850s. No convincing explanation has ever been given for the latter episode, and it happened too late to be addressed by Charles Mackay in Extraordinary Popular Delusions And The Madness Of Crowds (1841).

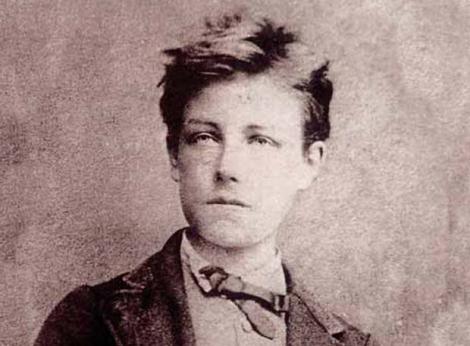

The bar into which the mod and the rocker and the widow and the orphan walk in the joke is usually specified to be a seafront bar, no doubt on account of the infamous seaside resort pitched battles between mods and rockers – though not between widows and orphans – in the mid-1960s. Interestingly, however, in one persistently popular variant of the gag, the punchline depends heavily on the bar being the drinking den known as the Tip Top Annexe, a rather seedy establishment on the Crescent in Aden, when it was Prince of Wales Crescent in the British Protectorate of Aden. This was close to the Grand Hotel De L’Univers, where Arthur Rimbaud fetched up on his arrival in Aden in August 1880. There is an echo of Rimbaud in some versions of the joke, when the rocker, or sometimes the widow, is said to have “dried [him- or herself] in the air of crime”. The joke works well enough with or without this observation, as indeed it does when it is not set in the Tip Top Annexe, so long as the punchline is modified accordingly.

In his study Draining The Last Vestiges Of Humour Out Of The Funniest Gags, the pop psychologist Dr Desmond Drain frets away, like a dog with a bone, at the idea that the mod and the rocker and the widow and the orphan are not, as we would assume, four persons, but two. In this reading, the mod is the widow and the rocker is the orphan. He goes on to posit, in further garbled analytical posturing, that they are a couple in love, smitten with each other, who, before entering the bar – which may or may not be the Tip Top Annexe – have had a tiff, because of a crime committed, either by the mod/widow or the rocker/orphan, where one sides with, or personifies, law and order, and the other represents the forces of crime, disorder, and even, at a pinch, existential chaos. Dr Drain’s own preconceptions and prejudices regarding the values inherent in the different types of music championed by mods and rockers tend to colour his argument, as does the fact that he was orphaned at an early age, when his parents died in the riots which occurred during the outbreak of citrus fruit madness in south coast seaside resorts in the 1970s. Whether or not one gives credence to his interpretation, most people agree that the joke works better with four protagonists rather than two.

Or rather, with five protagonists, for let us not forget that essential addendum, the barman who serves their drinks. Tip Top Annexe types like to have him wearing either a fez or a pith helmet, but any sort of headgear serves equally well. He does have to wear something on his head, however, simply to be able to incorporate into the joke the part where he takes it off and places it on the bar counter. As an experiment, I once told the joke without including this detail and, as expected, it fell completely flat. In fact, some among my audience were so miffed, in spite of being fully aware they had been assembled for the specific purpose of experimental joke-telling research, that they stooped to pick up pebbles and shingle from the beach and pelted me with them, until I had to make a run for it to the safety of the railway station. At least it was pebbles rather than shivs, otherwise it would have been like a scene from Brighton Rock. It was probably not a good idea to conduct my research at the seaside.

In some variants of the joke, though intriguingly not always those which insist upon the Tip Top Annexe setting in Aden, the barman’s appearance is given, and he closely resembles Arthur Rimbaud. We are told he has “the perfectly oval face of an angel in exile” (Verlaine), and is “sympathique… speaks little, and accompanies his brief comments with odd little cutting gestures with his right hand” (Bardey). It is with one of these cutting gestures that the barman accidentally knocks over the absinthe ordered by the mod – or sometimes by the rocker – leading directly to what today’s barbarians might call the “LOL moment, innit” midway through the joke, a particularly clever insertion as it is often taken as the punchline. That the joke then continues only serves to heighten the uproarious hilarity of its side-splitting conclusion. Where the odd little cutting gestures by the barman are absent, the glass of absinthe, or lemonade or vapido ague, is knocked over by another agency, which might be a gust of wind, a stray dog, or an invisible sprite.

It is the venerability of the joke, its status as an old chestnut – not a carrot nor a piece of citrus fruit – which has led, in years of telling and retelling, to so many variations. Their profusion has persuaded some that an effort ought to be made to recover the Ur-joke, stripped of all inessentials. One such attempt, attributed to the japester Fat Billy Cannonball, which has gone down a storm at certain northern seaside resorts, dispenses with the mod and the rocker and the widow and the orphan, and has Arthur Rimbaud himself, walking into the bar of the Grand Hotel De L’Univers on Prince of Wales Crescent in the British Protectorate of Aden on a specific day in August 1880, and ordering an absinthe, or “this sage-bush of the glaciers”, as he puts it. I have yet to hear this version in its entirety, but I have already been rendered helpless with mirth, and must roll about on the floor, convulsed, as if in the throes of a fit. Excuse me while I do just that.