I went for a morning trudge around Nameless Pond and, having completed a circumnavigation, I sat on a bench for a breather. I lit a cigarette and contemplated the ducks. Foolishly, I had left my iDuck at home, so I had no idea whether I was contemplating teal or mergansers, or indeed quite other types of duck. After some minutes, I was joined on the bench by an ancient and withered gent whose approach I had not been aware of. He had an air of the shabby genteel about him, and milky eyes.

“Good morning,” he said, without looking at me.

“Hello,” I replied, hoping that would be the extent of our conversation. But no.

“I see you are contemplating the ducks on the pond,” he went on, “An activity to which I myself have devoted many hours over the years. Many, many hours over many, many years, for as you can see I am ancient and withered. I am almost as old as Methuselah. That is not a name you come across very often nowadays, is it?” He did not pause to allow a response. “In fact I cannot think of a single Methuselah I have ever met, and I have met an enormous number of people. I used to be quite a gadabout before the stiffness and withering slowed me down. I gadded hither and thither and met people from all walks of life, but never a Methuselah. Unless of course that is your name?”

“I’m afraid not,” I said, “I am Mr Key.”

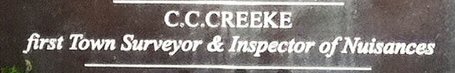

“I am very pleased to meet you, Mr Key. I am Mr Creeke, C. C. Creeke. The funny thing is, my parents never divulged what the Cs stand for, and my birth certificate was rendered illegible in one of those overturned bleach bottle mishaps one occasionally reads about in the popular press. My father was a musician and my mother was a Marxist-Leninist, so I have long suspected that I was named after Cornelius Cardew, the composer of 10,000 Nails In The Coffin Of Imperialism, among other works, or possibly after Chris Cutler, the drummer and percussionist in Henry Cow and roughly six hundred and forty-five other bands and combos and one-off projects. Given my ancientness either may be chronologically dubious, as parental choices, but the world is a very mysterious place, Mr Key, as I am sure you have noticed.”

Again he continued to babble on without awaiting any kind of reply.

“In a world of such mystery and bafflement it is well to have at least one fixed point of clarity and order. I found it at Pang Hill Orphanage, where for many years I was retained as the Inspector of Nuisances. I see you are raising your eyebrows.”

I was not, and in any case he was still not looking at me.

“It surprises you to learn that any of the orphans at Pang Hill could ever have been deemed nuisances. When would they ever have had the time to be mischievous and pesky and scampish?, you wonder. Confined at night to their iron cots, and in the daytime huddled in the cellar labouring away by the dim light of a single Toc H lamp, betweentimes scoffing their gruel and having compulsory singsongs and prostrating themselves before strange voodoo idols and all the other activities of the orphanage day, they would surely have been too exhausted to be nuisances. So you think. But believe me, Mr Key, when I made my weekly visits, clanging my bell, there would be a parade of nuisances whom it was my duty to inspect. And inspect them I did, with magnifying lenses and calipers and measuring tape, and then I wrote my report for the beadle. What became of my reports I never knew, and never asked. I had other things on my plate.

“For Pang Hill Orphanage and its nuisances demanded my attention on only one day of the week. The rest of the time I was engaged on the first ever survey of Pointy Town. I surveyed as many of the pointy bits as a man could reasonably be expected to survey in one working lifetime. But whereas Pang Hill was a fixed point of clarity and order, Pointy Town was quite the opposite. Indeed, surveying all those pointy bits drove me crackers. There was no end to them, nor any sense to them, and it wore me down, slowly but surely. That is why I am now so withered. Oh, look! A pochard!”

And indeed, a pochard had come dabbling close to the bank of the pond, so close I could have leaned forward and grabbed it and wrung its neck, had I been so minded. But I have put my duck-strangling days behind me. It was always a foolish and unpleasant hobby.

While my attention was on the pochard, C. C. Creeke vanished. I cannot put it more plainly than that. Just as he had appeared on the bench without my noticing his advent, so he left it. I looked around, wildly, but there was no trace of him. I was baffled, but the world is indeed a very mysterious place.

It was time to go home. I got up and trudged on my way, and then I spotted, half hidden in the sordid undergrowth beside the pond, a plinth. Brushing the nettles aside, I read:

The foliage was too thickly entangled for me to discover what was atop the plinth. And when I returned, the next day, armed with a pair of secateurs, I was unable to find it again. I searched and searched, but eventually I gave up, and sat on the bench, and smoked, and contemplated the ducks.

[Thanks to Outa_Spaceman for the snap,]