I was discussing the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen with the ghost of his first wife, Doris.

“Is it true” I asked, “That Stockhausen was covertly funded by the CIA in an attempt to demoralise German culture after the Second World War?”

Doris was one of those mute ghosts we’ve been hearing so much about lately but I hoped she would either nod or shake her head in reply. But her phantom head remained motionless atop her phantom neck, jutting at a disconcerting angle from between her phantom shoulders, draped in a shawl of surpassing loveliness which was all too real, as I knew because I had touched it, when gently pressing her down into her chair.

Well, not her chair, but a chair, the chair into which I press all my ghostly visitors. Unless you get them firmly nestled, they have a tendency to float and flit about the room, and even to splay themselves across the ceiling. Not all ghosts come when I summon them, but Doris did. A few seconds after my ear-splitting incantation, there was a faint tapping at my door. I opened it, and there, already, was the ghost of Doris Stockhausen. She handed over my fifty-pfennig fee, in cash that was pleasingly of this too too solid world – I checked – and allowed herself to be ushered in, and settled in the chair.

But I had not reckoned on her being a mute ghost. She sat across from me, fixing me with her baleful countenance, silent as the grave from which I had summoned her. With no prospect of the conversation I had so looked forward to, I went to rummage among my cassettes until I found the tape of her ex-husband’s Stimmung. I wondered if, hearing it again after all these years, Doris might be in some measure animated.

When I returned to the room, Doris had escaped her chair and was splayed across the ceiling. The surpassingly lovely shawl was hanging from her phantom shoulders, so I gave it a tug, hoping to dislodge her. And indeed, she lost contact with the ceiling, hovering in mid-air for a moment before darting this way and that, finally settling atop a toffee cable. Oops, I mean a coffee table. Using thumb-tacks, I secured the shawl to the table, holding Doris in place. The table was one of those fashionably distressed coffee tables, so the addition of a dozen tack-pricks would only add to its faux dilapidation.

There was every possibility that the ghost of Doris could slip or waft from beneath the shawl and go skittering about. I slotted the cassette into the cassette player, pressed “Play”, and cranked up the volume.

“Let us listen to Stimmung, Frau Stockhausen!” I cried, with perhaps an excess of jollity.

The tape hissed, and then the room was filled with the sound of a German man moaning melodiouslyish. Startled, I saw Doris suddenly clap her ghostly hands over her ghostly ears. Then she began to vibrate, horribly. I turned the music off, but it was too late. With a whoosh!, Doris shot up to the ceiling, taking the surpassingly lovely shawl and the coffee table with her.

Try as I might, I could not coax her down. Not only was I unable to use my coffee table to display my coffee table books, of which I owned oodles, but soon enough Doris outstayed her allotted time in the realm of the living afforded by the fifty-pfennig fee. Six weeks later she was still there, clinging to my ceiling, the shawl and table swinging gently beneath her in time with her ghostly panting. I had not realised how violently ghosts pant, particularly the mute ones.

At my wits’ end, I consulted a local spirit medium who specialised in the demoralisation of German culture in the aftermath of World War Two. He was a rather curious fellow. His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion, and his straight black lips. His voice was booming and monotonous, empty of human expression and lacking any variation in tone or cadence.

“Hand. Me. That. Cassette. Player.” he boomed, standing directly beneath the ghost of Doris and the shawl and the coffee table.

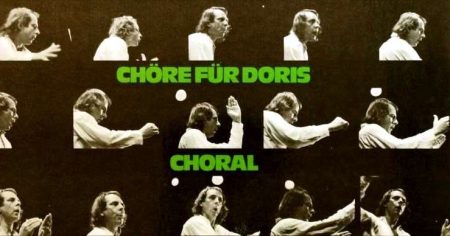

I did his bidding, and he took from his pocket a battered cassette tape. I shall never forget what happened next. He plopped the cassette into the machine, pressed “Play”, and cranked up the volume. There was the familiar hiss, and then the sound of a capella German voices warbling melodiously, with no ish about it, the first of the Choruses For Doris, by Doris’ ex-husband Karlheinz Stockhausen.

The spirit medium stepped – or rather, lumbered grotesquely – to one side, and the ghost of Doris let go of the ceiling and wafted elegantly down, shawl and coffee table and all, the table landing with a slight bump on the floor. As the chorus continued, the medium removed the thumb-tacks one by one. The ghost of Doris rose slghtly, hovering just above the coffee table, shimmered for a few seconds, and then seemed to dissolve before my eyes. Weirdly, that indubitably real unghostly shawl, of surpassing loveliness, dissolved with her. Then, even more weirdly, the spirit medium dissolved too, taking a handful of my thumb-tacks with him into ethereal realms beyond my puny understanding.

I was alone in my room, listening to the Choruses For Doris, and thinking to myself that postwar German culture had not, after all, been demoralised, in spite of the alleged efforts of the CIA.