On a frosty winter’s morning in the middle of the twentieth century, legendary athletics coach Old Halob stood at the side of a running track, stopwatch in hand, Homburg on head, racked with catarrh and puffing a cigarette. He was much perturbed. His protégé, fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol, was pounding round and round the track at ever higher speeds, but Old Halob’s brain was a whirling chaos. He had not slept for weeks, and he was even more bad tempered than usual. The spindly fictional sprinter whizzing past him was causing the one-time secret policeman much vexation. He was running faster than ever, and when pole-vaulting he was pole-vaulting higher than ever. He was winning medals and cups in all sorts of fictional athletics meetings, not least the Gloriously Shining Medallion Of Gack, awarded to the champ of champs in the Pointy Town Auxiliary Substandard Jumping About League Reserve Heats. But for Old Halob, all this was as nought. For what he most desired for Bobnit Tivol was fame, and fame eluded him.

In the narrow, enclosed world of fictional athletics Bobnit Tivol was of course a name to be reckoned with. Yet in the wider world he remained unknown. It had long been the dream of Old Halob that his protégé be the cynosure of all eyes, a titan worshipped not just by fictional athletics fans but by all and sundry, the great and good and the hoi polloi. It may be, as some cynics liked to snigger, that the wily old coach wished to exploit the sprinter for financial gain. Worldwide fame would bring the money pouring in, whether it be for hiring out his image to be emblazoned on cardboard breakfast cereal packets or for personal appearances at the opening of fairgrounds. Nowadays we are used to such commercial shenanigans, but half a century ago they were almost unheard of. Old Halob remains an old fashioned figure in many ways, but he always saw himself as a man o’ the future, and in pursuit of that vision he strained every sinew, sclerotic though his sinews may have been, if there is such a thing as a sclerotic sinew.

So on that frosty, icy morning, Old Halob took one last puff on his acrid Serbian cigarette, and, barking a command to the fictional athlete to keep sprinting faster and faster round the running track until his return, he trudged away. He headed for an insalubrious part of town where he might find solace in rotgut hooch and squalor. And it was as he was about to turn down a particularly dismal alleyway that he was accosted by an urchin hawking grubby wares.

“Oi, mister, I’m your urchin if you need some spent matches or tattered bootlaces or chewed-up dog biscuits or leaking batteries or contaminated sausages or poisoned cans of Squelcho! or regurgitated hairballs or back copies of the Reader’s Digest! Everything’s a half-crown!”

“Your wares are preposterously expensive,” said Old Halob, “But here is a half-crown for a back copy of the Reader’s Digest. I shall want something to read while I benumb my brain with hooch.”

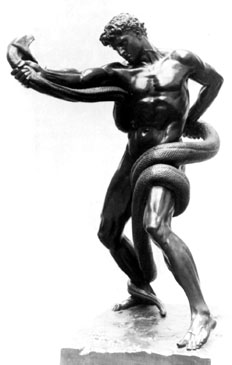

Later, sitting in the dinge of an ill-starred tavern glugging from a bottle of 90% proof Monsignor’s Spasm, Old Halob flicked through the pages of the magazine hoping to find something that might take his mind off his woes. There was an article entitled “I Am John’s Head” which diverted him briefly, as did a piece about a heroic anti-communist housewife. He made a stab at a quiz based on anagrams of “Ayn Rand”. Then he came upon a picture spread of artworks by Sir Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), and saw something that made fireworks go off in his brain. It was a photograph of a sculpture by Leighton entitled Athlete Wrestling With A Python (1877). Old Halob was transfixed. He ordered another bottle of hooch, and began to formulate a scheme.

Leighton’s sculpture had been a great popular success in its day. Why, then, if Old Halob were to create a modern adaptation, Fictional Athlete Wrestling With A Real Python, would that not equally astound the public? What could better propel fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol to universal acclaim than the sight of him doing battle with an all too real python, and winning?

Draining his second bottle and reeling out of the tavern into the ghastly streets, Old Halob decided to leave his spindly protégé haring round the track for the time being while he set off to find a python. There was a zoo and a number of menageries in the town, but they were all shut, it being a Thursday. Tacked up on a lamppost he saw a notice about a newly opened snakepit, and boarded a tram to take him there, but the tram crashed into a parade of horses and Old Halob was among a number of tram passengers and equestriennes who were ferried to a clinic on stretchers. It was nightfall before he was released, bloody and bandaged, and he made his way to the running track where, in dusk and drizzle, fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol, as close to exhaustion as a fictional athlete can be, was still zooming round and round. Old Halob parped his whistle, and young Bobnit collapsed in a fictional heap upon the cinders.

“Great news!” shouted Old Halob, “Tomorrow you shall wrestle a real python, and the world will be agog!”

“Gack,” panted Bobnit Tivol, collapsing still further.

The next day dawned with more frost and ice and drizzle. Old Halob dragged his fictional protégé to the pole-vaulting practice pit and told him to practise pole-vaulting until such time as he returned bearing a python. The catarrh-racked coach then trudged off to the zoo, to find that it was shut, being a Friday. He soon discovered the menageries were likewise shut, and that following the tram crash of the day before, no trams were running. Passing the lamppost where he had seen the sign announcing the opening of the snakepit, he saw it had been altered, the opening having been cancelled by dint of civic pomposity.

“Where oh where am I to find a python?” wailed Old Halob.

At once, from the gloom of a gruesome nook, a figure appeared, like Harry Lime in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949). But he looked nothing like Orson Welles. His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion, and his straight black lips. His voice, when at last he spoke, was booming and monotonous, empty of human expression and lacking any variation in tone or cadence.

“You will find no pythons here,” he boomed, “But hie thee to the Bottomless Viper Pit of Gaar. There you will find vipers.”

And with that, the gruesome nook was again engulfed in gloom, and the figure vanished.

As he trudged to the railway station to catch the stopping train to Gaar, Old Halob wondered if perhaps, from time to time, a python might stray into the bottomless viper pit. Failing that, he supposed he could obtain a viper and disguise it as a python or, in extremis, rely upon the ophiological stupidity of the great unwashed. Spitting into a bramble-bush, Old Halob reflected that the masses, presented with the fantastic spectacle of a fictional athlete wrestling with a real snake, would be unlikely to worry their pointy little heads about precisely what kind of snake it was. He would say it was a python, and lo!, a python it would be.

It happened that the stopping train to Gaar stopped not only at every single damned station along the branch line, but also, repeatedly, in sidings, for hours and even days at a time. The delay thus caused was to prove fatal to Old Halob’s otherwise flawless plan. And flawless indeed did it seem when, arriving eventually at the bottomless viper pit, the man in the Homburg hat was greeted by the Duty Viperist, brandishing a net in which writhed a living python.

“What ho!” said this fellow, who bore a striking resemblance to Orson Welles, “I have just ennetted a python that had somehow strayed into the bottomless viper pit. Luckily, I spotted it while it was still near the top of the bottomless pit, otherwise who knows what manner of slithery hissy funny business might have transpired down towards the earth’s molten core. An asp got down there once and caused quite a kerfuffle among the vipers. But tsk tsk here’s me carrying on like a garrulous bon vivant good and proper! How may I help you on this frosty icy drizzly day in Gaar?”

“Give the python to me,” rapped Old Halob.

“I ought really return it to the Nest o’ Writhing Pythons just downaways past the viaduct,” said the Viperist, “But I have just had my breakfast and I am mad with cornflakes, so here, the python is yours.”

On the way back to Pointy Town, the stopping train stopped even more often than it had on the outward journey. But at last, long overdue, it chugged into the railway station. Old Halob retrieved the python from where he had stowed it in the goods carriage and trudged off in frost and ice and drizzle to the pole-vaulting practice pit. He was pleased to see that fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol was still, relentlessly, pole-vaulting ever higher and higher. He parped his whistle and the spindly youngster collapsed in a heap in the sandpit.

“Later today,” announced Old Halob, “Your name will ring out from sea to shining sea, and beyond, possibly even to planets and worldlets yet uncharted in the immensity of the boundless universe. Yes, fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol, you are to wrestle this python I have slung around my shoulders. At the moment it is in an induced coma. But I shall awaken it as soon as I have rented a large canvas tent and a wrestling ring and put up posters and sounded a klaxon to bring the great and the good and the hoi polloi in their teeming masses to witness a spectacle unlike anything the world has seen since 1877 when Sir Frederic Leighton unveiled his sculpture Athlete Wrestling With A Python! Think of the fame that will accrue to your spindly frame as you overpower the vicious serpent and crush it beneath your fictional running spikes! I feel sure your image will appear on cardboard breakfast cereal packets and you will be invited to open fairgrounds before this day is done!”

“Gack,” panted Bobnit Tivol, collapsing still further.

Half a century later, we might still be babbling excitedly about Old Halob’s visionary doodah. The tent and ring were rented, the posters put up, the klaxon sounded. The python was woken from its coma and placed in a ringside python-holding-unit of netting and bamboo. Fictional athlete Bobnit Tivol was limbering up in his fictional ringside limberarium. Puffing on his high tar cigarette, Old Halob looked out from the tent flap, expecting to see the teeming throngs come hurrying across the fields, an excited hubbub. Yet the fields were deserted, apart from a few dejected and immobile cows.

Such had been the delays occasioned by the stopping train to Gaar, on its wheezing journeys there and back, that frosty icy January had turned to frosty icy February. And today it was the sixth of February 1958, and the news had swept across town of the Munich Air Disaster, and the deaths of the Busby Babes, and all of Pointy Town was in mourning. On such a black day for sport, the last thing anybody wanted to see was a fictional athlete wrestling with a real python.

On a vernal equinox visit to the Vatican Museum in 2007, I was delighted to see the self-same statue of Laocoon and his sons being killed by sea-serpents which had been depicted in my school Latin textbook of Virgil’s Aenead. So delighted was I, in fact, that I took this photograph of it:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/gruts/439621251/

A short while later, I saw a second copy of the statue in the Uffitzi Museum, Florence.

The passage where Laocoon and his sons are attacked by the sea-serpents is, I recall, a very difficult one to translate effectively from the Latin. It contains an awful lot of words meaning coily and slithery and sinuous and lithesome and stuff like that.