In Brain Men, his splendid book about the British obsession with pub quizzes, Marcus Berkmann refers to the Gleam of Certainty. If, upon hearing a question, one of your team-mates exhibits the Gleam of Certainty, there is no need to debate possible alternative answers. Your team-mate knows the correct answer, beyond all doubt. Even if you think you know different, you must defer to the Gleam of Certainty.

I don’t much go to pub quizzes these days, but when I did, I waited in vain for one particular question which, had it been posed, I could have met with the Gleam of Certainty. But oddly enough no quizmaster ever asked it.

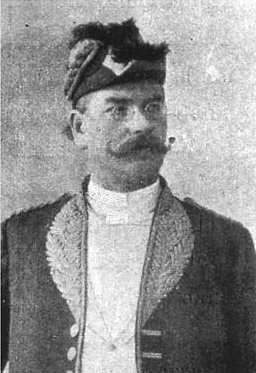

“Who,” I dreamed of hearing, “designed both the waterworks and the cupola of the Observatory in Berne, Switzerland, made a pair of shoes and a rifle for Haile Selassie’s uncle, sported Ruritanian tinpot attire, and was a pal of Arthur Rimbaud?” While everyone else scratched their heads and dribbled, I would have the Gleam of Certainty. For I know that the answer to the question is Alfred Ilg.

Ilg (1854-1916) – or rather, his surname – first struck me because I thought it sounded just like the kind of surname I would have devised for a Hooting Yard character, particularly in stories written in the pre-Wilderness Years of the past century. Ilg would have fitted in very well among Bewg and Ack and Vug and Fig and Mat and Nat and Bam and Lip and Obb and Pew and all those other curt monosyllabic names of which I was so fond. When one considers, too, that he created, from scratch, a functioning postal system, including the design of the stamps, it becomes apparent that, had Ilg not existed, I might have had to invent him.

Though he was born and died in Switzerland, Ilg spent many years in Ethiopia, working directly for King Menelik, the uncle of Ras Tafari, later Haile Selassie. It was the Ethiopian postal system he created, as well as its unified currency. He is considered to be the most important European in Ethiopian history, a sort of right hand man or, we might now say, chief of staff to the King. Arriving in what was then Shawa with his alphabetically extreme Swiss colleagues Appenzeller and Zimmermann in 1878, the first task he was given by Menelik was to make a pair of shoes. So delighted was the King with the result that he next asked Ilg to make him a rifle. Ilg protested that he knew not a jot about the manufacture of firearms and, perhaps with an eye to his later dealings with the gun-runner Rimbaud, suggested that imported weaponry would be far more efficient than anything he could cobble together. Menelik, being a big tough omnipotent king, swatted these objections aside and insisted that the Swiss shoemaker make him a damned rifle, pronto. Ilg, who clearly knew a lot more about rifle-making than he let on, duly made what has been described as a “passable rifle”. Perhaps Menelik tested it by taking potshots at passing Ethiopian wildlife. What we do know is that the King was so pleased with his new, lethal, toy that he gave it pride of place in his armoury and ever after considered Ilg indispensable. Indeed, some years later the Swiss with “the cuboid head and the scrubbing-brush hair” was given the splendidly uncertain title of Counsellor In The Range Of An Excellency, before eventually, from 1897 to 1907, becoming the rather more clear-cut Ethiopian Minister Of Foreign Affairs.

Though I am fond of his postal system innovations, Ilg was more celebrated in his adopted country for his civil engineering projects, including a major railway line, the electrification of the royal palace, and the design and construction of the piped water supply to the brand new capital of Addis Ababa. The latter has been described by Richard Pankhurst (son of Sylvia and great-nephew of Emily) as follows:

In 1894, Ilg installed the water installations for the Emperor’s palace at Addis Ababa. This created something of a sensation, as the water, obtained from a spring in high Entoto, had to flow down to the Addis Ababa plain beneath it, and then make its way up again to the Palace compound, which was located on a smallish hill. People in the capital had never seen anything like this, and could not believe that water could ever, under any circumstances, flow upward. Menelik, however, was a great believer in innovation, and insisted that Ilg should proceed with his project, if only to see whether it would work. When the great day for inauguration arrived, the tap was turned on – but nothing happened. A European “friend” had secretly stuffed cotton into the pipe, as Ilg later discovered. This obstruction was duly removed, after which Ilg – and his project – were widely acclaimed. At least two Amharic poems were composed in honour of the event.

One declared:

“We have seen wonders in Addis Ababa.

Water worships Emperor Menelik.

O Danyew [i.e. Menelik] what more wisdom will you bring?

You already make water soar in the air!”And the other ran as follows:

“King Abba Danyew, how great is he becoming!

He makes the water rise into the air through a window.

While the dirty can be washed, and the thirsty drink.

See what wonders have already come in our times.

No wonder that some day he will even outdo the Ferenje {i.e. Europeans].”

Neither of these poems was the work of Ilg’s friend Arthur Rimbaud, who by the time of their acquaintanceship had long abandoned poetry and was, in the final few years of his life, bitter and disillusioned. In 1888, he wrote:

I’m always very bored, in fact I’ve never known anyone be more bored than I am. And isn’t this indeed a miserable existence, without any family, without any intellectual activity, lost in the midst of these negroes whose lot one would like to improve, and who themselves seek to exploit you and to prevent you from realizing any money without long delays? Obliged to speak their gibberish, to eat their dirty food, to endure a thousand frustrations on account of their laziness, their treachery, and their stupidity. But that’s not the saddest thing. What’s worse is the fear of becoming brutalized oneself, little by little, isolated as one is, and so far away from any intelligent society.

It was not a view shared by Alfred Ilg himself, who thrived in Ethiopian society. As he wrote to Rimbaud in 1889:

It seems the delights of doing business here have driven away completely the little bit of good humour you had left. Look, my dear Monsieur Rimbaud, you only live once, so make the most of it and to hell with your heirs.

Ilg eventually returned to Switzerland, to Zurich, in 1907. He died there, of a heart attack, in 1916, on the seventh of January, which Pankhurst tells us was Christmas Day in Ethiopia.

NOTE : The quotations from letters by Rimbaud and Ilg are taken from Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud In Africa 1880-91 by Charles Nicholl (1997).

Alfred Ilg / glad rifle / rag-filled … his Ethiopian achievements in a nutshell …