I have not yet listened to it, but thanks to Strange Flowers I learn that the BBC recently broadcast a radio documentary about Arthur Cravan. This is the kind of thing that justifies the licence fee. But hurry! hurry!, it is only available until 12.00 AM on Thursday 1 January 2099!

Category Archives: Things I Have Learned

Italian Poisoning Cases, No. 1

The man admits putting poison in his wife’s water but denies trying to kill her. He told police he had been trying to make her a little unwell to ease her obsessional interest in planning pilgrimages and listening to the Catholic radio station Radio Maria.

from today’s Grauniad

Knitting And Catastrophe

“Knitting And Catastrophe In The Cinema”. Who could resist a talk with such a title? Certainly not me, which is why I pranced majestically through the south London streets in freezing temperatures yesterday evening to go and listen to Jonathan Faiers explain all.

Unfortunately, Dr Faiers turned out to be an academic, so his talk – which contained some interesting and intriguing snippets – was couched in dreadful brain-numbing postmodern gobbledegook. I realise that to carve out a career in modern academia you have to talk and write like that, but how one yearns to hear a simple, straightforward sentence! Instead, it’s all “discourses interrogating notions of the Other”, blah blah bollocks. I think “interrogate”, in its various forms, popped out of Dr Faiers’ mouth half a dozen times in little more than twenty minutes. I would happily have subjected him to a proper interrogation, tied to a chair in a secret police basement with a Klieg light shoved in his face.

Things were not helped by the fact that he was unable to master the technology to show us the film clips with which he meant to illustrate his blather. These would have included scenes from The King Of Comedy (Martin Scorsese, 1983), Breakfast At Tiffany’s (Blake Edwards, 1961), Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968), and Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944). You see what I mean? It could have been very interesting indeed.

In spite of all, I do applaud Dr Faiers for his title. “Knitting And Catastrophe In The Cinema” deserves its place in any list of highly amusing academic studies, alongside the one I devised thirty years ago, in tandem with my then colleague, the journalist and television person Tracey MacLeod. We planned to insert, in a bibliography, reference to a paper entitled “Topiary And Miscegenation In Contemporary Cinema”. Alas, it never appeared, for reasons I cannot now recall.

Birds And Bolshevism

I am indebted to Ruth Bosch for drawing to my attention this photograph from Paraphilia Magazine, captioned “Russian children taking part in a parade celebrating birds helpful to farming, 1934”. It is instructive to realise that Soviet Communism was not an unalloyed disaster, at least in ornithological terms. Needless to say, I am agog to learn precisely which birds were deemed “helpful to farming”. Skylarks? Peewits? Pratincoles? Any readers equally expert in birds and Bolshevism should contact me immediately.

You Can Buy God

In the song “Joe The Lion” on his ‘Heroes’ album, David Bowie tells us that “You can buy God”. I had always thought he was spouting twaddle, and pernicious twaddle at that, until I saw, in a New York shop window, the baby Jesus for sale, with a price tag tied to his elbow. Alas, the shop was shut, and I was unable to make purchase.

Pierre’s Bird Breakfast

after darting from where he sat a few invigorating glances over the river-meadows to the blue mountains beyond, Pierre made a masonic sort of mysterious motion to the excellent Dates, who in automaton obedience thereto, brought from a certain agreeable little side-stand, a very prominent-looking cold pasty; which, on careful inspection with the knife, proved to be the embossed savory nest of a few uncommonly tender pigeons of Pierre’s own shooting.

Herman Melville, Pierre, or The Ambiguities (1852)

Dispensing Irrelevance

As somebody who refuses to carry a mobile phone, I found myself nodding in agreement with this passage from Simon Raven’s memoir Boys Will Be Boys. He was writing half a century ago, in 1963, about what we now call old-fashioned “landlines”, but how right – and prescient – he was:

Cheap and easy systems of communication simply promote cheapness in what is communicated. If people have to pay 5/- for a telegram or take the trouble to write and post a letter, they think twice before they bother you at all. If they have a telephone, however, even the most trivial information takes on urgency. The telephone dispenses irrelevance like a tap which won’t turn off; it is also a dangerous instrument of interference and even persecution; but like most other so-called amenities of modern life, the telephone is essential for dealing with complexities which the telephone itself has caused, and it is quick to assert its tyranny at the expense of those who, like myself, would ignore it.

No Actual Mention Of Dick Van Dyke

A very pleasing cryptic crossword in the Grauniad yesterday, where clues yielded the words SOUP, a COLLIE, FRIDGE, ELASTIC, EGGS, PEAS, HALITOSIS and MARY POPPINS.

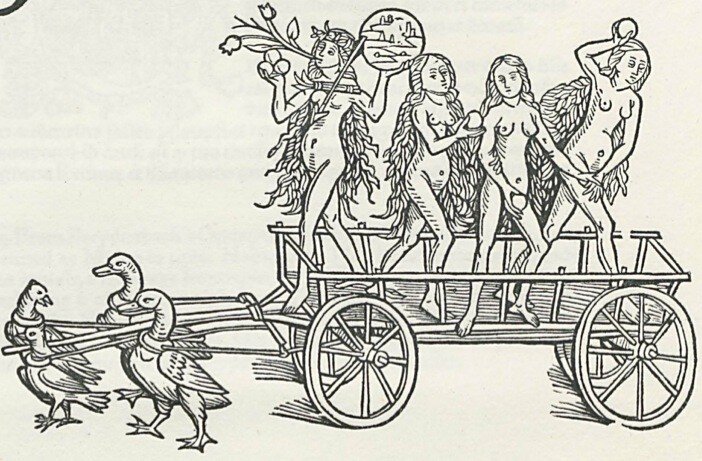

Venus Chariot

I am indebted to Richard Carter for drawing to my attention this woodcut he came across on Twitter, where it was given the caption “just a bunch of fruit-wielding naked women riding a duck-driven cart”.

Serpents

Emmett lived in a trailer park out by the airport. I took a back road and ran over a dead snake on the way. Louise turned to me. “You just drove right over that snake.”

“That was an old broken fan belt.”

“It was white on the bottom. Do you think I don’t know a snake when I see one?”

I told her he was already dead and that women were easily taken in by serpents.

Charles Portis, Gringos (1991)

Vile Mud And Weeds

From the archives, this postage first appeared seven years ago today, on 13 February 2006:

Almost exactly two years ago, on 13 March 2004 to be precise, our quote of the day was by William Hope Hodgson, from From The Tideless Sea. To jog your memories, he wrote

I am writing this in the saloon of the sailing ship, Homebird, and writing with but little hope of human eye ever seeing that which I write; for we are in the heart of the dread Sargasso Sea – the Tideless Sea of the North Atlantic. From the stump of our mizzen mast, one may see, spread out to the far horizon, an interminable waste of weed – a treacherous, silent vastitude of slime and hideousness!

When I chose the quotation I was unfamiliar with the work of Hodgson, a state of affairs which continued, shamefully, until just a few days ago. I am indebted to Tim Gadd for drawing my attention to this superb writer and encouraging me to immerse myself in the slimy, weed-choked pages of his books.

William Hope Hodgson (1877-1918) was an author, photographer, sailor, and body-builder, who wrote four novels before concentrating on short fiction. He was killed in the First World War. H. P. Lovecraft was an admirer, praising his “serious treatment of unreality,” and the critic Sam Gafford notes “his apparently inexplicable choice of writing styles” in an essay entitled Writing Backwards.

Reading his first published novel, The Boats Of The ‘Glen Carrig’, I was struck by something else ‘apparently inexplicable’. The story purports to be

an account of [the boats’] Adventures in the Strange places of the Earth, after the foundering of the good ship ‘Glen Carrig’ through striking upon a hidden rock in the unknown seas to the Southward, As told by John Winterstraw, Gent., to his son James Winterstraw, in the year 1757, and by him committed very properly and legibly to manuscript

so what we get is a thrilling yarn wherein the narrator recounts coming ashore in the Land of Lonesomeness. . .

we found it to be of an abominable flatness, desolate beyond all that I could have imagined… in the end, we found… a slimy-banked creek… the banks being composed of a vile mud

. . . before heading off to an island on a weed-choked sea where the bulk of the tale takes place. As in From The Tideless Sea, the setting is thus an interminable waste of weed – a treacherous, silent vastitude of slime and hideousness!

Lurking in the weeds are various disgusting creatures which our heroes fight off and outwit, in between doing boat repairs. But is there any other writer who would take pains to mention every single occasion his characters break off for a meal? Until the end, where several weeks’ action is summarised, the narrative takes us day by day, and Hodgson regularly reassures us that the castaways are getting proper meals.

I did some basic word-count analysis on the novel, and Hodgson’s focus of attention became clear. It is indeed a weed-choked book – weed, and enticing variants such as the weed-continent, appear 223 times (in a 60,000-word text). Considering that our narrator and his curiously anonymous pals spend much time in terror of the various disgusting creatures I mentioned, it is no surprise to find hideous, monsters, and tentacles accounting for a total of 51 words. Yet breakfast, dinner, and food win the day with 53. And as it seems de rigueur to have a puff after every meal, smoke is mentioned 15 times.

I have just begun reading Hodgson’s second novel, The House On The Borderland, and sure enough, by page three,

Tonnison had got the stove lit now and was busy cutting slices of bacon into the frying pan.

I hope an enterprising publisher reissues Hodgson’s works, if one has not already done so, but I would dearly like to see The William Hope Hodgson Recipe Book, a boon for any picnic-person in a silent vastitude of slime and hideousness!

A Virtual Prism

No More Soup, Ever

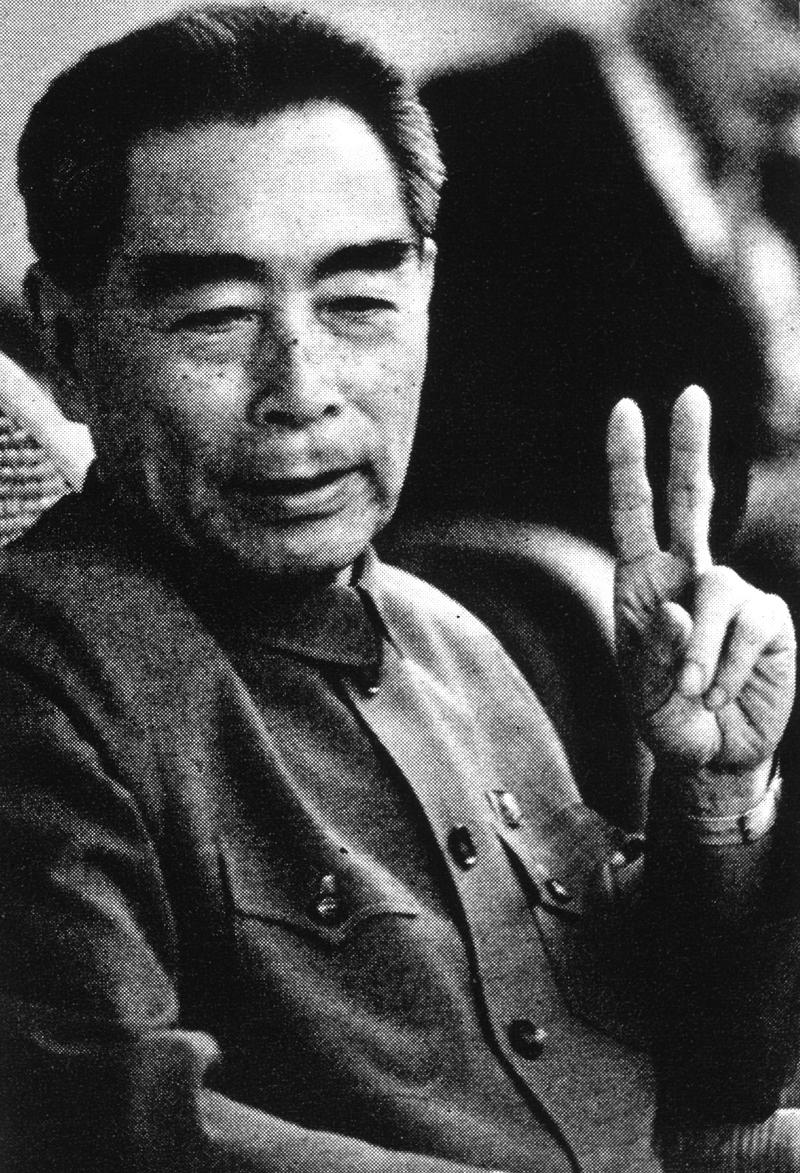

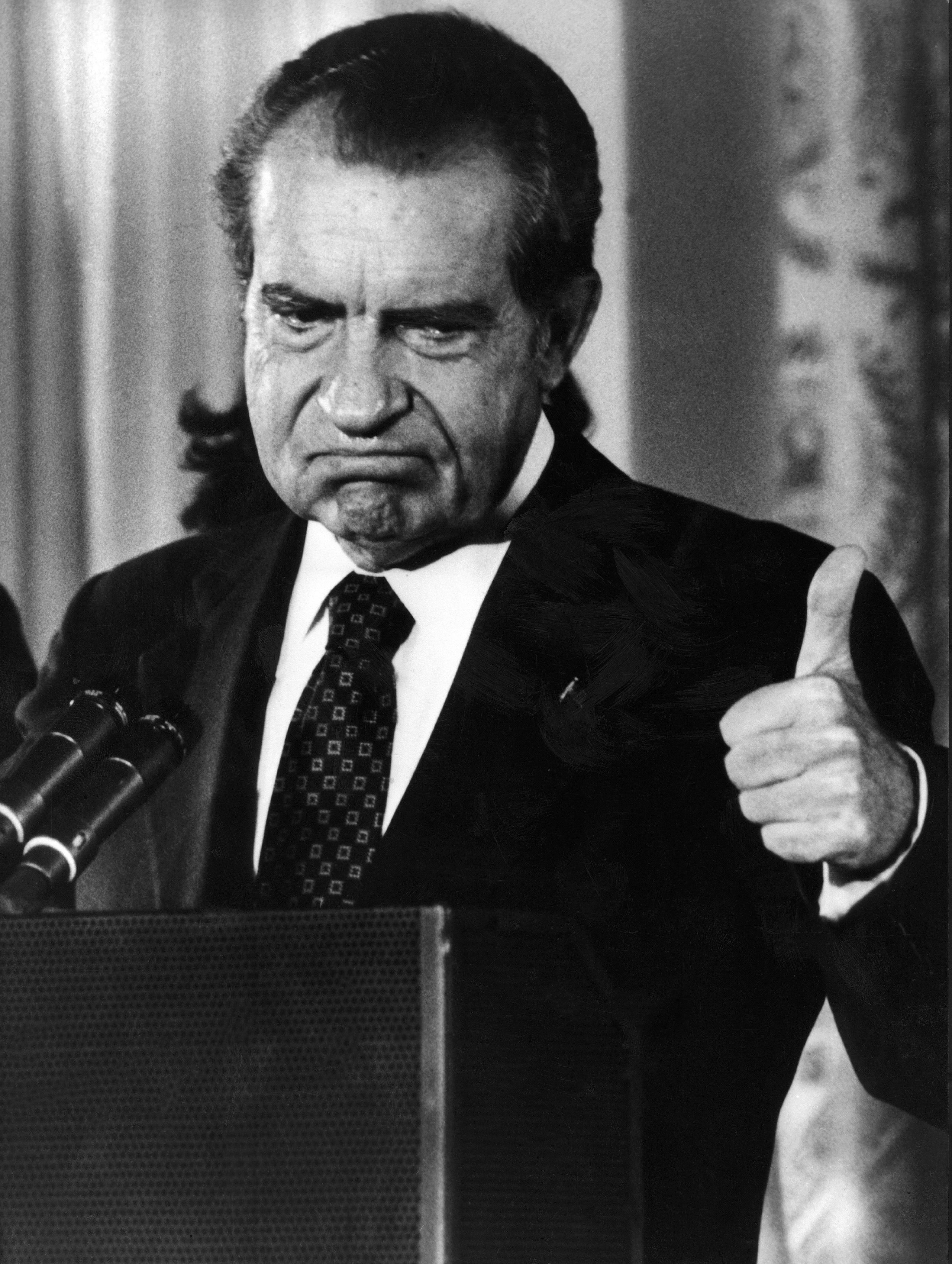

We already knew about Richard Milhous Nixon’s love of mashed potatoes. Now, thanks to Salim Fadhley, we learn of his diametrically opposite view of soup. Mr Fadhley pointed me to this passage from President Nixon : Alone In The White House by Richard Reeves (2001):

. . .on March 24 [1969], the President hosted his first state dinner, for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau of Canada. He complained to Haldeman about it the next morning : “We’ve got to speed up these dinners. They take forever. So why don’t we just leave out the soup course?”

“Well. . .” Haldeman began.

Nixon cut him off : “Men don’t really like soup.”

On a hunch, the chief of staff called the President’s valet, Manolo Sanchez, and asked : “Was there anything wrong with the President’s suit after that dinner last night?”

“Yes. He spilled soup down the vest.”

The action memo went out : No more soup, ever.

Credulous Nitwits

Malcolm Muggeridge describes “fact-finding” tourists to Stalin’s Soviet Union in The Thirties (1940):

Their delight in all they saw and were told, and the expression they gave to this delight, constitute unquestionably one of the wonders of our age. There were earnest advocates of the humane killing of cattle who looked up at the massive headquarters of the Ogpu with tears of gratitude in their eyes, earnest advocates of proportional representation who eagerly assented when the necessity for a Dictatorship of the Proletariat was explained to them, earnest clergymen who walked reverently through anti-God museums and reverently turned the pages of atheistic literature, earnest pacifists who watched delightedly tanks rattle across the Red Square and bombing planes darken the sky, earnest town-planning specialists who stood outside overcrowded ramshackle tenements and muttered: “If only we had something like this in England!” The almost unbelievable credulity of these mostly university-educated tourists astonished even Soviet officials used to handling foreign visitors.

Harold Nicolson’s Diary 31.1.32

Harold Nicolson’s diary, this day in 1932:

There is a dead and drowned mouse in the lily-pond. I feel like that mouse – static, obese and decaying. Vita is calm, comforting and considerate. And yet (for have I not been reading a batch of insulting press-cuttings?) life is a drab and dreary thing. I have missed it. I have made a fool of myself in every respect.

Surely there was a time I might have trod

The sunlit heights, and from life’s dissonance

Struck one clear chord to reach the ears of God?Very glum. Discuss finance. Vita keeps on saying that we have got enough to go on with. But when one goes into it, that represents only two months. I must get a job. Yet all the jobs which pay humiliate. And the decent jobs do not pay. Come back to Long Barn. Arrange my books sadly. Weigh myself sadly. Have put on eight pounds. Feel ashamed of myself, of my attainments, and my character. Am I a serious person at all? Vita thinks I should make £2,000 by writing a novel. I don’t. The discrepancy between these two theories causes me some distress of mind.