I ought to have posted this waxen image last week, to mark the changing of the year, but back then, in the past, I had never seen it. It’s a detail from “Time And Death” by Caterina de Julianis (1695-1742), a Neapolitan nun and student of the Sicilian abbot and waxworker Gaetano Giulio Zumbo (1656-1701). More here, though I came across it when reading the section on “Wax” in Marina Warner’s Phantasmagoria : Spirit Visions, Metaphors, And Media Into The Twenty-First Century (2006). Later on in the book I am looking forward to “Ether” and “Ectoplasm” – as, in the latter case, will be many visitors to this website. According to the statistics, more people come stumbling through the rusty iron gates of Hooting Yard in search of ectoplasm than of any other topic – not surprisingly, when we consider Marina Warner’s observation that “the gossip circuits of unofficial knowledge give the mental skyscape of the twenty-first century the wild heterogeneity of the Hellenistic world, as residues from different eras have adhered to form a sticky, bristling deposit. Judaeo-Cabbalistic angels; Gnostic energumens, phantasms and succubi; Neoplatonist daimons; Middle Eastern ghouls and genies; Romantic vampires and revenants; African, Caribbean, and Native American zombies and spectres – all these various spirits and more besides flock and throng the entertainment ether and the world-wide Web”.

Category Archives: Things I Have Learned

Art

As any fule kno, 99.9% of what passes for “art” in this witless age is mere piffle. As a rule of thumb, anything with the Charles Saatchi imprimatur can be safely consigned to the waste chute of history. It is also very probably true that anyone who describes themselves as an “artist” (as opposed to painter, potter, sculptor – emphasising the craft) is actually an idiot. Of course, it is the idiots who are showered with money and kudos.

In a brighter, more sensible world, some of the unknown amateurs tirelessly plying their crafts outwith the public gaze would be our stars. But then, perhaps it is because they are unknown and amateur and ploughing their own lonely furrows that their work is valuable.

All by way of preamble to egging you to delight in Outa_Spaceman’s latest project. Thus far, seven signs in seven days, marvellously enlivening his little south coast bailiwick. Saatchi ought to write him a cheque immediately – ah, but OSM didn’t go to Goldsmiths, and he doesn’t live in Hoxton, and he isn’t a wanker, so he must continue to ply his craft in obscurity. But we can celebrate it.

ADDENDUM : Some readers, seeing the heading “Art”, will have supposed this postage to be devoted to Mr Garfunkel, singer, poet, pedestrian and polymath. But according to his own website, he is known not as “Art”, nor even as “Mr Garfunkel”, but as “The G”.

Words Fail Me

A new edition of a Conrad classic, available here. Words fail me.

Tea

Now we have Christopher Hitchens in Slate telling us how to make a cup of tea, I look forward to the next instalment. John Pilger, perhaps, with instructions on how to boil an egg? No doubt the Pilge will explain that egg-boiling is an act of Zionist imperialist aggression, to be resisted at all costs by hard-hitting ill-argued whingeing, with a goodly dollop of manipulative sentimentality.

Hitchens’ piece is splendid, and has the added benefit of quoting Yoko Ono. She may, as he points out, be talking drivel, but every syllable that drops from her lips is to be treasured, as you well know, innit?

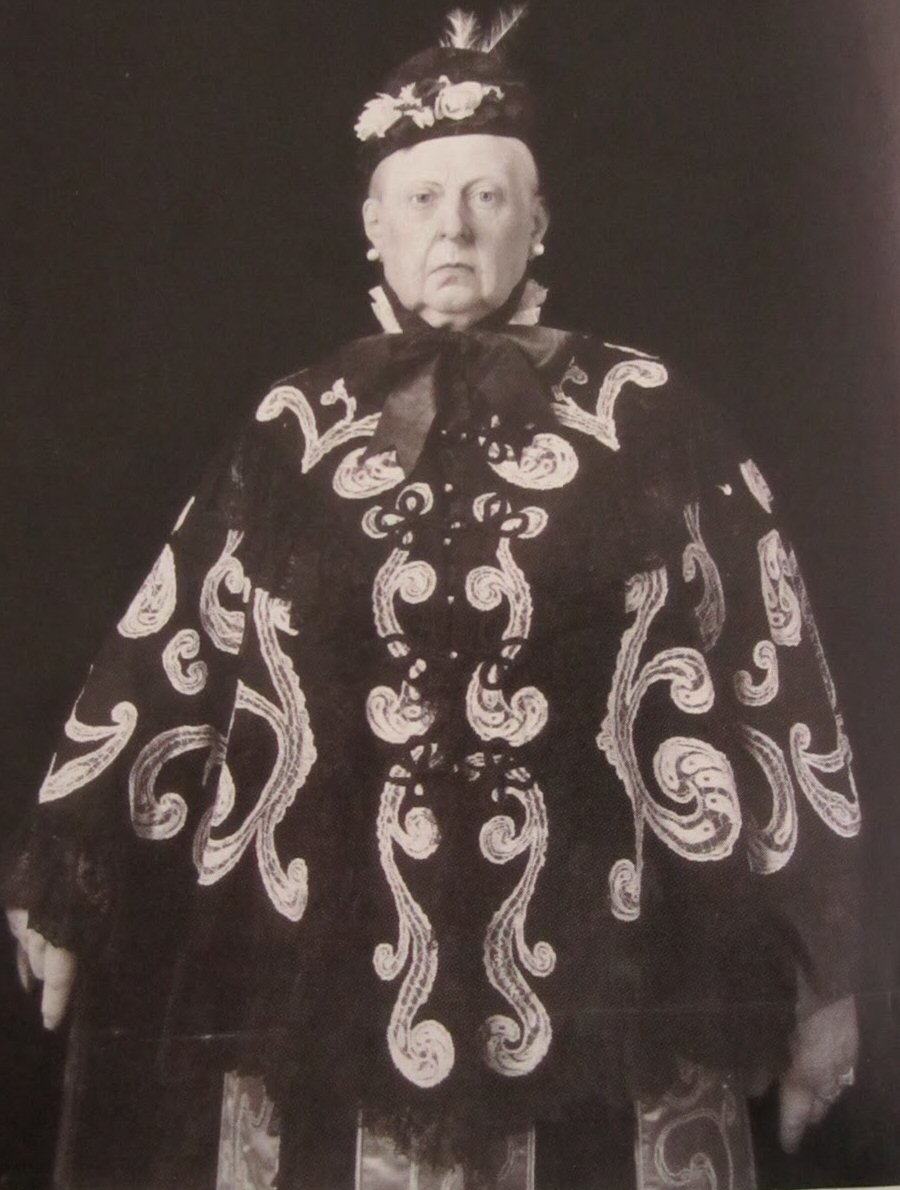

God Save The Queen

We must thank ZMKC for cutting out of a 2001 issue of the New Yorker this absolutely splendid photograph of Queen Victoria. I suspect that the Queen was channelling Madame Blavatsky, presenting herself as a mystic seer. Such garb should set an example to the royal personages of today.

Dogs & Frogs & Toad-Like Creatures

[Feb. 2, 1895.] I venture to send you the following story I have lately heard from an eye-witness, and to ask whether you or any of your readers can throw any light upon the dog’s probable object. The dog in question was a Scotch terrier. He was one day observed to appear from a corner of the garden carrying in his mouth, very gently and tenderly, a live frog. He proceeded to lay the frog down upon a flower-bed, and at once began to dig a hole in the earth, keeping one eye upon the frog to see that it did not escape. If it went more than a few feet from him, he fetched it back, and then continued his work. Having dug the hole a certain depth, he then laid the frog, still alive, at the bottom of it, and promptly scratched the loose earth back into the hole, and friend froggy was buried alive! The dog then went off to the corner of the garden, and returned with another frog, which he treated in the same way. This occurred on more than one occasion; in fact, as often as he could find frogs he occupied himself in burying them alive. Now dogs generally have some reason for what they do. What can have been a dog’s reason for burying frogs alive? It does not appear that he ever dug them up again to provide himself with a meal. If, sir, you or any of your readers can throw any light on this curious, and for the frogs most uncomfortable, behaviour of my friend’s Scotch terrier, I should be very much obliged. – R. Acland-Troyte.

[Feb. 9, 1895.] I think I can explain the puzzle of the Scotch terrier and his interment of the frogs, for the satisfaction of your correspondent. A friend of mine had once a retriever who was stung by a bee, and ever afterwards, when the dog found a bee near the ground, she stamped on it, and then scraped earth over it and buried it effectually -presumably to put an end to the danger of further stings. In like manner, another dog having bitten a toad, showed every sign of having found the mouthful to the last degree unpleasant. Probably Mr. Acland-Troyte’s dog had, in the same way, bitten a toad, and conceived henceforth that he rendered public service by putting every toad-like creature he saw carefully and gingerly “out of harm’s way,” underground. – Frances Power Cobbe.

From Dog Stories From The Spectator : Being Anecdotes Of The Intelligence, Reasoning Power, Affection And Sympathy Of Dogs, Selected From The Correspondence Columns Of The Spectator by J St Loe Strachey (1895)

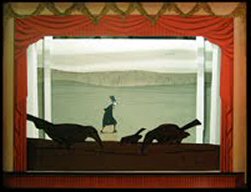

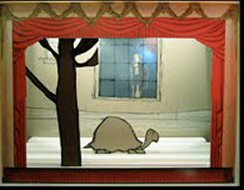

Theatrical Triumph

We do not pay much attention to the theatrical world here at Hooting Yard, unless, that is, we have tidings to report from the Bodger’s Spinney Variety Theatre. But every so often, a dramatic production so stupendous comes along that we can but gasp in awe and admiration.

Such a theatrical triumph is Entries From Reverend Gilbert White’s Diary In December, performed by Miss Hathorn’s Little Paper Theatre at Mustard Plaster. If there was a smidgen of sense in the world, this would transfer to the West End and pack in the punters and be showered with awards.

Readers are reminded that the Hooting Yard Christmas Special for 2009, devoted to Mrs Snooke’s tortoise Timothy (pictured above), can still be listened to here.

De Quincey’s Potato Anachronism

“Ah! what a beautiful idea occurs to me at this point! Once, on the hustings at Liverpool, I saw a mob orator, whose brawling mouth, open to its widest expansion, suddenly some larking sailor, by the most dexterous of shots, plugged up with a paving-stone. Here, now, at Valladolid was another mouth that equally required plugging. What a pity, then, that some gay brother page of Kate’s had not been there to turn aside into the room, armed with a roasted potato, and, taking a sportsman’s aim, to have lodged it in the crocodile’s abominable mouth! Yet, what an anachronism! There were no roasted potatoes in Spain at that date (1608), which can be apodeictically proved, because in Spain there were no potatoes at all, and very few in England. But anger drives a man to say anything.”

Thomas De Quincey, The Spanish Military Nun (1854)

The Faery Year

Listening to the hysterical news reports of our current snow-blanket, one might think we had entered a new Ice Age. But this too shall pass. As far as I recall, there are such things as seasons. For a sense of perspective, let us turn to George A B Dewar :

“At the acme of the year, days of great June with its clouds of endless forms and phantasies, wisp, stipple and fleece of cirrus and cirrostratus, snow mountains of cumulus; July with sorceries of silence and the scented breath of its eve, with its strange dance of ghost moths at dusk, when Capella is flashing intensely out of the afterglow and the gold taper of Mars is alight in the awful blue; August knee-deep in the copse grasses with yellow-hammer days; autumn with its golden-haired larches; winter with a wine-coloured withy wood by the estuary, and the ghost-like earth-cloud, stratus, creeping over the darkening marsh or heath; and at the same seasons the whirling columns of winter-gnats and the glittering gossamer weighted with rainbow dewdrops. Then there is the faery year of our English birds : spiral evolution of linnets in the frosty skies, loop of the rooks going home to rest, a flock of starlings in autumn black-budding the ash tree a field away, swans angel white clipt out on the leaden lake, thrushes singing like mad in the grey stormy March dawn.”

It is surprising, perhaps, to find that an English nature writer in the first decade of the last century was some kind of proto-Stalinist, but then there is this :

“The right enjoyment and study of these things must make men and women happier, completer in understanding in taste and eye, and therefore better members of the State.”

Quotes from the prefatory note to The Faery Year by George A B Dewar (1906)

At The Seaside

“I used to go to the seaside on holiday and expect beauty : now I observed more closely the infinite cruelty and indifference of the sea.” – The “religious cobbler” in The Professor by Rex Warner (1938)

“The sea is harder than the land.” – Dermot Todd, Filth (1987)

The Consumptives’ Cave

“It occurred to a medical man some years ago that the uniform atmosphere of this cave might be a specific for consumption.

“Possessed with this theory, the doctor had a dozen small houses constructed in the cavern, about a mile or two from its mouth, and to these he conveyed his patients. From the appearance of these places of abode, the only wonder is that the poor invalids did not expire after twenty-four hours of residence in them. They, however, contrived to exist there about three months, most of them being carried out in extremis. The houses consisted of a single room, built of the rough stone of the cavern, – which, in this part, bears all the appearance of a stone-quarry, – and without one particle of comfort beyond a boarded floor, the small dwelling being constructed entirely on the model of a lock-up, or ‘stone-jug’. The cells of a modern prison are quite palatial in comparison with them. The darkness is such as might be felt; and it is impossible to realize what darkness actually is until experienced in some place where a ray of sunlight has never penetrated…

“The houses – or rather detached stone boxes – were so small that without vitiating the air only one person could remain in them at one time; so that, besides the darkness, – in case of any accident to their lamps, – these poor creatures must have endured utter solitude. Their food was brought from the hotel, two or three miles away, on the hill, and consequently must have been cold and comfortless. They were kept prisoners within their narrow cells, for the rough rocks and stones everywhere abounding rendered a promenade for invalids quite impracticable. The deprivation of sunlight, fresh air, and all the beauties of the earth must have been the direst punishment imaginable. No wonder these poor creatures were carried out one by one to die.

“The last one having become so weak that it was deemed unsafe to move him, his friends resolved to stay with him in the cavern till the last. What transpired is now beyond investigation. Whether some effect of light, which in this cavern has a most mysterious and awful appearance, or whether the death-bed was one of terrors, owing to some imp of mischief having laid a plan to ‘scare’ them, as they say in this country, is not known; but they rushed terror-stricken from the cave, and on reaching the hotel fell down insensible. Subsequently they declared they had seen spirits carrying away their friend. Mustering a strong force, the people from terra firma, with the guides and plenty of torches, sallied down to the lower and supposed infernal regions. The spirits, however, had fled, leaving nothing but the stiffening corpse of the poor consumptive. This ended all hope of the cavern as a cure for consumption.”

Thérèse Yelverton, In The Mammoth Cave, collected in With The World’s Great Travellers, Volume One, edited by Charles Morris and Oliver H G Leigh (1901)

R.I.P.

Alas, it seems this must now serve as a posthumous tribute.

Talking Next To The Sea

“It is true that he spoke our tongue incorrectly and in an anglicised way, like all those whose mouths are more accustomed to chewing anglo-saxon pebbles and to talking next to the sea.”

Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly, On Dandyism And George Brummell (1845), translation by George Walden (2002)

The Teenpersons’ Guide To Hooting Yard (Part Two)

As promised, here is the second batch of teenpersons’ meditations upon Hooting Yard:

This story, To knit knots, peradventure, is probably aimed to be a funny piece of writing, and if read aloud, a tongue twister. The story is though, rather repetitive and after reading the first two paragraphs it starts to become all about the same thing; knitting a knot without being caught/seen by a hurrying brute. This piece is repetitive but is in no way boring; the many ways to knit a knot and not get caught by a hurrying brute is probably mostly but not completely nonsense, such as “Thus the knitter of knots is advised, in many books of the past, to find a secluded haven in which to knit”. Honestly if I were the knot knitter, I would have given up after the numerous attempts of knitting a knot without getting caught by a hurrying brute. The narrator doesn’t seem to describe each character much, though in a way it doesn’t really matter to the piece at hand. From what is given we cannot make out who (or possibly what) the knot knitter is, only that he/she is knitting a knot of value, or I doubt a brute would trying to get his/her/its hands on it.

This is a very descriptive piece including many words that may not be understood by children; words such as deftness, paragons and obviating. I think that this story was based on a ridiculous idea, and that would never happen, even though the actual writing is a creative piece and funny to read.

The main character is either the knitter of the knot or the hurrying brute, the knot knitter in this story is advised to do many a thing before he starts to knit a knot. The hurrying brute is the reason for the many reasons why you need to find a secluded haven such as a cave, behind ramparts or a towering fortress. The way the author talks is in some way appropriate for the story, as the knot knitter is trying to get away from the hurrying brute to find a place to knit. Although in the real world I doubt a hurrying brute would try to stop you from knitting a knot in the first place, and I wonder if there even such thing as a hurrying brute. Even though the knot knitter is hurrying through what seems to be a forest (full of hurrying brutes), he seems remarkably calm even if a brute is chasing him.

The books of the past (read before being chased by a hurrying brute) refer to the somewhat troublesome task of knitting a knot of peculiar knitting styles. Therefore the safe house in which you confine must be particularly safe and secure so as you may not be bothered with the hurrying brute. The only real problem when knitting a simple knot is when the brutes come in swarms, then the knot knitter is advised to abandon the knitting of his knot and run, even if the knot you are knitting is of particular value. If being chased by a swarm of hurrying brutes then the knot (if particularly prepared in their work) to have a missile at hand so to distract knitter is advised the hurrying brute, and so is able to find another rampart or clump of brambles to continue their knot knitting.

The tone of this piece is rather unusual and bizarre, and not something that you’d normally be reading in a story. It has some rather odd language, for example ‘It remains the case that the knitted knots has its own special place in our hearts, whether our hearts flutter like a bird’s or a squirrel’s heart, or pound like a drum’. I don’t understand the point of including information on a squirrel’s heart, as nobody knows (or even thinks about) why or how a squirrel’s heart beats. It goes off of the point a lot of the time (and some of the time I don’t know what the point is anyway!). Knot knitters do not exist so there is no point. I think this is just a comedy piece of writing and is written just for the laughter of others.

There aren’t any main characters; the story just generally talks about knot knitters and Brutes hurrying by and saying that hurrying brutes can never have the time and patience of a knot knitter. Brutes don’t exist in our world which is why this story is more a comedy sketch than fact and fiction.

Imitation

People don’t understand the experience and challenging expertise needed to become a knot knitter, but all of those people are hurrying brutes ignoring the precision used by the knot knitters needing peace and quiet to knit their knots in a very secluded environment. A plethora of noise is made by the hurrying brute which agitates the civic knot knitters that try to accumulate on the knot they are knitting.

That Awful Mess At Sludge Hall Farm

I feel that the story of “That Awful Mess at Sludge Hall Farm” is an odd and imaginative creation. For example “No-one knows the name of the farmer of Sludge Hall Farm. He is a hermit and a mystic and a pole-vaulting champion.” And as well as this, the story is peculiar and a bit out-of-the-box in the way that it mentions things that nobody would normally think of or about. For example “the farmer still pole-vaults every day, morning and evening, under the leaden sky at Sludge Hall Farm. He is puffing from a pole-vault as the Italian detectives push open the gate and greet him.”

I think this story is weird because it often strays from the point as this example shows, “One does not meet with a trio of stylishly dressed Italian police investigators tramping up the path to Sludge Hall Farm. In their Giuseppe Fonseca suits and Boffo Splendido shoes.” It has a bit of a magical feel as if things were very peculiar at Sludge Hall Farm as the farmer is a “mystic, a hermit and a pole-vaulting champion” and the story sometimes talks about the farm as if it is magical. For example, “One wonders what will happen. Will the farmer of Sludge Hall Farm speak for the first time in twenty years? Will he use his mystic powers to crack asunder the close-knit and almost telepathic team spirit of the detective trio, until they are snarling at each other like mad dogs and fighting with pitchforks?” and “Will the farmer placate his mutant pig and place it in a trance? Why is the hay in the hayloft not like normal hay? Is it hay from another dimension, or from somewhere else in the space-time continuum?” I think this is funny because most stories now include things from dungeons or mars like the monster from mars but this story uses a hayloft and the hay inside it with a mutant pig as the monsters.

I also think that the feel of the story is a sort of satire of what things are and what some things are becoming. Maybe for instance the hay in the hayloft could be a satire on what farming is turning into, the use of chemicals to create food that is now very different and much fuller of chemicals than it was 100 years ago. And the mutant pig that has snapped its chain could be a satire on guard dogs and the fact that they are getting more and more aggressive as their owners are getting more and more inhumane.

The feel of this piece of writing is amusing and strange, ‘If on the other hand, the hoofprints are still there, clamber on to a step ladder and try to obliterate them with a rag and a proprietary cleansing spray such as Hoofbegone!’. This part of the guide starts off and if sounds normal and then you get to the spray what is called ‘Hoofbegone’ and you think that it’s a tad strange because the name of the cleaning product is a bit odd because you have never thought of a product called something like that before.

The advice that the writing gives you is funny but serious, it is funny because the things it is telling you to do are amusing such as, ‘Try to recall any dreams you may have had while you were asleep. Did any hooved beasts, such as goats or horses, feature in these dreams?’ but then at the same time it is serious because if you do wake up with hoofprints on your ceiling, it’s a serious matter and you would follow this guide. When you start to read this you start to think how weird it is, and you think it is sarcastic because you don’t normally think you are going to wake up and there are going to be hoofprints on your ceiling, but then after you read the first paragraph you get hooked to the guide and don’t want it to stop.

There are no main characters as such in this writing. It is a guide so the author is aiming it at the people who wake up one morning and find hoofprints on their ceiling. It is written in first person so the author is telling the story. Nowadays we get step-by-step guides, such as ‘how to get a wasp’s nest out of your loft’ or ‘how to put a washing line up’. But if you saw this guide you would be amazed because you wouldn’t think you would see hoofprints on your ceiling, also if you saw this guide you wouldn’t believe that it would actually happen, many thoughts about the matter would be going through your head and it would be a serious matter. Also if you did have hoofprints on your ceiling you wouldn’t expect to go out to the supermarket or some sort of shop and expect to find a guide of what to do in that situation.

Extension

If you do wake up and there are hoofprints on your ceiling and you have already been and seen the local nocturnal hoofprint investigation specialist, ask the woman at the reception of the office for ‘The Potion’ and make sure you do anything to get that unique potion this special drink form of a potion will make you turn upside down, when you have got the drink go back to your room and gulp the drink down and then take a quick stroll across the ceiling and follow the hoofprints until you find out who or what has done this. If the trail goes on and on and you potion has run out, go back to the local hoofprint investigation office and tell the same woman at the desk that the potion wore off and that first, you would like a refund and second that you need the papers to sue the specialist, if the woman refuses to give you the papers just ask for a emergency appointment with the local nocturnal hoofprint investigation specialist again.

The Muscular Fool And The Other Fool

The story comes across as being quite a funny story as it is about a ‘fool’. It starts off with the line ‘a fool dug a hole in the ground with a spade’; I think this a strange beginning but it does make you want to read on.

The person in this story immediately comes across as being quite stupid as the first thing he does is dig a hole and sit in it. The author of this book is clearly quite strange like the character. The character throughout does many strange things such as above dig a hole just to sit in and then go in an escalator just going up and down all day being fascinated by them.

I spent 20 minutes on this piece of work.

Confessions Of A Door To Door Monkey Salesman

This story is a ‘Bildungsroman of fierce intensity’, as it says at the beginning, because it follows the development and maturing of the lead character. I found this story very odd because it was about an orphan, adopted by some pig farmers, who was taken under the wing of a ‘countryside rascal’ to become a door to door monkey salesman after his adoptive parents perished in the ‘Munich air disaster’. As you can see here the plot is extremely bizarre and the world in which the story is written is mostly the same as ours but with small differences, for example: door to door monkey salesmen and ‘rascals’ which the main character searches for.

This story in also written in an interesting way, which is: one paragraph is written in the main characters point of view and then the next is written in the narrator’s point of view, reviewing what is happening in the story. The story takes a strange idea and imbeds it into our world, making the concept of a door to door monkey salesman not as strange an idea as first thought.

The story is written in first person; however, the writer describes you remembering yourself as a young child being very strange and irregular, ‘with your two thumbs, seven fingers and eleven toes’. Two thumbs in human terms is clearly very regular but the mother, whom is speaking to you at this point, goes on to talk about your ‘irregularity’ and says, ‘and you, my cherished tiny one, are one freakish anomaly,’

Another character is the ‘monkey rascal’, who is an old and is a man. It describes him as old when he says ‘and theses old bones of mine aren’t getting any younger.’ You can tell that the person is a man when the main character says ‘pausing now and then to sip his cocoa,’

Imitation:

I found myself one day walking down the cobbled street toward the house in which the man asking for monkey rental lives. It was an intriguing house made from the bricks of the dilapidated old habitation which once stood before it. The monkeys strolled behind me in tow not making a sound as they edged closer to the eerie setting. I must have looked very off-putting with my severe disfigurement and primates following along after me and so the townsfolk veered away from me as I ambled down the road. The man did not seem to be a rascal when I encountered him at his doorstep and confronted me with several monkeys behind him himself, he then said,

‘You are the monkey salesman.’ With that I replied I was and handed over the monkey to him. However, he rejected the monkey and told me to wait for him to retrieve something from his dwelling before accepting the animal …

This paragraph would be slotted into the story after he has been introduced to the monkey rascal and is on his debut monkey sale.

Character Flaw Of Mediaeval Peasant

I feel that the tone of this piece of writing is meant to be comical. This is because of certain lines in it, for example, ‘I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be. I don’t even know who Prince Hamlet is, or was, or will be, and I was always meant to be a peasant.’ The reason I think this line is comical, is because it is from TS Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, which means the character has obviously heard this line from somewhere, but doesn’t really know what it means, and is just trying to sound clever. ‘‘’Twas writ upon the stars.’ This line really does make the peasant sound stupid because he can’t speak properly and the line should say, ’Twas written upon the stars, and yet again I don’t think he knows what he is talking about. There for I feel the peasant is trying to sound clever, when he is just making himself sound stupid.

The character in the story is a mediaeval peasant called Cleothgard, who is trying to explain his character flaw, across the centuries. He tries to sound clever because he thinks people will think more of him but in fact he just sounds stupid. In the story he explains that his character flaw is, whenever a baron is approaching him he feels the need to out do all the people around him, by showing his appreciation, he says ‘A goodly number of them will tug their forelocks and dribble with happiness at the sight of him, but I feel this urge to outdo them. That is my character flaw.’

I think I am the only person with my character flaw. It is strange to have this character flaw but then everyone does have a character flaw. The thing is I try to outdo everyone but I really just act so stupid no one notices me. Yet I want people to notice me. I mean I don’t mean to do what I do and I try to stop myself, but somehow I just can’t. I have this uncontrollable urge to, whenever a baron is coming, to fall flat on face and bury my head in the mud.

My story is very strange and quite light hearted; the main character gets obsessed with a peasant who insulted him. I also think the story is about bullying because lots of people insult him and he says ‘I would have welcomed death’.

My paragraph

I have been impugned, many times a day, by the peasant with the greasy, matted hair. He calls me all the names under the sun. None of them are nice. I have become accustom to this impugning every day, until my peasant went away. I looked for him so I could impugn him, but he was gone, never to be seen again. I asked where he had gone but no-one seemed to know, was he going fast, slow, did he have greasy hair and horrid teeth. Was he dirty?

When I arrived home I started to build a peasant to impugn me; I started to build him from cardboard and wire mesh, a mechanical peasant to impugn me daily. I can still imagine the peasant, perfectly in my head, his greasy hair and horrid teeth.

The story sounds like it has been written for children in the way that the writer has described what happened. He has written the first part of the story about stealing bird seed, which isn’t like drugs or electricals. He also writes that he thumped the truck driver; instead he could have written that he stabbed him or held a gun to his head. This gives it the feeling of more of a children’s story about a post office robbery than an adult crime thriller.

There are only three people in the story who are named and only two of them appear more than once in it. These three are Blodgett, Detective Captain Cargpan and Mrs Gubbins. Blodgett is the main character in the story and it all revolves around him. He appears to be quite a clumsy man but is very well-built. He is a man that gets involved with heists and always manages to ruin it by not being observant, getting distracted or just acting a fool. Detective Captain Cargpan is not described in this story and only appears briefly in it, this is the same with Mrs Gubbins.

Seventh Heist. By now, Blodgett’s next heist has been widely publicised because of the report that the weekly heist intelligencer had in its last issue. The heist is supposed to take place in a well-known seaside resort by a very dangerous gang who is thought to have purchased a small amount of explosives. Because of this gang’s history of murder and manslaughter, the police have been called to surround the area.

I think the story is written in a serious way which made it quite funny. The man in the story is telling us about all his illnesses and accidents that he has had. I had to read this a few times to understand it properly because it is full of complex sentences and unusual language for instance, “the mountain, disgorging a miscellaneous collection of people.” The author does not put a very nice picture in my mind when they are talking about the Smem. The name ‘Smem’ makes it sound grotty and like an unpleasant place to visit. This is a clever topic because everyone can relate to being ill but it seems strange how he is always ill. It is quite long with lots of sudden flash backs to make the story more clear.

The main character is a man who had gone away to a place along the banks of the Smem a river. He seems to be reminiscing and telling us all about his life during the story. You never find out his name or much about him apart from storeys about his health. He is prone to hearting himself and has a very bad relationship with goat’s milk, he thinks it’s not safe and is very unhygienic. His illnesses are very unusual like when he says he had “leasio in testiculo” a type of disease in his testicles. This shows us how hard his life must have been. He has a peg-leg and he talks a bit about his religious hysteria which is quite intriguing.

Extension

When I was age eleven I twisted my spine in a boating accident. This was a huge shock to the system and took three months of physiotherapy to sort out. For two years I had a very strained Adams apple and a cracked nose. In the summer of 2004 I hade the most horrific illness that insisted on me waking up at 12 o’clock every night to be violently sick at least 4 times. I was later in danger of my guttural speech going and never returning. Now standing on the banks of the Smem I wonder if I was just handed a bad card in life and if I was really destined for greatness.

Frivolity

“Frivolity – The maddening name which is given to a whole series of preoccupations that are really entirely legitimate, corresponding as they do to real needs.”

Footnote in On Dandyism And George Brummell by Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly (1845), translation by George Walden (2002)