I have never given serious thought to the idea of reincarnation, and it is about time I did so. After all, we are serious people, are we not?, and we should think seriously about everything, absolutely everything, as it falls within our purview. There will be many subjects deserving of only our fleeting attention, but even those we should consider with all due seriousness. In that spirit, and in the full knowledge that the concept of reincarnation, or the transmigration of souls, is almost certainly arrant poppycock, let us see if we can winkle from it anything of significance.

In some versions of the theory, the transmigrating soul flits from species to species. This would suggest that, immediately before the glorious event that was the arrival upon earth of Mr Key, I might have been, say, a bat or a prawn or a tulip. This is a perfect example of something so foolish that our fleeting attention can fly away from it tout suite, with nary a backward glance. Like the collected written outpourings of Will Self, it can be safely tucked away and forgotten about. We gave it our serious attention, for a moment or two, and then moved on, sensibly, as sensible and serious persons do.

Of more interest is the idea that, as the spark of life is extinguished in one human corporeal being, at the very moment when life passes it makes a leap into a brand new host. Though as preposterous as the idea that I was once a tulip, this at least has a certain tidiness about it. If, for a while, we entertain the possibility of it being true, the urgent question then thumps inside our heads – who were you, Mr Key, before you were Mr Key?

I am minded to date the dawn of my existence not to the date of birth, but to the moment of conception in my mother’s womb. Unless one’s father is a precise and punctilious Walter Shandy figure, that moment is well nigh impossible to pinpoint, so the best we can do is to use informed guesswork. Counting backwards from the date of my (premature) birth, it is likely that I was conceived in the dying days of May in the Year of Our Lord MCMLVIII, or, as modern barbarians would prefer, 1958. So who shuffled off this mortal coil around that time, apart from several bats or prawns or tulips?

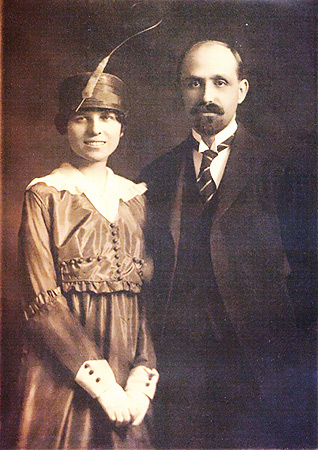

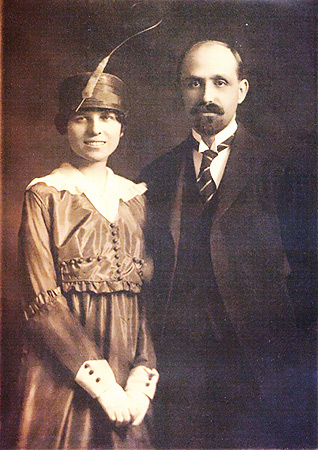

Three candidates present themselves – the Romanian aviator Constantin Cantacuzino, the Spanish writer Juan Ramón Jiménez, and – skipping forward slightly to the beginning of June – the American oceanographer Townsend Cromwell. The next stage of my serious research will be to immerse myself in the lives of this trio, finding out all I can, perhaps entering a fugue state. Without leaping ahead of myself, I have to say that my favourite of the three, at this stage, is the Spaniard, not so much on account of his Nobel Prize for Literature (1956), but because, judging by this photograph, his wife is wearing exactly the sort of hat I can imagine Pansy Cradledew sporting atop her lovely head.

I will keep you informed of my findings.