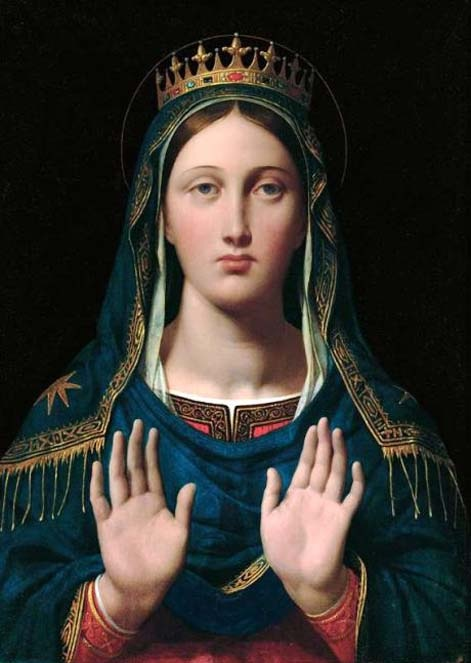

Every so often it’s important to sit and contemplate a picture of the BVM.

Monthly Archives: July 2012

On The Bisky Bat

The Bisky Bat was first identified by Edward Lear in his poem The Quangle Wangle’s Hat (1877). It would be more accurate to say that it was only identified by Lear, as nobody before or since seems to have had a word to say of its existence. Believe me, I have done the research.

The initial problem I had to solve was whether “Bisky” was part of the formal nomenclature of this type of bat, or whether Lear was referring to a generic bat, and applying a descriptive adjective. The capitalisation of “Bisky” would suggest the former, though “Bat” is also capitalised in the text, so who knows? If “Bisky” is a general adjective, it is one that has been neglected by the OED and by all the other standard dictionaries. There is a slim possibility that it may have something to do with biscuits, but it is hard to understand what might be biscuit-like about a bat. You might bake a biscuit in the shape of a bat, but that would be a Batty Biscuit, not a Bisky Bat. I concluded, after much furrowing of the brow and smoking quite a few gaspers, that “Bisky” was indeed the formal name of a type of bat.

My knowledge of the world o’ bats is breathtaking. One of my party pieces, which never fails to enliven even the most straitlaced and sober of social gatherings, is to reel off in a dramatic tone of voice a list of bats. I rarely need prompting, and I do not need prompting now. Some bats then: the Asian False Vampire Bat, the Asian Painted Bat, the Big Brown Bat, the Big Free-tailed Bat, the Brandt Bat, the Brazilian Free-tailed Bat, the Brown Long-eared Bat, the California Leaf-nosed Bat, the Common Yellow-shouldered Bat, the Daubenton Bat, the Desert Red Bat, the Eastern Long-eared Bat, the Eastern Pipistrelle, the Egyptian Fruit Bat, the Evening Bat, the Florida Mastiff Bat, the Fringe-lipped Bat, Geoffroy’s Rayed Bat, the Giant Indian Fruit Bat, the Golden Horseshoe Bat, the Gray Bat, the Greater Bulldog Bat, the Greater Horseshoe Bat, the Greater Long-nosed Bat, the Greater Spear-nosed Bat, the Hoary Bat, the Honduran White Bat, the Indiana Bat, the Ipanema Bat, Keen’s Bat or the Northern Bat, the Lappet-browed Bat, Leisler’s Bat, the Lesser Horseshoe Bat, the Lesser Long-nosed Bat, Linnaeus’ False Vampire Bat, the Little Brown Bat, the Long-nosed Bat, the Mexican Big-eared Bat, the Mexican Fruit Bat, the Nathusius Pipistrelle, Natterer’s Bat, the Noctule Bat, the Northern Yellow Bat, the Pallid Bat, the Parti-coloured Bat, Peters’ Ghost-faced Bat, Peters’ Tent-making Bat, Peters’ Wooly False Vampire Bat, the Pipistrelle Bat, the Pocketed Free-tailed Bat, the Pygmy Pipistrelle, Rafinesque’s Big-eared Bat, the Red Bat, Rodrigues’ Fruit Bat, the Seminole Bat, the Serotine Bat, the Short-tailed Fruit Bat, the Silver-haired Bat, the Southeastern Bat, the Southern Yellow Bat, the Spotted Bat, the Straw-coloured Fruit Bat, the Surat Serotine Bat, Townsend’s Big-eared Bat, Underwood’s Long-tongued Bat, Underwood’s Mastiff Bat, the Vampire Bat, the Western Mastiff Bat, the Whiskered Bat, the Wrinkle-faced Bat, and the Yellow Bat. This is by no means an exhaustive list. I have not mentioned, for example, the Demonic Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Veldkamp’s Dwarf Epauletted Fruit Bat, St. Aignan’s Trumpet-Eared Bat, the Strange Big-eared Brown Bat, Schlieffen’s Twilight Bat, the Tiny Yellow Bat, the Robust Yellow Bat, the Equatorial Dog-faced Bat, the Coastal Tomb Bat, the Buffy Flower Bat, the Hairy Little Fruit Bat, nor the various Smoky Bats. I could prattle on for hours, and perhaps include a diversion where I pointed out the amusing fact that an entire genus of fruit bats is known as the Dobsonia. But no matter how long my party piece lasts, the one bat you will not hear mentioned is the Bisky Bat.

Now this is very odd. Edward Lear was a formidable naturalist, and he would hardly have invented a bat. I can only assume that he spotted one, in 1877 or shortly beforehand, named it, wrote of it, and then went on his merry way, no doubt assuming other bat-mad persons would subject the bat to further study. And yet they did not.

Having reached a dead end in my researches, it occurred to me that I could make profitable use of my time by attempting to draw a Bisky Bat. Now it has to be said that I am a pretty cack-handed draughtsman, and not one of the hundreds of bat drawings I have made in the past bears much resemblance to a bat. I always have trouble with the wings and those little eyes and the complex radar-like navigation system bats rely on to get from A to B. But on this occasion it would not be “me” doing the drawing, for I resolved to enter into a trance and, with my arm suspended, from the elbow, in a sling, and a pencil glued to my fingers, I would commune with a spirit guide. This guide would control the movements of the pencil across the paper. Before sinking into the trance, by means of mystic Blavatskyan breathing exercises, gibberish, and a Brian Eno record, I went for a stroll and a smoke and I wondered if the spirit that communed with me would be Edward Lear himself, or perhaps another Victorian naturalist, one who had also spotted the Bisky Bat but had failed to recognise it properly, and was now taking the opportunity to make amends for his oversight. I would never know, of course, for when I emerge from these trances, my brain is as if wiped clean with a particularly effective disinfectant preparation.

The other thing that happens when I emerge from these trances is that I am confronted with a sheet of paper on which I, or the medium, has scribbled and scraped a formless mess of squiggly quangle wangle. I always forget that, too.

I have not quite abandoned my Bisky Bat research, however. I am now working on the theory that the editors of the OED, and of all other standard dictionaries, have somehow overlooked the word, and that it does indeed exist as a common adjective. All I need do now is to work out what it means.

On The Mutterings

The first I knew of the mutterings was when I overheard them, being muttered. A door was ajar, and I was in the corridor with my pail and my mop. Through the ajar door I heard the mutterings, but only for a few seconds, because suddenly the door was slammed shut, from within, presumably by one of the mutterers. I stood waiting awhile, in case the door might be opened again, but it was not, so I moved on along the corridor, towards the holy golden slab.

You might wonder what a holy golden slab was doing in the corridor of an otherwise nondescript municipal office building. Somebody once told me that the explanation was only given on a need to know basis. What arrant poppycock! I think that person was trying to intimidate me, or to put me in my place. I would dearly like to know if he was among the mutterers behind the now closed door. Well, I will find out, by hook or by crook. What either a hook or a crook would avail me in the circumstances I do not presume to guess. But there is always a nugget of wisdom to be found in common sayings, so perhaps one of these days I will go down to the basement and rummage around in the storage cupboards to see if a hook or a crook, or both, have been discarded there, at some point, by one of my predecessors. How I will then proceed I do not yet know. Perhaps it will come to me in a dream.

It was in a dream that I learned why the holy golden slab is where it is. It was vouchsafed to me by the night-time goblins that control our dreams that the holy golden slab has always been there, in the same spot, for as long as history. The building was built around it, you see. I think the holy golden slab was meant to be in a room all by itself, a locked room, but somehow the building’s blueprints were misinterpreted, and it ended up being at the end of a corridor. They could have put in some panels and created a room around the holy golden slab, shortening the corridor a little, but money ran out. Imagine that! Not enough money in the coffers for a few panels.

That was a hundred years ago, of course. I expect there is money for panels now, but everybody has got used to the holy golden slab being in the corridor, and it is no longer thought important enough to be hidden away in a room of its own. Funny to think that it was once an object of awe and trembling. I was awestruck and trembling when I saw it in my dream. But in the pitiless light of day, when the goblins loosen their grip on our brains, I, like everybody else, feel neither awe nor trembling. I mop the floor around the holy golden slab as a matter of routine, and once in a while I run a duster over it.

One of my predecessors put a tarpaulin over it, to save on dusting. The very next morning he was found in a dingy alleyway. His throat had been slit.

On my way down the back staircase to the basement, to pop my pail and my mop into a cubby, I began to wonder if the mutterings I had overheard were something to do with the holy golden slab. I had not been able to pick out individual words, in the few seconds of my overhearing, but an inkling nested in my brain and would not be dislodged. I wondered if the goblins of the night might tell me more, when my head was apillow. But they had nothing of relevance to impart. I dreamed of dogs barking in a rowing boat in the middle of a lake, and the crushing of a rebellion.

The next day I noticed that the door in the corridor was ajar again, And yes, as I stepped closer, I heard mutterings. This time I hoped I might be able to make out something of what was being muttered. Then I could rest easy, without having fantastic thoughts about the holy golden slab pinging round and round and round in my poor overheated brain. It needed a bit of mopping itself, were that a possibility. But again the ajar door was slammed shut when I had been loitering for bare seconds. Obviously the mutterers wanted to keep me in the dark. But how did they even know I was there? Mirrors, probably.

This went on for a week. The door was always ajar, and it was always slammed shut before I could hear clearly what was being muttered. As for the holy golden slab, no change there. But then there never had been any change, since the dawn of recorded time, or at least since time immemorial, which legally, as I understand it, is any time before the sixth of July 1189. As for me, I went on toiling up and down the corridor with my pail and my mop, I went on skulking down to the basement, and every night I rested my head on my pillow and bid the goblins start up their frolics in my sleeping brain.

What I did not know, and learned only later, much later, was that one by one the mutterers were found in a dingy alleyway with their throats slit. I found out all the grisly details when they arrested me, and charged me with the killings. Ever since that six in the morning hammering at the door, and the handcuffs and the blanket over my head, the night-time goblins have fallen strangely quiet.

Now, it is as if I have an empty head.

[And the above is the result of determinedly bashing out a thousandish words while in the grip of empty head, or vacancy between the ears, syndrome. Must do better.]

On The Ice Age

Brrrr! Wrap up warm, because it’s cold outside! Well, it would be, wouldn’t it, this being the Ice Age. There have been other Ages – Stone and Iron, for example, and Bronze – but this one we have dubbed the Ice Age, because it is so chilly. Sitting here next to my oil stove, wearing various furry animal pelts, it is easy to forget just how cold it is outside. I can’t see through the windows, because they are all frosted up, but I suppose if I turned down the volume on the cassette player I would be able to hear the howling winds of the blizzard, and they would serve to remind me of the cold. But I would rather listen to the cassette playing poptones, quite frankly. I am not in the right mood for howling.

The wind howls, and so do wolves. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish one kind of howling from another. Wolves seem to thrive in the chilly chilly weather of this Ice Age. They have furry coats of course, or at least hairy, bristly coats, au naturelle, as it were. To obtain my furry pelt I have to slaughter apt creatures, or at least pay someone to do so for me, to slaughter and skin and stitch. I am somewhat weedy, and short-sighted, and I would much rather huddle by the oil stove listening to poptones than be out there in the cold, hunting and stalking. In any case, I do not have a pair of snow shoes, so I wouldn’t get very far. Within a few feet of my door I expect I would be up to my waist in snow, and helpless, and I would have to make puny cries, in the hope that a tough wolf-hunter would come to my rescue.

At least you know where you are with wolves. Those rampaging wild boars are another matter entirely. Blimey. I have been woken from a nap by the sound of them battering their tusks against the walls of my hut. I am pretty sure it was a wild boar, covered in hoar frost, that chewed through the wiring of my radio set. I thought the wiring was safe, submerged under snow, stretching out across the tarputa, but those boars are relentless. Now I can only get some of the channels, and none of the music ones, which is why I rely on the cassette player.

Ice Age music is pretty grim, all told, but when the alternative is the howling of wind and wolves and the bashing of boar-tusks against the walls, you have to take what you can get. And it’s not all bad. I grew quite fond of Chepstow’s Icicle Symphony, for example. But the tape was ruined when I left it too close to the oil stove, and it partly melted. So now I make do with poptones, icy poptones, with lots of synthesizer. At top volume, it drowns out the howling.

I used to have a pair of snow shoes. Of course I did, for how else would I have been able to cross the tarputa and make it to my hut? It took me six weeks to get here, plodding slowly. I meant to hang on to them, for emergencies, but the fibre they were made from was highly flammable, and one evening the oil stove spat out a stray spark which ignited them. I acted quickly, putting on a pair of mittens and chucking the burning snow shoes out of the door, into a snowdrift. If I hadn’t, the whole hut would have burned down and I’d have been a goner. But it means that now I have to rely on passing wolf-hunters for certain essentials. They can be a difficult lot.

I got so fed up with the rampaging wild boars battering their tusks against the walls that I thought I’d fashion some kind of boar-trap. I asked one of the wolf-hunters for help. In return for soup, I hoped he would dig a pit outside, a few feet away from the door, into which the boars might topple, and having toppled, perish. The rascal ate my soup but said he was a wolf-only hunter, and couldn’t be distracted in his career by digging a pit for boars. He was huge and violent, so I didn’t argue.

I may no longer have the Icicle Symphony to listen to, but I have plenty of icicles. They hang from the ceiling, in their hundreds, and occasionally I pluck one off, to suck, or to use as a little spear. Sometimes I will use the same icicle for both spearing and sucking, turn and turn about, until my sucking has made it useless for spearing. The icicles are a bit too big to use as pins, and funnily enough I have discovered I have absolutely no need of pins, here in my hut. I have got along quite well without a single pin. That surprised me, but there it is.

Apart from the fiendish cold, the reason I don’t go out much is fear. Call me namby-pamby, but I am terrified of the twin perils of snow-blindness and piblokto. The wolves and the rampaging wild boars I think I could handle, using a combination of mesmerism and gibberish, but neither of those is of much use where the ruination of one’s eyes and one’s mind is at stake. I have noticed that the wolf-hunters all seem to be equipped with very natty sunglasses, which presumably protect them against snow-blindness. Whether they have something similar to guard their brains I do not know. They are not a talkative lot. Oh, they will gobble down the soup you proffer them, but that’s as far as it goes.

On one of the radio stations I am still able to pick up, I heard the other day that the Ice Age might be coming to an end. Some pundit in the studio was wittering on about all the snow melting, across the tarputa, for as far as the eye could see, revealing a buried landscape, a vista of salt flats. It sounded to me as if his vision was little different from the snowbound land of the Ice Age. But I suppose if it does get warmer I might go out from time to time, though I am not sure to what purpose. I don’t put salt in my soup, never have.

On Frogmen And Toadies

We know, or we ought to know, that a frogman is not a hideous abomination of nature, a fusing in one being of frog and man, such as might come crawling out of the sea on to the shore at Innsmouth in a tale by H. P. Lovecraft. If that is what we were told, we were misled, possibly to frighten us. We have absolutely no need to be frightened of frogmen, unless, in the case of naval commando frogmen, we are the enemy, or, in the case of police frogmen, we are malefactors, ones who have perhaps tried to conceal the body of a murder victim in a deep lake. But generally speaking frogmen are to be admired and applauded. Even if we are standing on the shore at Innsmouth, and we see a frogman emerge from the sea, we should not shudder but clap. He will almost certainly have been engaged in some act of subaquatic heroism, such as affixing explosives to the underside of an enemy submarine. If we are lucky, even as we are clapping, we might see a plume of water rising in a tremendous burst from the sea, and hear a muffled bang. That will be the submarine exploding, a decisive blow against the enemy which brings us ever closer to the day of victory.

The frogman is not to be confused with the toadman. Just as some people have difficulty distinguishing a frog from a toad, so we will from time to time come across a person who thinks the frogman and the toadman are synonymous. Nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed they are so different that the only reasonable explanation for such confusion is that we have been taken in by enemy propaganda. It is quite possible that the enemy submarine so heroically blown to smithereens by the frogman was carrying a cargo of teeming thousands of leaflets designed to muddle our heads with lies about frogmen and toadmen, and even about frogs and toads, so we have all the more reason to applaud the frogman who comes padding on to the shore at Innsmouth under cover of darkness, his heroic deed done.

Whereas the frogman is brave and admirable, the toadman is the opposite. So loathsome is the toadman that few of us can bear to utter his name, which is why it is usually shortened to ‘toady’. A toady is a servile parasite, a sycophant, a fawning flatterer. Standing on the shore at Innsmouth, clapping our hands at the frogman as he emerges from the sea upon completion of his heroic action against the enemy submarine, we run the risk of being taken for a toady. For this reason, we should not applaud him too long, nor overegg the pudding of our approbation. A brief flurry of clapping and a manly slap on his shoulder will suffice. Then we should turn away and return to the seafront hotel where we have taken a room, leaving the frogman to report to his superiors at a different seafront hotel which has been commandeered as operational headquarters for the duration of the war.

But not all admirers of our subaquatic commandos show such reserve and restraint. It is a sad fact that the very heroism displayed by frogmen attracts toadies. In Innsmouth alone, one study has shown that for every frogman billeted in the one seafront hotel, there is a corresponding toady renting a room in the other seafront hotel. These toadies are not only servile parasites, sycophants, and fawning flatterers, they are pestiferous and constitute a security risk. By tumbling out of their hotel every morning and thronging around the other hotel, the operational headquarters, which are meant to be top secret, with their cameras and autograph books and bouquets of posies, they draw undue and unwelcome attention to the frogmen. And heroic as they clearly are, it has to be admitted that some frogmen find themselves captivated by the attention of even the most loathsome and slimy of the toadies. They are happy to accept the bouquets, to scribble their autographs, and to pose for pictures, arms slung around the shoulders of the toadies, as if fast friends. Their superiors, hunched over maps in the converted ballroom of the seafront hotel, are too busy planning the next thrust against the enemy to distract themselves by bawling out the frogmen and urging them to shun the toadies. That is why we have taken a room in the other hotel, the one infested with toadies.

We had chanced upon an article in the Innsmouth Bugle in which one particularly heroic frogman, impervious to the fawning of the toadies, complained in the bitterest tones about their attentions. “We frogmen need no toadies,” he was reported as saying, “And they distract us from the important business of preparing ourselves, mind and body, fins and flippers, for the important work of affixing explosives to the underside of enemy submarines under cover of darkness.” Patriotic to a fault, we could not read those words without hurling our teacup across the room, smashing it upon the wainscot, and rushing at once out of the door to the railway station to catch the special train to Innsmouth, where, having identified which seafront hotel was which, we booked in to the one riddled with toadies.

Tonight, after our brief applause and manly slap on the shoulder of the frogman emerging from the sea, we return to the hotel. Clad all in black, and in stockinged feet, we pad from room to room, and in each room, silent and deadly, we smother the toadies with their pillows, one by one. This is our contribution to the war effort. And one by one, at dead of night, we drag the still-warm corpse of each toady to the charabanc we have hired and parked outside, and when all are aboard we put on our chauffeur’s cap and drive away from Innsmouth, through the dark, through the countryside, to a deep deep lake. We drag the bodies of the toadies one by one from the charabanc and weigh them down with stones and pebbles, and we toss them into the lake. And they sink, and are hidden, and will no longer fawn over our heroic frogmen.

Years pass before a new generation of frogmen, some the sons and nephews of the wartime frogmen, working, now in peacetime, for the police, dredge the lake. They are responding to persistent rumours put about by communists. The rumours, of course, are true, and one by one the police frogmen, no less heroic than their commando forebears, bring to the surface the skeletons of toady after toady. We read about their exploits, and see the photographs, in the Innsmouth Bugle, but we are far away from Innsmouth, and aged, and doddery, and nobody would ever guess what we did, in the war, in our own small way, to win victory.

St Elmo’s Fire

In the midst of a storm, [Antonio Pigafetta] writes,

“The body of St Anselm appeared to us . . . in the form of a fire lighted at the summit of the mainmast, and remained there near two hours and a half, which comforted us greatly, for we were in tears only expecting the hour of our perishing. And when that holy light was going away from us, it gave out such brilliance in our eyes that for nearly a quarter of an hour we were like people blinded and calling for mercy . . . It is to be noted that whenever that light which represents St Anselm shows itself and descends on a vessel in a storm at sea, that vessel is never lost. Immediately this light departed, the sea grew calmer, and then we saw various kinds of birds among which were some that had no fundament.”

This is not a hallucination – he is describing the electrical phenomenon known as St Elmo’s Fire – but the language tends towards the visionary, and ends with this decidedly odd seabird that lacks an anus.

Charles Nicholl, in “Conversing With Giants”, collected in Traces Remain : Essays And Explorations (2011), quoting Antonio Pigafetta, who met giants in Patagonia. Pigafetta was a supernumerary passenger on Magellan’s voyage of circumnavigation (1519-1522), one of the few who made it back to Seville.