I have not read Geoff Dyer’s new book Zona : A Book About A Film About A Journey To A Room. As the title indicates, it is devoted to a film, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) and to Dyer’s obsession with it. I vaguely recall seeing Stalker, probably around the time of its release, and have not seen it since. Clearly it did not make a great impression on me, unlike the same director’s Andrei Rublev (1966), which I saw in the mid-seventies and from which I can still remember certain scenes. Reading a couple of reviews of Dyer’s book led me to wondering which film I would choose to write an obsessional book about.

It then struck me that, much as I might be given to enthusiastic ravings about, say, Celine And Julie Go Boating (Jacques Rivette, 1974) or The Falls (Peter Greenaway, 1980), or Random Harvest (Mervyn LeRoy, 1942), or Even Dwarfs Started Small (Werner Herzog, 1970), or pretty much anything directed by Guy Maddin, it is unlikely I will ever sit down and concentrate and write about them at length.

Dyer’s Zona is, apparently, “one long movie summary, a shot-by-shot rewrite” of Stalker, which I assume indicates that he gives us a detailed account of the film and wanders off into discursive byways. (At one point he provides us with the useful information that, after the completion of Sympathy For The Devil / One Plus One (1968), Mick Jagger said of Jean Luc Godard “He’s such a fucking twat”.)

Taking a similar approach, might it not be interesting to consider not just one of my favourite films but, say, three of them, and construct a narrative that intermingled them, had elements from each colliding, happily or otherwise, stirred them together in a pot and made something new and strange? I think this is what young persons call a “mash up”. What would happen were I to sprinkle together, in chronological order, Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1945), Noroît (Jacques Rivette, 1976), and Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988)?

Certain choices, or strategies, seem compellingly obvious. Hans Gruber and his criminal gang could invade and hold hostage the occupants, not of the Nakatomi building but of the coastal castle which is the setting for Noroît. Ah, but the castle is home to a pirate gang rather than a law-abiding Japanese corporation. So Giulia, the pirate leader, could be replaced by Laura Jesson’s well-meaning but exasperating friend Dolly Messiter. Ruthless German criminals pitted against Francophone female pirates, both perhaps to be outwitted by New York cop John McClane, who is attempting to rescue Laura, aided by Erika and Morag, the avengers. Dr Alec Harvey can sit in a police car with Sergeant Al Powell, parked close to the castle, perhaps in the lee of the pollarded willows by the canal just before the level crossing.

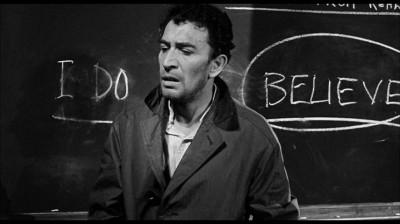

Noroît is partly based on The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606), long attributed to Cyril Tourneur but now thought to be the work of Thomas Middleton. These echoes of dark brooding Jacobean tragedy should serve to remind us that in Brief Encounter, the part of Dr Stephen Lynn, Alec’s colleague from whom he borrows the flat for his unseemly and sordid – and ultimately abortive – assignation with Laura, was played by an uncredited Valentine Dyall (1908-1985), an actor whose sepulchral tones made him famous as the Man In Black, host of the long-running BBC radio series Appointment With Fear. I do not know if Valentine Dyall ever acted in any Jacobean tragedies, but if he did not, he should have. He did do some Shakespeare.

We would have to find a role for Dr Stephen Lynn, perhaps applying his professional medical knowledge in the closing scenes of Noroît, where at a torchlit nocturnal masked ball Morag and Erika and Giulia, oops, I forgot, Dolly Messiter, get a bit carried away with the stabbings. I suppose John McClane should be wandering about in the dark somewhere, too, bloodied and in his vest.

I realise that I have not yet managed to insert any steam trains, nor Albert Godby nor Myrtle Bagot from the Milford Junction tea room, nor Holly Gennaro-McClane, nor the pirate castle musicians. But fear not, space will be found in my narrative for all of them.

I am in something of a quandary about the title, for though one can cobble together various combinations of, here given in alphabetical order, Brief and Die and Encounter and Hard and Noroît, no one admixture springs out as obviously preferable. For the time being, while I continue to worry away at it, like a dog with a bone, I shall refer to it as My Own Zona, echoing Geoff Dyer.

Cast, in order of appearance:

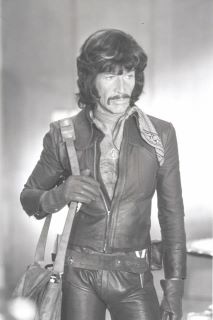

Hans Gruber – Alan Rickman (1946- )

Giulia – Bernadette Lafont (1938- )

Laura Jesson – Celia Johnson (1908-1982)

Dolly Messiter – Everley Gregg (1903-1959)

John McClane – Bruce Willis (1955- )

Erika – Kika Markham (1940- )

Morag – Geraldine Chaplin (1944- )

Dr Alec Harvey – Trevor Howard (1913-1988)

Sergeant Al Powell – Reginald VelJohnson (1952- )

Dr Stephen Lynn – Valentine Dyall (1908-1985)

Albert Godby – Stanley Holloway (1890-1982)

Myrtle Bagot – Joyce Carey (1898-1993)

Holly Gennaro McClane – Bonnie Bedelia (1948- )

Castle Musicians – Jean Cohen-Solal, Robert Cohen-Solal, Daniel Ponsard (dates unknown)

And here is the seaside castle where the action takes place: