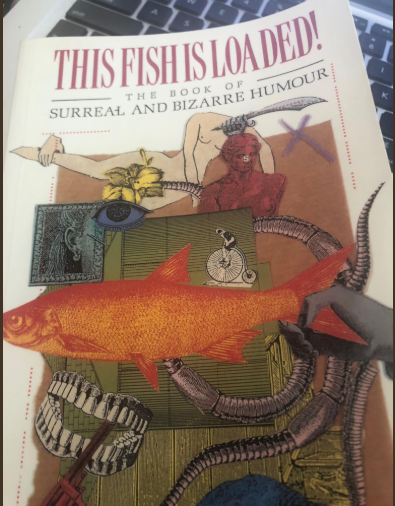

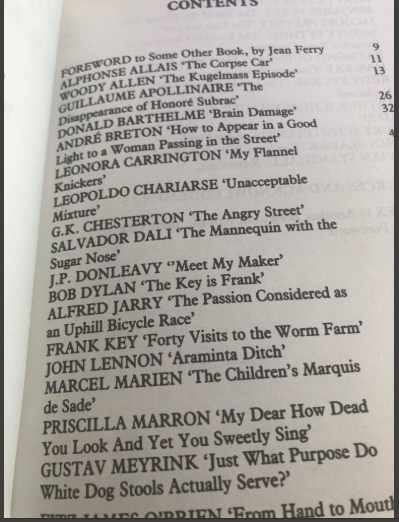

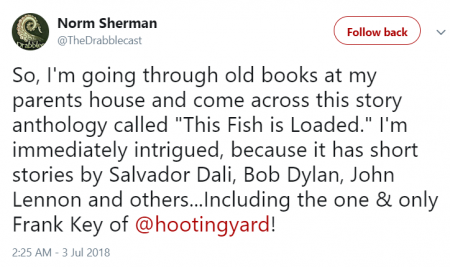

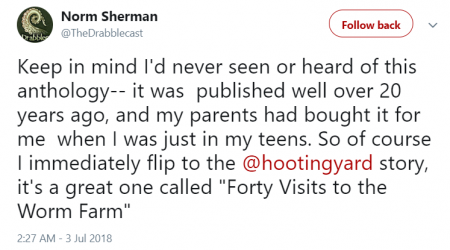

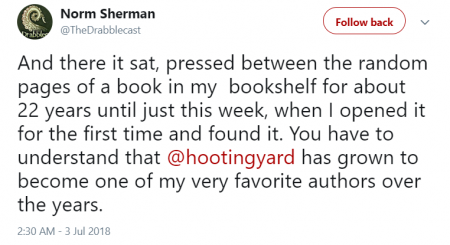

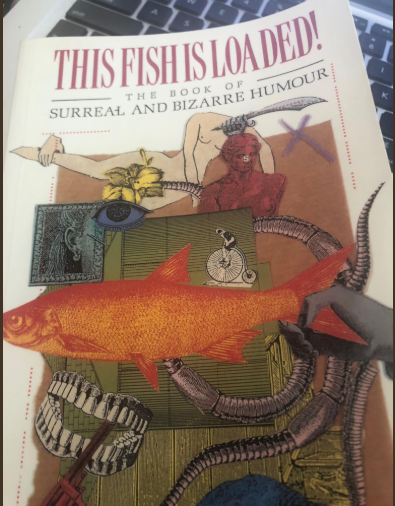

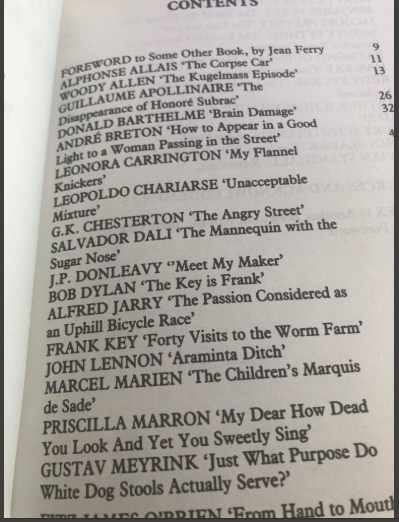

The great Norm Sherman of the (recently revived) Drabblecast reports on an important discovery …

There seem to be plenty of copies available on eBay …

The great Norm Sherman of the (recently revived) Drabblecast reports on an important discovery …

There seem to be plenty of copies available on eBay …

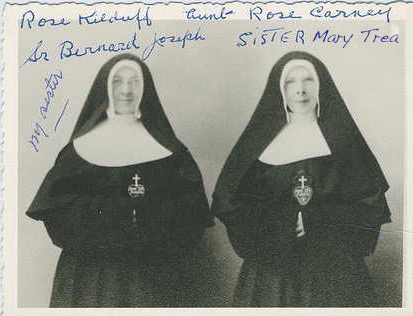

The row between Twittery Corbynistas and the BBC over Jeremy Corbyn’s hat – a row some have dubbed Hatgate – reminded me that during the late 1960s, at the height of the Cold War, my father sported a Russian-style winter hat. This led some neighbours on our council estate to surmise that my Pa was a Soviet spy. The fact that he regularly popped in to the newsagent’s to pick up a copy of the Morning Star probably added to their suspicions. Unfortunately I don’t have a photograph, doctored or otherwise, of my father in his Communist headgear.

One of the amusing things about all the nitwit fans losing their marbles over supposed BBC perfidy is that there must be thousands of photographs of Corbyn wearing self-styled “revolutionary” attire. Remember that the dear leader’s politics are still those of an earnest teenager circa 1968. Before becoming Labour leader, he was regularly pictured wearing Leninist workers’ caps or one of those scarves the Palestinian death cult maniacs are so fond of.

OK, now I’m off to the political re-education camp to learn the errors of my ways.

Here is an old favourite, written over thirty years ago. Two words have been changed from the original version. I have no idea what it means, but it might be diverting to subject it to piercing critical analysis. Does anybody want to have a go?

Hats are off in Docking; caps are being doffed. The council’s got a town plan. The maths are on a chart. Pips have been spat out and drudgery is bye-byed. Chocolate puddings seem to be in everybody’s pantry. And here comes Pebblehead père. He caught a shark in waters. His sou’wester’s been askew since 1954-ish. Bubbles surge from froth. The chemist’s shop is shut. There’s pills & pills & pills that no Docking man could swallow. Suffering aborted. The council in a caucus. The shaven heads of heads of state are battering the doors down. The city gates, the turrets, the alleys, roads & mews: Docking has its ears all go for red alert decisions. Language has been no-no’d, the bamboo men are wailing, the breakage rate is scheduled: the system has been broken. Crayons pink & stacked, the burnt sienna packaged. Vandals clash at nightfall, but Docking has its crackers. Plastic wrapped in plastic. The Docking coffers emptied. Idiot brawl saloon bar, a gorgeous snag-tooth babble. Prepared to dance a hoo-cha, not a tear or boo-hoo. Thousands of museums stacked with golden maps. Misshapen trunk road closures. Big stone reconstructions. Docking’s cottoned on: it’s a town about a tower. The frame is out of kilter, the coughing’s filling coffins. Oh, but I want to go back to that Docking, Docking hack.

Further to all the guff I mentioned about Hooting Yard housekeeping last week, there was a little flurry of concern regarding the vanished ResonanceFM podcasts. As a result, I have embarked upon a foolhardy yet I hope rewarding project to upload hundreds of past episodes of Hooting Yard On The Air to YouTube.

Et voila! Here is the first fruit of my tireless efforts – the very first show, broadcast all those years ago on 14 April 2004. Malachy O’Neill was the sound engineer.

I am hoping that further episodes will appear on YouTube on a regular basis, until the whole damned lot are there. This will take time. I am open to offers of help, should there be any devotees out there thrumming their fingers idly on the windowsill and staring into space, in need of some useful unpaid occupation.

ADDENDUM : Episode Two (21 April 2004) also added.

ADDED ADDENDUM : A link has been added to the sidebar to take you straight to the Hooting Yard home on YouTube. When you get there, press “Play All”, sit back, sluice out yer lug’oles, & listen until the cows etrcetera etcetera …

On 28 December 1973, I attended my first gig. I had been taken to concerts before, notably (and inexplicably) by my father to the Albert Hall to see the absurd gravel-throated troubadour Rod McKuen, but this winter’s night was my first outing, unaccompanied by an adult, to the world of rock. My friend Paul Pearce and I took the Central Line into London from our homes in the blighted wastelands of suburban Essex, and fetched up at the Lyceum, just off the Strand. We had come to see … Gong (or The Gong, as Bernard Levin would have it).

Now, bear in mind that I was a wet-behind-the-ears young teenperson. Molesworth would have called me uterly wet and a weed, and he would have been right. Somehow, in the preceding months, I had managed to convince myself that a bunch of drug-addled hippies caterwauling about gnomes and flying teapots represented a world I was avid to be part of.

Many of my schoolfriends were in thrall to glam rock, but I pooh-poohed Marc Bolan and David Bowie and their ilk as hideously commercial. I veered towards what I thought of as the progressive and the underground, and Gong fitted the bill. So there were Paul Pearce and I, wide-eyed and innocent, surrounded by long hair and beards and kaftans and foul-smelling Afghan coats, while on stage Daevid Allen and his chums caterwauled and parped and made the kind of din I told myself I adored.

Being wet and weedy, Paul and I of course had to ensure we did not miss the last tube train home, so we left the gig early. My memory is dim, but I suspect I was elated. I had seen my future, or so I thought. I would live in a filthy commune and take lots of drugs and reject straight society and possibly even strum a guitar.

It did not quite work out like that, though the dream lingered for a couple more years. I went to lots more gigs, and saw Soft Machine and Stackridge and Henry Cow and Wally and Kevin Coyne and Jethro Tull and Hatfield & The North and many others. But I never saw Gong again.

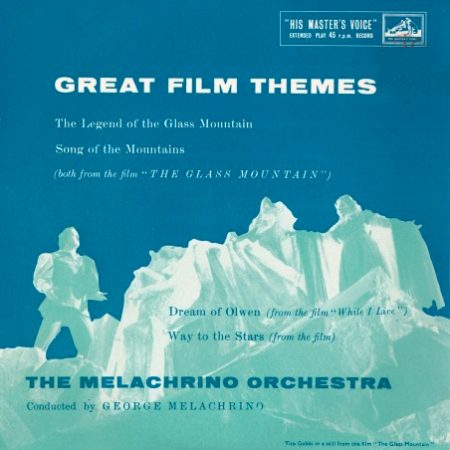

This 7” EP was in my parents’ record collection. As a tiny tot, I found the image of the two lovers, turned to glass, frozen and immobile atop a mountain, absolutely haunting. And that blue!

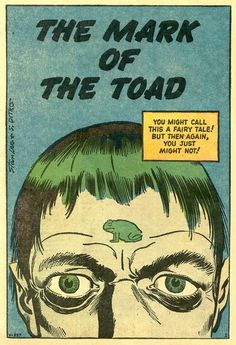

This week is meant to be Dobson Week at Hooting Yard (atoll, pickle, mosh pit), but we must interrupt with important news o’ toads. Devoted readers will recall The Book Of Gnats (collected in the slim anthology We Were Puny, They Were Vapid – buy it now if you have not already done so). In part one, we read:

And then my eyes saw, standing fiery on a wooden plinth ringed by scum-pools, the obscene figure of Winckelmann. In his left hand he brandished aloft a scrap of burning linoleum. His right hand was made into a fist. As, dribbling, I watched, the fist was slowly opened to reveal a….. I cannot say. I do not know. For just at the moment my peering, watery eyes would have seen that… that thing, I was startled by a toad, which leapt up at my face, and thwacked me on the forehead, leaving an imprint which remains there to this day, like a brand.

The narrator of part one then turns up in part two as The Man With The Mark Of The Toad! (He invariably attracts an exclamation mark.)

Now, years later, far far away and banished to a pompous land, Mr Mike Jennings has unearthed this piece of comic book art by the creator of Spiderman, one Steve Ditko. An eerie premonition …

Well, there you go : that was Obsequies For Lars Talc, Struck By Lightning. It was a curious experience retyping something I’d written almost a quarter of a century ago. Chief among my torments was the desire to tweak, rephrase, rewrite. But I knew that if I started along that path, I’d end up with a considerably different text. On a very few occasions, I could not resist. (For example, a misuse of the word fulsome. I know this is now routinely misused, to the point where its proper meaning is likely to be lost, but damn me if I’m going to help it on its way.) When, like Lars Talc, I am long dead, scholars of the future will no doubt pore over this version and the original, triumphantly spotting the minor changes.

That original was published in an edition of twenty-five copies in 1994. This new one is available free of charge to billions of readers across the globe. That is the cataclysmic change that occurred between the time I finished Obsequies, and descended into my Wilderness Years, and when I emerged from them, in the new century, to find that Het Internet had happened, and this website came mewling into existence. It is instructive that the actual number of my readers probably hasn’t increased significantly.

Another change, implicit in the text, and one I could not help but notice, is that my twentieth-century characters like to glug booze. (Even more so in the other novella written as the demons of debauch gripped me, later published as Unspeakable Desolation Pouring Down From The Stars.) There is not a drop of aerated lettucewater to be found!

Lars Talc and Minnie seem to be ur-versions of Dobson and Marigold Chew. However, the character I most warmed to, as I retyped, was the mysterious Bruno. It is never made clear precisely who he is, nor the nature of his relationship to Talc and Minnie. I suspect he may be worthy of a spin-off series of tales.

Certain passages were lifted without acknowledgement from The Little Cyclopaedia Of Common Things by Rev. Sir George W. Cox, Bart., M.A. (1894), the Journals of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and (if memory serves) Death, Ritual, and Bereavement, edited by Ralph Houlbrooke (1989).

I may republish Obsequies in a near-facsimile edition via Lulu. In the meantime, you may feel compelled to recognise my titanic retyping efforts by plopping some moolah into the Donation box.

Children, if you have read this far, take heed. Lars Talc could not have known that he carried in his pocket, embedded in his prize horn, a lightning conductor of superb efficiency. But you will be on your guard.

You will not forget to ask papa to place an egg laid on Ascension Day, and a houseleek plant, in the rafters of your dwelling.

You will not fret and dally at the onset of a thunderstorm, neglecting to throw open all the doors and windows, to turn pictures to face the wall, and to cover your mirrors with heavy blankets.

You will not forget to wear a wreath of laurel, and a necklace of coral.

You will never put your shiny new boots upon the table.

You will not attempt to count the twinkling stars, nor point with your finger towards that part of the heavens whence lightning is expected.

You will not forget to gather bundles of hazel and willow twigs and stand them in pots of water.

If you pick a poppy, you will not let a petal fall from it on to your hand.

When mama tells you to gather up the knives and forks and spoons and scissors and scythes and tweezers and pincers and pins and needles and all other implements of steel, and put them away in the cupboard, you will not disobey her.

You will not hang back when your pals go scampering to the churches to set tolling great clamours of bells.

You will not stand near towering pines, nor up to your ankles in a basin of water, nor by any leaden spout, iron gate, railings, bandstand, palisade, or spigot in times of lightning.

Will you?

THE END

Minnie had chosen well in Potcap. Everything went according to plan. Aloysius Batlip supplied a tiny cadet named Vig, who scurried among the mourners with the funeral schedule, ticking off the names, logging the times, counting the animals, and ensuring that Minnie’s wishes were met to the letter.

As she had expected, the Reverend Chew’s sermon was the centrepiece of the funeral. His ovation lasted for thirteen and three quarter minutes. He stood poised in the pulpit of the Gravelflap auditorium, and as the rustle of applause finally died, he peered over his sinister spectacles at the twenty-six mourners, cleared his throat, and began to speak.

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered here in memory of Lars Talc. How can I, in my treacly voice, do justice to the memory of such a man? I could tell you the story of his life, but he was ninety-four, and it would take days, even weeks, to recount even the merest essentials. Were I to pick only selected, epiphanic incidents – the reinvention of bleach, the ascent of the mountain at Hoon, a fist-fight with a bus conductor, the creation of the postage stamp zoo – I would be imposing on the memory of his life a partial, fragmentary view which would be irreconcilable with the mighty genius he was. It will not do. What, then? It has been suggested to me that I could sing all one hundred and fourteen works from his magisterial songbook. But how could my puny, fluting tones equal the bliss of hearing Talc perform them himself? And, thanks to Minnie, we have the tape recordings. No, a recital by me would be quite, quite unendurable. How to get the measure of the man? Take you on a tour through his wardrobe? Read snatches from his books? Tell childhood anecdotes? Bluster? Gabble? Gibber? Hold up his example as a paragon of what it means to be a Finn? To be human? None of these will suffice.

“So let me say this. He owed me a great deal of money. He was covered in dust. He couldn’t tell the difference between a heron & a moorhen. He never learned the rules of ice hockey. He was often plagued by mysterious boils. He had a scar on his left shin. He confused the different metallic elements. His hair was often unkempt. He set fire to a Bible. His pigs were neglected. Adept at ping pong, he weighted his bat. He once suffered from scrofula. His tent had many holes. He never wore a hat. His gas bills drove him crackers. He spoke umpteen languages. His mother told me he was terrified of swans. Geology was beyond him. He hankered for doilies. He counted toads. His bath was made of tin. His first marriage was disastrous. He could not ride a bicycle. He spat out mayonnaise. He avoided paying for hotel rooms by clambering down fire escapes. Once he built his own bridge. He burned himself in effigy. He loved to eat turnips. He often drooled. His thumbs were deformed. Rust and rime engaged his attention. He was much travelled. He designed his own pen-nibs. He kept a photograph of Ricardo Montalban in his bureau. His eyesight was atrocious. Candles have been lit for him. His credentials were spotless. He punched a fishmonger. He gutted huts. Linctus slithered down his throat. He owned dozens of fret-saws. He thought the moon was his lover. In Didcot he wept. He fed flamingos with cream crackers. In certain circles his name was mud. He kept his gutta-percha in a gunny sack. The sight of geese made him anxious. He smoked cheroots. He re-counted toads. He held aloft a blubber-lantern on the banks of a duckpond. His saliva was bitter. Taxes were levied upon him. He had a zest for crumpled things. In parks he pondered. He bit his fingernails. He chewed spinach. At a pinch he would talk for hours on the subject of straw. He wiped his bottom with leaves. He wrote a book about gnats. He mumbled through a tube. Things dangled from the ceiling of his boudoir. He lost on the horses. He wrapped a tortoise in blankets. As a youth he survived on crusts. His father painted difficult maps. Often he behaved like a madman. Twigs and branches fell unremarked in his garden. Rowing held no allure for him. He dabbed at his brow with ointments. He was fond of cormorants. He coaxed mice from their nooks. He was knocked down by a runaway bus. Clods of earth surrounded him. He could be petulant. He strained things in a muslin net. He pulverised a diving board with his bare hands. Morse code baffled him. He nearly became a marine. He moved his arms towards the lake. Under a cow tower he looked at planks. He overcame his stutter. His sheep had worms. He crossed himself. He played at bagatelle. He spied a crocus. He fainted. He snored. He panted. He sprayed. His stomach. His hearing aid. His cuffs. His gristle. His sponge. His batteries. His hardship. His chutney. His paths. His windows. His calcium. His rudders. His vinegar. His seeds. His nettles. His sores. His stool. His plastic. His incandescence. Autumn. Shipwreck. Curtains. Exile. Frost. Balconies. Pandaemonium. Hedgerows. Banisters. Carpets. Hinges. Remembrance. Hair. Custard. Dribble. Fanfares. Dampness. Bauxite. Trousers. Canals. Boskage. Lasciviousness. Tunics. Spigots. Iron. Lint. Cranks. Floozies. Doppelgangers. Tin. Bales. Agony. Loss. Lust. Love. Crack. Bang. Crunlop. Lars Talc is dead.”

Minnie had decided that all twenty-six mourners would attend the funeral bedecked in costumes made entirely of feathers. All feathers are made alike in their general form, although they differ greatly in size, strength, and colour.

Each one has a quill, or barrel, a shaft, and a vane, beard, or web. The quill is a hollow horny tube, made of hardened albumen. It has an opening at the bottom, and one where it joins the shaft, and has inside a thin dry core. The shaft is smaller and longer than the quill, and is nearly flat on each of its four sides. It is made of a white spongy substance called the pith, covered with a thin horny sheath. The vane or beard, which is in two parts, one on each side of the shaft, is formed of many small flat plates or scales, which grow out of the sides of the shaft, and lie with their flat sides close to each other. These sides have along their upper edges little hooks, or barbules, by means of which they hold fast to each other, so that the surface of the beard is close and smooth and does not open when the bird is flying.

In some birds, like the ostrich, these barbules do not hook very tightly together, and this makes their feathers more soft and plumy than those of other birds. At the bottom of the beard, next to the quill, there is usually a small feathery tuft called the plumule, or accessory plume. Besides the feathers, many birds have next to the skin a soft fleecy covering called down, which is made up of very small feathers.

Feathers grow very fast, and almost all birds change them every year. Feathers vary in size and in form in different parts of the body, and have received different names from those who write about birds. Most birds have a small gland, or kind of bag, at the base of the tail, from which they squeeze out oil with their bill, and spread it over their feathers. This is partly the reason why birds’ feathers shed water.

Of ornamental feathers, those of the ostrich are most prized, especially the large white plumes from the back and tail of the male bird. But many other birds, such as the peacock, swan, turkey, pheasant, cock, heron, egret, osprey, eagle, ibis, rhea, emu, adjutant, grebe, marabout, stork, and widgeon yield feathers which are used in ornament.

In preparing feathers for use, they are tied up in bundles and washed in warm soap and water to free them from grease. The soap is then rinsed out in clean hot water, and they are then plunged into boiling water into which a few drops of saffron distillate have been mixed. After further rinsing, they are drawn quickly through cold water with a mixture of a little ground agaric, and are then steamed over sulphur fumes and dried. The shafts are scraped to make them limber, and the filaments or feathery parts are patted gently with special light-weight hammers.

Minnie had wheelbarrow-loads of feathers delivered to her apartment by a team of feather-gatherers drawn from different bird-houses scattered throughout the town. Working like a drudge, she made all the costumes herself, scarcely pausing to sleep. As each costume was finished, Bruno packed it into a large cardboard packet and delivered it personally to the recipient. In turn, at intervals of a few hours, Aminadab, Bewg, Chodd, Darningneedle, Eck, Freakpit, Gum, Dr Hoist and the others answered their doors to find the terrifyingly pale figure of Bruno standing before them, the packet in one hand and an invitation to the funeral in the other.

Minnie had commissioned a rancorous Stalinist hobbledehoy to illuminate the invitations. Josef Megrimovitch Bong lived in a pigeon-loft above one of the finest houses in the town, and seemed to subsist on a diet of rusks, mugwort, and tap water. His creaking, spavined frame, clad in a muddy black cape, was often seen stalking aimlessly along the boulevards, spitting at children and stamping on puppies. Minnie was his only friend – even Talc had loathed him – and spying him on her way back from the screeching of the will, she dropped some rusted coins into his hand and bid him draw up the invitations. For though he was almost universally hated, every Finn who knew him had to admit that Bong’s calligraphy was of stupendous beauty.

“Know ye,” read the invitation, “That Professor Lars Talc was struck by lightning on Tuesday last, as he bestrode the Avenue Ack. Aye, weep, for the great Finnish polymath is no more! The huge throbbing brain is stilled! Mourn with every particle of your yet quick being! You are commanded to be present at his Obsequies. At dawn on Sunday we will gather at the gazebo on Pilgarlic Hill. Be there, or abominations will rain down upon you. And wear these feathers, and nought else, for if you do not, you will answer to Bruno, and he is fearsome in his wrath! Attend, or be besmirched!”

None dared disobey the call.

Minnie threw herself into the funeral arrangements with astonishing energy. At ninety-seven, she was three years older than Talc, but the years had not dimmed her eupeptic zest. As executrix of the estate, she accosted Chodd – thinking he was Batlip – within seconds of the will being screeched.

“I will be in charge of the funeral, down to the tiniest detail,” she rapped, “You, Aloysius, will do my bidding. Your first task is to arrange for the Bosnian nerve gas billionaire, Turps Potcap, to be at my apartment at ten o clock tomorrow morning on the dot. Meanwhile, Talc is to be refrigerated at the lowest possible temperature you can manage. Snap to it.”

At ten o clock the next morning, Turps Potcap was ushered in to Minnie’s sitting-room. He was almost as wizened as she, but a quarter of a century younger. Born of Bosnian lumpenproles who died of the groist when he was a mere tot, Potcap was brought up in a frolicsome orphanage run by the famed reformer Hattie Brinks. At fourteen he was already displaying his formidable intellectual gifts, delivering lectures on a variety of abstruse subjects to his dumbstruck peers.

Mistress Brinks enrolled him at the University of Tuzla, where he soon humiliated his teachers by addressing them in fluent Coptic, a language none of them understood. Before his sixteenth birthday, Potcap was appointed Corncrake Professor of Physics at a crumbling but important university in Burma, a post he held until he was forty. By then, however, he had invented a nerve gas of staggering power, which he patented and sold in vast quantities to governments around the world.

The effects of Potcap’s gas, on one exposed to it, are temporary but devastating. The victim invariably runs to the nearest tobacconist, buys a huge quantity of cigarettes, slumps to the ground and sits, babbling, gesticulating, and smoking heavily, like a student. Meanwhile, the tanks, artillery, and special operations militia move in, and by the time the effects of the gas wear off, a couple of days later, the commanding heights of the socio-economic infrastructure are in the hands of the invading forces.

Potcap made an absolute fortune, of course, and retired from academia. He lived simply, spending much of his time engaged in various secretive and pointless research projects, but occasionally hiring himself out as a “special consultant”. He had, for example, designed a new whisk for a utensils conglomerate, written a lengthy report on pigeons’ blood at the behest of the Hooting Yard Foundation, conducted dangerous experiments at an international hot air ballooning conference, and solved the bogus laundry murder case, which had befuddled the minds of the Dutch police for six years. With such a pedigree, he was Minnie’s natural choice to organise Lars Talc’s funeral.

She steered Potcap to an armchair and gave him a mug of soup.

“Thank you for coming at such short notice,” she said, “First of all, I must ask you if you are familiar with Talc and his work?”

“I am not,” replied Potcap.

“Splendid!” shouted Minnie, unnecessarily loudly, “I am so glad. The Finns think they know Talc, you see, they think they understand him. That’s why I have asked you here, because you will approach the task objectively. You will bring no mental baggage in your train.”

“What is this task you speak of?”

“I wish you to organise Talc’s funeral, Mr Potcap,” said Minnie.

The Bosnian billionaire was startled. “O is he dead then?”

“Two days ago he was struck by lightning. Here is a newspaper clipping. You may keep it if you wish.”

Potcap read Battista Ritnob’s brief report, then tucked it carefully into his wallet.

“If I may say so, madam, you have made an excellent choice in selecting me for this task,” he announced. “Although I have never organised a funeral before, I am more than equal to the challenge. Is he to be buried or burned?”

“Buried,” said Minnie.

“Good. Humans are the only creatures who bury their dead. The fact is of fundamental significance. Palaeolithic peoples not only buried their dead, madam, but they provided them with food and other equipment, implying a belief that the dead still needed such things in the grave. Tosh it may be, but significant tosh, highly significant, eh?”

“Talc spurned all religion and other shilly-shallying.”

“As I do myself, madam,” said Potcap, gulping down his soup. “Nevertheless, burial of the dead stems from an instinctive inability or refusal to accept death as the definitive end of life.”

Minnie snorted. “What else can you do with a corpse?” she asked.

“Burn it,” said Potcap, “Or leave it where it is. But let that pass. Talc shall be buried. As he was not a Christian, I suppose you do not wish the funerary ceremonies to be invested with a sombre character, the visible expression of which would be the use of black vestments, and candles of unbleached wax and the solemn tolling of a church bell, the corpse being carried in a doleful cortege of clergy and mourners, with the intoning of psalms and the purificatory use of incense, and, the coffin being deposited in the church, it being covered with a black pall, and the Office of the Dead recited or sung, with the constant rendition of Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him, followed by the recitation of the Requiem Mass, with the sacrifice especially offered for the repose of the soul of the dead, then the absolution of the deceased, the coffin solemnly perfumed with incense and sprinkled with holy water, before being carried to consecrated ground and buried while the officiating priest whines a litany of appropriate prayers?”

Minnie spat.

“I would rather lie on my back at the bottom of a pond than take part in such trumpery! No, Mr Potcap, I have very clear ideas about Talc’s funeral. You will need to take notes. While I fetch more soup, you had better sharpen your pencil. Here is a wastepaper basket for the shavings.”

Turps Potcap sharpened his pencil. Minnie brought two mugs of boiling soup.

“The funeral will take place in three days’ time,” she said, “You will have lots of work to do. Now listen carefully. Including you and me, there will be twenty-six mourners, selected on an alphabetic basis. I will give you the names later. If anyone else tries to attend, Bruno will frighten them away. He has a talent for scarifying.

“We will gather at dawn in the gazebo on Pilgarlic Hill, to which Batlip will have delivered Talc in his coffin the night before. There will be a funeral breakfast, consisting of porridge, ships’ biscuits, and whey. We will then form a cortege, each mourner travelling separately in a different form of transport. Batlip’s hearse will be at the front, of course, and immediately behind it me, borne on a palanquin. The other carriages will be a landau, a motorbike, a rickshaw, a charabanc, a covered wagon, a brancard, a tumbrel, an ekka, a scooter, a tilbury, a van, an ambulance, a coach-and-four, a mail-phaeton, a jalopy, a huskie-drawn sled, a bicycle, a hard-top, a wheelchair, a truck, a go-kart, a diligence, a brake, a clunker, and a gig. I have you down for the tumbrel, Mr Potcap, I trust that will be satisfactory?”

“Of course, madam,” said the billionaire, writing frantically.

“Good. We will proceed at a stately pace, with much wailing and gnashing of teeth. Our route will take us past the Cow & Pins, Talc’s favourite drinking-hole. We will all disembark, enter the tavern, and drink heavily. You will have to ensure that the landlord is apprised of our visit, and has in stock many barrels of a special funereal brew. We will not leave until every last drop of it is drunk. Communal ablutions will then take place in the lavatories, after which the cortege will make its way to the Gravelflap Building in the town square.

“The coffin will be carried in on a bier. We mourners will remain outside, where we will eat hockey cake, count noses, drape a toad in ermine, and break into bits a mustard canister. That done, we will enter the building and take our seats. Dr Hoist will then sing song number one hundred and four from Talc’s songbook. It is a dirge of inordinate length, entitled The Grist, The Sack, The Perfume Of Lack. We shall all join in for the chorus. While Hoist moans, Finnish Airline Belles will distribute sprigs of watercress soaked in vinegar, which the mourners will entangle in their hair. Have you got all this written down? Good. We will then applaud immoderately as the Reverend Chew appears in the pulpit.”

“Madam?”

“What?”

“A reverend? I thought you said Talc abhorred religion?”

“He did. But the Reverend Chew is an old friend. His mother and Talc’s mother killed horses together when they were children. He and Talc spent many happy hours side by side, laying plans for a fundamental reform of Finnish cartography. Their innovative map-reading techniques were revolutionary, and even today have not won popular acceptance. It is quite impossible to imagine Talc’s funeral without the Reverend Chew taking part in the obsequies.

“When, after about ten minutes, the mourners have stopped cheering, Chew will deliver his sermon. If I know Chew, it will be a thing of magnificence. There will then be a little concert. I have arranged for a small ensemble of bassoon, sackbut, and twin accordions to play some dreadfully lugubrious pieces. I will then take centre stage and pound my madge upon an anvil, the very picture of hysterical bereavement. Ensure, Mr Potcap, that quick sketches of me are executed at this point. You will find plenty of able scribblers in the directory.

“You will then unleash into the building a sleuth of bears, a chattering of choughs, a sedge of herons, a drift of swine, a congregation of plovers, a cete of badgers, and a husk of hares. Talc was fond of animals. Do not forget to contact the zoo, which must provide not only the beasts but their keepers. Their frolicking done, the animals will be mesmerised by the quack Pillchain, and carted off to the place of interment, whither we too will follow, after lunching on fudge and toffee in the Gravelflap cafeteria.

“When we arrive at the cemetery, I want each mourner to be given an urn to blub into. Batlip and his henchman will varnish the coffin with a stinking substance, and it will be lowered into an enormous pit. We shall stand in a circle around it, sobbing, bereft, but dignified. The animals will be loosed among the tombstones. A troupe of minstrels will prance and caterwaul. Milk, feathers, sand, and fragments from the skull of an osprey will be tossed into the pit. The Reverend Chew will jabber. The sky will darken. We will shuffle away, each lost in our thoughts, going our separate ways, and never gather together again. There. That will be the funeral of Lars Talc.”

“On the day after my death, the exercise book in which I have written my Last Will And Testament will be taken to a desolate spinney. There, its contents will be shrieked by my embalmer, whomsoever that may be. Those gathered to hear it will accompany the embalmer’s shrieks by plucking on primitive wooden stringed instruments. All those present will wear cotton hoods, and go barefoot. This I command.”

Lars Talc had written these words some twenty years before, and published them in a small compendium of his scribblings entitled Shuddering & Brilliantine. Minnie underlined the paragraph and handed a dog-eared copy of the book to Batlip, who read the words with dismay. He was a fiercely shy man, and the prospect unnerved him. With Talc in his coffin, and as he and Chodd rinsed off the embalming equipment and rubbed their hands with Finnish swarfega, he confessed his terrors to his helpmeet.

“I cannot do it, Chodd. I am a deeply religious man, and I have no wish to ride roughshod over the sincere wishes of the deceased, especially so eminent a Finn as Professor Talc. But look, already I am incontinent with fear.”

Chodd dabbed at Batlip’s trousers with a cloth.

“Thank you, Chodd. Oh, how I shiver with apprehension at the thought of public speaking. Two years ago, when I was awarded the All Finland Embalming Medal, I was forced to mount the dais to make an acceptance speech. Sepulchral noteworthies from throughout the land were gathered before me, sitting on benches, agog to hear my every word. The president of the Institute looped the medal around my neck, and they all cheered, applauded, and threw their funeral hats into the air. I was led to a microphone like a villain to the firing squad. Do not chuckle, I am serious. My mouth opened and closed repeatedly, without a word issuing forth. Sweat glistened from every pore. I shat in my pantaloons, and then I swooned.”

Chodd gawped.

“You see,” continued Batlip, “I simply cannot do it. I would disgrace the memory of a towering Finn. I would sully his name. There is only one answer. You will have to play my part. You will be the embalmer. After all, you have given me sterling assistance on this sad day. I ask this favour of you out of proper respect for the departed.”

So it was that at noon on the following day, Chodd, sporting a false moustache and smelling of fish, arrived in the desolate spinney with Talc’s exercise book stuffed into his pocket.

There were twenty-six souls gathered to hear Talc’s last words: Minnie, of course; the ten surviving members of the scientifico-medical club, with Bewg in tow; a bone-setter named Carg; Linnet and his wife; Aloysius Batlip, heavily disguised; a trio of mountebanks with whom Talc had had larks; his neighbour Pillchain; a curmudgeonly widow, name unknown, who was passing the spinney and stopped to ponder the scene; poor, fearful Bruno; Slops Curbin, detailed to attend by the Electro-Magnetic Apparatus Museum Committee; Horst Venk, an old, begrimed friend of Talc’s from their student days; the journalist Ritnob; and Ingborg Todge, a blind and foul-mouthed army captain who, he kept telling everybody, had known Talc for years, though he was unknown to all those present, including Minnie, who deliberately crushed his toes under her black boot to stop his incessant babbling.

Chodd distributed the little cotton hoods which he had found next to the exercise book in Talc’s cast iron cabinet and, at full screech, ordered the assembled company to remove their footwear. Minnie handed out the musical instruments. Then, standing atop a makeshift plinth, Chodd thumbed open the exercise book and proceeded to shriek.

“This is the Last Will And Testament of Lars Talc. I, Professor Lars Talc, a Finn, a polymath, author of numberless books on topics as diverse as anorthopia, bell-ringing, cramp, death, ectoplasm, fireworks, galley-slaves, haplography, Iceland, jam, knuckle-dusters, lemon meringue pie, mortmain, nystagmus, owls, pap, quicklime, ranunculus, sanitation, time-bombs, ullage, vanquishment, whimbrels, xerasia, yeast, and zapateado, I, an accomplished musician, balladeer, and madrigalist, who have in my time excelled as a wrestler, an entomologist, a pirate manqué, a splinterbrain, and a taxonomer, I who have enjoined my fellow Finns to acts of mercy and philanthropy, who have robbed none but given succour to many, who have clambered over mental obstacles with the torch of truth clutched in my fist, I, Lars Talc, Professor of Pandaemonium, moral exemplar, I who would reek of saintliness were there such things as saints, which there are not, I hereby give, devise, and bestow, absolutely and forever, in perpetuity, until the last pale flicker of animate life is stilled and the universe blotted out, I bequeath all my estate and effects, whatever they may comprise, for I neither know nor care, but all of it, every last scrap, to my dear, dear Minnie, who I thus proclaim as my executrix, and if, oh!, misery, she should perish before I do, then the whole lot will instead be bequeathed to a man, a crab-gaited man, a lanky man with a stoop, a man who will make himself known to you by the popping noises he elicits from the thin slit of his mouth, a man who may remain in hiding for years, even decades, during which time my estate will be tied up in formidable legal knots, and chaos descend upon all those who have the gall to claim any part of it, and their lives will be filled to the very brim with woe.

“In witness to the above, I have hereunto set my hand, this teeming day, [date]. The florid, some would say too florid, signatures of my witnesses appear below. Both are in my presence as I write. Pillchain is slumped in an armchair, leafing through a copy of my momentous tome The Glue Of Rascality, a better book than he will ever write. The other witness is a topiarist of renown, who I bumped into at the docks this morning, and is at present fooling about in a striped purple and green cape in my vestibule.

“In turn, I will hand each of them my pen and la!, they will sign their names, and this document will be complete, and I will apply a wad of blotting paper, and shut the book, and place it in my cast iron cabinet, where it will remain for who knows how long, until these final words are screeched by my embalmer in a desolate spinney on the day after my death. You may now remove your cotton hoods and, putting boots, shoes, or sandals back on, go shod, my proxy-screeched farewell ringing in your ears. Farewell!”

Chodd ceased. The mad strumming on the banjos, shamizens, guitars, and ukuleles ceased. The sun burst from behind a cloud. Lars Talc’s will was done.

In 1742 Jacques Benigne Winslow published a book entitled The Uncertainty Of The Signs Of Death. Aloysius Batlip owned a pirated Finnish edition of this important work, to which he referred each time a corpse lay sprawled on his mortuary slab. It was his practice not to allow weeping relatives into the Chapel of Rest until he was quite sure that the body was beyond all hope of resuscitation.

Hence he followed Winslow’s advice to pour vinegar, pepper, and fresh, warm urine into the supposedly deceased’s mouth. But this was merely the first of a battery of tests he carried out. Talc’s cadaver was subjected to a panoply of often ferocious indignities.

Batlip tweaked the Professor’s nipples with Dr Josat’s formidably sharp metal pincers, shocked his ears with hideous shrieks and excessive noises, applied a thermometer to his rectum, rammed burning tapers up his nostrils, melted sealing wax upon his chest, dipped a hammer into boiling water and pressed it into the hollow of Talc’s abdomen, plunged Monsieur Middledorf’s flag-capped needle into his heart, stuck one of Talc’s fingers into his ear to listen for rolling noises, carried out Snart’s anal sphincter test, dusted the groin with kwantod powder, and injected a solution of duggery into the spinal cord. Finally he was satisfied, and with Chodd still acting as his helper, he prepared the corpse for display.

“Cleanse the body, Chodd,” he said, handing his assistant a bar of soap and a mop, “I will gather the substances and equipment.”

Batlip was justly proud of his embalming skills, and had won many cups and trophies from the Institute of Finnish Sepulture. As Chodd, having completed his task, wrung out the mop in a bucket, Batlip plunged a trocar into Lars Talc’s abdomen just above the navel, and thrust it in all directions until he had pierced the stomach, intestines, rectum, bladder, and liver, sucking out bits of tissue, blood clots, food, faeces, intestinal gases, and urine. He then pushed the trocar through the diaphragm and into the chest, lacerating and sucking as it went. Pausing only to snack on a conger-eel sandwich, he pumped preserving fluid into the cadaver, and turned his attention to the face.

When you die, your lower jaw falls downwards and backwards, and the mouth hangs open, giving you the look of a dolt or a dunderpate. With Chodd at his side, Batlip passed a needle and thread from the inner surface of Talc’s lower lip, up in front of his gums, through into one nostril, across to the other nostril, and back again into his mouth behind the upper lip. When the thread was drawn tight, by a fascinated Chodd, the lower jaw was pulled upwards and forwards. Lars Talc looked pensive and wise, and would remain so for a week or two, until his flesh began to rot.

They dressed him in a winding-sheet embroidered with Batlip’s monogram, leaving only his face uncovered. Then they transferred him to the coffin and lifted it on to the slab, having first covered it with a cloth of baize. And there, for the next few days, the great Professor Talc lay in state.