“I think,” said Dobson, at breakfast one foul and rain-sodden Tuesday morning, “It is time we had our own mosh pit.”

Marigold Chew raised an eyebrow.

“Do you actually know what a mosh pit is?” she asked.

“Not exactly,” replied the twentieth century’s greatest out of print pamphleteer, “But I suspect it would be a good use of that part of the garden overhung by laburnum and sycamore and larch. You know that patch o’er which hangs leafage so dense that it is forever in shadow, and is home to brambles and nettles and dockweed. I cannot even remember the last time I sat or stood in it nor even walked through it, nor can I recall ever seeing you doing so, O cherished one. It is unused ground, and no ground ought to be unused on this earth, according to some authorities.”

“Which authorities might they be, Dobson?” asked Marigold Chew.

“I think there is a maxim to that effect in the Maxims of Bombastus Dogend, or I could be thinking of Listerine Optrex, also a great one for maxims. I can check later.”

“So let me get this straight,” said Marigold Chew, marshalling with her fork the last few caraway seeds on her breakfast plate, “You intend to dig a pit in a shady arbour in the garden, and dub it a mosh pit, without any clear understanding – without any understanding at all – of what a mosh pit is?”

“I shall look it up in a thick and exhaustive reference book,” said Dobson, mad with cornflakes.

“So you will be going to the mobile library?” said Marigold Chew.

“That is my plan,” said the pamphleteer, and he got up from the table and proceeded to don his Andalusian Sewage Inspector’s boots.

“Today is Tuesday,” said Marigold Chew, “So the mobile library is in quite a different, and distant, bailiwick.”

“And you think I am going to let that stop me?” shouted Dobson melodramatically as he crashed out of the door into the downpour.

Untold hours later, Dobson came crashing back through the door, sopping wet, with a gleam in his eye and a thin, pained smile playing about his lips, as if he were Ronald Colman shooting a scene for Random Harvest (Mervyn LeRoy, 1942).

“Well, Dobson, what news?” asked Marigold Chew.

Dobson took his pipe from his pocket, crammed into it a thub of Rotting Orchard Fruit ‘n’ Conkers Pipe Tobacco from his other pocket, lit up and puffed, and said:

“I had a deal of difficulty finding the thick and exhaustive reference book I sought. Actually, before that I had a deal of difficulty finding the mobile library itself. There is a new mobile librarian, of wild and untrammelled mien, with an unruly beard, whose grasp of the schedule is weak. He had driven the pantechnicon to quite an unsuitable bailiwick, near cliffs, where the native peasants, having never seen the mobile library before, stood in a ring around it, holding aloft their pitchforks and sticks tipped with tarry burning rags, gawping. I think they may have had it in mind to sacrifice the mobile librarian on a pyre.”

“Gosh!” said Marigold Chew.

“Be that as it may,” continued Dobson, “I barged my way through the seething peasant throng and climbed into the pantechnicon. The wild unruly beardy person was engaged in some sort of haphazard reshelving exercise, oblivious to the peasants outside. The mobile library holdings, including several thick and exhaustive reference books, one of which was critical to my research, lay scattered about higgledy-piggledy. Oh! I was sorely vexed. But I found what I wanted eventually, under a pile of paperback potboilers by Pebblehead. And – “

“You have created a puddle on the floor, Dobson,” interrupted Marigold Chew, “So soaked you are from rainfall. Finish your pipe and mop up the puddle and then you can continue your tale over a nice piping hot cup of ersatz cocoa substitute.”

And it was during the subsequent conversation that the out of print pamphleteer revealed to his poppet that he had indeed discovered the nature of a mosh pit.

“Apparently,” he said, “A mosh pit is an area where gaggles of frenzied teenpersons hurl themselves about in an uncoordinated and rambunctious manner to a soundtrack of improbably loud and thumping and often discordant electrified racket played from an adjacent stage or platform by persons not dissimilar to the denizens of the mosh pit.”

“Yes, I know,” said Marigold Chew, “I could have told you that this morning over breakfast. I assume that now you know what a mosh pit is you no longer want one in your own back garden.”

“Quite the contrary, my sweet!” shouted Dobson with unnerving zest, “I am all the more determined to dig one! Hand me that spade!”

And though it was now dark, and the rain was pouring down more heavily than ever, Dobson was soon enough out in the garden, under the dripping leafage of laburnum and sycamore and larch, digging a pit. Positing that he had taken leave of his senses, Marigold Chew retired to her boudoir to listen to Xavier Cugat And His Orchestra on the wireless.

At some point in the small hours of the morning, Dobson came back indoors. He was covered in mud, as if he had been toiling in the trenches of Flanders fields during the Great War, the cause of the shellshock suffered by Smithy, alias Charles Rainier, the character played by Ronald Colman in Random Harvest (Mervyn LeRoy, 1942). Marigold Chew was fast asleep, but she was woken by a repetitive dull thumping noise, as of bone cushioned by flesh bashing against wood, over and over again. She went downstairs to find Dobson slumped at the kitchenette table, repeatedly thumping his forehead against its polished wooden surface.

“Whatever is the matter, Dobson?” she asked.

Dobson looked up.

“The mosh pit is dug, my dear! It needs but a complement of frenzied teenpersons to be deposited within it. That is my quandary, that the reason for my despair.”

“Please explain Dobson, you have me utterly befuddled. Though it be the middle of the night I am going to put the kettle on for a nice piping hot cup of powdered milk slops enriched with filbert nut flavouring. Pray continue.”

“Well,” said Dobson, “It was only when I had finished digging the mosh pit, and clambered out of it, and stood back to admire my work in the brilliant illumination of Kleig lights, that I realised the fatal flaw at the heart of my design.”

“Which is?” asked Marigold Chew.

“We have not space in the garden sufficient to erect a stage or platform next to the mosh pit,” moaned Dobson, “Thus nowhere to assemble a grouplet of persons to provide the necessary soundtrack of improbably loud and thumping and often discordant electrified racket to which frenzied teenpersons so minded will mosh.”

“Look on the bright side,” said Marigold Chew, “We may not have our own mosh pit, but now we have an all-purpose pit. There is a myriad of usages to which it could be put. I can think of several immediately, but I will refrain from telling you right away. I think you need a disinfectant bath and a good night’s sleep.”

“Perhaps you are right, buttercup,” said Dobson, “And in any case there may be such an activity as moshing for the deaf, or moshing to the sound of a lone piccolo, or other types of moshing yet unimagined by frenzied teenpersons, and by unfrenzied teenpersons too. Tomorrow I shall go to the mobile library again, assuming it has not been shoved over the cliffs by the baffled and menacing peasants, and I shall undertake further and more rigorous research..”

“That is an excellent idea, Dobson,” said Marigold Chew, “But before plunging into your disinfectant bath, just tell me one thing. Why on earth did you want to have frenzied teenpersons hurling themselves about in an uncoordinated and rambunctious manner to a soundtrack of improbably loud and thumping and often discordant electrified racket in your own back garden in the first place?”

Alas, whatever Dobson said in reply was drowned out by the piercing shriek of the now boiling kettle.

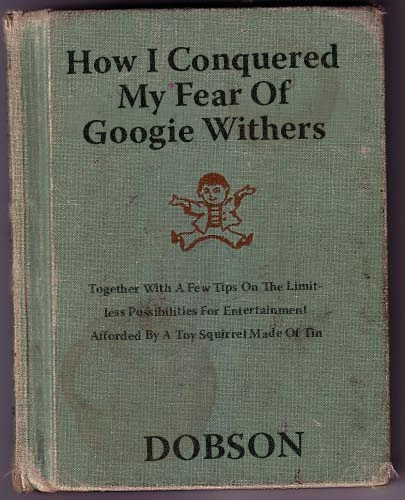

Some days later, Marigold Chew hoicked the spade and filled in the pit under the leafage, still dripping with rain, of laburnum and sycamore and larch, and strewed over it brambles and nettles and dockweed. Never again did the word “mosh” ever pass Dobson’s lips. Other matters had attracted his attention, as related in his pamphlet How I Witnessed The Sight Of A Wild And Unruly Bearded Mobile Librarian In Hand To Hand Combat With A Snarling Gaggle Of Brain-Bejangled Peasants (out of print).

Originally posted in 2011.