Category Archives: Things I Have Learned

Calendar

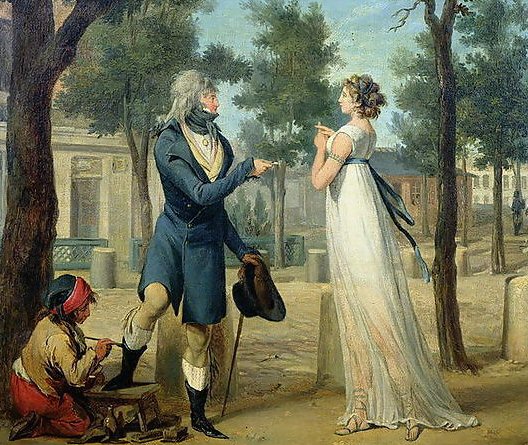

For no pressing reason – a note to myself as much as anything – I thought I would post the names of the months of the French revolutionary calendar, together with the information that they were devised by Fabre d’Églantine, poet and dramatist, who ended up under the guillotine (there’s a surprise) and that the calendar itself was in use from November 1793 until the end of 1805, although it was deemed to have begun on 22 September 1792. So, those months then:

Vendémiaire, Brumaire, Frimaire, Nivôse, Pluviôse, Ventôse, Germinal, Floréal, Prairial, Messidor, Thermidor, Fructidor.

I have absolutely no idea how those names translate into Esperanto, but I suppose if you bung an “o” on at the end of each you won’t go far wrong.

ADDENDUM : Mention of the guillotine leads me to add that the first models of the new improved execution engine were constructed by Tobias Schmidt, by trade a maker of harpsichords.

The White Technique

“Overhead, there would sound a curious wailing from Father Bernard’s room. When I first heard this sharp cry break out on Monday morning, I had supposed that Father Bernard was either having a fit or whipping himself. [Eric] Gill, however, had quickly reassured me. It appeared that Father Bernard’s vocal cords were not all they might be and that he was studying a new method of voice-production, invented by a man called White, in which the vocal cords were dispensed with altogether and the notes produced by expansion and contraction of the sinuses. This did not seem to me possible.”

Rayner Heppenstall, Four Absentees (1960)

A Pernicious Brain-Softener

“The initials stood for ‘Present Question’. PQ was essentially a conference-holding organisation, devoted to the idea of synthesis… The distinguished lecturers were not themselves psychologists. They had their own terminologies, historical, anthropological, religious, scientific, literary, artistic, political. Their views were the opposites to be reconciled… Then there was ‘wholeness’ and ‘becoming a person’, but otherwise not much Jungian undertow, certainly not enough to bother me. With the whole idea of the thing, I was intellectually uninvolved. It was simply that every now and then I would get on a train to Oxford and spend a week gassing with distinguished chaps, many of them amusing. Most of the time, my interests lay decidedly elsewhere. Only later did I begin to think of Jung as perhaps the most pernicious brain-softener of our time.” – Rayner Heppenstall, The Intellectual Part (1963)

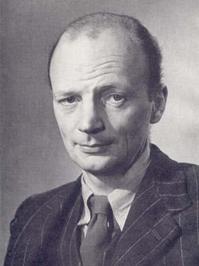

Heppenstall (1911-81) was an interesting character. In addition to writing novels, memoirs and criticism, he was an early English enthusiast – and translator – of Raymond Roussel. There is an essay about him by G J Buckell here, which points out that he is forgotten and out of print, and suggests one reason for the neglect is that he grew increasingly reactionary with age. Buckell says the last novel, The Pier, is “an uncomfortable diatribe… indicative… of a psychological collapse”. On the contrary, it is a small masterpiece. It is not clear to me why the espousal of reactionary views is, in and of itself, evidence of mental instability.

Here is Heppenstall in fine form, again from The Intellectual Part:

“It had, as a matter of fact, been on starting to read a poem by T S Eliot that I first questioned the good sense of writing poems at all. That had been in the autumn of 1940… A copy of The New English Weekly had come in the post. It contained a long new poem, East Coker, by T S Eliot. I turned to the poem with some eagerness. It began:

In my beginning is my end…

“I flung the paper across the room. It was like a signature tune. The poem might just as well have begun:

This is T S Eliot speaking…

In due course, I picked up the paper and read the rest and no doubt liked some of it, as I do now. It is not, after all, in that poem that Mr Eliot bids us so oddly to pray for fishmongers.”

Rayner Heppenstall

ADDENDUM : Speaking of prayers for fishmongers, Eliot may have been thinking of this.

Gravelly Pightles

The first thing of note I learned on Christmas morning is that in Berkshire, to the south-west of the village of Hermitage, is a small area of land with the sonorous name Gravelly Pightles.

Perhaps a kindly Berkshireist Hooting Yard reader with nothing better to do could hie over there with a camera and photograph it, preferably in black and white, during a drizzle?

How To Get Up In The Morning

“On Thursday morning, he awoke heavy, confused and splenetic. On Friday, he remembered a friend’s prescription that, on arising, he should cut two or three brisk capers round the room, which he did and found attended with most agreeable effects. It expelled the phlegm from his heart, gave his blood a free circulation and his spirits a brisk flow, so that he was all at once made happy. He resolved to persist in the exercise.”

The James Boswell approach to getting up in the morning, as noted by Rayner Heppenstall in Reflections On The Newgate Calendar (1975).

A Burning Goat In The North

Good heavens!, or, as it might be, Lumme guvnor, what a turn up, eh? I fear we must conclude that Swedish civic officials are peculiarly inept in the matter of yellow straw goat safety measures.

Machines Of Interest, Number One

“… they went up to a machine behind whose glass were small and crude images of moustached footballers.”

Patrick Hamilton, The West Pier (1951)

A Bee Fact

I didn’t know this. In Koba The Dread, Martin Amis tells us: “Hitler’s father (somehow very appropriately) was more and more obsessed, as he grew older, by bee-keeping.”

The Way We Were

Tempora mutantur, nos et mutamur in illis. The way things used to be, unimaginable now…

“Probably the most curious by-product of the famous Palmer poisoning case was a book, published in London some four years after the doctor’s execution [ie, in 1860 or thereabouts] which translated the entire trial record, along with an account of Palmer’s sporting activities, into classical Greek.”

From Victorian Studies In Scarlet by Richard D Altick (1970)

Green Apple

Green Apple Books on Clement Street in San Francisco had been recommended to me as one of the finest bookshops it would ever be my pleasure to visit. As it happened, I was staying five minutes’ walk away, so I availed myself of a number of opportunities to pop my head in the door. They sell both new and used books, and we all know that a splendid selection of reasonably-priced secondhand books is basically what makes life worth living. Here is a list of my purchases, carted back to Blighty to take their places on the tottering bookshelves at Haemoglobin Towers. In no particular order:

H L Mencken : Disturber Of The Peace by William Manchester

Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle

The Post-Office Girl by Stefan Zweig

Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner

The Coming Race by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

The Sinking Of The Odradek Stadium by Harry Mathews

The Case Of The Persevering Maltese : Collected Essays by Harry Mathews

Schnitzler’s Century : The Making Of Middle-Class Culture 1815-1914 by Peter Gay

Treatise On The Gods by H L Mencken

The Sardonic Humour Of Ambrose Bierce edited by George Barkin

Lost Prince : The Unsolved Mystery Of Kaspar Hauser by Jeffrey Masson

Raymond Roussel And The Republic Of Dreams by Mark Ford

Signs Of The Times : Deconstruction And The Fall Of Paul De Man by David Lehman

The Making Of Americans by Getrude Stein

High In The Air, Amused

“I have already been subject to abuse and physical attack (pelting with so-called ‘organic’ vegetables etc.) because of my genetic engineering experiments: eg, my production of a new type of electronic bread, enriched with GMOs, which turns into toast on a voiced command. – Paul Ohm, Atomdene, Edgbaston”

From Peter Simple’s Century by Michael Wharton (1999) – my aeroplane reading yesterday, crossing the Atlantic. I have never before read the uberreactionary Wharton, who is extremely funny and, I learn, was noting the activities of Aztec fundamentalists long before me.

Theophrastus

“[Theophrastus] left behind to Posterity several monuments of his divine Wit, of which I think it but requisite to give the Reader a Catalogue, to the end that thereby it might be known how great a Philosopher he was…

“… Of Nature. Three Books of the Gods; one of Enthusiasm; an Epitome of Natural Things; A tract against Naturallists; one Book of Nature; three more of Nature; two Abridgments of natural things; eighteen more of Natural things; seventeen of various Opinions concerning Natural things; one of Natural Problems; three of Motions; two more of Motion; three of Water; one of a River in Sicily; two of Meteors; two of Fire; one of Heaven; one of Nitre and Alum; two of things that putrifie; one of Stones; one of Metals; one of things that melt and coagulate; one of the Sea; one of Winds; two of things in dry places; two of Sublime things; one of Hot and Cold; one of Generation; ten of the History of Plants; eight of the causes of them; five of Humours; one of Melancholy; one of Honey; eighteen first Propositions concerning Wine; one of Drunkenness; one of Spirits; one of Hair; another of Juices, Flesh and Leather; one of things the sight of which is unexpected; one of things which are subject to wounds and bitings; seven of Animals, and another six of Animals; one of Man; one of Animals that are thought to participate of Reason; One of the Prudence and Manners, or Inclinations of Animals; one of Animals that dig themselves Holes and Dens; one of fortuitous Animals; 1182 Verses comprehending all sorts of Fruits and Animals; A question concerning the Soul; one of Sleeping and Waking; one of Labours; one of old Age; one of Thoughts; four of the Sight; one of things that change their Colour; one of Tears entituled Callisthenes; two of hearing; one of the Diversity of Voices of Animals of the same sort; one of Odours; two of Torment; one of Folly; one of the Palsie; one of the Epilepsie; one of the vertigo, and dazling of the Sight; one of the fainting of the Heart; one of Suffocation; one of Sweat; one of the Pestilence.”

From The Lives, Opinions & Remarkable Sayings Of The Most Famous Ancient Philosophers, translated “by diverse hands” from the Greek of Diogenes Laertius (1688), and quoted in The Chatto Book Of Cabbages And Kings : Lists In Literature, edited by Francis Spufford (1989)

He’s A Proper Caution, That Arlok

I am deeply grateful to Odd Ends for posting a link to Astounding Stories Of Super-Science, January 1931. Why so? Readers already know – or ought to know – that I am no aficionado of SF, though oddly it seems some SF-minded persons are keen on my work. Mine not to reason why.

There is one writer in the field, however, cruelly neglected, whom I adore, unreservedly. I speak of course of Hal K Wells, a man whose prose was forever pitched at hysteria level. Lap up those adverbs and adjectives!

I have just realised that I raved about Mr Wells as recently as last April. No doubt my forgetfulness can be adduced to the shuddering miasma of crepitant dread to which my brain has been reduced by reading this newly-posted story, entitled The Gate To Xoran:

The attack of the Xoranians was hideously effective. Clouds of dense yellow fog belched from countless projectors in the hands of the bluish-gray hosts, and beneath that deadly miasma all animal and plant life on the doomed planet was crumbling, dying, and rotting into a liquid slime. Then even the slime was swiftly obliterated, and the Xoranians were left triumphant upon a world starkly desolate.

“That was one of the minor planets in the swarm that make up the solar system of the sun that your astronomers call Canopus,” Arlok explained.

“Our first task in conquering a world is to rid it of the unclean surface scum of animal and plant life. When this noxious surface mold is eliminated, the planet is then ready to furnish us sustenance, for we Xoranians live directly upon the metallic elements of the planet itself. Our bodies are of a substance of which your scientists have never even dreamed – deathless, invincible, living metal!”

You know you should just stop whatever else you are doing and go and read the whole brain-bedizening story right now. Then unjangle your nerves with a nice cup of piping hot tea.

NOTE : Checking the link back to that April postage, I have noted – not for the first time – some kind of formatting problem in older posts resulting in the appearance of extraneous characters. I think this happened after the tumultuous and terrifying hacker attack of some months ago. Steps will be taken, gingerly, to eradicate these alien hoofprints. Until then, just try to ignore them.

Kokoschka And Toads

“When one opens a door there’s something on the far side that was not there before. I had a premonition that it would be irrevocable when, from a crate filled with wood-shavings or curly paper, she unpacked the death mask of her late husband. Even when they were drawing up the ground plan of our future house some had thought the choice of site a dubious one, for there was an underground spring there in which the foundations would some day be awash. But with much labour and expense the water was diverted. There was another disagreeable impression I will not pass over. It was like this. When we went to look at the house, which was just being finished – the beribboned tree already set on the rooftop by the master carpenter – there, in the future bathroom, where the spring had been piped and made to provide our water-supply, there was an aquarium such as people use for ornamental fish. It was full of hideous creatures swirling around in clusters. This was the visiting card of someone I loathed, a candidate for the lady’s favours, a zoologist who had made a name for himself with experiments in cross-breeding. Presumably he had caught these toads here in order to take them to Vienna and use them for his experiments in the Institute in the Prater. A few days earlier he had committed suicide – this I learnt subsequently. So this was his bequest to us. As quickly as I could I emptied the tub full of batrachians into the swampy field that had come into existence all round the house since the previous winter. What I should have liked best would have been to spare her the sight of these fat-bellied creatures, for she was pregnant. Instead she had to watch and see how each of the yellowish, disgusting toads of the larger sort, the females, carried one of the smaller, greenish males to the water on her back. In coupling with the females the males had fastened on to their sides with their sucker-feet. It was early spring.”

From A Sea Ringed With Visions by Oskar Kokoschka (1962) Though he does not name her, “she” is Alma Mahler – the actual woman as opposed to the later rag doll.