Over at The Dabbler today, I resurrected my playlet about the Fripps, and the invention of an entirely new kind of cake. Of more import, perhaps, is the comment from Brit – the third one down – the implications of which, I must say, are quite terrifying. Please have a nerve tonic ready to glug as soon as you have read it. You’ll need it.

Monthly Archives: August 2014

Our Man In Ulm, Still

Another dispatch from our man in Ulm:

I am still in Ulm. I may be here for the foreseeable future. Yesterday I told you that I was stricken, after lunch, by jellybrain and cork-in-the-ears. My symptoms have abated not one whit. I am not entirely sure what a whit is. Perhaps it is related to a squib which, you might have noticed, in your reading over the years, is invariably described as damp. I have never come across a squib that was moist, or wet, or soaking wet, or drenched, let alone one that was dry, or bone dry. No, a squib is always damp. Can the same be said for the whit?

You might be waiting for me to apologise for digressing, impatient as you must be to hear of the latest doings in Ulm. But apologise I will not. I have much else to contend with, such as my medical condition(s) and that gas leak (still not fixed). Added to which, there has been a bittern storm over the city, the sky is almost black with bitterns, and I have had to light a candle to see by. Then there is the question of whits and squibs, and the revelation that not a single gazebo in Ulm is owned by a beekeeper, at least not legally. There may be squatters, off the grid.

So I think it is plain that being your man in Ulm is no picnic. I cannot remember when last I went on a picnic. This is made all the more galling when one thinks how easily available are sausages so suitable for picnics. Instead I must eat these sausages indoors, or at best at a table on a pavement outside a café. Would it count as a picnic, I wonder, if I spread a blanket on the pavement, a few feet away from the table, and sprawled there, eating my sausages? I think I would be liable to arrest, as a pavement nuisance.

That is all I have time to babble on about today, from Ulm. Some might describe this dispatch as a damp squib. If so, don’t blame me. Blame the bitterns, whose stormy appearance in the sky over Ulm has blotted out the sun, and made us all a little more prone to gloomy thoughts. The pig in his sty is a happier fellow.

Over and out, your man in Ulm.

Our Man In Ulm

Our man in Ulm has sent this report from the Festival of Argumentative Music in Ulm:

The annual Festival of Argumentative Music in Ulm has become a highlight on the calendar for lovers of grumpy German improv jazz, and this year they received a special treat with a performance by grumpy German improv jazz titan Horst Blot. With his usual septet augmented by glockenspiel, steam hammers, Japanese cardboard trombone, and an electronically-enhanced janitor’s mop, Blot devoted his entire four-hour set to a startling reinvention of the old jazz standard Chutney On My Spats.

Unfortunately, I was not able to attend the concert. I had a very trying day. In the morning I had an ague and the quinsy, and then shortly after lunch I was stricken by jellybrain and cork-in-the-ears. In addition, I had to deal with a gas leak and a letter demanding the return of an overdue library book. The final straw was the discovery that my press pass had expired, meaning I would have to pay out of my own pocket for a ticket to the Festival. Horst Blot may well be a grumpy German improv jazz titan, but I am not going to open my wallet for him.

Instead, I waited until the next day to read the review in Godawful Racket magazine. What a load of codswallop! It was written by Primrose Dent, who opined that the music was, among other things, searing, bippety-boppety, tough, chewy, Machiavellian, plinky-plonky, mordant, splenetic, sunlit, dappled, goosebumpy, tenebrous, and “a bit like a choc ice”. In other words, she simply pulled a load of adjectives out of a bag and strung them together.

Now I have done exactly the same thing, in some of my reports from Ulm, in the days when I used to have a valid press pass. I wrote out hundreds of adjectives on hundreds of scraps of paper, stuffed them into a pippy bag and then plucked out a few dozen each time I had to write an article on, say, the bus stops of Ulm, or the gazebos of beekeepers in Ulm, or indeed an earlier Horst Blot concert at the Festival of Argumentative Music in Ulm, where he played a shorter, three-and-a-half-hour version of Chutney On My Spats, without the glockenspiel, steam hammers, Japanese cardboard trombone, and electronically-enhanced janitor’s mop, but with a steam glockenspiel, a Japanese cardboard mop, and a bowl of rice pudding. My articles may have been codswallop too, but they were emotionally-wrenching codswallop which elicited great heaving sobs from my readers. I know this because they used to write to me, although I was never able to read their letters, smudged as they were with salty tears.

When I have recovered my wits I shall write a letter to Godawful Racket magazine pointing out that Primrose Dent has been deaf as a post since that episode in the wind tunnel at the aerodrome. She also puts her adjectives in the wrong sort of bag.

Over and out, Your Man In Ulm.

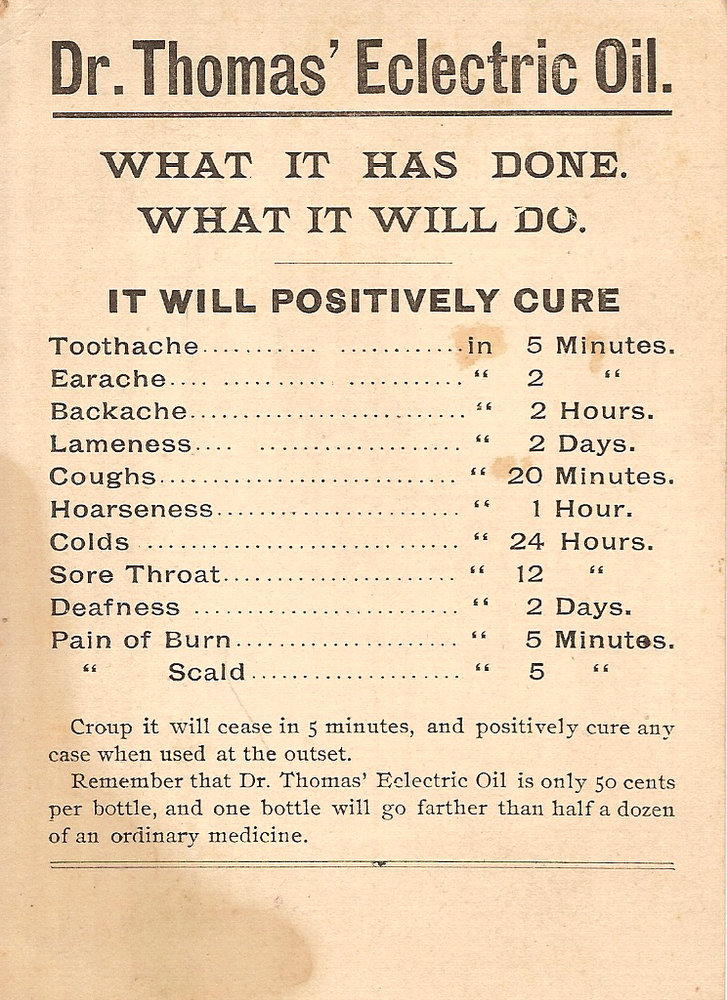

Eclectric Oil

Speckles And Splodges And Smudges

Two of the answers in today’s Guardian crossword were SPECKLE and SPLODGE. This put me in mind of Dobson’s pamphlet A Comparative Study Of Speckles And Splodges And Smudges (out of print). It is one of his most exasperating works. The exasperation lies, in the words of the critic Rappa Kohoutek, in the fact that

Dobson opens with the grand statement that “the speckle, the splodge, and the smudge are each of them wholly discrete and different phenomena, and to muddle them up is not merely ignorance, but dangerous ignorance. Wars have been fought, and men have died, for failure to distinguish between the three”. This is exasperating on two counts. First, in the eighty pages of microscopically tiny print that follow, the pamphleteer himself neglects to explain the difference between speckles and splodges and smudges. Second, nor does he provide a single example of the war and death he so melodramatically warns the reader of and I am going to let this sentence run on because I hate to end with a preposition even though to do so is completely defensible unless one is up against the most rigorous of pedants armed, as certain pedants are, with a hammer of correction.

It is perhaps worth noting here that Rappa Kohoutek bore several dents in his head, made by one such “hammer of correction” wielded by a particularly rigorous pedant whose path he used to cross occasionally. The critic liked to spend his mornings at a sophisticated pavement café sipping from a glass of bengkht. Along the pavement would come the pedant with his hammer, lashing out with what used to be called “gay abandon”.

The dents in his head did not effect Rappa Kohoutek’s critical acumen, however, and we must agree with his judgement about this particular Dobson pamphlet. In a sense, we have no option but to agree with him, and trust him, because we are never likely to read the work itself. As he points out, the text of the pamphlet is microscopically tiny, and he is not exaggerating. It is so tiny that the average reader would ruin their eyesight before getting to the end of the preface and acknowledgements. Rappa Kohoutek explains in an afterword to his own essay that he was able to read all eighty pages of text because his sense of vision was inexplicably enhanced by one of the blows to the head he received from the pedant’s hammer of correction. In a further afterword to a second printing of his essay, the critic relates how a subsequent blow from the same hammer restored his sight to its previous mild myopia:

And so I shall never again be able to read Dobson’s pamphlet on speckles and splodges and smudges. But quite frankly, why on earth would I want to? It is absolute drivel.

A hugely magnified copy of Dobson’s pamphlet has been made available by the Dobson Pamphlet Magnification Commission, but so tiny is the text that in spite of the hugeness of the magnification it is still pretty much illegible to any human eye.

Fruit Query

My brother poses a question:

Why are there no bananas in Poland?

Answers on a postcard, please …

Weird Oranges

I went to the greengrocer’s and bought a bag of weird oranges. I say bag, but it was really a net, spun from some kind of red synthetic fibre, fastened with a dinky metal clasp. The net contained, by my reckoning, half a dozen oranges. And weird they were, though my intention had been to buy blood oranges. I was persuaded by the patter of the greengrocer to take the weird ones instead. The curious thing about his patter was that, by the time I was a few yards along the street, clutching my net, on my way to the park, I was unable to recall a single word of it. Why was I carrying weird oranges instead of the blood oranges I had wanted? I had no idea, but nor did I seem able to retrace my steps. I hurried on towards the gates of the park as if impelled by a force outwith my perception.

Arriving at the park, I made my way to my usual bench anent the duckpond. The ducks looked forlorn and ill-tempered. I discovered that it was impossible to unfasten the clasp on the net with my bare hands. It was, as I said, dinky, about the size of say eight standard stationery staples impacted together laterally. I picked at it with my fingernails but could get no purchase. I then tried to tear a slit in the net itself. God knows what the fibres were made of. Whatever it was resisted my increasingly energetic attempts to rend it. I gave up when my fingers were red with bloody stripes and my hands were shaking.

My plan had been – oh, it hardly matters, does it?, now it was so plainly abortive. In any case, I reflected, as I sat on the bench panting from my exertions, my plan probably would not have succeeded anyway, since I had been coaxed into buying weird oranges instead of blood oranges, the latter being a crucial element in the plan. A teal – or it might have been a merganser – paddled to the edge of the duckpond and fixed me with a look of reproach. I spat on the ground, and kept on spitting, until I had exhausted my phlegm.

Then I went a-trudging, without aim or purpose, through the park and along the lane past the railway sidings, up into the hills, those damnable pointy hills. I left the net of weird oranges on the park bench, from which they were snaffled, before the day’s end, by a wolf. It was a weird wolf, so at least there was some kind of neatness to what was otherwise a most jambly-jumbly day.

Destructive Dusty

According to a new biography, Dusty Springfield would order deliveries of boxes of crockery, which she would then smash against a wall in a frenzy of hysterical destruction.

Cat Versus Booby

I have been thinking, as I sometimes do, about the ineradicable stupidity of certain animals. These thoughts were prompted, today, by the newsagent’s cat. It really is a bewilderingly stupid cat. I then found myself pondering the blue-footed booby, a bird which gives the impression of being as witless as any cat. The newsagent does not have a pet booby, alas, so I had to make do with examining pictures.

A blue-footed booby. You already know what a cat looks like.

A blue-footed booby. You already know what a cat looks like.

I then began to wonder which one is the more stupid, the cat or the booby. Surely the best way to find out would be to pit one against the other in a (lack of) intelligence test – a “brain-off” between the newsagent’s cat and a blue-footed booby. Unfortunately, it was at this point that I learned – by consulting my copy of Dobson’s Bumper Book Of Facts About Things The Lower Extremities Of Which Are Blue (out of print) – that the blue-footed booby is not native to these shores. Apparently they are to be found from the Gulf of California down along the western coasts of Central and South America to Peru.

The wonders of space age technology mean that their far distant habitat need not deter me. All I need is for a Hooting Yard reader resident in that part of the world to get hold of a blue-footed booby and stick it in front of a computer. I will do likewise with the newsagent’s cat, and we can link up using Skype. We can then subject them to a series of tests, the one against the other, cat versus booby, to determine which one is the thickest.

I will post an account of the contest, and its results, as soon as we have managed to conduct it.

Bracing Walks In Bleak Settings

Dear Mr Key, writes a correspondent I have just made up, I know you are a constant reader who always has “a book on the go”, as they say. It would interest me to know how you go about choosing which book you are going to read next.

In the normal course of things, I would be hard put to give a straightforward answer to that question. Like most of us, I suspect, I alight upon books for all manner of different reasons, not always rational. Today, however, I can say definitively that I decided on my current reading simply because I saw a photograph in the newspaper of Michael Gove reading it.

When he was sacked as Education Secretary the other week, the Grauniad had a double-page spread on Gove, much of which was of course devoted to attacking him. Among the accompanying photos was one of Gove “at a literary festival”, where he was shown reading from – the title was clearly visible – The Lost World of British Communism by Raphael Samuel, essays written in the 1980s but published in book form (by Verso) in 2006.

I immediately wanted to read this book, and eventually got round to borrowing it from the library. Just a few pages in, and it looks very promising. In the preface by Samuel’s widow Alison Light, I learn that among the treats in store are such details as

what Communists sang or watched at the cinema; what they wore, (open-necked shirts, if they were men, with a pen or pencil prominently displayed in the breast pocket; jumper, slacks and ‘sensible shoes’ if they were women); how Party members comported themselves in public (they were urged to be neat and clean); where they went on holiday – if indeed they took holidays – preferring ‘bracing walks’ in bleak settings; the content and feel of their homes, which were usually uncomfortable, with a small shrine of books and the garden left a wilderness, the author tells us, for want of ‘personal time’.

I shall report further snippets of interest as I read on. Meanwhile, if any readers are able to provide further photographs of Michael Gove reading particular books, I will be very grateful.

Cheese Horror

“The horror that whole families entertain of cheese is well known.”

A potted history of swoons, shudders, convulsions, and dread in my cupboard this week in The Dabbler.

Captain Nitty’s Attribute

Like a saint in a medieval painting, Captain Nitty bore an attribute. Saint Clement, for example, is usually shown with an anchor, Saint John Chrysostom with bees, Saint Dunstan with a hammer and tongs, and Saint Vedast with a wolf carrying a goose in its mouth. Captain Nitty was often to be seen with a handful of breadcrumbs.

There are several photographs of Captain Nitty, taken by the Pointy Town High Street snapper F X Duggleby, in all but one of which his attribute or emblem is present and correct. Captain Nitty holds out his open palm, piled with breadcrumbs, as if proffering them to the viewer. (The exception is the picture of Captain Nitty pretending to fly. He is wearing a pair of wings made out of corrugated cardboard, satin and tat, and gazing into the middle distance with a look of startling stupidity. The chains with which he is attached to the ceiling of Duggleby’s studio are clearly visible, despite the photographer’s efforts to bleach them out with bleach.)

There are two different stories given as the origin of Captain Nitty’s traditional association with a handful of breadcrumbs. The first is that our hero was regularly sent on manoeuvres to a municipal park where insurgents, bent on toppling the regime, were said to use the flowerbeds, with their dazzling splurges of lupins and hollyhocks, as places of concealment. Anent the flowerbeds was a pond in which teal, mergansers, pintails and swans were rife. Soft-hearted – and, by some accounts, soft-brained – Captain Nitty liked to feed the ducks and swans by scattering breadcrumbs upon the surface of the waters. After the regime was toppled, he took much of the blame, “distracted by ducks” in the words of the official charge sheet. Unlike a saint in a medieval painting, Captain Nitty was not martyred, unless one considers a sentence of several months potato-peeling duty a martyrdom.

The other story is vastly more complicated and impossible to summarise. Readers would do better to study the seven-volume novel sequence Game Of Breadcrumbs, making notes all the while in the margins. Those of you without the patience or ability to read can instead watch the television adaptation, which has won a mantelpiece’s worth of awards, including the Silver Bauble for Best Swan and the F X Duggleby Memorial Pot for Most Innovative Use Of Bleach.