Let us nip back to the seventeenth century, to the village of Britling, and watch Fly Debate Roberts in action. Roberts, you will recall from your assiduous reading of Hooting Yard postages yesterday, was a screamer in a preaching-barrel. At least, that is how he was portrayed in the pamphlet A Word To Fanatics, Puritans and Sectaries; or, New Preachers New (1641).

Though he took naturally to screaming, especially when it was his turn in the barrel, Roberts won his nickname by dint of his great skill in debate, specifically in debate with flies. Every Thursday, he would commandeer a big barn in Britling, and coax and cajole the villagers to gather therein. Given the squalor and misery and sheer drudgery of life in Britling at that time, most people were only too willing to attend. There was certainly no lack of flies to challenge in debate, for what with all the rustic filth and muck and rot Britling was rife with flies. Roberts was particularly given to debating with blow-flies, and, once the villagers had settled and the hubbub had died down, he would select one particular blow-fly among those infesting the barn. The topic of debate was invariably an abstruse point of theology, of which the following is a typical example:

That this barn agrees with the motion that Man is made in the image of God, whereas the blow-fly is an emissary of Beelzebub.

Roberts would then harangue the fly for more than an hour, his voice rising to screaming pitch so that the dimwits and noodleheads in the audience, of whom of course there were many, could be forgiven for thinking they were attending, not a debate, but one of his screamings from the preaching-barrel. Wiser heads noted the absence of the barrel, and the presence of the fly. At the end of his tirade, Roberts invited the fly to respond. Being a fly, of course, and incapable of human speech, it remained silent, save for the irritating buzzing noise it made as it darted hither and thither, haphazardly, within the barn. Roberts claimed this as a victory and proposed that the fly be put to death, as the loser in the debate and as a representative of the Devil. The villagers, provoked into a frenzy by his words, formed a fearsome throng, leaping and cavorting around the barn armed with sticks and pebbles and rolled-up pamphlets, trying to swat and slaughter the fly. Often they were too stupid to recognise the individual fly Roberts had selected for debate, and swiped at the nearest tiny airborne speck.

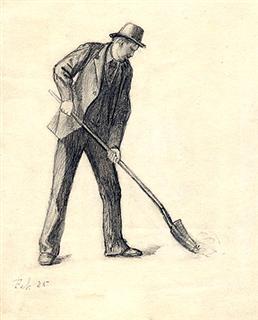

Seventeenth century flies, including the blow-fly, were almost identical to modern flies, and it would take an extremely learned entomologist to spot the minimal differences between them. I’m not an entomologist myself, so I am unable to pinpoint what tiny evolutionary changes may have occurred in the past four hundred years, if any. But one thing we all know about flies is that they move much, much faster than humans. If we can for a moment imagine ourselves inside a fly’s head, it is easy to picture that a crowd of seventeenth century peasants, bent on our murder, and pursuing us within the confines of a barn, will appear as if in slow motion. We have plenty of time, as we watch a villager lumbering towards us, armed with a small agricultural hand-tool, simply to flit out of the danger zone. Even as the peasant is swinging his arm with deadly intent, we have zoomed over to the other end of the barn and are happily regurgitating viscous goo onto a toothsome rotting morsel. If you have difficulty seeing this in your mind’s eye, I recommend you watch The Fly (David Cronenberg, 1986) in which Jeff Goldblum illustrates precisely what I am talking about.

Fly Debate Roberts himself, apparently, declined to take part in the attempted fly-slaughter. He was, as a preacher, a man of words, or rather screams, not a man of action. It was enough for him to know that he had provoked the villagers into a murderous, and Godly, frenzy. He slipped out of a side door of the barn and spent the rest of Thursday with his fellow Britlingite screamer, Be Faithful Joiner, probably engaged in a bit of cooperage. Those preaching-barrels were subject to much wear and tear, and needed proper care and maintenance.

At some point it must have struck Roberts that Thursday after Thursday, the number of flies in the barn never seemed to get any smaller. We do not know if he actually bothered to do a count, and he was never on hand to witness the peasants’ killing frenzy, so he had no idea of their success or lack of it. What was plain, however, was that the emissaries of Beelzebub were far from being eradicated. It was then that he devised his fly-tether.

The Roberts Fly-Tether was basically little more than a thin piece of string, looped at both ends. One loop was attached to a nail hammered into an upright post in the barn. Shortly before the start of the Thursday debate, Be Faithful Joiner, who was quick with his hands, would pluck a blow-fly out of the air, and tie the other loop around one of its tiny legs. The fly would then have to squat on the post, unable to go buzzing and darting around the barn. This made the debates far more exciting, as even the densest and most brainless of the villagers could work out exactly which fly Roberts was challenging. They no longer had to cast their eyes around, foolishly, causing giddiness. Use of the fly-tether also changed the manner in which the debates ended. The fly’s silence was no longer met with a scene of violent if pointless havoc. Instead, Fly Debate Roberts himself, having called for the death of the fly, would take a huge iron hammer and crush his opponent beneath it with a single mighty, righteous, Godly blow.

In the next part of this series we shall take a look at More Fruit Fowler of East Hadley. Fowler accumulated more fruit than anyone before or since. But what did he do with it all? That is the question we hope to answer.

A blow-fly, losing a debate with Fly Debate Roberts