I have never watched a single episode of the BBC soap opera EastEnders, so I had no idea who Cockney matriarch Lou Beale was. I do, however, read obituaries with great interest, including those of people of whom I have never heard. And when reading the Guardian obituary of Anna Wing, the actress who played Lou Beale, I learned that “between 1953 and 1960, she was the partner of the surrealist poet Philip O’Connor” and “she encouraged [him] to write his first book, the extraordinary Memoirs of a Public Baby (1958)”.

I had never heard of O’Connor either, and my interest was piqued – rightly so, I realised, when I read his 1998 obituary in The Independent. Here I learned, among other things, that his mother abandoned him twice during his childhood, and the second time

he was again adopted, this time by a one-legged bachelor civil servant who wore size 13 boots and owned a small wooden hut on Box Hill near Dorking

and that

The impression that he created as a young man in wartime Fitzrovia was of utter precariousness. As thin as a skeleton, his face already eroded, his smile never calm, he lived off doughnuts and Woodbines, ogled at women and spoke in cryptograms, spoonerisms and jingles, delivering sentences backwards and falling about in drunken exhilaration

and

Many people knew him simply as The Man Who Stood Behind The Door And Said “Boo!” To T.S. Eliot

Who could read those snippets and not want to read the Memoirs? So I borrowed a copy from the library, and am already delighted, by page 35, to learn that Philip O’Connor had “a lasting fear of monkeys . . . feeling horribly near to them and that I have a secret they might discover which would involve me in some unconscious activity consequent upon the discovery of a bond between us.”

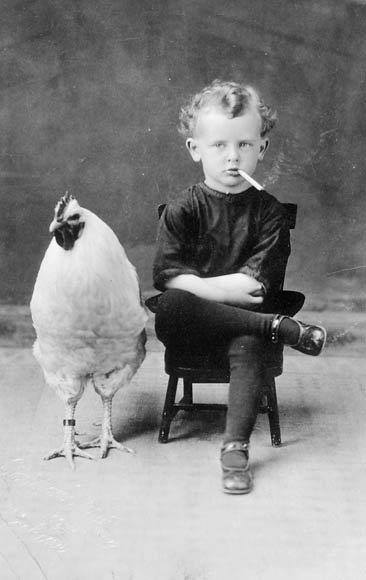

Self-consciously “bohemian” drunkard poets are tiresome, particularly when convinced of their own genius, and no doubt in person O’Connor was – as Stephen Spender says in his introduction to the Memoirs – “a menace”. But they can also, sometimes, write wonderful books, and Memoirs Of A Public Baby – what I have read of it so far – is one. Bear in mind, too, that the Independent obituary notes that O’Connor “dabbled interestingly with chickens”.