A while ago I waxed nostalgic about the Malice Aforethought Press, Mr Key’s early adventure in small press publishing. Now I have recalled, out of the blue, that back in the benighted 1970s, when I was but a teenperson, I embarked on a similar, even more amateurish, project. I do not know what has suddenly brought this to mind, but I thought it might be of some passing interest to the fanatical devotees among you lot.

‘Twas in the year 1978 that I turned my attentions to what at the time I thought was “proper writing”. The first fruit of this was a piece called Jonathan Owl-Catcher, which as far as I recall was based on an original idea, as they say, by my pal Carlos Ortega. In the interests of clarity I should point out that this was not the Venezuelan union and political leader of the same name, nor any relation to Daniel Ortega, the President of Nicaragua. Having mentioned the title, I must now confess that I remember nothing else about this story whatsoever.

It was with the second piece written at this time that I had the bright idea of publication. Remember these were the heady days of punk and the DIY aesthetic pioneered by the splendid Desperate Bicycles. Having written Uncle Harold Swats At A Moth With A Broom-Handle And Lives To Tell The Tale, what I ought to have done was (a) said to myself “Lord God Almighty, that is an unwieldy and awful title”, and (b) torn it to shreds and stuffed the shreds into a burning fiery furnace.

Instead, I somehow convinced myself that there was a market for this juvenilia, and I proceeded to storm it. My storming was distinctly ill-conceived and inept. I did not even bother to make the story into a pamphlet. I simply photocopied it and fixed the four or five pages together with a staple in the top left corner. At least it was typewritten rather than done by hand.

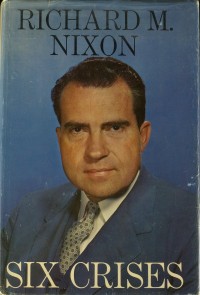

I now had to sell the thing, so I decided to place an advertisement. There was at the time a monthly magazine called Vole, an early organ of the ecowanker tendency. Actually it was a far better publication than that makes it sound, edited as it was by the late Richard Boston. Boston was a Grauniad journalist whose writing was both witty and learned. His 1976 book about the British pub, Beer And Skittles, was a sort of Bible for my elder brother, and I shall always remember a newspaper piece he wrote about the prep school teacher recruitment agency Gabbitas & Thring. Until I read that, I thought the pair had sprung fully-formed from the mind of Ronald Searle.

I was a keen if naïve reader of Vole, so I reasoned that all its other readers would be deeply fascinated by my fiction. Accordingly, I placed an ad in the classifieds, offering my story for sale by mail order. As I had to pay by wordage, and the title was so wretchedly long, I think the entire text of the ad amounted to little more than the title, followed by “short story”, followed by my name and postal address. Yes, children, that was the kind of thing we did in the days before Het Internet.

Remarkably, it seems to me now, I received about five replies. One of these people even wrote back, offering words of encouragement. I wish I could remember his name. He was, now I think of it, the first person outside my immediate family and friends, who ever read a word of mine. Good God! He might even be reading this, now! If so, please get in touch. On the other hand, given the passage of time, it might be a case of R.I.P. Nameless or not, ye shall be remembered.

Duly encouraged, I bashed out another story, The Bassoon Recital. I used the proceeds from my five sales to pay for an advert, again in Vole, for this new piece. (I think – I hope – I sent my mentor a free copy.) It was less successful than the first, selling perhaps two, or it might have been three. But fewer, fewer.

Interestingly, no alternative approach occurred to me. As I am sure you are shouting, I could have, for example, waited until I had written a handful of pieces and cobbled them into a proper pamphlet. Or I could have submitted them to magazines. And if I must insist on trying to sell stapled sheets of A4 to punters, I could at least have advertised them elsewhere. But no. By the time I wrote the last piece, On The Quayside, I had become discouraged, and I do not recall advertising it at all.

So what became of them, these masterworks? It is possible, if I rummaged sufficiently, that I might find a yellowing dog-eared copy mouldering at the bottom of a cardboard box in a cupboard. I may indeed make such a rummage. In the meantime, I will tell you what I remember.

The “plot”, if we can dignify it with that word, of Uncle Harold Swats At A Moth With A Broom-Handle And Lives To Tell The Tale is given in the title. I don’t think anything else actually happens.

The Bassoon Recital would be more interesting, influenced as it was by Edward Gorey. Unfortunately that is about all I can recall.

Of the three, I think On The Quayside is the one I would be least embarrassed to post here at Hooting Yard, were I to fall upon it while rummaging. I remember that the text was deliberately laid out so each paragraph consisted of a single sentence. I remember that the tale involved a crate being hoisted off a ship on to a quayside, and a stevedore taking charge of it, and discovering that within the crate was a demented ostrich. I think the whole thing took place in what we might call Hooting Yardy weather, that is, rain, mist, gales.

And after that, silence, until a few years later, when the Malice Aforethought Press was brought howling into the world, and the first vague outlines of Hooting Yard could be discerned.