Important Hooting Yard postages are unlikely to appear over the following week while I become a temporary member of the international jet-set. During this period, the best thing you lot can do by way of coping is to sprawl in a ditch and sob your little hearts out. To assist you in this endeavour, here is a snap of the sort of ditch in which you ought to sprawl.

Monthly Archives: February 2013

Dispensing Irrelevance

As somebody who refuses to carry a mobile phone, I found myself nodding in agreement with this passage from Simon Raven’s memoir Boys Will Be Boys. He was writing half a century ago, in 1963, about what we now call old-fashioned “landlines”, but how right – and prescient – he was:

Cheap and easy systems of communication simply promote cheapness in what is communicated. If people have to pay 5/- for a telegram or take the trouble to write and post a letter, they think twice before they bother you at all. If they have a telephone, however, even the most trivial information takes on urgency. The telephone dispenses irrelevance like a tap which won’t turn off; it is also a dangerous instrument of interference and even persecution; but like most other so-called amenities of modern life, the telephone is essential for dealing with complexities which the telephone itself has caused, and it is quick to assert its tyranny at the expense of those who, like myself, would ignore it.

Behind The Scenes

Hedger And Ditcher Redux

My father’s a hedger and ditcher. My mother does nothing but spin. And as for me, well, I wallow in sin. At least, I would so wallow, were there any opportunities for sin in this godawful rustic backwater. Oh, how I would like to be a lascivious urban voluptuary, fat and greasy! Instead, I have to spend my days surrounded by straw and hay and pigs – pigs unnumbered! – and my nights tossing and turning on a pallet in a hayloft, exhausted yet sleepless, janglebrained and hopeless.

Sometimes I pore over maps, searching for a path or lane that might lead from this hellhole to a City of Sin. If ever I find one, I shall stuff a few sorry provisions into a hanky and tie it to the end of a stick and tote the stick over my shoulder and set off, one crack of dawn, to march along that path or lane towards my fat and disgusting destiny.

Yesterday the village priest came shambling past the pig sty and I hailed him. I asked him to hear my confession. We went into a secluded corner of a barn.

“Bless me father,” I said, “Though I have not sinned, much as I would wish to.”

“Then you are a pure and holy person, perhaps even a saint!” he replied.

“But what of my sinful thoughts?” I asked.

“Thoughts?,” he said, “You are a peasant, and the child of peasants. Surely you cannot claim to have an inner life? Are you not empty-headed, more akin to a beast of the field?”

“But I do have thoughts,” I protested.

At this the priest looked vexed and troubled. He told me that, if I did indeed have thoughts within my head, I must be a very peculiar peasant indeed. He posited that I might be a changeling.

“I shall have to question your ma and pa very closely, my child,” he said, “And get them to recollect the precise circumstances of your birth. It may be that they found you, bundled up in swaddling cloth, the abandoned babe of a wicked sophisticated urban person.”

“Gosh!” I said.

And thus it was that, later, the priest took me by the hand and led me away from the straw and the hay and the numerous pigs, away along a lane that led to a city. He did not allow me time to gather a few meagre provisions and bundle them up in a hanky and tie the hanky to a stick.

And so I was delivered to the city with nothing but the peasant rags I was dressed in and a letter of introduction to a morally bankrupt urban fop of the priest’s acquaintance.

After I waved goodbye to the priest, I made my way through streets teeming with sin to the fop’s bijou flatlet in a high-rise apartment. He was leaning against a mantelpiece with a glass of brandy in one hand and a book of evil poetry in the other. My heart was thumping. I realised this was the life I had been born to. The foppery, the bijou high-rise flatlet, the brandy, the evil poetry . . .

“You smell of pig,” said the fop, “Begone!”

“B-b-but what of social mobility?” I wailed, “If I have a bath . . .”

The fop held up a dainty hand to hush me.

“Cease your barbaric grunting,” he said, “You speak of phantasms.”

And from behind an arras his valet appeared and dragged me out of the flatlet into the lift, which sank, oh so rapidly!, back down to the street.

Later, sprawled in the gutter, drenched by city rainfall, spat upon by passing urban sophisticates, smelling of pig, weeping, when it seemed all hope was lost, I had a brainstorm, such as occurs perhaps but once in a lifetime. The idea sparked in my head fully-formed, clear in all its details, as sharp and glittering as a diamond. I had discovered the Blairite Third Way!

Explosive Revelations Of Malfeasance, Perfidy, And Pelf

The Appointed Pointy Panel of the Pointy Town Institute of Pointiness was rocked to its foundations yesterday by explosive revelations of malfeasance, perfidy, and pelf. Unnamed sources suggested that the entire edifice could be brought crashing to the ground.

“Let there be no mistake,” said the source, “There has been malfeasance at the highest levels, as well as perfidy and pelf, and not only at the highest levels but at several lower strata. Quite how we go forward following these explosive revelations is unclear. But go forward we shall, pointedly.”

The revelations first threatened to become combustible shortly after breakfast time, and exploded immediately thereafter. So explosive were the explosions that trees, including planes, poplars, pines, larches, sycamores, and yews were flattened, and birds dropped dead from the sky. An eerie orangey purply yellowish mist o’erspread Pointy Town, rendering most of the pointiest bits barely visible.

“I have not seen anything like this since that business of the illegal picnicking hoo-hah of yore,” said one old-timer, a grizzled stoaty fellow leaning against a wall in a pointy part of town. So ancient was he that nobody else had a clue what he was talking about.

Other Pointy Towners were more, or less, circumspect. Some were not circumspect at all. Several had difficulty grasping the concept of circumspection, and of pointiness, and even of malfeasance and perfidy and pelf.

“Personally I can’t see what all the fuss is about,” said a man who gave his name as Unanugu, standing hopelessly at a decommissioned bus stop, “I am just waiting for the 666, even though the little dwarvish familiar perched on my shoulder, invisible to all but me, tells me it will never pass this way again. But if I believed everything it told me I would not be a salt of the earth citizen of Pointy Town, would I?”

Markets reacted in juddering fashion to the explosive revelations. The pane dropped precipitously, then sprang back up, and kept on springing, until it settled, just before dusk, at parity with the grebe.

Emergency coat hangers and tea strainers have been drafted in. The entrails of a slaughtered albino hen will be read today at midday by a haruspex with a klaxon on a balcony in a thunderstorm.

Sparky Plover

I was out one day observing birds when I saw what I considered to be a particularly sparky little plover. I said as much to my walking companion, Dulcie The Bird Woman.

“Look, Dulcie!” I said, pointing, “Is that not a sparky plover?” I pronounced plover to rhyme with the plant, clover.

“I think you will find,” hissed Dulcie The Bird Woman, whose every utterance was a hiss, “That it is pronounced plover to rhyme with the trade of glover, a man who maketh gloves. But be that as it may, what could possibly lead you to dub it sparky? It is not shooting forth sparks, and if it were, I think the both of us would be mightily disconcerted.”

“I was using the word sparky as Father Hopkins deployed it in his juvenile verse drama Floris In Italy,” I said, “Where he writes Such spiders web he ties across his sight, insert ellipsis, Gilds with some sparky fancies blinding night, where sparky is a synonym for lively or vivacious. It is in the same sense it was used as the name of a weekly children’s comic I used occasionally to read when I was a tot.”

“A different sense, then, to the spark translated from the Russian Iskra, which was no children’s comic but an organ of Bolshevik propaganda in pre-revolutionary Russia,” hissed Dulcie, who was surprisingly erudite in many matters not relating directly to birds.

“I wouldn’t know about that,” I said, “I am woefully ignorant of Bolshevism.”

We were standing, having paused to take in the plover, on a path winding alongside an estuary. Scattered here and there beside the path were the stumps of unknown trees. Dulcie The Bird Woman sat down on one, and took from her bag a greaseproof paper package containing a sandwich.

“Of course,” she hissed, between munches, “A robot plover might emit sparks, had something gone awry with its wiring. But only a fool would build such a robot.”

I nodded. I had not brought any sandwiches with me, for I was feckless.

“I have to say,” continued Dulcie, “That your plover seems neither more nor less lively and vivacious than any other plover, nor indeed than any other wading bird. It is merely going about its business in the shallows at the edge of the estuary.”

“It is not my plover,” I protested.

She fixed me with an odd, somehow menacing, look, as she swallowed the last of her sandwich.

“Are you quite sure of that?” she hissed.

“It is merely a plover I spotted and described as sparky,” I said, “Why would I lay any further claim to it?”

Dulcie The Bird Woman chuckled to herself, then hissed:

“It was said, of both Rudolf Steiner and Chou En-lai, that they seemed to emit flashes of mysterious light. Perhaps your sparky plover, too, is such a marvel. Look!”

I was already looking at the plover, and sure enough, it suddenly cast forth a flash of glittering effulgence, a brilliant radiance that would have blinded me had I not turned my head away and shut my eyes. When I opened them again, I saw that Dulcie had put on a pair of sunglasses and was eating a plum.

“That is a very interesting bird,” she hissed, “You were right to point it out, it alone, among all the other plovers and dotterels and wading birds. Here, take this net, and bag your sparky plover, and take it home with you. It will not resist. It is your bird-familiar.”

I had no idea what she was talking about, but, as if in a dream, I took the net she had drawn out of her pippy bag, and I scampered off toward the shoreline, toward the plover. Was it really mine? Was it really my familiar?

As I closed upon it, fanning out the net, it again shot forth a flash of incandescent light, and in that moment it seemed I and the bird and the light were all one. Was it a moment, or was it a year, a century, a millennium? I could not tell. But when the light faded, I dug my short stubby bill into the sand and pulled out a juicy worm, and as I guzzled it down I looked up and saw, sitting on the stump of an unknown tree, a woman. She stood up, hoisted a bag over her shoulder, and, before walking away, she chucked a plumstone at me. It missed me by a whisker.

Wrecks

Before making your choice, you may wish to familiarise yourself fully with each wreck. Click on the links for Thomas de Quincey, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Father Gerard Manley Hopkins S.J.

Buckle! Kindled

You lot are aware, I think, that Hooting Yard is a with-it, groovy, space age kinda place. If proof were needed (which it isn’t) then what could be more with-it and groovy and space age than the release of Mr Key’s recent paperback Brute Beauty And Valour And Act, Oh, Air, Pride, Plume, Here Buckle! in the decisively intangible form of an ebook for Kindle?

Go here and make your purchases, oh electronic persons!

No Actual Mention Of Dick Van Dyke

A very pleasing cryptic crossword in the Grauniad yesterday, where clues yielded the words SOUP, a COLLIE, FRIDGE, ELASTIC, EGGS, PEAS, HALITOSIS and MARY POPPINS.

Hedger And Ditcher

One of my uncles was a hedger who had his own ditch, and another uncle was a ditcher who laid claim to a hedge. That’s the thing about being a peasant, it can be mightily confusing. When I was a tot I always used to get the hedger uncle and the ditcher uncle mixed up. Their brother – my father – tried to teach me which was which, though his pedagogical methods were rather unusual. He seemed to believe I might learn to tell a hedger from a ditcher by penning me in a pig sty among the many pigs from dawn till dusk, with slate and chalk, and a sort of metal harness on my head, a contraption he had beaten out of a broken churn.

My father, you see, unlike his brothers, was a peasant with ideas. Few if any of them were sensible ideas, nor were any of them the fruits of rustic wisdom, handed down through the ages. No, my father’s ideas sprang fully-formed into his head. It was an odd head, a bit too large for his body, plum-coloured, and topped with an extravagant bouffant that might better have suited a maestro of the opera house. Somebody had once told my father that his head had to be a bit too big in order to contain comfortably his gigantic brain. That they were joshing him never occurred to Papa. He really believed, in the absence of any X-rays or probes or scans, that he had an enormous, and concomitantly powerful, brain.

When he died I took it upon myself to remove the brain from his skull, using a saw, and I discovered it to be no bigger than the average adult human brain. If anything, it veered towards the smaller size. I put it in a jar filled to the brim with brine, screwed the cap on tight, and then released his body to the priest for burial, but not before gluing the top of his head back on to conceal evidence of my unauthorised sawing.

He was the first of the brothers to go, so when I held a little wake, after the funeral, both my uncles, the hedger with the ditch and the ditcher with the hedge, were present. They were leaning against the pig sty fence, glugging grog from tin beakers, and muttering to each other in their guttural barbaric peasant argot. It made no sense to me, as one of my father’s mad ideas had been to bring me up to speak as if I were a person of consequence in the world. Thus my speaking voice, in addition to my slate and chalk and my metal head-harness, marked me out from my fellows and made of me something of an oddball.

Now that Papa was dead I felt I should get to know my uncles better, or at least well enough to tell the one from the other. I thought they might be interested to see the brain in the jar, so I took it from the shelf in the barn where I kept it and approached them at the pig sty fence.

“Hello, uncles,” I piped up, in my hi-falutin voice, “Look what I’ve got here!”

They turned, the hedger and the ditcher, from gazing at the pigs to gazing at me. In their eyes I saw thousands of years of stupidity and rustic ignorance, and at once I knew I would never be able to make myself understood to them. The hedger, or possibly the ditcher, grunted, and the other belched.

“This is Papa’s brain,” I said, waving the jar in front of them, “You see, it was not so huge after all.”

Then they both spat into their beakers, and each mussed my hair, or as much of it as they could muss through the metal harness, and they trudged away, the one to his hedge or ditch and the other to his ditch or hedge.

Oh, it was all so long ago. I think of them now, my uncles, as I slump at my desk in my ivory tower, surrounded by fat dusty books in incomprehensible languages, and up there, on a high shelf, sits the jar of brine containing my father’s brain. It has shrivelled over the years, until it is a tiny thing, a tiny thing indeed.

NOTE : I suddenly recall that I wrote an earlier piece with the title Hedger And Ditcher, which is also preoccupied with my father. It is worth noting that the fathers in both pieces are wholly fictional, and if they bear any resemblance to my real father at all, it is a lopsided resemblance born in my brain.

A Wednesday In Split

One Wednesday afternoon in Split, Ferdy Pogóstic was bouncing along the boulevard on his pogo-stick when he heard a voice in his head.

“Ferdinand! You are the living embodiment of the great Gak! Go forth and do the doings of the Gak!”

But Ferdy heeded not the voice, and continued to bounce along. So the voice returned, more insistent, deafening, until Ferdy paid attention to it. He stopped bouncing, and chucked his pogo-stick into a canal, and went forth as instructed.

His first stopping point was a Split butcher’s shop. He marched in under the awning and announced to the startled butcher that he, Ferdy, was the great Gak, and that he must have a blood sausage.

“For the great Gak has a blood sausage in all the paintings and icons,” he added, as if in explanation.

The startled butcher had no idea what this bedraggled fool was talking about, and sent him packing with a flea in his ear.

And so Ferdy Pogóstic went a-wandering through the streets of Split, without his pogo-stick and without a blood sausage, and nobody recognised him as the living embodiment of the great Gak.

And eventually, on the outskirts of Split, he sat him down anent a well. And then came the voice once more within his head.

“Oops. I mistook you for a different bedgraggled fool. You are not after all the living embodiment of the great Gak. My apologies.”

And Ferdy Pogóstic sat by the well and wept.

And there came a terrific thunderstorm and teeming rainfall, so much rain that the well filled up with water, until it overflowed. And there, bobbing to the surface, was a well-duck, with bright feathers and gleaming beak. It quacked at Ferdy in a language he did not comprehend. He chucked a pebble at it.

By now it was Wednesday evening and time for Ferdy to go home. In spite of the unfriendly pebble, the duck splashed out of the well and followed him, waddling in his wake. And when he was home and was sitting in his armchair by the fire in his chalet in an insalubrious neighbourhood in Split, the well-duck came and sat upon his head, and would not budge.

“Tomorrow,” said Ferdy to himself, “I must retrieve my pogo-stick from the canal. Perhaps when I am once again bouncing along the boulevard I will be able to dislodge this damnable duck.”

But could he?

Across town, the startled butcher was in the back room of his shop, behind a bead curtain, stuffing sausage skins with the blood of ducks. On the wall hung an icon of the great Gak. Or was it the butcher’s mirror?

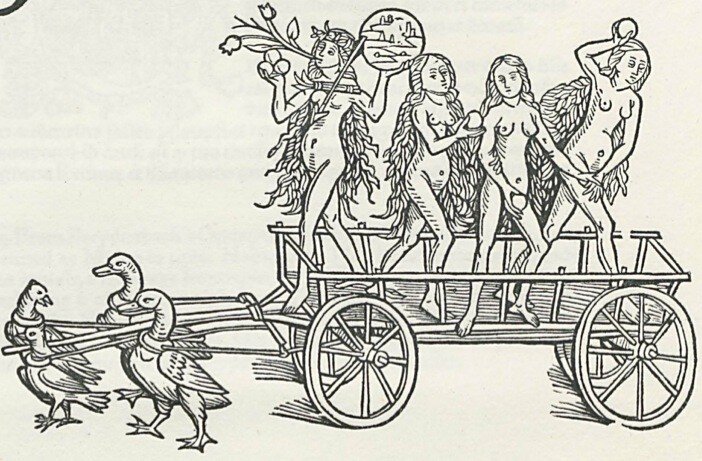

Venus Chariot

I am indebted to Richard Carter for drawing to my attention this woodcut he came across on Twitter, where it was given the caption “just a bunch of fruit-wielding naked women riding a duck-driven cart”.

R.I.P.

Marginal Notes And Poetic Mirrors

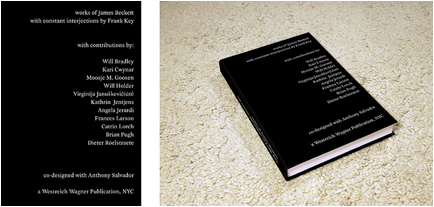

I mentioned recently that in the first week of March I shall be rejoining the international jetset and swooping down upon New York City. This kind of shenanigans undermines my reputation as a Diogenesian recluse, but you will be relieved to hear that I am bent upon important Hooting Yard business. To wit, the launch of this lavish and lovely book:

Here is part of the official press release from Westreich Wagner:

“works of James Beckett with constant interjections by Frank Key”

In a spatially and conceptually complex arrangement of text, image and scale, this book is a multi-vocal account of the varied practice of Amsterdam-based artist James Beckett. Beckett’s work explores minor histories, many of which are concerned with industrial development and demise across Europe, a process of investigation which is as much physical as it is biographical. The pages of this new monograph are littered with associative interjections from the archive of Frank Key’s radio program “Hooting Yard”, as an irreverent running commentary. These texts become marginal notes to, and poetic mirrors of, the contributions of the book’s eleven other authors.

Contributing Authors:

Will Bradley, Kari Cwynar, Moosje M. Goosen, Will Holder, Virginija Januškevičiūtė, Kathrin Jentjens, Angela Jerardi, Frank Key, Frances Larson, Catrin Lorch, Brian Pugh and Dieter Roelstraete.

The launch itself, which will feature Mr Key spouting his texts out loud, takes place from 6.00-8.00 PM on Monday 4 March at 114 Greene Street, Floor 2, New York, NY 10012. Should any fanatically devoted Hooting Yard readers and listeners wish to attend, please send a note to the publishers here.