For reasons which I cannot fathom, I feel impelled to repost this potsage [sic] stamp design, depicting men with whisks and celery.

Monthly Archives: March 2014

Thatcher Bird Comparison Update

When Margaret Thatcher died last year, I devoted one of my potsages [sic] for The Dabbler to the unresolved question of which bird she most closely resembled. I noted that Matthew Parris claimed “she walked like a partridge”, while Jon Snow asserted “she scuttled about like a hen”. Now things have become more complicated. Reading Dominic Sandbrook’s Seasons In The Sun : The Battle For Britain 1974-1979, I learn that the Daily Express compared the then-future Prime Minister to “an angry woodpecker”.

The New Motive Power

The New Motive Power was constructed of copper, zinc and magnets, all carefully machined, as well as a dining room table. At the end of nine months, Spear and an unnamed woman, also referred to as “Mary of the New Dispensation” ritualistically birthed the contraption in an attempt to give it life. Unfortunately for Spear, this failed to have the desired effect, and the machine was later dismantled.

The sort of paragraph that compels me to do further research. From John Murray Spear & The Electric Messiah in today’s Dabbler.

Nisbet Dabbling

This week in The Dabbler, my cupboard contains a reminiscence of my childhood devotion to nisbet spotting. I have been thinking of taking up the hobby again.

Near And Middle And Far

I remember as if it were yesterday my very first encounter with Tarleton. He was propping up the bar in a beige and dismal drinking den, beetle-browed and lantern-jawed and babbling to no one in particular. I sat on a stool beside him, ordered a sprangeloenkenkischt, and listened to what he had to say.

He was only recently back from a hush-hush mission in the East, and was worrying, like a dog with a sheep, at the impossibility of grasping the difference between the Near East, the Middle East, and the Far East. What seemed to bother him was that, whereas the location of the Middle East was as clear as dammit, between the Near and the Far, placing the Near and the Far was by no means as simple a matter. If you were slap bang in the middle of the Middle East, for example, the Near East and the Far East would be equidistant from where you stood, or sat, or lay sprawled in a hammock in the blistering noonday sun, going mad.

When he briefly paused to glug his kolokkengehemmelbe, I asked him which East, Near or Middle or Far, he had been in, on his hush-hush mission. Swallowing the dregs of the fiery liqueur, he spluttered and told me the point of a hush-hush mission was that it was hush-hush. I could not disagree with that. I bought him another drink. His tongue did not need loosening, but I was at a loose end, and he seemed to be a man of parts, well worth listening to.

I was wrong. For the next two hours, he gabbled on and on and on, without cease, trying but failing to settle the matter of the three Easts, Near and Middle and Far, now and then pulling from his pocket a crumpled map, hand-drawn with a leaky biro on a filthy napkin, on which he had tried, tried and failed, tried again and failed again, like the best or worst of Beckettians, to hammer home the geography of the East, to pin it down, definitively, so that he would no longer need to think about it. That, he said, in among his witterings, was what he could not stand – that no matter how hard he tried, the East would remain forever beyond his grasp.

Eventually he staggered off to the lavatory to vomit. He had left the napkin map on the counter. Idly, I picked it up. I turned it this way and that, and then, feeling the breath of God on the back of my neck, I crumpled it up and uncrumpled it and turned it upside down and back to front. I laid it back on the counter and smoothed it out, downed the last of my goospelkschnittzern, wrapped my muffler tight about my neck, and tottered out into the icy blizzard. As I followed the tractor-tracks back towards my chalet, I heard from inside the bar a scream, at once hysterical and tragic and unhinged and ecstatic. I lit my pipe, as snowflakes fell.

The Rubbish Dump

Note well the co-ordinates of the rubbish dump. Lit lantern, hand-held, visibility Stygian. Pebbles underfoot. Buck collar snug at the neck. Distant incomprehensible keening. The mighty pyramids of Ancient Egypt. Satyrs cavort in the forest. A galumphing peasant with a pail. The rubbish dump would appear to be not far from the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Crows fly there, on the hour, timetabled. Clack clack clack, rapid clacks. That kind of timetable. Rain on the pebbles. An orphan choir sings a song.

Bob Crow, Bob Crow

Made out of dough

Eat him up with salt and herring

A biff in the chops from an unknown assailant. Fleeing in the gutter. On All Hallows Eve, pictures of Jap girls in synthesis. The seven wonders of another world. Resurrectionists scurry in the night. Spades at the ready. Bob Crow, Bob Crow.

Sibelius was a terrible drunkard. A dog sniffing a ditch. Frisky terrier, lumbering hound. Two dogs then. The Colossus of Rhodes. Young marble giants. Wind in the rigging. A frump with a towel in a doorway, like Harry Lime in postwar Vienna. Wheels within wheels. The windmills of someone else’s mind. Mind how you go, sir. There’s room for one more inside.

There’s room for one more skip at the rubbish dump. Babylon or Chartres. Sing, sing, in a cathedral choir. Nunc dimittis. And he had received an answer from the Holy Ghost, that he should not see death, before he had seen the Christ of the Lord. Bob Sparrow, Bob Lark.

Rain in the gutters and filth on the stairs. I hear the sound of mandolins. Now the orphans sing.

Bob Crow, Bob Lark, Bob Bobolink

Call for another round of drinks

We are teetering on the brink

Let’s fall into the abyss.

Visibility nil, in the abyss. Can I get a witness? Is there honey? Is there tea? No. You have drained your cup. You could not make it up.

A new ghost.

Oh Prunella!

Oh Prunella! Thou art fair! But is it true that thou has lost thy marbles? Just now I was engaged in breezy chitchat with old Greavish the retainer, by the filbert hedge, and he said you had taken to hiding behind the arras waving a new-darned sock from your dainty hand, to and fro, to and fro, while humming a bawdy song. That is why I came bounding across the lawn past the box hedge and the serried rows of owl traps, and dashed into the house and up the stairs to your boudoir, to find out if Greavish spoke the truth. And now I find you here, so fair, not behind the arras at all, but slumped on a divan, toying with pickles in a jar, and by your slipper-shod feet another jar, sealed, in which there appears to be a creature of the sea, enbrined, globular, and luminous. The sock you were wafting has been tossed aside against the wainscot, where it is being gnawed by a little mouse. Thou art not singing, now, but keening, a low, melancholy keening, redolent of untold centuries of historic wrongs unrighted. I shall bring you a flan from the pantry, oh my Prunella! And then I shall lift you to your feet and carry you all the way to the house of Dr Slop. It is an untidy house, dilapidated and falling down, but within the good doctor maintains a laboratory in which he conducts his brain sluicing experiments. I shall pay him a few sous and hand you over to his care until springtime. Come, Prunella dear. Let drop your pickle jar. Think no more about the sock. I will take your sea creature to the aquarium as soon as I have you safely installed with the doctor. Do not, oh! do not scamper behind the arras where I cannot reach you. Sing not that bawdy song! It assails my ears and I must stuff them with cotton wool. Greavish! Greavish! Come quick! The sea creature has broken the seal upon its jar and is slithering across the rug towards the arras! Oh God in heaven. Glubb … glubb … glubb …

Fab!

Reading about yet another teenage shooting murder in east London in yesterday’s paper, I could not help but burst into inappropriate laughter at the name of the victim. Her name, apparently, was Shereka Fab-Ann Marsh. “Shereka” is bad enough, eliding easily into “Shrieker”, but “Fab-Ann”? What on earth were her parents thinking?

I am not sure if it is possible for me to re-register the births of my own (now adult) sons, but I am tempted to rechristen them Fab-Sam and Fab-Ed. And while we are about it, could I become Fab-Frank? Or perhaps With-It-Mr-Key?

Perhaps the tragic Miss Marsh’s parents were fans of Thunderbirds.

Grotto Cad

You don’t expect to find a cad in a grotto. But that is exactly what I discovered during a spot of seaside spelunking many years ago. I had abseiled down a cliff, having been told by my colleague Dennis Pivot that there was, at its foot, partly submerged under water, a grotto which, he thought, was the portal to a magnificent and extensive system of caves never before explored.

“What makes you think that, Dennis?” I had asked him, as we ate sausages in a seaside cafeteria.

“Clues strewn in various rare manuscripts of olden times,” he said. When I pressed him for further details, he pretended to be chewing on a piece of gristle, then gagged, spat into a napkin, and keeled over. It was a convincing performance, and at the time I had absolutely no idea he was dissembling.

I hired some kit and headed for the cliff. It was a squally day. Gulls were screaming their heads off. My ears are oversensitive to certain bird shrieks, so I stuffed them with cotton wool. Then I abseiled like the abseiling expert I am down the cliff face. What with the cotton wool and my cushioned helmet I couldn’t hear a thing. At the bottom of the cliff, I swung myself into the grotto. I unfastened myself from my abseiling rope and stood for a moment or two, knee deep in sloshing seawater, to catch my breath. That is when I saw the cad.

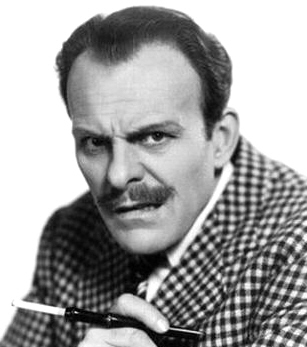

He came looming out of the Platonic shadows at the back of the grotto, a dapper fellow in spite of the cheapness of his suit. Like many a postwar cad, he bore a striking resemblance to the actor Terry-Thomas (1911-1990).

“Hello old chap!” he said, “I say, you couldn’t see your way to loaning me a few bob, could you? Had a run of bad luck on the old gee-gees, you know how it is.”

I couldn’t hear a word he said, and gestured to indicate as much. Then I took off my helmet and prised the cotton wool out of my ears and asked him to repeat himself. After he had done so, I explained that I never carried cash when abseiling, for fear it might fall from my pocket into the merciless sea.

“Drat!”, he said, and then offered to place some bets for me if I met up with him at Waterloo Station on the following Thursday and forwarded him several hundred pounds.

I promised to think about it, though in truth my puritanical ways made it very unlikely that I would ever get embroiled in any form of gambling.

“Tell me something,” I said, “You seem to be familiar with this grotto. I’ve been led to believe it leads to a magnificent and extensive system of caves never before explored. Is that indeed the case?”

“I haven’t got the foggiest,” he said, “Only been here a couple of weeks, haven’t quite got my bearings.”

This surprised me. I had always thought it a characteristic of cads that they were quick to grasp the possibilities of whatever circumstances they found themselves in. I put this to him, without actually calling him a cad. By way of reply, he changed the subject.

“I say, you couldn’t loan me those bits of cotton wool, could you? I’m being driven crackers by the shrieking of those damnable gulls.”

I was reluctant to relinquish my makeshift earmuffs, and told him so. I still cannot remember how he managed to wheedle them out of me, nor how he convinced me to let him try on my abseiling harness, which, having donned, he attached to the rope dangling at the grotto’s opening, whereupon he rapidly ascended, leaving me alone. The sloshing seawater was now up to my waist.

There was nothing for it but to make my way deeper into the grotto, in the hope of discovering a magnificent and extensive system of caves never before explored. But was my colleague Dennis Pivot right, or was he talking twaddle, as he so often did?

On this occasion, I am relieved to report, he was bang on the money. I spent several days clambering about underground, the first man to see, oh!, such wonders!

But when Thursday came I determined to find my way back to the grotto and then, somehow, up the cliff face. I remembered I had an appointment to meet the cad at Waterloo Station, and though I had no intention of giving him several hundred pounds to bet on the horses on my behalf, I dearly wanted to retrieve my abseiling harness and rope and cotton wool.

When I got to the grotto, the tide was in, and the sloshing seawater came up to my neck. Without my abseiling gear, I knew I could not hope to scale the cliff, so I decided to plunge ahead and make a swim for it. There was a terrible risk that I would be dashed to pieces on the rocks. Luckily, I managed, by dint of advanced swimming techniques, to steer my way through the tremendous currents, and by midday I was panting on a shingle beach. I was exhausted and sodden and had numerous tiny crustacean beings snagged in my hair, but I was alive.

Stopping only for a reviving cuppa in a seaside cafeteria, I caught a train to Waterloo Station. And there, on the concourse, waiting for me, I spotted the cad. I squelched towards him.

“There you are, old bean,” he said, “Have you got a wodge of the folding stuff?”

“No I have not!” I cried, “I am of puritanical bent and I never bet on the horses. I have come for my abseiling harness and rope and my cotton wool, with which I entrusted you in the grotto.”

“Of course, old boy, of course,” he said, a gleam of mischief in his eyes, “I put them in a locker for safe keeping. Here – “ and he handed me a key – “Number 666. Be seeing you!” And he scarpered.

I asked a railway person where the lockers were, and went straight to them. I inserted the key into the lock of locker number 666, and opened it. There was no sign of my harness, my rope, and my cotton wool. Instead, what I found in the locker was the thing that, had I but known, I would have dropped as surely as one drops a burning potato, for it led to my utter ruin in this world, and my damnation in the world to come.

Terry-Thomas, for younger readers who may not know what a postwar cad looked like

A Preposterous Hovercraft Tour

Jeremy Thorpe spent the early weeks of the [October 1974 general election] campaign on a preposterous hovercraft tour of English seaside resorts, providing broadcasters with plenty of pictures of himself “struggling ashore in bedraggled oilskins” while aides toiled miserably to restart his unreliable vehicle.

Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons In The Sun : The Battle For Britain 1974-1979 (Allen Lane 2012)

Cnidaria Medusozoa Bulletin

Thanks to Outa_Spaceman for drawing this to my attention

Crank’s Bumf

Experience tells us that most cranks hoick their bumf about in carrier bags. Any crank’s bumf will be peculiar to his own idée fixe, whether it be UFOs, the second coming of Christ, the grassy knoll, or one of any number of tomfooleries. But no matter what the precise nature of the mania, the crank almost invariably stuffs his bumf into a carrier bag before setting out into the world.

Having so set out, he makes his way to his preferred spot. This may be, for example, at the foot of a statue in an important square. There will be many passers-by, weather permitting, each and every one of whom is a potential convert to the crank’s cause. Bumf in bag, he may either rant through a loudhailer or, more quietly, buttonhole individuals by thrusting a sample of his bumf at them as they pass.

The bumf usually consists of a bundle of Gestetnered screeds, of wild and improbable prose, which the crank will be willing to give away gratis. The carrier bag will contain numerous copies, often dog-eared and crumpled. Most days, the crank will return home with almost as many in his bag as when he set out.

What does he do, the crank, when not at his spot? He scribbles a new and more thorough screed, sitting at his kitchen table. Each day he gains new insights into his inner world, finds fresh evidence for his theory, and he commits it to paper. The best type of crank will have in his bumf several different screeds, all of course devoted to the same subject.

It will be noted the very few cranks ever veer from their chosen topic. A Loch Ness Monster crank is oblivious to the concerns of a Lindbergh Baby Kidnapping crank. But it is also worth noting that, with the substitution of a small number of nouns, the screeds in their bumf can be almost identical.

It is generally impossible to become an ex-crank. The most a crank can hope for is that his mad ideas gain acceptance by the wider world. Then he is no longer a crank but a prophet or a visionary. In the future, in recognition, a statue of him may be cast, and placed on a plinth in an important square. At the foot of the statue, a new crank will take his place, with a carrier bag of bumf, and the gleam of certainty in his wild eyes.

The Demon Of The Air

On 24 December 1892 … [George Albert] Smith announced in the Brighton and Hove Herald that he had taken a lease of the St Ann’s Well pleasure gardens … By April 1893 Smith had been able to “supplement the many natural attractions” of St Ann’s Well by the addition, among other things, of a monkey house, a gypsy fortune teller, swings and see-saws for the children, and by popular lectures and demonstrations by himself.

In May 1894 Smith announced that St Ann’s Well had become one of the most popular amusement resorts in Britain. He claimed that “close to 3,000 visitors” had paid 3d. for admission on Whit Monday. The attractions now included captive baboons, an exhibition of dissolving views “by means of long-range limelight apparatus”, and juggling and trapeze artists.

Smith’s advertisements in the Brighton and Hove Herald and the Brighton Gazette on 7 and 9 June 1894 announced a “BALLOON ASCENT AND THRILLING PARACHUTE DESCENT by Neil Campbell, Australia’s ‘Demon of the Air’”, on the following Saturday, augmented by trapeze, juggling, and balancing acts. “The Demon of the Sky”, it was said, “will perform his wonderful leap from the sky from a height of one mile by means of a parachute.” We may perhaps think that a mile was an exaggeration. However, in the event, Smith created more of a sensation with his “Demon of the Air” than he could have anticipated. “Half of Brighton”, apparently, “was wild with excitement”, because during the ascent of the hot-air balloon the Demon had been unable to free himself to make his spectacular parachute descent. After drifting over the town the balloon, with the Demon still attached, crashed into Brighton cemetery. The Demon, it was stated, broke a tombstone by the force of his descent, but was miraculously uninjured.

[Let us leap forward sixty years…]

When the National Film Theatre was opened on London’s South Bank in 1957, the [British Film] Academy invited the now ninety-three-year-old Smith as a guest. He was presented to Princess Margaret, met Gina Lollobrigida and other stars of the film world, and was given a picture of the theatre by Lord Hailsham.

Trevor H. Hall, The Strange Case of Edmund Gurney (Duckworth 1964)

Bird Index

Keen Hooting Yardist Ruthie Bosch drew to my attention the Stith Thompson Motif Index of Folk Literature, or more precisely the index to that Index. That was a week ago, and I am still trying to reorient my brain to take account of its existence. The world has changed for me, irrevocably. To give some idea of what I am babbling on about, you lot should listen, immediately, with lugholes alert, to today’s episode of Hooting Yard On The Air, in which I took the opportunity to read (most of) the Stith Thompson Index index for Bird.

A Shot In The Dark

There is a story in today’s Grauniad about young Polish artists being recruited to recreate Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings for a film. Young British artists, apparently, lack the skills for the work because all they are “taught” (if that is the word) at art school is how to make conceptual art. That would certainly explain the unbelievably tiresome twaddle exuded by the Hoxtonwankers.

A professor at the Royal College of Art insists “there are some very fine painters, but the focus is on innovation and finding a new way of painting”. Well, fine, but it might help if students learned some “old” ways of painting first. Minor things like how to hold a brush and how to apply paint to canvas – that would be a start.

But that is by the by, because what really got my attention was the final paragraph of the story, referring to the film.

Loving Vincent will question whether Van Gogh’s death was suicide or murder. [Co-producer] Welchman points to a Frenchman’s “oblique” admission that he shot the artist and that police have never found a weapon.

The inference of that last phrase is surely that the French police are still investigating. If it said “police never found a weapon”, that would consign it firmly to the past. The inclusion of “have” suggests a live, ongoing enquiry. The thought of various gendarmes scrabbling around Auvers-sur-Oise and environs searching desperately for a revolver undiscovered for a century and a quarter is most enticing, and could provide the basis for a police procedural crime thriller, though it might be fairly low on thrills.

Authentic photo of Vincent Van Gogh from the Auvers-sur-Oise Gendarmerie Archives