Our alphabet continues with C for canker worm.

Sorely perplexed was I, that I was waking each morning, and had been for months on end, engulfed in a miasma of unutterable spiritual desolation. I sought advice from a quack I encountered on a charabanc outing. He was sitting in the seat next to mine, all wrapped up in a visible aura of wisdom, a sort of pinkish violet haze, and his one good eye seemed, to me, to emit a ray, a ray that could pierce my spiritual innards were he but to train it upon me. I tapped him on the shoulder, so he would turn to face me.

“You look like the kind of fellow who might be able to diagnose the miasma of spiritual desolation within which I tremble, engulfed,” I said, not beating about the bush.

“I am that man,” he replied, and about thirty seconds later he added “You have a canker worm nestling within the very core of your soul, and it is gnawing away at your spiritual vitals.”

“I knew I could rely on you,” I said, possibly a bit too loudly, for elsewhere in the charabanc heads turned and craned to look. I slipped some coinage into the quack’s outstretched palm, settled back in my seat, and shut my eyes. Soon enough we reached the destination of our outing, a ruined fortification of great antiquity and becrumblement, lashed by wind and rain. Tugging my windcheater close about my puny frame, I fairly skipped out of the charabanc into the mud, animated by a sense that, having discovered the cause of my unutterable spiritual desolation, I could now do something about it.

But what was I to do? The canker worm was nestled in my soul, and we still do not know whereabouts within us the soul resides. Indeed, there is a growing body of opinion that we do not have souls at all, that the whole idea is a phantasy, or a metaphor, or just blithering nonsense. Well, I laugh in the face of those who deny the soul’s existence! I may not know precisely where mine is, in brain or heart or spleen or kidney, but I know that it is about the size and shape and colour of a plum tomato. I was told as much by a Magus at a seaside resort, long, long ago.

Traipsing round the ruin, and then on the charabanc journey back – during which there was no sign of the quack, his seat next to mine having been taken by a television chat show host to whom I could not quite put a name, and dare not ask, for he was frowning mightily – I mentally chewed over what I might do about my canker worm. Was there some substance or formula I could ingest that would do me no harm but would blast the little canker worm to perdition? Some potion or preparation, of milk and aniseed and potable gold? Or could I somehow excise it with a pair of ethereal pliers? That might put me at risk of irreversible psychic injury, of course, but was it a price worth paying?

I juggled these and other thoughts until my brain overheated, at which point I went to bed, for it was by now late and dark. While I slept, I had a dream, like Dr King, and when I awoke, I wanted to go and stand on a podium, like Dr King, and declaim the contents of my dream to the gathered masses, declaim it in powerful preacherman language. It took me a few seconds to realise that I had not the magnetic charisma of Dr King to attract the teeming thousands to hear me. The next thought that popped in to my head was to wonder precisely when “Dr King” became the preferred way of referring to the Reverend Martin Luther King, and if this had happened at the same time as it became obligatory for all United States Presidential candidates so to mention “Dr King” in at least one campaign speech, to garner guaranteed applause. Seconds later, the next, and most important thought, occurred to me. For the first time in months, I had woken up without feeling engulfed in a miasma of unutterable spiritual desolation! Quite the contrary. I was filled with vim and gush and pep. I was ready for a large eggy breakfast, and nothing was going to stop me.

Tucking in to my eggs, prepared in accordance with the Blötzmann system (see the appendix to the third handbook in the Lavender Series), I tried to remember my dream, as clearly it provided the clue to my new-found mental and spiritual wellbeing. But I could remember nothing, so after a post-breakfast hike along paths and lanes and canal towpaths, and through a municipal park, I took from its cubby my hat-sized metal cone, plopped it atop my head, aligned my head at the correct angle (see the instructions in Blötzmann’s seventh handbook, Lilac Series) and stared into space, mouth hanging open, dribbling.

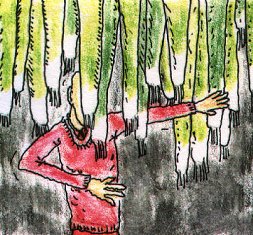

Gosh! It soon became apparent that, in the mists of sleep, I had visualised my little canker worm, gnawing its way through my plum tomato-shaped soul, and instead of seeing it as an invader to be repulsed or expunged, I had cosseted it as a pet. I named it Dagobert, and furnished it with a hutch, and pampered it, and took it for walks, insofar as a worm can walk, attached to a lead. The lead was made of ectoplasmic string from a spirit-viola.

The question now was whether I was able to apply these methods to my real, albeit invisible and intangible, spiritual canker worm. Perhaps, if I kept the metal cone on my head beyond the recommended time-limit, thus risking weird head judderings, paralysis, and death, I might be granted the powers to construct Dagobert’s little hutch. After all, I reasoned – ha, reason! – if he was snug in his hutch he would desist from his gnawing, wouldn’t he? I was certain, though on what grounds I knew not, that my plum tomato soul could regenerate sufficiently to repair all the damage caused by the gnawing. But where would I take my little canker worm on its necessary walks? Under the metal cone, my head grew hot and frazzled, and I fell into a swoon…

The following week, I once again boarded the charabanc for an outing, this time to a den of iniquity preserved in quicklime. I sat down next to a different quack, one whose visible aura was purple and golden, and whose spirit-piercing ray projected, not from his eye, but from a star in the centre of his forehead.

“Excuse me,” I said, “But you look like the kind of fellow who might be able to see into my soul and tell me if it is being gnawed at by a little canker worm named Dagobert.”

“I am that man!” he roared in reply, and aimed his ray at me. I waited for him to report his findings. As I waited, the driver lost control of the charabanc and we veered scree scraw off the road and plunged into a ditch. The ditch was riddled with puddles, and each puddle was rife with worms, and some of them were canker worms, and they were legion, and uncountable. But somehow, I could count them, and I did, and I learned that as we flailed, panting and stricken, in the ditch, their number had increased by one. Little Dagobert had gone to join his fellows in their cankerous ditch-puddle of doom, and I was free!