It is rather quiet at Hooting Yard at the moment. Partly this is because I am recovering from the ague which felled me last week, and partly, I think, because I am reading a stout collection of short stories by M P Shiel. It is two decades since I last immersed myself in the works of that master of purple prose, but I am a sensible person, and, as Rebecca West so wisely said, “Sensible people ought to have a complete set of Shiel”. I do not own such a set, but that may be a small mercy. Reading Shiel may not exactly fuddle the brain, but I must be very careful not to try to imitate his highly-wrought outpourings when tippy-tapping my own prose. Long-time readers may recall what happened to Dobson when he fell under Shiel’s spell…

Category Archives: Dobson

Archival Sludge

J

The OED defines jiggery-pokery as “deceitful or dishonest ‘manipulation’; hocus-pocus, humbug”. By OED, I mean the Oxford English Dictionary of course, the common referent of that abbreviation. The out of print pamphleteer Dobson, however, tried to foist upon the world another OED, the Omni-Encyclopaedia Dobsonia. We must be careful, when ploughing through the works of the pamphleteer, not to mistake one OED for the other. If we look up “jiggery-pokery” in Dobson’s own OED, we are told simply, “see pamphlet”. In fact, pretty much anything we look up in Dobson’s OED carries the same advice or instruction. It is difficult to see the point of this so-called reference work, which consumed many, many hours of the pamphleteer’s time. Even if we consider it as a sort of universal index to the contents of his pamphlets, it is by and large worthless, as he never deigns to inform us which particular pamphlet he is enjoining us to “see”.

In the case of jiggery-pokery, though, we are on firm ground. The pamphlet to which the OEDobsonia refers must be The History, Theory And Practice Of Jiggery-Pokery, From Ancient Times Up To Yesterday Morning, With Practical Tips And Cut Out ‘N’ Keep Cardboard Display Models For Your Mantelpiece (out of print). At barely a dozen pages, the pamphlet is distressingly brief, and nowhere does Dobson grant us a definition, so we are never entirely clear what he means, or understands, by the term “jiggery-pokery”. There is one lengthy paragraph which seeks to describe, in mind-numbing detail, a series of “manipulations”, “passing movements”, “flummeries and gesticulations” and “hoo-hah” which the pamphleteer watched being performed by a man he describes as “a shattered ship’s captain” on board a boat plying an unidentified sound on New Year’s Eve 1949. If we accept this to be a description of jiggery-pokery, we are none the wiser regarding its purpose, as Dobson does not bother to tell us. One suspects he had no idea what he was looking at.

The pamphlet’s title makes great claims, which only the most charitable reader could consider are met. History? Well, Dobson has a couple of sentences in which he makes glancing reference to “well-known instances of jiggery-pokery by Lars Porsena of Clusium and one-eyed Horatius Cocles” and to “that funny business involving a certain Frankish king”, but we are left scratching our heads wondering what on earth he is talking about. I just scratched my head, incidentally, and a beetle fell out of my bouffant. Time to wash my hair with a proprietary shampoo! Wait there.

I have returned, cleaned and preened and ready to proceed. Where were we? Ah yes. If the “history” element of the pamphlet’s title is scarcely justifiable, what about “theory”? On page five, Dobson announces, with quiet menace, “The time has come to consider jiggery-pokery in the abstract”. This is menacing because anybody who has even a passing acquaintance with the pamphleteer’s work knows that when he embarks upon passages of “abstraction” the best thing to do is to bash one’s head repeatedly against a surface of adamantine hardness until one loses consciousness. There was a time, when I was foolishly attempting to write a magazine article entitled “Abstract Dobson”, when I actually installed a rectangular panel of granite next to my writing desk, so I could do the bashing without having to get up from my chair. If you fear your cranium cannot withstand repeated bashing, it is important to find an alternative method of dealing with the all too potent horrors of Dobson in “abstract” mode. Some illegal pharmacists with pharmacies tucked away down sordid alleyways may be able to procure for you the kinds of powdered tranquilisers that can stun an entire herd of cattle, but ingesting them, even in a bergamot-scented tisane, has its own risks. Some more experienced Dobsonists have tried the trick of simply flipping past the awful pages and resuming their reading when the pamphleteer gets some sense back in his head. Do what you have to do.

For now, all I will say about Dobson’s “Theory of Jiggery-Pokery” is… glubb… glubb…glubb-glubb. Some of you will recognise that as the telephone call made by a terrifying semi-aquatic creature in The Thing On The Doorstep by H P Lovecraft. Warning enough, I think.

And so we come to “Practice”, which I suppose Dobson addresses in that interminable paragraph about the shattered ship’s captain, but as we have seen, whether what he witnessed was jiggery-pokery, or some kind of maritime ballet, is by no means clear. Over the years I have watched various crew members of ships, from Rear Admirals to barnacle scrapers, perform all sorts of baffling physical manoeuvres, and not once have I thought any of it fitted the definition of jiggery-pokery, except on one occasion when I was aboard a very sinister ship which sailed into a clammy mist, in which all sorts of ugly shenanigans took place until, at the last, I was marooned, with several other paying passengers, upon a remote atoll, populated only by squelchy creeping things, and bereft of paper and pencils and writing desks and panels of adamantine hardness. Luckily, the one, brine-soaked, Dobson pamphlet I managed to salvage from the ship was written in his more familiar majestic sweeping paragraphs, with nary a pippet of “abstraction” within it. Its title, by the way, was Popular Games And Pastimes Suitable For Those Marooned On Remote Atolls Pending Rescue By A Ship Of Fools (out of print).

Returning to the pamphlet under discussion, my copy of The History, Theory And Practice Of Jiggery-Pokery, From Ancient Times Up To Yesterday Morning, With Practical Tips And Cut Out ‘N’ Keep Cardboard Display Models For Your Mantelpiece contains neither practical tips nor cut out ‘n’ keep cardboard display models for my mantelpiece, not that I have a mantelpiece in my chalet, for architectural reasons. I suspect Dobson appended these items to his title to woo a wider readership, attracting the kinds of people who like practical tips and the construction of cardboard display models. I once cut out, from a Kellogg’s cornflakes carton, ‘n’ constructed ‘n’ kept, a cardboard display model of the head, just the head, of Henry VIII. But that was long ago, when I was young and tiny, and almost as long ago it was lost. Both are lost, the time of my youth and the cardboard head, lost too, one suspects, the wits of Dobson when he sat down to write his jiggery-pokery pamphlet. Perhaps that was his own kind of jiggery-pokery, as a pamphleteer, to convince us he was a sensible man writing sensible prose, when more often than not he was a nincompoop.

Monkeys And Squirrels

The super soaraway Dabbler is rapidly proving to be the one thing (apart from Hooting Yard of course… so make that one of the two things) that justifies the very existence of het internet, so it pains me to have to chuck a brickbat, but chuck a brickbat I must. Quite frankly, it passeth all understanding that a postage with the promising title Important monkey / flying squirrel insight news signally fails to mention Dobson’s ground-breaking pamphlet A Detailed Account Of How I Provided Emergency Medical Assistance, Despite Having Not A Jot Of Training, To A Flying Squirrel Exhausted And Maimed After Being Pursued And Attacked By A Small Tough-Guy Japanese Macaque Monkey Which Mistook It For A Predatory Bird, With Several Diagrams And An Afterword Quoting A Jethro Tull Song Lyric (out of print).

We tend not to think of the great pamphleteer as the sort of chap to dispense succour to small wounded animals. After all, he was much more likely to throw pebbles at swans, or to rain imprecations down upon puppies. But painstaking research has shown that the “detailed account” he gives is absolutely factual. What happened was that Dobson took a detour through a monkey and squirrel sanctuary while on his way home from a visit to Hubermann’s, that most gorgeous of department stores, where he had bought a large supply of bandages and liniment. His purchases were made with a distinct purpose, for sloshing around in his head was the idea of writing a pamphlet about bandages and liniment as part of a projected series with the collective title Various Things You Can Smear On Wounds And Various Methods Of Protecting Wounds From The Elements. According to his notes, there were to be at least twelve pamphlets in the series, but not a single one was ever written, possibly because of the turn of events in the monkey and squirrel sanctuary.

Close to the perimeter fence, Dobson chanced upon a mewling and maimed flying squirrel, and saw a small Japanese macaque monkey scampering away with squirrel blood dripping from its gob. The pamphleteer put two and two together. Then, quite out of character, he knelt down, applied liniment to the gashes on the flying squirrel, and enwrapped it in bandages. He had a mind to take it home to Marigold Chew, as a prospective pet to replace her recently deceased weasel. Alas, so thoroughly did Dobson apply the bandages that the flying squirrel was suffocated.

The pamphleteer chose a spot close to the Blister Lane Bypass and buried the flying squirrel in a shallow grave. Every day, for weeks afterwards, he visited to place a sprig of dahlias or lupins on the plot, and he wept. He never told Marigold Chew what he had done, and it seems that she never got round to reading the pamphlet, one of the few works of Dobson to be commercially printed rather than typeset and cranked out on Marigold Chew’s Gestetner machine.

The quotation from Jethro Tull which appears on the last page of the pamphlet, by the way, is “So! Where the hell was Biggles when you needed him last Saturday?” from Thick As A Brick. Its significance to the text it accompanies has eluded every Dobsonist who has tried to winkle some meaning from it. I suppose that is one of the reasons we still read Dobson today. He continues to challenge us.

Jars And Moss

Dobson’s pamphlet An Entirely New System Of Moss Drainage, Incorporating Flexible Leather And Lead Pipes, A Plastic Funnel, And A Dobson Jar (out of print) is chiefly notable for the inclusion in its title of the latter item. It is the only known record of this container, as, indeed, it is the single instance of the celebrated pamphleteer claiming to have an eponymous receptacle. The text itself assumes that the reader is familiar with the “Dobson jar”, as if one had a whole row of them lined up in one’s pantry, though of course neither you nor I have ever met anyone who owns such a jar, or knows anybody who has. Blank stares, and possible dribbling, meet the enquirer who haunts antique fairs, car boot sales, and jumble extravaganzas in pursuit of the chimerical container. In any case, one jar is much like the other, as you will know if, like me, you have made a study of jars, and not just any old study but a thorough, rigorous, scholarly study, the kind of study that wins you not just a postgraduate diploma in jar studies, at the awarding of which you happily sport a gash-gold vermilion cap and robe, but a badge, a badge depicting a jar, a sort of Ur-jar, the jar of jars, also of gash-gold vermilion, which you can wear, on your tunic, or cardigan, to display your jarry credentials, in jar circles.

Dobson came late, too late, to moss drainage matters, for this important subject had already been addressed comprehensively by Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles, when he was not turning his attention to the slave trade, witches, lunacy, priests, eugenics, aeroplanes, submarines, hygiene, the action of flowers, the habits of animals, modern novels, Christian ethics, the drink question, microscopic researches, the theory and structure of language, will o’ the wisps, anemology, evolution, visible or luminous music, fogs and frosts, electricity, wooden chessmen, double-furrow ploughs, artificial birds, perpetual motion, diving-bells, vegetation and evaporation. Dobson, of course, wrote pamphlets on some, not all, of these subjects, as the fancy took him. Who has read his pamphlet on artificial birds without weeping? Well, I have, actually. I had a jar at hand, to catch my tears, should I shed any, but I did not. The jar was not a Dobson jar, as far as I am aware, for I do not know if I would recognise a Dobson jar if I saw one. As I have indicated, our pamphleteering titan gives us no clues, in his out of print pamphlet, as to what the jar named after him might look like. I suspect there never was such a jar. I think Dobson was hoping to find a secondary route to immortality, reckoning that even if all his Herculean pamphleteering efforts were swept into the abyss and forgotten, his name would live on forever, or at least for as long as people made use of jars. It was a foolish conceit, but then Dobson was a rather foolish and conceited man.

It is worth pointing out, before I close, that the system of moss drainage propounded by the pamphleteer in his pamphlet is utterly nonsensical, and fails to drain even the tiniest smidgen of moisture from any patch of moss to which it is applied. I should know, because I tried it. There is some moss on a wall I pass by often on my travels, and one gusty wet morning I set about it, following Dobson’s instructions to the letter as best I could. The upshot was a teetering wall, a broken arm, and a patch of moss if anything more moist than it was when I rolled up with my equipment just before dawn. My arm was in a cast for six weeks, during which time moss grew upon the plaster, as it will, if conditions are right, for the growth of moss. I made no attempt to drain it.

Hay In Nosebags

“the Knyght was a little less than Perfect, and his horse did not have a metabolism”

Preamble to A Knyght Ther Was by Robert F Young, Analog Science Fact & Fiction, July 1963

This fragment from a pulp magazine was almost certainly the inspiration for Dobson’s important pamphlet, published, as it happened, on the day of the Kennedy assassination in Dallas, entitled, somewhat inelegantly, A Comparative Study Of The Metabolisms Of The Horses Of Three Knights Of The Realm (out of print).

Dobson begins with a bold declaration:

In this pamphlet I am going to prove, beyond all reasonable doubt and brooking not one whit of opposition, that the horse of Sir Lancelot, of the Arthurian Round Table, had the metabolism of a squirrel, that the horse of his confrère Sir Bedivere had the metabolism of a gnat, and that the horse of Sir Cloudesley Shovell, of later date, had a metabolism so extraordinary and anomalous that science has yet to account for it. My findings, which will completely overturn the accepted wisdom regarding the metabolism of horses ridden by knights of the realm, are backed up by a wealth of evidence only I have had the energy and diligence to winkle out of the documentary record, and this evidence, in the form of a vast scholarly apparatus of footnotes and citations and what have you will be published in a separate series of pamphlets in due course.

It never was – so the reader has to take on trust forty pages of wild assertion, idiotic wittering, equine ignorance, and frankly incomprehensible gibberish, all of it written, as we would expect, in majestic sweeping paragraphs. The pamphlet is remembered today chiefly for the much-anthologised passage about nosebags crammed with hay which, though factually inaccurate, has served as a model for many a novice pamphleteer. I well remember the way these words of Dobson’s transfixed me in my early, faltering stabs at composition, and how for years I was unable to write a finished piece without inserting something about hay in nosebags, no matter what my ostensible subject. It must be said that editors were kind to me. The inevitable rejection letters I received gently pointed out that I could easily delete the hay in nosebags stuff without fatally undermining my prose. But, oh!, I was young and headstrong and I would not countenance the change even of a comma to what I had scribbled so decisively with my propelling pencil on my tablet of notepaper. In those days, I cared not to pound the keys of a typewriter like Mancunian polymath Anthony Burgess. My hero Dobson was a scribbler, and so would I be.

The truth of it was, of course, that without acknowledging the fact I was being smothered under the Dobson cushion, as so many beginners have been. My salvation, and the prompt that allowed me at long last to cast the cushion aside, was a commission from a now defunct magazine, Beasts Of Barnyard And Field, to pen an article about nosebags crammed with hay. I worried and fretted at it so much that, in nervously gnawing my propelling pencil I managed to get a sliver of lead stuck in my craw, and had to be enclinicked. It was the morning of my fifty-first day there when, sprawled on my balcony gazing at the mountains, I sensed a tiny yet dramatic shifting of the integuments within my head, and knew at once that I was free of Dobson. The mighty out of print pamphleteer will always remain my idol, but on that morning in that clinic on that balcony I knew it was possible for me to plough my own furrow.

I tore up the few puny pages of prose I had written about hay in nosebags, and instead submitted to the magazine a piece about swill for pigs. Alas, later that day, listening to the news on the wireless in the clinic’s rumpus room, I learned that the skyscraper housing the offices of Beasts Of Barnyard And Field had collapsed after attack by woodworm and weevils and tiny, tiny beings that bore through cement, and the magazine had ceased publication. Ha!, I thought, I am not going to let that stop me. And it has not.

Dobson’s Abortive Pliny

Here is the list of contents of the tenth book of Pliny The Elder’s Natural History (c. 77-79 AD):

“The nature of birds. (i-ii) The ostrich, the phoenix. (iii-vi) Eagles, their species; their nature; when adopted as regimental badges; self-immolation of eagle on maiden’s funeral pyre. (vii) The vulture. (viii) Lámmergeier, sea-eagle. (ix-xi) Hawks: the buzzard; use of hawks by fowlers where practised; the only bird that is killed by its own kind; what bird produces one egg at a time. (xii) Kites. (xiii) Classification of birds by species. (xiv-xvi) Birds of ill-omen; in what months crows are not a bad omen; ravens; the horned owl. (xvii) Extinct birds; birds no longer known. (xviii) Birds hatched tail first. (xix) Night-owls. (xx) Mars’s woodpecker. (xxi) Birds with hooked talons. (xxii-v) Birds with toes: peacocks; who first killed the peacock for food; who invented fattening peacocks; poultry – mode of castrating; a talking cock. (xxvi-xxxii) The goose who first introduced goose-liver (foie gras); Commagene goose; fox-goose, love-goose, heath-cock, bustard; cranes; storks; rest of reflexed-claw genus; swans. (xxxiii-v) Foreign migrant birds: quails, tongue-birds, ortolan, horned owl; native migrant birds and their destinations – swallows, thrushes, blackbirds, starlings; birds that moult in retirement: turtle-dove, ring-dove. (xxxvi) Non-migrant birds: half-yearly and quarter-yearly visitors: witwalls, hoopoes. (xxxvii-xl) Mernnon’s hens, Meleager’s sisters (guinea-hens), Seleucid hens, ibis. (xli) Where particular species not known. (xlii-v) Species that change colour and voice: the divination-bird class; nightingale, black-cap, robin, red-start, chat, golden oriole. (xlvi) The breeding season. (xlvii) Kingfishers: sign of fine weather for sailing. (xlviii) Remainder of aquatic class. (xlix-li) Craftsmanship of birds in nest-making; remarkable structures of swallows; sand-martins; thistle-finch; bee-eater; partridges. (lii f.) Pigeons – remarkable structures of, and prices paid for; (liv f.) Varieties of birds’ flight and walk; footless martins or swifts. (lvi) Food of birds. Goat-suckers, spoon-bill. (lvii) Intelligence of birds; gold-finch, bull-bittern, yellow wagtail. (lviii-lxl) Talking birds: parrots, acorn-pies; riot at Rome caused by talking crow. (lxi) Diomede’s birds. (lxii) What animals learn nothing. (lxiii) Birds, mode of drinking; the sultana hen. (lxiv) The long-legs. (lxv f.) Food of birds. Pelicans. (lxvii f.) Foreign birds: coots, pheasants, Numidian fowl, flamingos, heath-cock, bald crow or cormorant, Ted-beaked or Alpine crow, bare-footed crow or ptarmigan. (lxix) New species: small cranes. (lxx) Fabulous birds. (lxxi) Who invented fattening of chickens, and which consuls first prohibited? who first invented aviaries? Aesop’s stewpan. (lxxiii-lxxx) Reproduction of birds: oviparous creatures other than birds; kinds and properties of eggs; defective hatching and its cures; Augusta’s augury from eggs; what sort of hens the best? their diseases and remedies; kinds of small heron; nature of puff-eggs, addled eggs, wind-eggs; best way of preserving eggs. (lxxxi f.) The only species of bird that is viviparous and suckles its young. Oviparous species of land animals. Reproduction of snakes. (lxxxvi-vii) Reproduction of all land animals; posture of animals in the uterus; animal species whose mode of birth is still uncertain; salamanders; species not reproduced by generation; species whose generated offspring is unfertile; sexless species. (lxxxviii-xc) Senses of animals: all have sense of touch, also taste; species with exceptional sight, smell, hearing; moles; have oysters hearing? which fishes hear most clearly? which fishes have keenest sense of smell? (xci-iii) Difference of food in animals: which live on poisonous things? which on earth? which do not die of hunger of thirst? (xciv) Variety of drink. (xcv f.) Species mutually hostile; facts as to friendship and affection between animals; instances of affection between snakes. (xcvii f.) Sleep of animals; which species sleep?”

Now, imagine the scene. It was shortly after breakfast time on a cold and storm-tossed morning in the 1950s at the home of the twentieth century’s most magnificent pamphleteer. Dobson had eaten his bloaters. Marigold Chew had something eggy. They were still sitting at their breakfast table. Outside, hailstones were pinging.

“Marigold, o my darling dear,” boomed Dobson, “I have devised a marvellous plan! Listen carefully. You often comment upon what you consider to be my breathtaking ignorance of the natural world. And though I usually swat away your charges, as a giant may swat away a dwarf, I have, this day, found within myself a reservoir of humility, and I must admit there is a certain truth in what you say.”

Marigold Chew interrupted here, to suggest she capture Dobson’s words upon a tape recorder for the settling of any future contretemps, but the pamphleteer pressed on.

“That being so,” he said, “My plan is to increase my knowledge in the best way possible, and what method could be more efficacious than to write a book about what I do not know? And not just any book. I shall take as my guide that great ancient encyclopaedia by Pliny The Elder, the Natural History, and rewrite it in its entirety! To ensure I cover the sweeping width and breadth of all natural phenomena, I shall follow slavishly the chapter and section headings of the great work, but, subjoined to them, the texts shall be my own! Is that not a fantastic plan and a superb way to extend my knowledge of that which you claim me to be ignorant.. of, again, I think, if I am to be grammatically sound?”

“Are you sure you mean ‘subjoined’, Dobson?” asked Marigold Chew, who was in chucklesome mood.

“I am not one hundred percent certain, no, but let that pass, o my inamorata. The thing is, I have decided to begin the project this very day, not at the beginning, but plunging straight in to the tenth book of Pliny, which you will recall is the one in which he addresses matters ornithological. That is an area in which you suggest my ignorance is boundless and unfathomable, so it will be the perfect test bed. And no, I am not sure I mean ‘test bed’, but let that pass too, for the time being.”

“I am quite happy to do so,” said Marigold Chew, “For now my eggy breakfast is digested, I am going off and out to a beekeeping bonanza jamboree. Get thee to thy escritoire, and when I return I shall be happy to have you read to me the initial scribblings of your Natural History, a book I am sure will knock Pliny from his plinth.”

Dobson took this repartee in good part, scurried to his escritoire, sharpened a pencil, and flung open his dusty copy of Pliny at the tenth book. The nature of birds. (i-ii) The ostrich, the phoenix, he read. He closed his eyes and tried to summon a vision of an ostrich and a phoenix, first separately, then together. He was determined not to cheat by reading what Pliny The Elder had had to say on the subject nearly two thousand years ago. Then the pamphleteer shook his head, like a man waking from a jarring dream, opened his eyes, and began to scribble with his sharpened pencil on the first page of a brand new notepad.

Both the ostrich and the phoenix, he wrote, are birds, the one real, the other mythical. On the front of the head of the real bird, there is a beak. And, lo!, what do we find on the front of the head of the bird of myth? It too has a beak! And this is not the only feature they have in common, for the bodies of both birds bear plumage in the form of feathers.

Dobson looked upon what he had done, and saw that it was good. No doubt there would be more to say about both the ostrich and the phoenix, but he felt he had, at the very least, cracked the method he planned to employ. Pliny would be his guide, but only his guide. The grand sweeping paragraphs of majestic prose would be Dobson’s alone. He went to take a post-breakfast nap.

When he awoke, the pamphleteer’s brain was befuddled after a series of dreams, the details of which, so vivid in sleep, vanished pfft! the instant his head rose from the pillow. He opened a can of revivifying Squelcho! and poured it into a tumbler, then sat again at his escritoire to consult his Pliny. Eagles… vultures… hawks… owls… woodpeckers… it was a long, long list of things with beaks and feathers! Dobson threw his pencil across the room, donned his greatcoat and his Belgian Post Office Inspector’s boots, and went out in the teeth of the hailstorm to trudge along the towpath of the filthy old canal to clear his head. He saw a number of birds while on his trudge, not one of which was either an ostrich or a phoenix. He threw a pebble at a swan. He stopped in at Old Ma Purgative’s Canalside Lobster Hatchery ‘n’ Winter Sports Togs Bazaar, and browsed among the lobsters and the winter sports togs, but in spite of the Old Ma offering bargains galore in a special ‘hailstorm sale’, Dobson, enmired in penury as ever, bought nothing. Eventually he trudged back home, passing the puddle in which the pebble he had thrown at the swan had somehow fetched up, as pebbles do. And as pamphleteers do, he returned to his escritoire, sharpened another pencil, and, jaw set in determination, cast his eye over the Pliny. Peacocks… bustards… swans… hoopoes… partridges… goat-suckers… this last reminded Dobson that he had a goat-milk popsicle in the refrigerator, and he was about to go and fetch it, for a midmorning snack, when, towards the end of the contents of Pliny’s tenth book, he read instances of affection between snakes and a bomb exploded inside his brain.

Suddenly Dobson recalled the dream from which he had awoken befuddled after his nap. He remembered it in every last detail, for it was his recurring dream, the one that flickered in his sleeping cranium on so many, many nights, and in so many, many daytime naps, and had done since infancy. He turned to a fresh page of his notepad, and began scribbling.

When I was a tot, he wrote, I had a favourite bedtime story which I implored my ma or pa to read to me before I fell asleep. I drank my bedtime beaker of milk of magnesia and settled my little head on my little pillow, and listened, night after night, to the tale which, ever since, has haunted my dreams, and about which it is incomprehensible that I have not written a pamphlet until today. Well, thanks to Pliny The Elder, now I can address that omission. The story began as follows:

Once upon a time there was a boa constrictor named Dagobert. He was loitering on a verdant slope when he happened to spot a passing vole. Dagobert uncoiled himself, pounced, sank his fangs into the tiny vole, and gulped it down in one fangsome mouthful. But before his digestive juices could begin to reduce the paralysed but yet living vole into nourishing pulp, along came a viper named Clothgard.

“My oh my!” thought Dagobert, “What a lovely viper she is. I feel a great pang of affection for her.”

Clothgard herself was a sore vexed viper, for she had not eaten for many days.

“O boa constrictor loitering on the verdant slope, canst thee help a sore vexed viper who has not eaten for many days? My name is Clothgard,” hissed Clothgard.

So mighty were the pangs of affection felt by Dagobert that he immediately regurgitated the vole and offered it to the famished viper.

“Why thank you,” she hissed, “You are quite the most charming boa constrictor it has ever been my pleasure to meet.”

There was more to the story, much more, but it was always around this point that, as a tot, I fell into my golden slumbers, and ma or pa placed the storybook gently by my pillow and tiptoed away.

This you will recognise, I expect, as the opening of Dobson’s important pamphlet The Significance, In My Long-Ago Infancy, Of An Undigested Vole (out of print). He was still scribbling away furiously, possessed by a pamphleteer’s demons, when Marigold Chew arrived home. Thinking he was at work on his revision of Pliny, she did not interrupt him, but went straight into the back garden with the new bees she had brought back from the bonanza jamboree. Not until a few days later, when she asked Dobson if he had yet written his chapter on the nature of puff-eggs, addled eggs, and wind-eggs, did she learn that the pamphleteer had abandoned his Pliny.

“Oh that,” he said, over breakfast, “It’s just one bird after another. I can’t be doing with it.”

Dobson In Dreamland

According to Hargrave Jennings, in Curious Things Of The Outside World : Last Fire (1861), “There are moments in the history of the busiest man when his life seems a masquerade. There are periods in the story of the most engrossed and most worldly-minded man, when this strong fear will come, like a cloud, over him; when this conviction will start, athwart his horizon, like a flash from out a cloud. He will look up to the sunshine, some day, and in the midst of the business-clatter by which he may be surrounded, a man will, in a moment’s glance, seem to see the whole jostle of human interests and city bustle, or any stir, as so much empty show. Like the sick person, he will sometimes raise his head, and out of the midst of his distractions, and out of the grasp which that thing, ‘business’, always has of him, he will ask himself the question, What does all this mean? Is the whole world awake, and am I asleep and dreaming a dream? Or is it that the whole world is the dream, and that I, in this single moment, have alone awakened?”

That great twentieth-century pamphleteer, Dobson, woke up in this state of mind every single morning of his adult life. And that was not the end of his confusion, for Dobson was a great one for naps, he took a nap daily, very often more than one, plural naps, as it were, and each time he woke from his naps he likewise asked himself the questions posed by Hargrave Jennings, as he had already done on the morning of the day, when first he awoke.

“Do you have the slightest idea,” asked Marigold Chew, one blustery blizzardy Monday in the late 1950s, “How tiresome it is to have you lumbering about the place like a dippy person, asking the kinds of questions most sensible people stop posing when they outgrow their years of teendom?”

Dobson’s reply to this perfectly reasonable query was most annoying.

“Are you really speaking, Marigold, or am I just imagining this conversation within the wispy mysterious mists of mystery?”

Marigold Chew was holding a handful of pebbles, and proceeded to throw one at the pamphleteer. No, that’s not right. Marigold Chew was holding a Pebblehead paperback, and it was this she threw across the room. The book was Pebblehead’s latest bestselling potboiler, The Interpretation Of Breams, a guide to foretelling the future using a combination of fish and recordings of lute music. Luckily, the book missed Dobson’s head by an inch.

“I am going to go about my business in the real, palpable world, Dobson,” announced Marigold Chew, “If you choose to waft about the place in a moonstruck daze, that is up to you. But it won’t get any pamphlets written!” and she swept out of the house into the blizzard, bent upon her real and palpable business, whatever it might have been that day.

Dobson picked up the Pebblehead paperback from the floor and leafed through it, distractedly. He read a few lines here and there, and decided to go out to the fishmonger’s and the record shop. But he got no further than the chair on which he sat to don and to lace up his Canadian Snowplough Mechanic’s boots, for, yet enmired in his dreamy daze, he wondered if the chair, the laces, the boots were but figments. “Figments” made him think of figs, and then of Fig Newtons, a type of biscuit of which, at this period, he was inordinately fond, and, with his right foot encased in a boot the laces of which were not yet tied and his left foot merely ensocked, he rose from the chair and made for the cupboard wherein the biscuits, and similar snack items, were stored. When he stood, he was, in boot and sock, necessarily lopsided, and this being so, Dobson lost what balance he had, and toppled, bashing his bonce on the wainscot.

He was unconscious for some minutes, during which time he really did dream, of the glove of Ib and of his weak Bomba, whatever that might mean.

And of course, when he woke, sprawled on the floor, the pamphleteer’s swimming brain was yet again prompted to ask the Hargrave Jennings questions. Round and round we go, in an endless cycle, akin to the orbit of the planets around the sun.

Marigold Chew was still out and about, so Dobson was alone in his daze. Now wide awake, but still unable to gain a foothold in the real, palpable world, he mooched about the house as a person might blunder about in a thick fog, what they used to call a “pea-souper” because of the supposed similarity of the cloudy density of the air to the consistency of soup made from peas, not to be confused with pease pudding, which is, as its name suggests, a pudding, not a soup. Dobson was thinking neither of soup, nor of the Fig Newtons, which he had utterly forgotten. He was doing things such as tapping the walls with his fingertips, peering carefully at curtains, opening and then closing doors, or in some cases leaving them ajar, as he tried to grasp what was real and what was not. Stumbling past an airing cupboard into the bathroom, he was astonished, in a bleary way, to come face to face with a monster of the deep, wallowing in the tub. It was bloated, lascivious, coarse, and repulsive, rather like Gertrude Atherton’s vision of Oscar Wilde, except that it had fins and hideous trailing tendrils, like those of a jellyfish. One such tendril now lashed out and struck Dobson across the face, leaving, not just a vivid crimson stripe, but droplets of an unbelievably aggressive toxin which seeped in seconds through his pores and began ravaging his innards. The pamphleteer toppled once again to the floor, this time of his bathroom rather than of his kitchen, still wearing one boot, but now he was convulsed by fits, as if he were Voltaire’s officer with pinks in his chamber alluded to in another passage from Hargrave Jennings’ very sensible book, and, like the officer, Dobson lost his senses.

In the tub, the sea monster now began to gurgle, and to splash about. Suddenly, through the bathroom window crashed Father Ninian Tonguelash, the Jesuit priest and self-styled “Soutane-Attired Nemesis Of Sea Monsters”, clutching in one gloved hand a harpoon and in the other a crucifix. Then…

Then…

Then… I awoke, and I realised that all I have just written was a dream. Of course it was! Dobson did not become the titanic pamphleteer he was by faffing about the place all muddleheaded. When he woke up, every day of his adult life, he knew exactly where he was, and if perchance there was a smidgen of doubt in the matter, he would in any case plunge his head into a bucket of icy water, just to be on the safe side. How foolish of me to confuse the hallucinations of my sleeping, pea-sized brain with the iron truth!

Poultry Yards Of The Grand Archdukes

Within minutes of beginning my research into the poultry yards of archdukes, I struck gold. I suppose I should not have been surprised to learn that it was a topic to which Dobson had turned his attention, in his pamphlet The Poultry Yards Of The Grand Archdukes (out of print). Alackaday!, as Hadrian Beverland would put it, I then struck base metal, for it turns out that this is one of the rarest of the rare of Dobson pamphlets, and I could not get my hands on a copy try as I might, not that I tried very hard, having other things on my mind, such as Pantsil’s performance in the World Cup, guff, pomposity, and potato crisps. Of which, more later, if it please your Lordship.

Now the unobtainability of a pamphlet would deal a knockout blow to a weedy, milksop researcher, but I am made of sterner stuff. I gulped down a beaker of Squelcho! and, at dead of night, I stole out to the weird woods of Woohoohoodiwoo and sought out the Woohoohoodiwoo Woman. I found her crouching in a patch of nettles, moving her withered arms in some incomprehensible but no doubt eldritch fashion, and muttering gibberish. Good old Woohoohoodiwoo Woman!, I thought, she never lets you down. Not, at least, if you remember to bring her a gift, as I did. I greeted her and handed over a rather smudged back number of the Reader’s Digest. I had no idea to what weird and spooky use she would put it, but it is better not to ask. She gave the magazine a couple of gummy bites to make sure it was genuine, and then asked me, in her weird woohoohoodiwoo voice, what I wanted. I cleared my throat.

“Are you familiar with the out of print pamphleteer Dobson?” I asked her. When I spoke aloud the great man’s name, an owl hooted and a wolf howled. The Woohoohoodiwoo Woman’s head moved slightly, in what might have been a nod. It was either that or a magical spasm. I pressed on.

“There is an unobtainable pamphlet by Dobson which I feel impelled to read, oh Woman of Woohoohoodiwoo,” I continued, “And I was wondering if, through your tremendously strange powers, you might be able to commune with transient shimmerings of ectoplasmic doo-dah and somehow have transmitted to you the full text of this pamphlet, entitled The Poultry Yards Of The Grand Archdukes, and declaim it to me, here in the weird woods in moonlight, while I scribble down what you say in my notepad with my propelling pencil.” I patted my pocket to indicate that I had come prepared with these essential items.

The Woohoohoodiwoo Woman did some business with a toad and a newt and a hacksaw and some parsley and the bleached and boiled skull of a starling and a handful of breadcrumbs, and there was a mighty flash of eerie incandescence across the sky and a boom as of thunder and then she began to writhe in hideous jarring contortions as the night air grew chill as the grave. Then she began to babble, and I started scribbling.

When we were done, I patted the Weird Woman on her weird head, promised her further back copies of the Reader’s Digest or Carp Talk!, her other favourite periodical, and headed for home clutching the precious recovered text. I had a long day’s work ahead of me, transcribing the scribble in my notepad using my iWoo, a fantastic new device from Apple specifically designed for the transcription of unearthly hallucinatory babblings into tough sensible prose. I chuckled to myself, wondering what Dobson would have made of our twenty-first century technology. Somehow I could not imagine the great man Twittering or Facebooking or posting videos on YouTube, though there is of course that tantalising paragraph in his pamphlet Tantalising Paragraphs About The World O’ The Future (out of print) where he seems to be hinting at some kind of hand-held apparatus called an iRuskin. I must look it up and parlay my observations into a postage here one of these days.

As soon as I got home, just after dawn, I switched on or, as they say nowadays, powered up my iWoo, and left it to bleep and hum while I fixed a solid breakfast. This involved more eggs than you can shake a stick at, which is a goodly number of eggs, I can tell you. This is my own breakfast recipe, called Hitchcock’s Nightmare, or, alternatively, Orwell’s Glut. All of my many and various breakfast recipes are named after writers, painters, and film directors, and I hope one day to cobble them together into a compendium. But a more urgent task was at hand. What, I wondered, had Dobson had to say about the poultry yards of the grand archdukes in that rare, o rare!, pamphlet?

The iWoo hissed and juddered like some living organism as it tackled the bonkers babbling of the Woohoohoodiwoo Woman, but before sunset I had a print-out. It ran to forty pages of densely-set text, cleverly imitating the authentic look of a Gestetnered pamphlet direct from Marigold Chew’s shed. I was too exhausted to read it then and there, so I shoved it into a drawer and went to bed.

During the night I had that dream about the Kibbo Kift again.

The next morning, after a breakfast I call a Claude Chabrol Special, I sat down to read. I was careful to bear in mind that what I was reading was not Dobson as such, but Dobson as filtered through the eerie inexplicable powers of the Woohoohoodiwoo Woman, a different text entirely. Nonetheless, it was the nearest I could get to the pamphleteer’s own words.

Dobson, or the WooDobson, began by listing the grand archdukes whose poultry yards he had studied. It was an incredibly long and tedious list, packed with Ludwigs and Viggos and Hohenhohens and Gothengeists and Ulrics and Umbertos. Here and there, a few biographical or historical details were scattered about, but nothing about poultry yards nor, indeed, disgusting rabbits. Next came one of those Dobsonian digressions, sometimes fascinating, sometimes infuriating. This one was firmly in the latter camp, being an extended meditation upon stars and yeast, neither of which topics the pamphleteer seemed to have a clue about. By the time he had finished wittering, I was halfway through the recovered pamphlet, and still waiting to learn about its ostensible subject matter. I began to wonder if the Woohoohoodiwoo Woman had played a joke on me. Had she really been in contact with ectoplasmic beings from a realm beyond our puny understanding, or was she just raving? I wanted to trust her, not least because I had paid good money for that back number of the Reader’s Digest from Old Ma Purgative’s Anti-Communist Secondhand Periodicals Shoppe.

But of course I need not have worried. After some closing flimflam about boiled yeast, the WooDobson at last got to the matter in hand. Here was the sentence that made me sit bolt upright:

It is patently obvious to anyone who has studied these things that all grand archdukes, maintaining poultry yards upon their estates around which disgusting rabbits prowled, did so because of a fanatical devotion to the cause of Unreason.

He goes on to explain. Unfortunately, this is where the Woohoohoodiwoo Woman’s channels of communication with the mysterious realms seem to have broken down a tad.

I say “patently obvious” because it is both patent and obvious. Consider the Ancien Regime. Consider it again. Imagine yourself strutting about the corridors of the archducal palace. Is your path blocked by hens? It is! Why are the hens not in their coop in the poultry yard? Hear them clucking. If you could translate their clucking into human speech, specifically High Germanic speech, as spoken by quite a number of grand archdukes, what do you think they would be saying? “Eek! Eek! We are in fear of the disgusting rabbits who skulk about the perimeter of our yard!” You might argue that rabbits are one of the last animals on earth whose method of propelling themselves hither and thither could be described as “skulking”. You might argue that, but do you want to be seen arguing with hens, in your palace corridor, by one of your footmen or valets? “Ho ho ho”, they would sneer, your minions, later, downstairs in their pantry, “The old fool was arguing with hens. Who ever heard of such a thing?” Thereafter they would treat you with contempt and even come to question your Archdukedom. The lettered ones among them might start reading insurrectionist pamphlets produced by beardy German revolutionaries. Better by far never to argue with hens in the corridor, no matter how panic-stricken they appear. Gather them up, one by one, and put them right back in their coop, in the poultry yard. Send a rider to dash on horseback to the Landgrave, in his distant fastness, to alert him to the presence of disgusting rabbits. His forces may sweep in, within days or weeks, or not at all, for you can never second guess the Landgrave. He has his own hens, in his own poultry yard, where he argues with them all day long, for much interbreeding in his noble line has made him soft in the head. See him dribble. See him drool. See him argue frantically with this hen and that hen, hauling himself around the poultry yard on the crutches which support his withered legs. The legs of his hens are withered too, as are the legs of the disgusting rabbits who surround his castle, yes, he has his own disgusting rabbits to contend with, as do all Landgraves and Margraves and Grand Archdukes in the Ancien Regime, you would do well to learn that and to cease your whining. Strut your corridors as you may, for one day all will crumble, the footmen and valets will break out of the pantry and run amuck, and there will be traffic between the terrified hens and the disgusting rabbits, oh, odious, odious, but now you have glimpsed what is to come you must be a fierce and ruthless Grand Archduke, in all your finery, though it fray to tatters..

I will leave it to the experts to judge if this is the authentic voice of Dobson, or the witless prattle of the Woohoohoodiwoo Woman. Either way, it takes us some way towards a better understanding of the Hens of Unreason, and that is all we set out to do, in our modest way, on this summer’s day.

Flight Patterns Of The Common Shrike

One rain-lashed November morning in the latter half of the 1950s, Dobson awoke from uneasy dreams and succumbed to a fit of ornithomania. At the breakfast table, after fletcherising his steamed dough ‘n’ gooseflesh flan, he announced to Marigold Chew “O inamorata o’ mine! What the world needs is a pamphlet, decisively written, on the flight patterns of the common shrike.”

Marigold Chew let this intelligence sink in while she munched her kedgeree. This was the period, it ought to be noted, when the out of print pamphleteer and his belle kept to differing breakfast menus, later to be chronicled in the pamphlet-cum-recipe book A Thousand Breakfasts In Five Hundred Days (out of print).

Munching done, Marigold Chew asked pointedly, “Are you intending to pen this pamphlet yourself, Dobson?” to which the pamphleteer replied, after a long pause while he masticated a mouthful of flan thirty-two times, “Yes, of course!”

Marigold Chew sighed. “Dobson,” she said, not unkindly, “You know nothing of the shrike. I doubt you could tell one apart from a robin or a starling or a pratincole or even a vulture. How the hell are you going to write, decisively or otherwise, about the flight patterns of a bird of which your ignorance is limitless?”

“I have a one word answer to that,” replied Dobson, “Research!”

So it was that, when his breakfast was fully digested, Dobson clambered into his Galician Zookeeper’s boots, donned a threadbare waterproof, and stalked out into the rain. He made for the top of Pilgarlic Tor and stared at the sky for hours. When he returned home, he was drenched, and dusk was descending.

“Well?” asked Marigold Chew, “What have you learned?”

“The sky is a vast expanse,” said Dobson, “Across which clouds scud, and from these clouds falls rain, now as drizzle, now in sheets, hence the puddle forming at my feet which I shall mop up with a mop on the end of a stick when I have done enlightening you, my darling dear. From time to time, below the scudding clouds, birds soar and swoop across the sky. Some go flitting until they can no longer be perceived by the human eye, some come into land on the branches of trees or in nests built high or low in trees or even in hedgerows. There are many different types of birds, many more than the ones you catalogued over breakfast this morning. Each has a distinctive manner of keeping itself airborne. Through keen and judicious observation, one can learn to differentiate one type of bird from another, purely from its method of flight, without needing to get close up to it, for example while it is resting in its nest or on a tree-branch. As my pamphlet will be devoted exclusively to the common shrike’s flight patterns, that closer observation in the nest will not be necessary. That is fortunate, for I much prefer to stand windswept and rain-lashed upon the top of the tor than to be hunkered in shrubbery for hours on end, where I would be subject to biting by insects and other things that crawl upon the earth, and in shrubs.”

“There are goos one can smear upon the skin to repel such creatures,” said Marigold Chew, waving her hand towards a wall-mounted cabinet wherein such goos were stored.

“That may be so,” said Dobson, “But if you are listening attentively you will grasp that for present purposes I need no such repellant.”

“So will you be standing atop Pilgarlic Tor again tomorrow, staring at the sky?” asked Marigold Chew.

“I will not,” said Dobson, “For tomorrow I will be consulting works of ornithological reference in the library.”

And lo! it came to pass. The following morning, after a breakfast of eggy buns (Dobson) and lightly grilled hen-head with tomatoes (Marigold Chew), the pamphleteer was to be found poring over an enormous ornithological reference work in the ornithological reference library reading room. In those days, libraries were havens of quiet in what Pratt dubbed “the hurly burly of the urban conurbation”, and the only sounds to be heard were the frantic scraping of Dobson’s very very sharp pencil as he scribbled upon his jotter, and the strangulated choking of a fellow bird researcher with a predilection for high tar cigarettes. Dobson was making notes from his study of The Boys’ And Girls’ Bumper Book Of Shrikes. He copied out one passage in its entirety:

Now, tinies, let me tell you why the shrike is known as the “butcher bird”. You see, it is a rapacious and violent little birdie, and it likes to entrap in its talons insects, small birds and even teeny weeny mammals like fieldmice and shrews. Once caught, it impales its victim upon sharp thorns. This helps it to tear the flesh into smaller, more conveniently-sized fragments, and serves as a sort of pantry or larder so the shrike can return to the uneaten portions at a later time. Its call is strident. You will probably have nightmares about it now, but it is well to learn that nature is a realm of blood and gore.

“How did you get on at the library?” asked Marigold Chew when Dobson returned. He had trudged home in a downpour, and a puddle was forming around his feet, which today were clad in a pair of Paraguayan Mining Inspector’s boots.

“It looks as though I will have more mopping up to do, o light of my life,” said Dobson. “You will no doubt be pleased to hear that I have formed a plan of campaign for the accomplishment of what I suspect will be one of my most important pamphlets.”

“I am glad to hear it,” said Marigold Chew, who was knocking back a beaker of some fluid she had strained through a sieve earlier that day. Its colour was indescribable, and it was pip free.

Dobson took his jotter from an inside pocket of his raincoat.

“Listen to this!”, he said, in an excitable voice, “The shrike is a rapacious and violent little birdie, and it likes to entrap in its talons insects, small birds and even teeny weeny mammals like fieldmice and shrews. Once caught, it impales its victim upon sharp thorns. This helps it to tear the flesh into smaller, more conveniently-sized fragments, and serves as a sort of pantry or larder so the shrike can return to the uneaten portions at a later time. Its call is strident. And that’s not all, but you get the gist.”

“I do,” said Marigold Chew, “But what is your plan of campaign and when are you due to set it in motion?”

“Using keen and judicious observation, from atop Pilgarlic Tor, I will wait to spot a bird impaling an insect or a smaller bird or a fieldmouse or a shrew or some other tiny mammal upon a thorn. ‘That,’ I will say to myself, possibly out loud, ‘is a shrike!’ It will then be a simple matter of watching it fly away from the thorn and to trace, with my pencil, in my jotter, the patterns it forms in the sky. This diagram will then form the basis for an accompanying text, which will describe the patterns, in decisive prose.”

The next morning, Dobson ate lobster for breakfast while Marigold Chew had mashed up cake ‘n’ crumpets ‘n’ cornflakes. Then the pamphleteer headed out for Pilgarlic Tor in the torrential rain. He stationed himself in the vicinity of a thorn bush, near the summit, and watched, keenly and judiciously, all day. That was Thursday. Friday, Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday were identical in all particulars except, of course, for the breakfasts. By the time dusk descended on the second Thursday, Dobson was soaked to the skin and had yet to spot a shrike. He returned home crushed and despondent. Marigold Chew could tell from the misery etched upon his countenance that his plan of campaign was yet to bear fruit, but as the pamphleteer stood in a puddle in his Latvian Ice Rink Attendant’s boots, contemplating the mopping he would shortly be engaged in, she asked, “Did you spot a shrike today, Dobson?”

“I did not,” he moaned, in a voice ancient and sepulchral.

“I did,” said Marigold Chew, “Just after you left this morning I went out into the garden to cast my gaze admiringly upon the hollyhocks, and gosh, all of a sudden a bird swooped into view, a newborn hamster struggling in the vicious grip of its talons, and I was jolted by a wave of nausea as I watched the bird impale the poor tiny thing upon a thorn in the thorn bush next to the hollyhock patch beside the shed. Somehow I managed not to vomit all over the lawn, and I realised the bird was a shrike, so I ran indoors for my sketchpad and propelling pencil and rushed back out in time to see the shrike fly away, thereupon executing a highly accurate rendering of the patterns it formed in the sky until, some minutes later, it was lost to view in the overcast grey immensity of the rain-raddled empyrean.”

“And you’re sure it wasn’t a pratincole?” asked Dobson.

“As sure as eggs is eggs,” said Marigold Chew, brandishing the relevant page of her sketchpad in the pamphleteer’s face, now transformed by joy.

“This is fantastic news!” cried Dobson, and he sprang forward and clutched Marigold Chew in an embrace of boundless love. And that is why the pamphlet Flight-Patterns Of The Common Shrike by Dobson (out of print) has the subtitle With A Tremendously Accurate Diagram by Marigold Chew.

In closing, it is worth noting that Dobson’s text, far from being decisive, is incoherent, jumbled, and in places quite potty, probably because in the bliss of their wild embrace, Marigold Chew’s sketchpad was dropped into the puddle of rainwater, and became smudged. The diagram as published was newly drawn, from memory, a few days later, and was by no means as tremendously accurate as claimed. In fact, a reputed ornithologist has said that the flight patterns represented are typical, not of the shrike, but of the pratincole.

Chalet O’ Prose

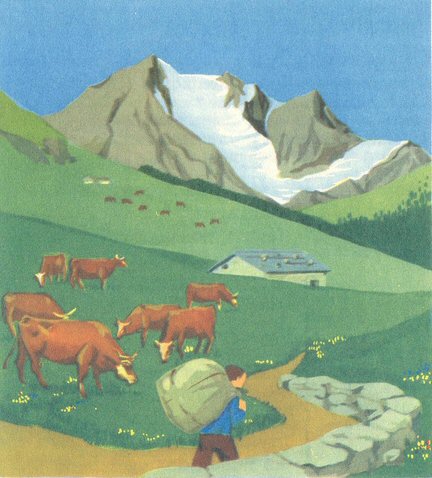

Pebblehead, that titan of the potboiler, has always kept secret the precise whereabouts of his legendary “chalet o’ prose”, wherein he taps out the billions of words of his bestselling paperbacks. On a recent hiking holiday, however, the noted daubist Rex Daub stumbled upon the location, and was able to execute a rapid daub in his portable hikers’ daubum.

The chalet o’ prose itself remains half hidden behind a verdant slope. In the foreground, we see postie struggling up the lane heaving a sack full of fan mail. You will note that he is not wearing a postie’s uniform. That is because, in this mountainous region, wherever it is, all the posties are amateurs, a tradition harking back to the days of King Vud. This lame and pocky monarch took against professionalised posties in uniform from an early age, after a tantrum. It was an opinion from which he never wavered, and his first act upon his coronation was to grant crown licences for postal delivery to a gaggle of peasant amateurs. The existing uniformed posties were shipped off to a remote and barnacle-encrusted atoll.

Also in the picture we see Pebblehead’s famous “seven cows”, munching grass on the verdant slope. The paperbackist has written movingly of these cows, or of six of them at least, and rather more dispassionately about the seventh, in a series of cow-related potboilers. Clockwise in the picture, starting from the largest cow, we see Spinach, Toffee Apple, Miliband, Chlorophyll, Banana Brain, Graticule and Gaston Le Mesmer, all of them familiar to readers of the series, but not, until now, visually, caught brilliantly as they are by Rex Daub’s daubing.

Beyond the chalet o’ prose, the roof of which we see, blue, blue, there is some other stuff in the background, but Rex Daub may have invented this just to finish off his daub. It is a tendency he has, when in a hurry, as he often is, whether or not on a hiking holiday. For further particulars see A Pedestrian Memoir Of Hiking Holidays Accompanied By Noted Daubist Rex Daub by Dobson (out of print).

Letter From A Werewolf

A letter arrives from a werewolf. It is rather difficult to read, as the notepaper on which it has been written is soaked in blood and vestiges of entrail, but I have done my best to decipher and transcribe it:

Dear Mr Key : As a werewolf, I feel I must take issue with your assertion that Dobson was wrong about me and my kind. I realise you were just echoing the witterings of young Ted Cack, but you have not subjected them to proper critical scrutiny and appear to believe every word of his tiresome book. Oh, and it may well be “densely argued”, in the sense that we use “dense” as a synonym for “thick”, “stupid”, or “brain-fuddled”, but to describe his prose as “pretty” is preposterous. The Cack book clunks along like some sort of leaden clockwork robot brimful of elephant tranquiliser. Do not start arguing with me that my analogy is flawed, in that a chemical tranquiliser would have no effect upon a robot’s mechanics, for I have actually stuffed the innards of a robot with mind-numbing powders from sachets, so I know whereof I write. The robot’s progress, clunking along the lane towards the lab, was just like Ted Cack’s prose, in terms of its apprehension by the average werewolf. Not that I consider myself average, by the way. I am just making a point. I inhabit a sphere far above and beyond the average werewolf. I am fantastic and magnificent, as you would know had you ever seen me in my sphere.

It is in fact that sphere that I am writing to you about, for it is located on the island o’ werewolves, the existence of which both you and Ted Cack deny. It is a perfect sphere, constructed, much like a bird’s nest, of matted fur and twigs and duff, and it is punctured with breathing holes, through which I snort. It hangs from a hook in my cave, alongside my caged toads. This is where I stay between full moons, reclining in my werehammock, by turns whistling, puffing on acrid Lithuanian cigarettes, reading Pliny, Herodotus, and Jeanette Winterson, and taking werenaps. Occasionally I might play with my toads, goading them until the precious stones embedded in their heads glow, oh! so brightly. It is a good thing to amass such wealth, when one is a werewolf, for who knows when even we may be plunged into penury due to a credit crunch?

Outside my cave, the island, my ancestral homeland, is bathed in a perpetual milky light. I do not know why it is milky. There are of course other caves, and other werewolves, those who have made it back here, as I did, by marauding around the docks until we were able to slink aboard a ship under cover of night. I myself managed to skulk aboard a tugboat moored at the benighted seaside resort of O’Houlihan’s Wharf. As soon as it chugged away from shore I went on the rampage, howling and slashing and sinking my fangs into anything that moved. Most of the crew jumped into the sea rather than have their throats ripped out, so I was very soon in sole command. I seem to recall that the tugboat was called “Manley Hopkins”. Blood and gore dripping from my leathery lips, I steered her out into the vast expanse of the ocean, following my guiding star. Just as the Magi followed a star to find the infant Jesus, so we werewolves have our own star, up there in the heavens, to bring us home. I have absolutely no idea how it works, but it does, you can rest assured on that point. The hard bit is working out which of the myriad stars blazing in the firmament is the one you are meant to be following. No handy werecharts of the heavens have ever been drawn, probably because as a general rule we werewolves are clumsy and cackhanded with paintbrushes and pencils. That is true even of me, despite my all round general majesty. So I drifted about in “Manley Hopkins” for a few days and nights, gobbling up the cold vitals of the slaughtered crew when I became peckish, and howling at seabirds to pass the time. Occasionally I would fix a star with a gaze of my yellow eyes and mentally interrogate it. Are you the werestar that will guide me home to my island?, I would ask. But the stars never answer. They just glitter, silent in a chaotic universe.

I found my star. On the third or fourth night aboard the tugboat, far from land, I noticed a flock of wereguillemots, disposed across the sky such that they formed an arrow, or directional pointing device, clearly leading me to a bright tiny speck. I howled and I set the engine a-chug on its last gallon of fuel, and took the steering wheel in my clumsy paws. With the rising of the sun, I saw land on the horizon, shrouded in sea mist. My heart pounded in my hairy lupine chest. It was the island o’ werewolves. And it was no myth! The island is as real as the rock or pebble kicked by Dr Johnson on that memorable day when he kicked a rock or pebble to prove a point. And I kicked and bucked as I leapt, intrepid and superb, from boat to shore, home at last.

It is true that in the title of his pamphlet Dobson calls my island mythical, that in his text he suggests that it is merely a hallucination within my brain and the brains of other werewolves. If that were so, could I swing here in my werehammock? Could the walls of my cave drip with the blood of savaged werevictims? Would that milky light illumine scenes of such fecund beauty, the hollyhocks and rhododendrons and petunias, the furze and vetch and watercress, the limpid pools and the roaring waterfalls, the manicured lawns, the golf links, the running track?

Ah, the running track. You know, I think I will put aside my Pliny and stretch my legs. This island has many weasels and stoats and badgers to which I can lay chase, round and round the track, round and round, until I pounce upon them just past the flagpole, and rip them to bloody pieces, howling and howling under the silver moon.

The Mythical Island

For those of us whose knowledge of the world is gleaned almost exclusively from the out of print pamphlets of Dobson, it comes as a crushing blow to learn that he was absolutely wrong, wrong, wrong in the matter of the mythical island o’ werewolves. You will recall that in his pamphlet The Mythical Island Where Werewolves Think They Come From (out of print), Dobson claims there is, within the brain of every werewolf, some sort of false memory nugget which throbs with the sights and sounds and smells of a wholly imaginary island. This, he says, is thought by all werewolves to be their homeland, to which they are driven to return, with an impulse as savage and unassuageable as their hunger for blood and guts. Hence the danger of docks and harbours, where werewolves roam, trying to stow away aboard ships and clippers and ocean liners.

You will also recall that in the 1956 film Bigger Than Life, James Mason, as cortisone-addled schoolteacher Ed Avery, declaims, as only James Mason could, the line “God was wrong!” Shocking that may have been to a 1950s audience, but how much more shocking is it, today, to utter the words, or even to entertain the thought, “Dobson was wrong!”? Yet, unbelievably, that indeed appears to be the case, according to a new study by jumped-up young Dobsonist Ted Cack. In five hundred pages of densely argued and pretty prose, the wet behind the ears little squirt pulls apart the pamphleteer’s pronouncements upon werewolves, demonstrating them to be complete drivel.

“Ah!” you may cry, “But what about all those footnotes?” It is true that The Mythical Island… is one of Dobson’s most heavily annotated works, bulging with an apparatus of footnotes and references and scholarly appendices. So bulky did all this stuff make the first edition of the pamphlet that, when running off the first few copies in the shed, Marigold Chew broke her Gestetner machine and had to call out a person from Porlock to repair it. That is why the additional material was published as a separate pamphlet thereafter, the pair of pamphlets bunged together into a cardboard box, to which was stuck with glue a mezzotint of a werewolf done by the noted mezzotintist Rex Tint. It is perhaps the most sought-after Dobson rarity coveted by collectors, which makes Ted Cack’s revelations all the more dispiriting.

What on earth can have made Dobson deceive his readers so? It is not a question Ted Cack tries to answer, but then he is young and callow and has not yet gained a proper apprehension of Man’s fallen state. The fruit of the tree of knowledge is not a fruit Ted Cack has bitten, yet. His time will come, as it does to us all, as it certainly did to Dobson.

Because the pimpled youngster does not address Dobson’s motives for churning out this screed of twaddle, we are forced to draw our own conclusions. For what it is worth, and despite the evidence piled up against him, I think it is legitimate to ask if Dobson actually believed the absurdities he wrote of werewolves. It would not be the first time he was subject to delusions, hallucinations, and general brainpan dislodgement. The critic Bernard Levin wrote of Beatleperson John Lennon that “there is nothing wrong with [him] that could not be cured by standing him upside down and shaking him gently until whatever is inside his head falls out.” The same was true of Dobson, if not more so. In fact, Marigold Chew designed, but never got round to building, a sort of hoist, of deal and wicker and gutta percha, into which the pamphleteer could be pinned, upended, and shaken about. Had such treatment been applied, perhaps on Thursday mornings, before breakfast, Dobson might never have cast so ineradicable a blot upon his reputation as The Mythical Island Where Werewolves Think They Come From.

So did he think it was true? Did he just wilfully misread all those quotations and references with which the pamphlet is packed? The problem here is that he seems to have invented most of his sources, from ancient texts in Latin and Greek and Ugric, to scripts from films and radio plays, and a paragraph about werewolves apparently copied down from the back of a carton of breakfast cereal. Tellingly, Dobson does not say what the cereal was, and in any case, the pamphlet was written at a time when we know he only ever ate bloaters for breakfast. Oh, it is a puzzle to be sure!

A clue may be found by close reading of his earlier werewolf pamphlet, The Hidden Wealth Of Werewolves (out of print), the one where he bangs on about werewolves living in caves wherein are kept toads in hanging cages, the toads having jewels embedded in their heads. It all sounds a bit unlikely, doesn’t it? Did he invent that, too? Ted Cack ignores this pamphlet completely, but then perhaps he has never heard of it. To gain a familiarity with the entire corpus of Dobson’s work takes years and years, as I know to my cost. And I have decades yet to live, God willing, before I am as ancient and craggy and stooped and wizened as Aloysius Nestingbird, the greatest Dobsonist of all, who is well into his second century and has collected several free bus passes from the government. He sells the spare ones on a website called Nestingbird-Bay, and spends the proceeds on gruel, which is all he is able to digest after long years of debauch.

The point about the first werewolf pamphlet is that Dobson always denied having written it. He claimed it was a forgery, wrought by sinister and shadowy associates of international woman of mystery Primrose Dent. If this is indeed the case, it would be a fool who would dare to investigate further. Let us not forget that the last person to probe the doings of La Belle Dent, a television reporter even more pimply and callow than Ted Cack, was pinned, upended, and shaken about in a hoist umpteen times more terrifying than Marigold Chew’s unrealised design. I am not joking. That is why I am going to stop writing about the whole confounded business, and go for a walk down by the docks, where I may or may not be set upon by marauding werewolves. And if I am, it will be a fate far less horrifying than Primrose Dent’s hoist.

Werewolf Tax

It is a wonder that, in all the talk of the nation’s parlous financial state and of the need to reduce the deficit, none of the main – or indeed minor – political parties has suggested one particular way of raising revenue. It has been left to economics guru Bingley Swelling to call for a werewolf tax.

In a paper presented to the Pointy Town Pointyhead think-tank last week, Professor Swelling outlined, with bullet points, some of the benefits of such a tax. There were three bullet points in total, of gold and silver and bronze, and it should be said that they were not made, literally, by firing bullets from a Mannlicher-Carcano sniper’s rifle à la Oswald, but represented by puncturing three holes in the Professor’s cardboard worksheet using a heavy duty hole-punch from Hubermann’s stationery department. The rim of each hole was then coloured accordingly with lead-based gold and silver and bronze paints applied with a long-handled Pastewick brush, of weaselhair. Beside the holes, or points, upon his cardboard, Swelling inked some text, with a biro, before propping the worksheet on a tubular metal display stand, for easy viewing by the think-tankists gathered to hear his… I was going to say “lecture”, but that does not quite give the flavour of the Swelling approach.

Not actually a werewolf himself, the Professor nonetheless had the appearance of one. If his yellow, bloodshot eyes, lumbering gait, and shocking hairiness were not enough, his speaking voice was akin to a lupine howl, whether the moon was full or otherwise. This made it hard to grasp what he was saying, hence the pedagogical aid of the cardboard worksheet with its bullet points. Thereagain, it would take a mind of infinite subtlety to interpret the hacking and stabbing marks made by the Swelling biro. His handwriting was atrocious, though in fairness, given the size and shape of his appendages, perhaps one should prefer the term paw-writing. Thus the paramount importance of the holes themselves, and the colours of their painted rims.

Here are some notes I took on the occasion. I hasten to add that I am not a paid-up Pointy Town Pointyhead, but I know how to worm my way into such meetings through bluffery and mesmerism.

“Gold. Werewolves often have enormous reserves of wealth in the form of precious stones hidden in caves. Sometimes these jewels are embedded in the heads of toads, the toads being kept in cages hung from the roofs of the caves. Source : The Hidden Wealth Of Werewolves by Dobson (out of print).

“Silver. Impossible to understand the first thing about this bullet point, other than the assertion that at least twenty billion could be raised “at a stroke”. But twenty billion what?

“Bronze. Swelling’s clincher. A one-off levy, set at a swingeing rate, on all werewolves waylaid when attempting to embark on ships sailing across the mighty oceans bound for the mythical “island o’ werewolves”. Source : The Mythical Island Where Werewolves Think They Come From by Dobson (out of print).”

Unlike the pointyheads, who were wild-eyed and nodding enthusiastically, I identified a number of problems with Professor Swelling’s thesis, not least his overreliance on out of print pamphlets by Dobson as intellectual ballast. Still, even I have to admit that there is much here to chew over, and chew over it I shall, just as a werewolf might gnaw one’s vitals having sunk its fangs into one’s throat, out on the moors, on a moonlit night.

Tiny, Lethal

Reading an item in yesterday’s Guardian about tiny lethal phantasmal poison frogs, I was reminded of Dobson’s pamphlet My Terrifying Encounter With A Tiny Lethal Phantasmal Poison Frog (out of print). It is by any measure one of his most exciting works, guaranteed to have one panting for breath and to cause beads of sweat to break out upon the brow. This is due to the pamphleteer deploying, as he so rarely did, his remarkable ability for building suspense. Alerted by the title, we are in a state of heightened expectation for the appearance of the minuscule killer, so tiny yet so toxic. But Dobson is in no hurry to come face to face with the lethal frog.

He begins by recounting, in exasperating detail, how, in preparing for a morning trudge along the towpath of the old canal, he discovered that the aglets on his Batavian Crimebusters’ boots had become rusted and brittle, the bootlaces fraying as a result. Reluctant to don a different pair of boots – for reasons he enumerates over five pages – Dobson describes his search, in drawers and cupboards and hideyholes, for a replacement pair of bootlaces. Throughout this “desperate fossicking”, as he calls it, Marigold Chew is staring out of the window at the incessant rainfall, picking out a tune on her celeste, composing in her head the words of the song that would later be known as The Ballad Of Incessant Rainfall.

In his monograph on Dobson’s various items of footwear, Aloysius Nestingbird asks why the pamphleteer did not simply remove the laces from one of his other pairs of boots and reuse them when it became obvious that he had no pristine bootlaces to hand. He answers his own question by delving into Dobson’s infamous pamphlet Every Lace Has Its Own Boot (out of print), the work which plumbed in excruciating detail the unfathomable depth of the pamphleteer’s neurosis in these matters. Those of us who have read our Nestingbird will have his commentary in the back of our minds as we follow Dobson crashing about the house on his futile search. Twenty pages in, we are no closer to our own encounter with the tiny lethal phantasmal poison frog, but the tension is becoming unbearable. At the point where Dobson describes tipping out onto the floor the contents of a battered cardboard box kept under the kitchen sink, we are ready to put the pamphlet aside and to put the kettle on for a calming cup of tea.

Next, we take a nap, and when we return to the pamphlet we find that is what Dobson did too. Giving up hope of finding new bootlaces for his Batavian Crimebusters’ boots, and leaving Marigold Chew plinking and musing and staring out of the window, the pamphleteer retires to his nap-hub. Now he cranks up the suspense by treating the reader to a detailed account of his period of unconsciousness, accompanied by masterly, if somewhat florid, descriptions of his pillows, his coverlet, and his mattress. Nestingbird has remarked that “no one has ever written about the nap as brilliantly as Dobson. The only wonder is that he never devoted an entire pamphlet to the subject.” This is uncharacteristically careless of Nestingbird, who has overlooked the mid-period pamphlet Fifty Pages Of Prose About Daytime Naps In Theory And Practice (out of print). It is an inexplicable lapse on the part of the greatest of Dobsonists, one I am minded to attribute to his habit, in later years, of mulch ‘n’ mop cloth bish bosh flossy flapping.

And so we are put on tenterhooks, still awaiting the terrifying encounter with the tiny lethal phantasmal poison frog, wondering if perhaps when Dobson wakes from his nap it will be to find the diminutive assassin perched within his bouffant. But no. He wakes, he grunts, he stumbles to his escritoire and begins scribbling. What we now come upon is not the fatal frog, but one of the central mysteries of Dobsonist scholarship. This is what the pamphleteer tells us:

I woke, I grunted, I stumbled to my escritoire, and thereupon scribbled ten pages of mighty prose, putting the finishing touches to my pamphlet Six More Lectures On Fruit.