Category Archives: Ice

BBC Weather

One of the BBC’s regular weather forecasters is Stav Danaos. This always sounds to me like a name from Game Of Thrones. One imagines Stav hanging out with, say, Stannis Baratheon or Daenerys Targaryen. That being so, it is somewhat puzzling that his weather forecasts do not consist simply of the words “winter is coming”, every day.

On Giant Albino Kangaroos

Over the past year or so in Miss Blossom Partridge’s Weekly Digest, Miss Blossom Partridge has been publishing a fascinating series entitled “Female Missionaries Of The Victorian And Edwardian Eras”. I was particularly enchanted by a recent piece on the Edwardian missionary Mrs Diphtheria Croak, and sought permission to repost it here – that permission being granted after I made a small donation to Miss Blossom Partridge’s Charitable Fund For The Relief Of Distressed And Destitute Bus Conductors’ Widows And Orphans (Penge). Read and enjoy!

One of the most venturesome of the female missionaries of the Victorian and Edwardian eras was Mrs Diphtheria Croak, widow of “Chippy” Croak, the one-legged country parson and amateur wrestler who went down with the Titanic. She did not accompany her husband on the fateful voyage, being, by her own account “paralysed with terror by the vast pitiless sea”. Yet within a few years of “Chippy”’s death, she was rarely to be found on land, plying the oceans aboard a series of liners and clippers and packet steamers. Eschewing the comforts of a cabin, she spent most of her time out on deck, scanning the waters day and night through her pince nez. Many thought that, unhinged by grief, she was searching for her lost husband. But that was not it. That was not it at all. Mrs Croak was in the grip of a mania, sure enough, but it was a mania of a different, and far stranger, kidney.

I first became aware of the existence of a colony of giant albino kangaroos, she wrote, when sorting through my late husband’s papers after his death. In among the drafts of sermons, newspaper cuttings of amateur wrestling bouts, and mad hysterical screeds scratched in ducks’ blood in an unknown alphabet, I chanced upon an article torn out of a periodical which made mention, inter alia, of giant albino kangaroos.

Immediately my heart went out to these poor benighted creatures. What kind of life must it be?, I wondered, to be gigantic and albino and to go hopping about like an abomination of nature? I determined at once to go among them, bringing succour and Christ, that they may know the Lord has abandoned none of his creation. But first I had to discover where they dwelt.

This was easier said than done, for Mrs Diphtheria Croak was a geographically obtuse woman who had absolutely no sense of direction. Often, leaving the country parsonage to buy eggs from a peasant who lived but a few yards away to the right, Mrs Croak would turn left out of her door and wander for hours, or days, eggless and ditsy. She had no understanding of the visible horizon, thinking there was something amiss with her eyesight, and demanding ever more powerful pince nez from her eye doctor.

Thus it was that she embarked upon her senseless series of sea voyages. Sooner or later, she reasoned, if she peered with sufficient intensity from the railings of an ocean-going vessel, she would spy land. She further reasoned that the albino kangaroos being giants, they ought to be easy to spot, hopping about in their abominable Godless fashion.

And so for seven years she sailed hither and yon, from continent to continent, port to port, keeping a lookout. In her reticule she kept several Bibles and a bag of millet, the latter a gift she intended to present to the leader of the giant albino kangaroos as a token of her goodwill. She was not sure kangaroos ate millet, but consoled herself with the idea that, if they did not, they could find some other use for it. Eventually she ended up eating it herself, to keep body and soul together when marooned for a month on a remote atoll following a maritime mishap.

Brrrr!, I said to myself one morning, it is very chilly and no mistake!, she wrote, This was seven years into my search, and to date I had seen no signs of the giant albino kangaroos. But I am a single-minded widow of great determination, and I knew in the very depths of my immortal soul that without me, the giant albino kangaroos would never bask in the magnificent effulgence of Christ Our Lord. It was quite impossible that I should abandon them. Now, as I leaned over the railings peering with great intensity into the distance, I saw enormous and forbidding cliffs of ice. No wonder it was chilly! A sailor was swabbing the deck nearby, so I asked him where we were. ‘That is the Antarctic, madam,’ he replied, ‘So you had better wrap up warm!’ I was glad he warned me, for when we made landfall some hours later it had grown colder still.

Some instinct must have told Mrs Croak she was, at last, on the right track, for with a dainty wave to the sailors she set off across the ice towards the enormous and forbidding cliffs.

Several years later, a ship landed at the same spot on the Antarctic coast. As the sailors played an impromptu game of ice hockey, they were astonished to see, emerging from the cold white expanse of nothingness, a country parson’s widow. She was carrying a reticule and peering at them through her pince nez. It was Mrs Diphtheria Croak.

“Might I board your ship and sail back to Blighty?” she asked, “My work here is done.”

And back in Blighty she wrote an account of her years in the Antarctic.

Nothing had prepared me for the look of joy on the faces of those giant albino kangaroos, she wrote, When I dinned into their big kangaroo heads the overwhelming love of Christ Jesus. Now when they hop about in their freezing ice-girt wasteland, it is no longer the hopping of Satan’s spawn. They hop for the Lord, who they see as a giant albino kangaroo much like themselves, only bigger and whiter. It is an image of Christ I have come to share, hence the somewhat unusual wood-carvings that keep me gainfully occupied and have become a feature of my country parsonage garden.

Mrs Croak died in 1934. Her wood-carvings were carted off by a rascally tinker. It is not known what became of them.

Snow-Covered Penguin

One Thousand

Today there is cause for celebration. No, not the Muggletonian Great Holiday, that was last week. The reason for unbridled cheer is that what you are reading is the one thousandth postage at Hooting Yard since the site was rejigged at the beginning of 2007. (I cannot recall precisely how many postages appeared in the old format, to be found in the 2003-2006 Archive, but if memory serves it is something in the region of 950.) A milestone to be celebrated, then – but how?

Ideally, you lot would cancel all other engagements, put your feet up, and spend the rest of the day rereading all one thousand postages, in chronological order, making notes in your jotter, pausing occasionally to stare out of the window as you mull over a particularly arresting item, and generally wallowing in the sheer Hooting Yardiness of it all. Always remember that a day devoted to Mr Key is never a wasted day. However, I am sensible enough to realise that most of you will have other things calling on your attention, such as feeding the hamster, waiting at the bus stop, smoking, genuflecting, pootling about, milking the cows, rummaging in the attic, taking your pills, repairing the fence down by the drainage ditch, tallying up the entries in your ledger, doing the dishes, spreading jam on bread, clutching at straws, embarking on a perilous journey downstream by kayak, grovelling in filth, putting the spuds on, intoning spells against the pestilence, mucking about, boiling your shirts, describing an arc parallel to the surface, dusting the mantelpiece, rekindling that lost love, chopping celery, going for gold, doing the odd bit of trepanning, squeezing out sponges, cutting up rough, vomiting, preening, polishing your shoon, checking the gutters, making hay while the sun shines, piling Ossa upon Pelion, folding your towels, voting with your feet, remembering a childhood idyll, splitting an atom, clocking in, lurking in the shrubbery, gathering your wits, burning an effigy, being Ringo Starr, toiling to no purpose, making whoopee, burgling the Watergate building, casting the runes, mesmerising a duck, emptying the bins, licking some stamps, darning a hole in your pippy bag, crunching numbers, thwacking a bluebottle, going rogue, distributing alms to paupers, looking shifty, holding out a glimmer of hope, pole-vaulting, caterwauling, playing pin-the-paper-to-the-cardboard, rinsing lettuce, closing the barn door, glorying in crime, sticking to the point, feeling off colour, pondering the ineffable, gargling, straining, wheedling, pining, flailing, and lying crumpled and woebegone and exhausted and hot-in-the-brain. You may have to do all of these or none, but in either case the chances are that you will be unable to devote your every waking hour to Hooting Yard, even though you yearn to do so. We shall have to come up with some other form of celebration.

It is at times like these a person’s thoughts turn to cake. It will have to be an enormous cake, to fit a thousand candles on to it. Think of all that burning wax!

I shall leave you with that thought, and press on. One could, of course, throw a party. Invite a thousand guests, and have each of them commit to memory, for party-piece recital, the text – or, as bespectacled postmodernist Jean-Pierre Obfusc would say, the discourse – of one Hooting Yard postage (including this one). The drawback to this otherwise fantastic scheme is that some postages run to thousands of words, whereas some, very occasionally, have been wholly pictorial, other than the title. Allocating all one thousand to the satisfaction of every single guest is a task fraught with difficulty, and is unlikely to be achieved without conflict and, indeed, fist-fights. Now, incidents of physical violence are not unknown among the readership. Even the surprisingly numerous Hooting Yard devotees of the Mennonite faith engage in punch-ups from time to time. Don’t even go there, as the airheads say. Taken all in all, I am not sure the party is such a good idea. Anyway, where would you fit so many people? They would not all fit into your chalet or hovel or well-appointed yet curiously pokey high-rise urban living pod, and rental fees for barns and disused aeroplane hangars have gone though the roof, according to what I have been reading in So You Want To Rent A Barn Or A Disused Aeroplane Hangar, Do You, Chum? magazine. (It’s interesting to note, by the way, that the late Harold Pinter was on the editorial advisory board of this threatening, sinister publication.)

Cake, burning wax, and party all proving prohibitive, what are we to do? Well, in extremis, one can always turn to Mrs Gubbins for some outré ideas. For once in her life, the octogenarian crone is not helping police with their inquiries, in spite of that dodgy business with the pile of mysteriously bleached bones and the trained vulture, and she is to be found snugly ensconced in an attic room at Haemoglobin Towers, furiously unravelling tea-cosies. Where once she did knit, now she unravels. By heck, there will be a glut in the used wool market by the time she is done! It is possible this is part of yet another criminal scheme, but if so it is one that is far too complicated for my puny and innocent brain. Best to ask no questions, and leave La Gubbins to her unravelling. I popped my head in to her sanctum, though, just to ask if she had any bright ideas for a Hooting Yard Thousandth Postage celebration. She looked up, fixed me with that unnerving gaze, like a blind person looking at a ghost, and pronounced the single word “Nobby”. Then she went back to her unravelling.

It was difficult to know what to make of this. The only Nobby that sprang to mind was Nobby Stiles, the popular Manchester United and England midfielder of the 1960s. His joyous capering on the pitch after England hoisted the Jules Rimet trophy in 1966 had captured the imagination of the press in those more seemly times, so perhaps that was what Mrs Gubbins was recommending – joyous capering on a field of grass. Or was she suggesting that I should enlist Nobby Stiles to help with planning a celebration? It seemed unlikely, though not of course impossible, that the retired footballer was a Hooting Yard fan, but even if he was, I did not know him, had never even collected his autograph when I was a tot, and had no idea how to get in touch with him. I entertained the thought that perhaps the crone had said “knobby”, with a K, meaning that which is characterised by having knobs, or the quality of knobbiness, such as, for example, a gnarled tree-trunk, or the backs of certain kinds of toad, but that seemed even more unfathomable. La Gubbins being the kind of woman she is, it is likely that her pronouncement was a sweeping one, containing all possible meanings of “(k)nobby”, with and without a K, plus additional meanings thus far unrevealed to the common timber of humanity. But I am afraid I had to dismiss, as wildly impractical, the idea of getting Nobby Stiles, and perhaps some other lesser-known Nobbys, to assist me in arranging a celebratory caper, of people and toads, round and round a tree in a field, much as it was appealing.

It was back to square one, and as we all know, deep in our hearts, the question always to be asked at square one is “What would Dobson do?” The beauty of the question is that if we are able to arrive at a half-way sensible answer, we know the guidance given will be infallible. Working out a valid Dobsonian response, however, is to blunder along a path strewn with nettles and serpents, unless of course one is satisfied with the generic answer “Write a pamphlet!”, which is, admittedly, correct ninety-nine times out of a hundred. Even in the present case, I can think of few methods of celebration more apposite than that every one of my readers should sit down at their nearest escritoire and pen a pamphlet. But think of the logistics. Someone would have to collate all the screeds, typeset them, print them, and distribute them to an uncaring world. I try my best to retain an attitude of breezy optimism, but I cannot see it happening. And I have not seen any vans driving past recently announcing, from the lettering on their sides, that they are in the business of Pamphleteering Solutions.

But “Write a pamphlet!” is not, invariably, the answer to the question “What would Dobson do?” Very, very occasionally, by deep analysis of the question, exercising the brainpans to their fullest extent and beyond, a different answer is revealed. To find out what this is we need to have an encyclopaedic knowledge of the complete Dobson canon, and to have pieced together as much biographical information on the out of print pamphleteer as we can, not excluding rumour, hearsay, tavern mutterings, and wild surmise. That is why I put the question to Aloysius Nestingbird, who knows more about Dobson than anyone else alive. As it happens, Nestingbird is only barely alive, following a calamitous bobsleigh accident. Quite what a frail ninety-two-year-old was doing plunging down the Caspar Badrutt Memorial Perilous Ice Declivity at the Pointy Town Antarcticorama is a question for the bigwigs at the Fédération Internationale de Bobsleigh et de Tobogganing, who I understand have already empanelled a Board of Geriatric Investigation to be headed by the fiercely independent, because ignorant of bobsleigh matters in general, Ant, or it might be Dec, the taller of the pair, the one with the glassy eyes of death.

Anyway, I bluffed my way into the clinic where Nestingbird languishes, using the techniques prescribed by Blötzmann in his Methods Of Dissimulation To Be Employed When Entering Restricted Medical Facilities (Second Series), an invaluable work which I always carry with me, just in case. Nestingbird was almost invisible beneath a panoply of tubes and wires and monitors and bleepers and what have you, but I ripped them out of my way and put my mouth to his still-bloody, gored ear, and put to him, in a dulcet whisper, the question. I want to arrange a celebration of the thousandth Hooting Yard postage. What would Dobson do? Nestingbird groaned, and some sort of despicable fluid bubbled out between his bloody lips, but he managed to tell me the answer, albeit in a croak so weak I barely heard it. But hear it I did. He said “Nobby”.

Returning home via the funicular railway, I racked my brains to see if I could wring any sense from this. Put in my position, it appeared, Dobson would “do Nobby”, or, I suppose, “do a Nobby”, as if that made any difference. Neither was a phrase I had ever heard before, and nor had any of my fellow-passengers, whom I badgered about it, growing, I am ashamed to say, rather hysterical, to the point where I was bundled off the train as soon as it reached the base station and taken round the corner, past snow-covered shrubbery, and handed over to Detective Captain Cargpan and his toughs. It is lucky for me that Cargpan is a fanatical devotee of Hooting Yard, otherwise I feel certain I would have ended up back in the clinic, and in a much worse state than Aloysius Nestingbird. Instead, the doughty copper let me off with a mussing of my tremendous bouffant. He didn’t know what “doing Nobby” was, either.

I had the sinking feeling that if I sought advice from anybody else, from born-again beatnik poet Dennis Beerpint, for example, or from Old Farmer Frack, I would get the same response. When I eventually arrived home, I made a cup of tea and heated a couple of smokers’ poptarts. Perhaps the celebration would have to wait upon the two-thousandth postage. Or perhaps I should be grateful for my simple snack. I sat down at the table, slurped the tea and shovelled down the bitter poptarts. Was this, after all, “doing Nobby”?

Laundry Bag Boy

I have never been a fan of comic books, nor have I developed a taste for graphic novels. I can admire the skill and inventiveness, but somehow I can’t drum up genuine enthusiasm. Of course, as a child, I had my weekly diet of comics, including Pipsy Papsy, Factorum Et Dictorum Memorabilium, and The Dinky, but when I discovered proper books I was smitten by prose, and there was no turning back.

Until last week, that is, when I discovered a fantastic comic featuring the cartoon superhero Laundry Bag Boy. I have to admit it has been a revelation, and I am smitten all over again, this time by crude and cack-handed drawings and by storylines which have surely been devised by a dribbling toddler. Yet there is a majestic genius about Laundry Bag Boy, his adventures, his scrapes, his pratfalls, his laundry bag, that I find irresistible. The comic I picked up, absent-mindedly, from where it had been discarded on a bench under a sycamore by a path in a park, was fat and dog-eared and threatened by rainfall. I thought no more than to carry it to the nearest municipal waste bin and consign it to oblivion, but the waste bins had been commandeered by an avant garde arts project organised by a man called Simon, whose name was Peter, just like one of the apostles of Christ. But whereas the apostles were, as Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891) observed, “illiterate half-starved visionaries in some dark corner of a Graeco-Syrian slumâ€, the artist Simon and his pals were goatee-bearded trendies from Shoreditch destined to rot in hell. Before they rotted, they had filled all the municipal waste bins in the park with some kind of compacted orange substance, hard as concrete, rendering the bins unusable. According to leaflets available from a temporary kiosk, this “art intervention†was a “courageous statement about

Issue 10, Volume 34 of Laundry Bag Boy contained a couple of short strips about Douglas The Pig, who was, I learned, Laundry Bag Boy’s pet pig, and a few pages of adverts and promotions for other publications. The bulk of the comic, however, was a single full-length comic strip adventure called Laundry Bag Boy : The Shakatak Years. Now, just as in my adulthood I have never been a comics buff, nor have I ever cared much, or at all, for Shakatak, the British jazz-funk band who had hits in the 1980s with “Night Birds†and “Down On The Streetâ€, among others. Frankly, their smooth pap left me cold when first I heard it, and still does, two decades on. Readers who disagree with me, and who wish to champion the music of Shakatak and show me the error of my ways, are invited to argue their case in the Comments, but I will only pay attention to contributions which shake me to the core and force me to reassess my entire Weltanschauung. Those are the stakes. Be very careful before you tap that keyboard and hit “Sendâ€.

The plot of the story, such as it is, posits that for a period of seven years – precisely which years are maddeningly unspecified – Laundry Bag Boy acts as a kind of familiar to the dull as ditchwater jazz-funksters. They remain unaware of his presence, but he is always there, haunting them, watching over them, in a patch of shadow on stage or perched up in the rafters of the recording studio, breathing softly, clutching his laundry bag, which is sometimes empty but more often about two-thirds full of filthy unmentionables long overdue for the washing machine. With his yellow hair and blazing eyes, we, the readers, can always spot the superhero, but to the Shakatak personnel, including roadies, sound engineers and hangers-on, he might as well be invisible. You may wonder why none of them smell the pong emanating from his laundry bag, at times when it is about two-thirds full. This is because one of Laundry Bag Boy’s superpowers is an ability to pluck from the empty air a canister of air freshener and spray the contents of his noisome bag until it smells of roses and honey and lavender and poppy coral and citrus mango and pumpkin and neutradol and peach and apple and one other fragrance the name of which I cannot be bothered to look up right at this minute. More than one critic, reviewing a Shakatak concert, is claimed to have dubbed them the sweetest-smelling band in the world, although whether this really happened, outside the pages of the comic book, is not something I am competent to assert or deny, for I don’t care one way or the other. I am less interested in Shakatak than in Laundry Bag Boy himself. I have read mountains of prose in my time, books upon books upon books, but never have I fallen so deeply under the spell of a fictitious being. Despite looking, from some angles, like an incompetent portrait of the columnist Peter Hitchens, Laundry Bag Boy, with his aforementioned yellow hair and blazing eyes, and his pet pig Douglas, and his conjured-up air fresheners, and his laundry bag, stands, in my view, above the heads of Emma Bovary or Oscar Crease or Sancho Panza or Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, or Hans Castorp or Molly Bloom or Murphy or Molloy or Malone or Tyrone Slothrop or Doctor Slop or the Widow Wadman or Ishmael or Ahab or Pangloss or Percival Bartlebooth or Bartleby, the scrivener, or Trilby or Svengali or Hazel Blears or Gregor Samsa or Don Fabrizio Corbera, Prince of Salina, or Batman or Robin, The Boy Wonder, or Robin Hood or Humphrey Clinker or Pip or Magwitch or Geoffrey Firmin or Asenath Waite or the Mad Arab Abdul Alhazred or Pinkie Brown or Charles Swann or Quentin Durward or Martin Chuzzlewit or Fu Manchu or thousands of other fictional characters. He is a true superhero, and yet has a humanity that is palpable. Not literally palpable, of course, that would be stretching my enthusiasm too far, but figuratively, or so I would aver, and had already averred, during that very first skim reading, sheltering from the rain under the ruined bandstand in the park, as I became transfixed by the adventures of Laundry Bag Boy’s Shakatak Years.

When I got home, I reread the comic with closer attention, three or four times I think. I learned more about Laundry Bag Boy, that he had many more superpowers, and ones that made the air freshener thing seem like a party trick. He could, for example, meld his brainwaves with those of

I soon learned that such a sky is a constant throughout the canon, for I was so enthused by The Shakatak Years that I took myself off to a specialist supplier of comic books and bought as many other Laundry Bag Boy titles as I could fit into my own, non-laundry, bag. Regrettably, most if not quite all of the stories had a subplot related in some way to jazz funk, though not specifically to Shakatak, and yet this did not dim my glee. I deduced that either the writer or the artist, neither of whose names appeared in any of the comics as far as I could see, was a devotee of that devilish music, and lacked the self-control to expunge their aberrant leanings from the otherwise stupendous stories. Yet how often we forgive writers and artists for what are, after all, minor irritants. For example, I have never been able to stomach Dennis Beerpint’s infuriating habit of conflating dishcloths with other kinds of rags and sponges, yet I am still able to enjoy his verse for its vigour and punctilio. I feel the same about Laundry Bag Boy, much as I might wish that William Hurlstone’s Bassoon Sonata, say, could stand as a substitute for True Colours by Level 42.

Another thing I have noticed about Laundry Bag Boy is that he never blinks. This may be a limitation of the cartoon strip medium, or it may be that his eyes are übereyes, piercing and all-seeing and never for a moment at rest. And there is a lot for him to look at. Although the quality of the drawing is scrappy and fumbled, occasionally looking as if created by a cretin on a damaged Etch-A-Sketch, throughout the series there is an incredible amount of detail. The sky may be shown as flat and birdless and cloudless, but everywhere else in these pictures is a magnificent clutter of things. To take a picture at random, consider the opening frame from Laundry Bag Boy Gets Into The Groove With Herbie Hancock (Issue 4, Volume 28). Examining this with a Winckelmannscope reveals, in a rectangle taking up half the page, potatoes, bloaters, the weirdstone of Brisingamen, fourteen owls, dental floss diagrams, cotton, pins, pork rind, fur balls, rotating things, custard, muck, shoelaces, coat-hangers, an aerodrome, flame retardant fabric samples, snappy-cap tin cans, a glazed bowl, a Viking helmet, a syrinx, a rickshaw, geese, pots and pans, Edvard Shevardnadze’s golden tooth mug, bunsen burners and other burners, a tea strainer, a fencepost, gravel, cloth, sand, effluvium, ectoplasm, railings, a Brothers Johnson compilation compact disc, basil, hornets, dust, tweaking mechanisms, a pail of lugworms, a dictaphone belt, sandpaper, grimy unpleasantness, winches and pulleys, talcum powder, country and western paraphernalia, lozenges, screwdrivers, shredded wheat, box cutters, Basho trug holders, shipping timetables, phosphorescence, a spider’s web, a fountain pen, mysterious hat-like objects which are not hats, a basin, a dimity scrap, a bathtub, a shoe tree, a bee, an ice bucket, an immortal, a puppet crow with one button eye dangling loose, a puppet cow, a tap and an outside spigot, a copy of The Protocols Of The Elders Of Pointy Town, dubbin, flock wallpaper, old man’s beard, Mary Westmacott’s cot, hinges, blubber, fruit, clamps, sugar, goo, pond life, a desk sergeant, a calendar, litmus paper, an Unanugu jumper (darned), salivating weasels, snapping turtles, basalt, tonic water, goat pens, hacks and traps and charabancs, Wolfe Tone’s death mask, an earwig, a selection of different berries ready for the crusher, and the berry crusher, and another crusher, and yet other crushers, and crushers galore. It really is extraordinarily packed with detail. Laundry Bag Boy himself does not appear in this opening frame of the cartoon, and nor does Herbie Hancock. Their absence at the beginning is a crucial part of the plot, but I will not spoil it for you by explaining why.

While I was buying up back numbers in the comics shop, I took the opportunity to pump the proprietor for more information about Laundry Bag Boy. Intriguingly, the shop was run not by a geeky nerdy nerd geek, the kind we tend to associate with such establishments, but by a batty crone with a Quakerly air about her. Her hair was white and wild and she had a decided plum in her mouth. She was kind enough to offer me, from a somewhat battered tin, a choice of arrowroot and Garibaldi biscuits to munch while I browsed the cardboard boxes packed with comics. Unlikely as it seemed, she knew everything there was to know about my new-found fictional hero, a walking encyclopaedia of Laundry Bag Boy lore and learning, arcana and imponderabilities, facts and figures. One thing she told me in particular had me quite perplexed. In spite of the popularity of the yellow-haired, blazing-eyed superhero, there was no official worldwide fan club to which I could apply. This seemed anomalous, when there are such organisations devoted to virtually everyone you can think of, from fictional detectives such as Sherlock Holmes and Solar Pons, to real detectives like Sir Ian Blair and Cargpan of the Yard, from Sir Granville Bantock to Rock Hudson, from Lascelles Abercrombie to Spiderman, from Mike Huckabee to Ayn Rand, from Brutus Maximus to Popeye, from Arianna Huffington to Ringo Starr, from Krishnan Guru-Murthy to Tuesday Weld. Yet in this seething maelstrom of often ill-advised fandom, there was an unfathomable void where Laundry Bag Boy ought to have been.

I have decided to correct this preposterous state of affairs. Tomorrow, at

NB :Â Please check the Comments on this piece, for a particularly enlightening contribution from reader Randi Mooney.

Blodgett And Trubshaw

Blodgett had a certain militaristic cast to his character, so when he was given command of a pocket battleship it was understandable that he got slightly carried away. He fretted and fussed over his epaulettes and other trimmings of his uniform to a somewhat embarrassing degree, so much so that he neglected more critical aspects of his duty such as keeping a proper log. Thus it is that we do not have a reliable record of his one and only voyage.

This was a time of gunboat diplomacy, and Blodgett’s mission was to anchor his ship in a faraway bay, train his guns on the coast, and to threaten to blow the township there to smithereens unless certain conditions were met. All very straightforward, or it would have been had the ship not had for its navigator a man who had lost his wits. This fellow’s name was Trubshaw, and it is a wonder that he still had the confidence of the Admiralty, for he had been bonkers for years. Instead of steering the ship towards the faraway bay, Trubshaw pored over his charts and barked instructions through a pneumatic funnel that led to the ship becoming encased in pack ice thousands of nautical miles away from its proper destination. There was no township upon which to train the guns, leaving Blodgett at a loss what to do, other than to preen his epaulettes and other trimmings with a little brush.

Trubshaw, meanwhile, was following his own demented star. He took to pacing up and down the poop deck shouting at the sky. Icicles formed on the brim of his navigator’s cap, but he seemed impervious to the cold. Not so the rest of the crew, huddled below decks wrapped in blankets and keeping their spirits up by playing board games and eating sausages. Blodgett kept to his cabin, using his log as a pad for doodling. He had lost radio contact with the Admiralty weeks ago. There was nothing for it but to sit the winter out and wait for the ice to melt.

At this point, I expect the majority of readers will be avid for further details of the board games and the sausages, and I will not disappoint. However, before dealing with those crucial topics, perhaps it is wise to say a few more words about Trubshaw. His insanity was not in doubt, but what has never been established is whether he deliberately stranded the ship in Antarctic waters, or whether within the vaporous murk of his mad brain he honestly believed the ship was heading for that faraway bay. There may be a clue in the words he was shouting at the sky while pacing the poop deck, and by chance we do have a record, albeit fragmentary, of what they were, or some of them at least. By chance an airship packed to the gills with the very latest magnetic cylinder recording technology passed overhead one day, and some of Trubshaw’s shouting was picked up by its monitors and etched onto a cylinder, preserved forever. If you get a special coupon for entry to the sound recordings rooms of the Museum At-Or-Near-Ack-On-The-Vug, you can listen to this bewildering caterwaul. Dobson once planned a pamphlet on Blodgett’s voyage, and transcribed part of Trubshaw’s tirade, but abandoned the essay in favour of his justly famous Bilgewater Elegies. Thanks to Dobson, though, we can reprint the shouting, and gain an eerie insight into the crackbrained navigator pacing the poop deck of that ice-girt pocket battleship so many, many years ago.

“Wheat! Bulgar wheat!†begins the Dobson transcription, “Wheat and gravel and sand and grit! Powdered paste! Paste in puddles! Gravel and sand a-criminy! Pitch and tar and globules of black, black, blackened goo! Cracking pods squelching underfoot! Pods of ooze and glue! Pitted black olives in a jar, pitted and black like a black pit! Cracked bulgar wheat and cracking sand! Black pudding! Vinegar down your throat! Malt and muck underfoot in vast paste puddles of goo!â€

It is difficult to know precisely what to make of this, except to conclude that Trubshaw was completely off his head and that, charts and barked instructions to the crew notwithstanding, navigation was not uppermost in his mind. That being so, we can get on to the more diverting business of the board games and the sausages, as promised.

The ship’s cook was a follower of the dietary theories of Canspic Ougat, and that being the case there was little if any animal flesh in his sausages. One might, when munching, occasionally sink one’s teeth into a fragment of pig or goat or starling, but only a tiny fragment, often so tiny as to go unnoticed. The cook made his sausages from an Ougat-approved compaction of mashed up turnips and marshland reeds and grasses, leavened with some sort of secret curd. They came in two sizes, jumbo and cocktail, although the latter were not served on cocktail sticks due to Ougat’s stern prohibition of sausage-piercing. Holes, even the very wee ones made by the average cocktail stick, were anathema to the dietician, for reasons propounded in the preface to his magisterial Codex Sausageiana. Even if you are not particularly interested in sausages, this book is a fantastic read, and I cannot recommend it too enthusiastically. I try to read a few paragraphs every day, much as some people dip daily into the Bible, or into Prudence Foxglove’s Winsome Thoughts For The Dull-Witted. Much of the ship’s cargo hold was occupied by the cook’s crates of sausage ingredients, and he was forever puffing and blustering about his galley, kneading the turnip and marshland reeds and grasses and secret curd and occasional bits of pig and goat and starling into the sausages in which he took such pride, inspecting every single one with a powerful microscope to ensure that it was free of even the most minuscule hole. And of course, the crew gobbled them down greedily at mealtimes, both jumbo and cocktail varieties, for they had nothing else to eat. That’s quite enough about sausages.

Blodgett had made it a condition of his command of the pocket battleship that it be stocked with lots and lots of board games. And so three entire cupboards below the orlop deck were stacked with them, from family favourites such as Plutocrat!, Dentist’s Potting Shed and To The Finland Station to more obscure games like Treat The Dropsy With Leeches, Butcher’s Shop Railings, and Fictional Athlete Bobnit Tivol Cement Running Track Challenge Cup Heat Four. On the rare occasions he popped his head into the cabin where the crew huddled together for warmth through that freezing polar winter, Blodgett was always pleased to see that they were kept fully occupied by one board game or another. The gang of sailcloth patchers took particular pleasure in Patch That Sail!, a fast and furious yet at times slow-moving game involving equal measures of cunning and luck. The board itself represented a piece of sailcloth, and indeed was made of sailcloth, and the players took it in turns, by throwing dice and moving their counters, to patch up the various rips and rents in the cloth with needle and thread. Meanwhile, over in one corner of the cabin, Blodgett was sure to find the crows’ nest men playing a sprightly game of Groaning Widow, a contest so fiendishly complicated that only the superior brainpans of the crows’ nest men had a chance of understanding it. Other, less bright sailors would watch, gawping, for hours, as counters flew around the board, spinners were spun, card-packs consulted, and little plasticine models of characters from The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann were put in place, knocked over, taken to pieces, remodelled, repainted, and had the heads pulled off them and substituted with special bonus tokens. Only a fresh pan of sausages from the galley would interrupt the crows’ nest men’s concentration, when they would sulkily take a break to feed, having taken snapshots of the board from several different angles to prevent cheating.

And so the winter wore on, until one day the ice melted away and the pocket battleship sailed home. Trubshaw had abandoned ship by this time, stomping off across the ice floes in curiously subdued fashion, no longer shouting at the sky, his face barely visible behind the thick row of icicles dangling from the brim of his cap, stooping occasionally to pluck some kind of primitive edible life form from the cold, cold sea with his fur-bemittened fist. Blodgett watched from the prow of the battleship as his navigator vanished into the white nothingness. Weeks later, they began the return voyage, guided by the stars, which one of the crows’ nest men knew how to read.

Blodgett was of course hauled before an Admiralty Star Chamber to account for himself. Why had he failed to sail to the faraway bay for a spot of gung ho gunboat diplomacy? He burbled and babbled and preened his epaulettes and other trimmings, but at no point did he ever mention Trubshaw. He had even expunged the navigator’s name from the list of crew pinned up on a post at the entrance to the Star Chamber, and inevitably there was no reference to Trubshaw in Blodgett’s hopelessly inadequate captain’s log. Which, I suppose, begs the question: did Trubshaw ever actually exist? Or was he a wraith or phantom, or even a ghoul, of the kind known to haunt ships of the line as they ply the oceans, sailing round and round and round, into the maelstrom?

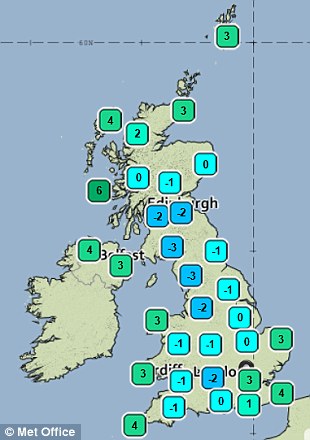

Ice Chaos

[This story was written as part of a fundraising drive for ResonanceFM, and broadcast today on Hooting Yard On The Air. Listeners were invited, in return for a donation, to provide a sentence, a phrase, a string of words or a name which was then incorporated into the text. A list of those who so generously handed over their cash follows at the end.]

Now, it has been pointed out to me more than once that I am hardly qualified to talk about extreme weather conditions, as the only weather we get at Hooting Yard is rain, sometimes torrential, sometimes a drizzle, and this is true. What my critics fail to note is that, ensconced in a cabin somewhere over by Blister Lane Bypass, we have a superb forecaster. I speak, of course, of Little Severin, the Mystic Badger. When it comes to predicting the weather, Little Severin is second to none, not even to the BBC’s magnificent Dan Corbett. If you have not watched Dan, visit That’s The Weather For Now and be amazed. Little Severin the Mystic Badger has not yet been blessed with a fan site all his own, but it can only be a matter of time.

Before we go on, I want to make it absolutely plain that there is neither a jot nor scintilla of truth in the rumours that have been flying around. Little Severin did not pass through the catflap to the afterlife. In any case, he would have eschewed a catflap and sought a more appropriate badgerflap. Flaps for badgers, and indeed for stoats, pigs, wild hogs, otters and curlews, some of which are flaps to the afterlife and some not, are easily available, for example from Zip Nolan’s Flappery in Basoonclotshire. (That spelling is correct, as the name of the shire derives from basins, not from bassoons.)

Little Severin’s method of weather divination is simple yet brilliant. He is not known as the Mystic Badger for nothing. At various times of day or night, he emerges from his cabin and scrubbles around in the muck, like badgers do. Then he goes back indoors. Voila! Those able to read the omens and portents of his scrubbling know whether tomorrow will bring rain, downpour, or drizzle, and not only that, for Little Severin can predict more than just the weather. Few people are aware that he forecast both the Cod Wars between

It is the mysticism which so upset Braithwaite, the one-time bus-seat companion of Clytemnestra Duggleby. It was Braithwaite, with his pipe, his face, his cheese, his keys, his rissoles, his cup, his roll-on-roll-off rim-fire thiamin, and that lip on him, the lip and the sculptured boy-hair, Braithwaite who called into question the accuracy of Little Severin the Mystic Badger’s paw-scrubbling weather forecasts. But what did he know? As Clytemnestra Duggleby attested in court after the incident with the wheezing scrivener and the invalid postscript font, he spent most of his time slumped in front of the radio, like some antediluvian beast, listening distractedly to The Sagans, (or Les Sagans) a long-running serial about husband-and-wife team Carl and Françoise and their thrills, spills, window sills and gas bills as they bring up their papoose Boo Boo. The show’s theme tune features the papoose Boo Boo singing “Meinen Mootzenzimmer†backed by an orchestra of massed banjos and ducks with electronic implants. Clytemnestra hated the drama, but adored the music, and hummed it as she went about her many and various janitorial doings in the town aquarium. It was a submerged aquarium, hewn out of the geological strata underneath the abandoned zoo, and it was rife with weird tentacled aquatic beings (actual size) including squid. According to the aquarium guidebook, “Squids are mammals, just like plants and cloudsâ€, for the book had been compiled by Zip Nolan (he of the Flappery) in a break from writing his pot-boiler series of animal-flap related thrillers such as Creepy Raoul And The Partridgeflap, Creepy Raoul And The Beeflap (serialised in Harpy magazine), and the million-selling Creepy Raoul And The Ineffable Mystery Of The Pentecostalist Cormorantflap, which famously begins “Rendered placid by the sickening stifle, this cumbersome vision of Britney lolled like some spastic hound, a revolutionary Lolita trying in vain to calm my wayward reflexesâ€. Quite why Zip accepted the commission to compile the guidebook is as much a mystery as one of his thrillers, for he was no lover of waterworld – and I am not talking about the Kevin Costner film. Zip was a dry land sort of person, so much so that he avoided ponds and puddles, and made daily treks all the way from his Flappery in Basoonclotshire to consult with Little Severin The Mystic Badger about the weather, the weather, the weather.

[Those who donated money to help save ResonanceFM, and whose suggested words appear in “Ice Chaos†are, in alphabetical order: Pansy Cradledew, William English (on behalf of Fotheringay), C J Halo Goat Luncheon (anagram), aka John ‘Alcohol Nut’ Cage (also an anagram), Sandra Harris,

NOTE : The episode of Hooting Yard On The Air including this story has been given an early podcast release. Go to the podcast archive to listen or download.