Blodgett (wearing a wig) surprises Mrs Pepinstow in her boudoir. But who is the mysterious figure looming in the background?

Category Archives: Blodgett

Blodgett’s Diary 24.1.46

Blodgett’s diary for this day in 1946:

Pucker crunched duct. Hod tap askew, righted, fumbled. Pit gawped ope, shoved funnel up. Tawny pipit stuck w/ birdlime to spruce. Gnarled bole. Hacksaw honed, whetstone cracked. Figs in punnet. Jug on sill caught light ‘n’ odd, flat ant. Modern barber called. Chopped at tresses and flicked flecked highlit strands. Infected cow udder. Crumpled rag in bin. Bin beside sink. Barbaric gusts. Lemsip. Kite in ash. Go-go dancer in boat on lake in twilight. Noggin puttered. Putter slack. Gutta percha in gunny sack. Milk spilt, night soil sloshed. Stove exploded. Hooves clattered. Dots pricked. Gummed up shrift. Go to work on an egg.

On Astrology

Eight years and one month ago, I posted the following horoscope here at Hooting Yard:

Our horoscopes are based on the so-called Blodgett Astrological System of six, rather than twelve, signs. Over many years, forecasts made under this system have proved over eight hundred and forty-eight times more reliable than all that Pisces and Aquarius nonsense! You can work out which sign you are by referring to the absolutely splendid up to date online guide at www.blodgettglobaldomination.com/humanfate.html (site under construction).

Fruitbat. Try to remember that you are lactose-intolerant. The hours before twilight will be significant for your pet stoat. Throw away that tub of swarfega.

Mayonnaise. It is time to dig out your copy of Gordon “Sting” Sumner’s profound I Hope The Russians Love Their Children Too and play it again after all these years. You may overhear the phrase “going postal” more than once this afternoon. Pay special attention to patches of bracken.

Coathanger. Your recurrent nightmares about an albino hen will finally make sense. Don’t go near any buildings, large or small.

Slot. At last your destiny will begin to unfold, probably as you take a stroll along the towpath of the old canal. Vengeful thoughts will assail your brain, but you should ignore them, and devote your energies to making jam. A hollyhock may have special meaning for your kith and kin.

Tarboosh. O what can ail thee, horoscope reader, alone and palely loitering? Make sure you treat yourself to an electric bath and a session in a sensory deprivation tank. The Bale of Gas in your House of Stupidity has incalculable effects. You will stand on the steps of the Insane Asylum, and hundreds of men and women will stand below you, with their upturned faces. Among them will be old men crushed by sorrow, and old men ruined by vice; aged women with faces that seemed to plead for pity, women that make you shrink from their unwomanly gaze; lion-like young men, made for heroes but caught in the devil’s trap and changed into beasts; and boys whose looks show that sin has already stamped them with its foul insignia, and burned into their souls the shame which is to be one of the elements of its eternal punishment. A less impressible person than you would feel moved at the sight of that throng of bruised and broken creatures. A hymn will be read, and when the preachers strike up an old tune, voice after voice will join in the melody until it swells into a mighty volume of sacred song. You will notice that the faces of many are wet with tears, and there will be an indescribable pathos in their voices. The pitying God, amid the rapturous hallelujahs of the heavenly hosts, shall bend to listen to the music of these broken harps.

Nixon. Vile dribbling goblins covered in boils will make life difficult today.

Why am I returning to this old horoscope today?, you may ask. Well, for eight years I have been ignoring a cardboard box full of letters which I received in the days after this postage appeared. The box – or rather its contents – gnawed at my conscience. Gnaw, gnaw, gnaw. I have had a terrible time. If you have ever felt reproached by sight of a cardboard box, you will understand what I have been going through. That is why I hid the box in a cubby and buried it beneath a pile of rags and locked the cubby and took a bus to the seaside and hurled the key as far as I could into the broiling ocean. I thought, by doing so, I could put those letters out of mind. How could I be so naïve?

After a near decade of mental turmoil, yesterday I called a locksmith and asked him to fashion a fresh key for the cubby. With commendable honesty, given that he was turning down my custom, he pointed out that the cubby door was of so flimsy a nature that even a puny person could bash it open as easily as smashing an egg. Watch, he said. And he gave the door a thump and it fell to bits and there was the pile or rags and, beneath, the cardboard box, and, in the box, the letters.

I plucked from the box the first one that came to hand, and read it. Eight years had passed, but I remembered every word.

Dear Mr Key

I am writing to complain about the horoscope you posted at Hooting Yard yesterday. I was born under the sign of Coathanger, so I was fully expecting my nightmares about an albino hen to make some sort of sense. I so arranged things that I spent the day in an eerie blasted landscape of marshes and moorland, far, oh so far, from any buildings. I awaited revelation, but revelation came there none. I can only conclude that your so-called horoscope is a piece of piffle. You have ruined my life. I am going to take my case to the Astrological Courts, and you will be prosecuted, and all your stars will be blotted out, forever!

Yours vengefully,

Tim Thurn

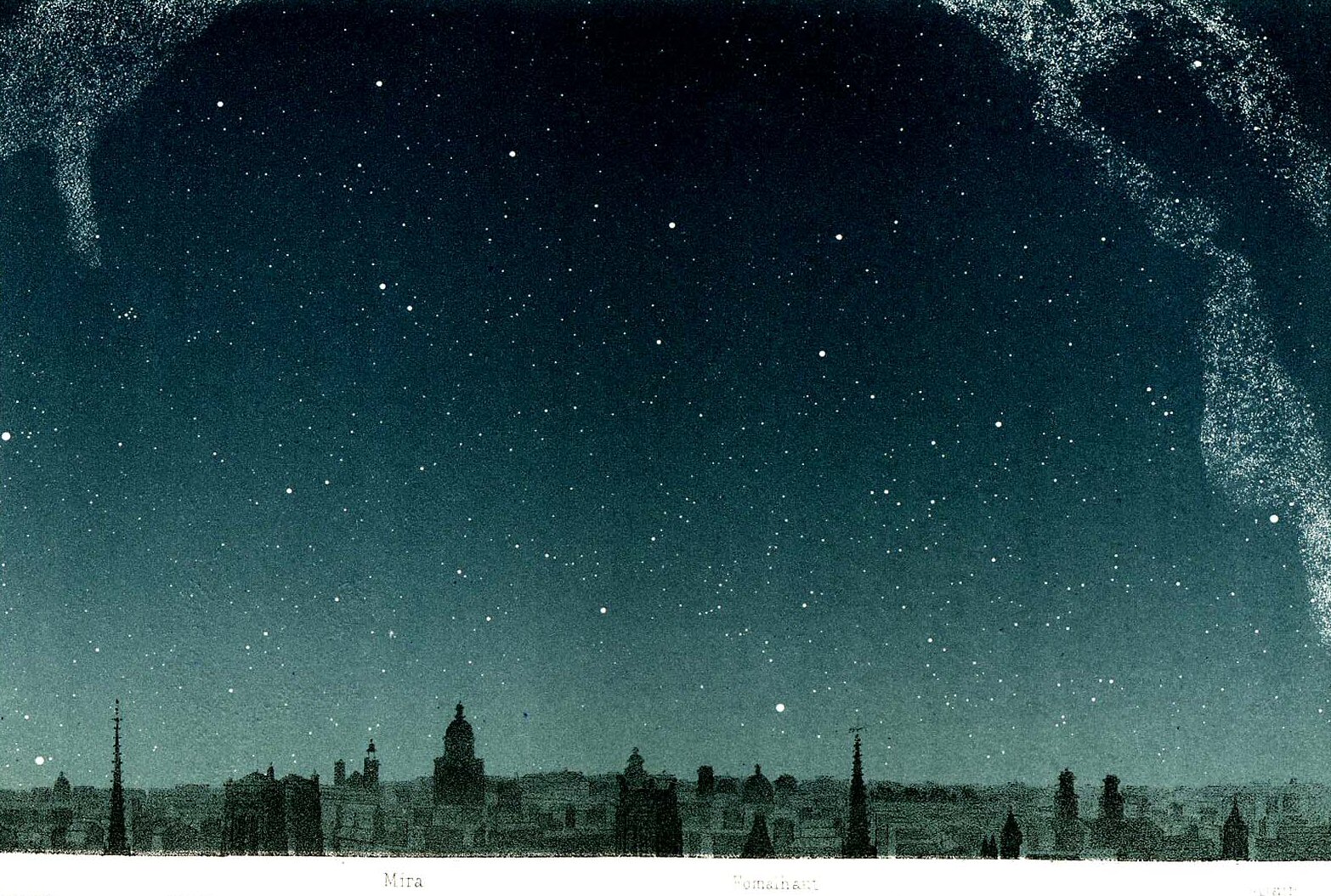

All the other letters were similar. Complaints, gnashing of teeth, rending of garments, rage, threats. Some were written in the blood of ducks, never a good sign – and I use the word “sign” significantly. I never responded to a single one of these missives. I thought I was in the clear. I did not know how grindingly slowly the Astrological Courts worked. But yesterday their judgement arrived, in the form of a peculiar light in the sky and a distant booming, as of a foghorn or perhaps a bittern. And when night fell, I cast my gaze upwards, as I always do, and the sky was empty of stars.

I still believe I did no wrong. I blame Blodgett. I shall appeal to the Astrological Courts, and hope for some shred of mercy in the sublunary world.

On Blodgett’s Jihad

Given the latest act of lethal stupidity by the homicidal barbarian community, it seemed timely to repost this piece, which first appeared exactly six years ago today.

Bad Blodgett! One Tuesday in spring, he went a-roaming among the Perspex Caves of Lamont, part of that magnificent artificial coastline immortalised in mezzotints by the mezzotintist Rex Tint. Sheltering in one of the caves from a sudden downpour, Blodgett took his sketchbook out of his satchel and passed the time making a series of cartoon drawings of historical figures. The pictures were imaginary likenesses, of course, for Blodgett was ignorant of many things, and he had no idea what Blind Jack of Knaresborough looked like. Nor was he at all sure that his double cartoon of Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray bore any resemblance to the stars of Double Indemnity. The rain showed no sign of ceasing, so Blodgett filled page after page, scribbling drawings of Marcus Aurelius, Christopher Smart, Mary Baker Eddy, Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, and the Prophet Mohammed, among others. It was this last cartoon that caused ructions which were to have so decisive an effect on Blodgett’s life.

Later that day, on his way home from the Perspex Caves of Lamont, Blodgett inadvertently left his sketchbook on the bus. A week or so later, a bus company employee was checking through the lost property and took a few moments to leaf through the book. Turning the fateful page, this employee – an adherent of the Islamic faith – was by turns outraged, humiliated, mortally offended and infuriated when he saw Blodgett’s cartoon. As is the way with such matters, he immediately arranged for copies to be distributed to mullahs and imams around the world, so that they too could share his outrage, humiliation, mortal offence and fury. Soon there were calls for Blodgett to be beheaded or otherwise put to death, and he went into hiding. Let’s take a look at the picture, so that we can understand what all the fuss was about.

(In an interesting side note, there was a similar flurryof anger from a sect devoted to the cult of Fred MacMurray, but this fizzled out after Blodgett pledged to attend a penitential screening of one of the actor’s late pieces of Disney pap.)

Meanwhile, hiding out in the Perspex Caves of Lamont, the evil cartoonist had time to think through what had happened. Blodgett was aware that the Victorian atheist Charles Bradlaugh had described the Christian Gospels as being “concocted by illiterate half-starved visionaries in some dark corner of a Graeco-Syrian slum”, and he did not think it much of a leap to conclude that the Prophet Mohammed was an equally deluded soul, although perhaps a better-organised one, with access to weaponry which enabled him to spread his message faster and more efficiently.

Around this time, Blodgett received through an intermediary an offer from the furious and offended Islamists. The sentence of death could be rescinded, they suggested, if he made a sincere conversion to their faith and promised to live out the rest of his days in submission to Allah. Blodgett considered this for about forty seconds before rejecting it. Apart from anything else, he reasoned, it was very unlikely that Mrs Blodgett would agree to spend the rest of her life cocooned in a person-sized tent and to stop going out by herself.

Shortly after this, still in hiding, Blodgett had a brainwave. Indeed, he became somewhat furious and offended himself. The conversion offer, he decided, was an example of the old cliché “If you can’t beat them, join them”. Well… he would join them, but not in the way they thought. If half-starved visionaries could propagate the Christian gospels, and Mohammed could claim to have heard the voice of God, as so many others down the centuries had insisted, with varying degrees of success, that they were in direct contact with supernatural powers, what was to stop Blodgett announcing that he, and only he, had found the true path? From this spark of inspiration was Blodgettism born.

He began to make clandestine visits to the municipal library at Blister Lane, devouring, among other works, the Qu’ran, the Bible, the collected works of L Ron Hubbard and David Icke, the Book of Mormon, sacred texts from all the major religions and many of the minor ones, even a couple of novels by Ayn Rand. After a few weeks of constant reading, Blodgett set out to define Blodgettism. He did not want it to be a synthesis of every other faith – that seemed a little too pat, a little too Blavatskyesque – and nor did he want it to be simply an amalgam of the good bits. Considering that he was still under sentence of death from a number of shouting men with beards, Blodgett wanted Blodgettism to be a faith at once as rigorous and intransigent as Islam. Thus, he cast aside with reluctance some of the more amusing things he had learned, such as underwear regulations in Mormonism, and Mr Hubbard’s intergalactic drivel, and fixed his attention on jihad. As far as jihad-as-inner-struggle was concerned, Blodgett could not give a hoot. But jihad-as-holy-war appealed to him as a way of taking on his persecutors, and thus became the most important feature of the Blodgettist religion.

In The Book Of Blodgett, published in paperback the following year, it has to be said that the founder of the new religion makes an impeccably reasonable argument in favour of his faith. Having devised a set of laws – called Blodgettia – he announces that it is the duty of everyone on earth to obey them, or be killed. Taking his cue mainly from the Qu’ran and the Old Testament, Blodgett devised an appropriately illogical and arbitrary set of regulations for human behaviour. The list of laws is too long and abstruse to reproduce here, but a couple of examples will suffice.

Blodgettia Law Number 12. Thou shalt not eat plums within ten yards of a pig or a goat or a starling. Those that disobey this law will be bundled up in sacking and thrown into a canal.

Blodgettia Law Number 49. It is forbidden to wear your hat at other than a jaunty angle. See appendix for diagrams of angles of jauntiness and non-jauntiness. Officials of the Committee For The Promotion Of Blodgettian Virtue And The Wholesale Suppression Of Blodgettian Vice And Abomination, armed with protractors and tape measures, will fan out across the land, and where they find hats worn at non-jaunty angles they shall proceed to poke malefactors with pointy sticks before putting them to an entirely justifiable death.

Of course, the Prophet Mohammed – let’s just take a look at that picture again, to remind ourselves –

As I was saying, the Prophet Mohammed was able to spread his word through a combination of historical and geographic circumstance and violence. Alas, Blodgettism never really took root, numbering perhaps only three or four devotees at its height, including Blodgett himself. But there are a few copies of The Book Of Blodgett which have not been pulped or thrown into dustbins, and they may yet inspire a new generation of fanatical adherents, who will demand, in big shouty voices, that they are right and every one else is wrong, and get very upset and angry if you disagree with them, and it will be your fault if they decide to blow you up or chop off your head. Be warned.

Urban House Numbers

“Street addressing is one of the most basic strategies employed by governmental authorities to tax, police, manage, and monitor the spatial whereabouts of individuals within a population. Despite the central importance of the street address as a political technology that sometimes met with resistance, few scholars have examined the historical practice of street addressing with respect to its broader social and political implications… We are particularly interested in showcasing recent work that links the history of urban house numbering to broader debates concerning the interrelations of space, knowledge, and power that have animated contemporary discussions in the social sciences and humanities.”

Call for papers for a special section in the journal Urban History on the history of urban house numbering, cited in Pseuds’ Corner, Private Eye, No. 1269, 20 August – 2 September 2010.

In his days as an armchair revolutionary, Blodgett became peculiarly exercised about urban house numbering. He lived at the time at 6 Rolf Harris Mew. Most Mews are plural, but this one wasn’t. There were nine bijou little dwellings in the Mew, and with what Blodgett identified as a typically hegemonic capitalist patriarchal linear system of oppression they were numbered, consecutively, from one to nine.

Blodgett had to subject this system to a rigorous poststructuralist interrogation before he was in a position to subvert it, and this he did, strolling up and down the Mew making notes, accompanied by impossibly complicated diagrams, in his jotting pad. Across the way, crippled mendicants, brought to such a state of destitution that they were lower even than the lowest of the lumpenproletariat, wallowed in their own filth and wailed for crumbs. Blodgett occasionally went over to consult with these wretches, garnering their views on his important research.

His first step in defiance of an unconscionable tyranny was to upend his door number so that it looked like a 9 rather than a 6. For this blow against the system he was shouted at by the postie and beaten insensible with a club by the occupant of number 9. Blodgett had, of course, expected violence as the response to his supremely transgressive act. But, he asked himself as he lay bandaged in a clinic, was it transgressive enough?

When he was well enough to return home, he stole out one night and, using a screwdriver, removed the door number from each house in the Mew. He made a pyre of them and set them ablaze, using an oil-soaked rag liberated from one of the mendicants. By the light of the fire, he took a paint pot and daubed upon each door a slogan of resistance. For this, he was again shouted at by the postie, and again beaten insensible by the occupant of number 9, a person labouring under false consciousness who was joined, on this occasion, by three or four of the neighbours.

This time, upon his discharge from the clinic, Blodgett discovered that all trace of his daubings had been erased, and brand new metal numbers affixed to the doors, except his own, which now had nailed to it, in a clear plastic bag as protection from the incessant rainfall, a notice from the civic authorities. Blodgett sat on the stoep to read it. In essence, it told him that he was a fathead and an idiot.

Poor Blodgett! For a while it looked as if he might be homeless, and have to join the wretched untermenschen across the way. But then he had one of his magnificent Blodgettian brainwaves. He scampered off to the civic authorities’ oppressive brutalist headquarters and explained to an official that he was an artist. This declaration did the trick. He was welcomed back to Rolf Harris Mew as a returning prodigal, even by the bourgeois scum at number 9, and resumed his activities, talking Twaddle to Power.

Gethsemane Picnic Time

One vile broiling August afternoon, Blodgett sold his birthright for a mess of pottage. Ever the wheeler-dealer, he then immediately sold the mess of pottage to a wealthy fool for thirty pieces of silver. Blodgett licked his lips and punched the air with his hairy fist. “At last!” he thought, “I have sufficient funds to organise a picnic in the Garden of Gethsemane!”

Blodgett travelled thither by hot air balloon. He was accompanied by his next door neighbours at the time, a peevish couple who rarely spoke directly to each other but babbled incessantly at Blodgett, who eventually stuffed cotton wool into his ears. For all his faults, Blodgett was a singularly honourable fellow, and he felt a sense of obligation to Mr and Mrs Fagash for a favour done to him long ago, though he could no longer remember what it was. Thus he was able to kill two birds with one stone, as they say, by fulfilling a personal picnicking ambition at the same time as repaying a moral debt by providing a treat for an elderly impoverished couple.

The picnic hamper was an exact replica, scaled down, of the balloon basket. The wicker of which both were woven had even come from the same wicker factory. Blodgett had stocked the hamper before the voyage with much provender from his favourite picnic supplies shop. Without bothering to quiz Mr and Mrs Fagash on any dietary preferences they may harbour, he had spent some of his pieces of silver on sausages and lemonade and sandwich paste and pork scratchings and flan and jam and buns and sultanas and mashed potatoes and raw liver and meringue and plums and milk. The threesome took it in turns to keep flies away by waving fans, of the same wicker as the hamper and the balloon basket. Flies, they knew, would find a way to wriggle through the tiniest gaps in the wickerwork.

If it had been vile and broiling back at home, it was even more vile and more broiling in the Garden of Gethsemane when their balloon basket thumped to earth. Blodgett himself broke out in a sweat so deep it was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground, like Christ. Hearing a series of bangs from inside the hamper, he realised the sausages were exploding. Mrs Fagash, who was a devout Catholic, suggested they seek shelter from the sun in the misnamed Grotto of the Agony, and as they staggered towards it, she explained the misnomer, dating back to the removal of a stone in the fourteenth century. Blodgett found it hard to follow what she was saying, and resolved to consult a reference work when he returned home after the picnic. He was beginning to wonder how sinful it would be to abandon Mr and Mrs Fagash in the grotto and make the trip back alone.

In all the years he had dreamed of this picnic, Blodgett never envisaged that he would find himself sitting in a dark cave eating raw liver in the company of a pair of scowling geriatrics. Even the lemonade had gone flat, due to a bottling mishap. As he chewed and glugged and swatted away flies, he reflected that perhaps he would have been better not to sell his mess of pottage, which even now the wealthy fool would be lapping up in the cool luxury of a shaded arbour. And he further reflected that it might have been better never to have sold his birthright for the mess of pottage in the first place. For what had he gained?, what had he gained?

It was this thought, as gloomy as the gloom of the grotto, that was bloating in Blodgett’s brain when, inside the hamper, the last unexploded sausage exploded with a mighty bang. Birds scattered from the branches of the olive trees outside.

“Forgive me, Mr and Mrs Fagash, for I know not what I do,” blurted Blodgett. He stood up, flicked crumbs from his person, and sprinted out of the Grotto of the Agony across the garden to the hot air balloon. He clambered into the basket and set the burners roaring, and very soon he was aloft, and he sailed away into the blue.

Source : Picnics Of Disillusionment by Dobson (out of print)

Blodgett And His Inner Concrete Lining

Like William Taylor Marrs, Blodgett had to weigh in the balance being dead with chills or having an inner concrete lining. He was, at the time, shivering in an Antarctic cabin, having been lured there, and then abandoned, by the criminal lunatic Babinsky. Though not of a neurasthenic bent himself, Blodgett was immensely well-read in the literature of neurasthenia, as he was in the broader field of peplack. We can ascribe this unlikely erudition to the influence on the young Blodgett of his schoolteacher Margbort Stuke, for whom pep was king, and queen, prince and princeling, lord, baron and marquise. Contracted by the school to teach alg ‘n’ trig, he was ahead of his time – perhaps regrettably – in that his lessons were more concerned with self-esteem and diversity. (Incidentally, he went on to teach a college course in serial killer studies, in which the career of Babinsky loomed large.)

So as he sat quaking in his cabin with icicles forming on his nose, Blodgett recalled the choice made by Marrs in Confessions Of A Neurasthenic (1908) and resolved to cultivate an inner concrete lining. It was for this reason that he mustered a pack of huskies, harnessed them to a sledge, and mooshed them north, until he reached the sea. From there, he stowed away aboard a steamer, a sort of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket on a reverse journey, fetching up eventually upon a beach suitable for his purpose.

Blodgett built himself a shelter using driftwood and fronds, and spent months living on the beach, daily ingesting a diet of sand, crustacea, fruit-pips, oysters, and seashells. Gradually his limbs began to stiffen, but he was at no risk of chills, for even at night it was a hot beach, as beaches go.

Eventually the concrete encrustment within him rendered Blodgett almost wholly immobile. Before complete rigidity set in, he made a flag out of cut and dyed fronds, fixed it to a pole, and awaited rescue.

Carried aboard the HMS Corrugated Cardboard by stretcher, one morning in September, Blodgett was deposited in a lifeboat and covered with a tarpaulin. Twice a day a deckhand would appear, fold back the tarp, shove a funnel into Blodgett’s mouth, and pour into it an anticoagulant soft drink, sweet and syrupy, with just a hint of steak and kidney pie. By the time the ship docked at Tantarabim, Blodgett was able to walk ashore unaided, though his gait was the subject of chuckles. He went immediately to an experimental medical facility where his inner concrete lining, now somewhat softened, was extracted in one piece, drawn out through his left ear with pliers and tweezers. Exposed to the gusty Tantarabim air, it soon hardened again, and Blodgett made a living for a few years exhibiting it, standing alongside him, under the show business moniker Blodgett And His Almost Life-Size Concrete Effigy. He would play sprightly tunes upon a xylophone while his concrete counterpart stood as if listening with rapt attention.

That same gusty Tantarabim air eventually brought Blodgett down with chills, and though he did not die from them, he returned to the medical facility to see if it was possible to have his inner concrete lining reinserted.

“That will not be possible,” said the medical facility head honcho, who was none other than Babinsky in heavy disguise. He watched the disappointed Blodgett traipse away down the path, snuffling, hand in hand with the concrete effigy, and his lunatic criminal brain plotted a further enormity.

Blodgett’s Mucky Proclivities

Until now, Blodgett’s mucky proclivities have been passed over in silence by those who have written about him, myself included. They were so very mucky, as proclivities go, that to contemplate them in any detail would be to shatter the brain. Lord above, they were mucky! We must, I think, agree with Mr Tuppin, who said “of all the mucky proclivities it has been my displeasure to examine on a professional basis, those of Blodgett were without doubt the muckiest”. Of course, there is muck and muck, and some muck is filthier, much, much filthier, than other muck.

In times past, there was no way of measuring the muckiness of a person’s proclivities, and it is likely that there were proto-Blodgetts the muckiness of whose proclivities surpassed perhaps even his. We will never know. But thanks to Mr Tuppin, we are now in a position to be quite precise about the extent of the filthiness, for that costive Papist has unveiled his Patent Muck-Measuring Proclivity Gauge. It is a simple enough machine, though not to look at. Constructed of dubbin and wires and bakelite and marzipan and rotating boosters and pig iron and cloth of gold and sticks and prongs and tin and titanium and horse-wedges and cornflakes and the pips of clementines and magnetic resonating galvanised sheet metal pipes and hods and unguent and terrific flapping drapes and bleached bones from a badger and cut zinc and cement and furry funnels and cadmium and lace and snippety cloggings and dust and mud and plasmatic plasma plasm and toothpaste tubes and reconstituted guttering and elk antlers and shoddy and beef dripping and grease and the tongues of wrens coated in conductive fluid and misshapen nozzles and tar and more tar and febrifuge and other tar and seawater and duckpond water and boiling lint and the twigs of a sycamore and mustard and pegs and wool and cardboard and string and tar, tar again, and bales of rotting straw and chickenwire and nails and bunting and calcified chemical compounds and Red Hudibras and oil and cheviots and glitter and vast stained glass screens and pins and tatterdemalion webbing from Vietnam and goat horns and satin and base brickish blocky clumps of tough rubber thwarts and air bubbles and tar trapped in air bubbles and hazard lights and the blood of the lamb and jet knicknacks and petroleum jelly and baize and gauze and St John’s wort and basalt and lime and jars crammed, crammed with flakes of iron, and lead and catgut from tennis racquets and pus from buboes and scrapings from shelving units and isinglass and hair from the hanged and talc and lobster pots and dunny paint and fluorescent lanterns and paste and cracked planks and vellum and grit and Strontium 90 and cartridges and toad sweat and phosphorus and adamantine and a weird sort of non-adhesive glue and great clanking chains and gorgeous perfumes and rags and plugs and sturdy tent canvas and palings and warped fork tines and batik shawls and clingfilm and batteries and giraffe hide and litmus paper and big bolts of lead and wreckage from the Lusitania and calibrated siphons and sponge saturated with egg white and bristly pointy bittybobs and breadcrumbs and cushions and slush and wax and throbbing electric motors and vaseline, Mr Tuppin’s engine has completely transformed the business of denouncing people for their mucky proclivities, Blodgett included.

Indeed, no sooner had Mr Tuppin pushed the starter knob on his terrific machine to give it a test run than Blodgett hove into view to see what all the palaver was about, and became the very first wretch to have the full extent of his mucky proclivities properly and scientifically measured. Obviously, being Blodgett, he protested, and even had the gall to question the accuracy of Mr Tuppin’s exquisite device. But the Blodgett brow was damp with beads of sweat, and he shifted uneasily in his loafers, loafers which, I might add, were themselves covered in filth, as if he had been wallowing in the sewers, which, in all likelihood, he had been, so mucky a pup is he. Afterwards, when the Patent Muck-Measuring Proclivity Gauge spat out its results in a handy poster-sized format so they could be photocopied many times over and posted upon noticeboards throughout the faubourg, and in other faubourgs where Blodgett might go scuttling about in pursuit of his proclivities, Mr Tuppin received many pats on the back, and three cheers were shouted for him, and hats were thrown in the air to celebrate the successful launch of so useful an engine.

Blodgett himself crept away, as well he might, and he headed into the deep dense dark woods, where he found a hole, and covered himself in soil, and waited for nightfall, when owls would awaken, and hoot.

Blodgett, Killer Robot

Blodgett, of course, was often mistaken for a killer robot, whenever he went rampaging around remote rural airfields and landing strips dressed in an outfit of tin foil and sheet metal with plastic, bakelite, and glass adornments. Why, might one ask, did he make such a spectacle of himself, repeatedly?

Luckily, we have evidence from Blodgett himself. He was interviewed on the television chat show Let’s Talk To People Who Rampage Around Remote Rural Airfields And Landing Strips!, which was screened on the Swivel-eyed Nutcase TV Channel for several months in the early 1970s. I have scoured YouTube for a clip without success, but a transcript exists, which I got hold of through bribery, subterfuge, and threats of violence. Alas, it is incomplete, but a fragment is better than nothing.

Cheesy Host : Our next guest will probably surprise you, because it’s a killer robot! [Chortles.] Not really! It’s just Blodgett, in an outfit that makes him look like a killer robot! Give him a big hand!

[Tumultuous applause.]

Cheesy Host : Welcome to the show, Blodgett.

Blodgett : Yava Hoosita!

Cheesy Host : Ho ho ho! Indeed! I think what our lovely audience want to know is why you rampage around remote rural airfields and landing strips dressed like that.

[Tumultuous hoots of agreement from the audience.]

Blodgett : Well, Sacheverell, as you know, we are under serious threat from Communists. Stalin may be dead these twenty years, but the Soviet beast has never been in such rude health. We could be overrun by the Red Hordes tomorrow, unless we take every precaution possible.

[Applause both tumultuous and thunderous, save from a beardy cardigan-wearing Open University lecturer.]

Cheesy Host : We all agree with that, Blodgett! But how does your rampaging around remote rural airfields and landing strips dressed as a killer robot help the fight against international Communism?

Blodgett : I have a one-word answer to that, Sacheverell…

Annoyingly, the transcript ends there.

Instances Of Inanity In Blodgett

Yesterday I alluded to three particular Blodgettian inanities. There are, of course, many, many more, so many they are numberless. But it is worth looking in more detail at the trio I mentioned, if only to get the measure of the man.

His tin shadow. The tale is told that Blodgett awoke one day in a state of terror. Whether he had had a night of awful dreams brought on by a bedtime snack of processed goat’s cheese triangles and gooseberry paste, or whether he was just in a flap, we do not know. What we do know is that when he flung open his curtains to greet the day, Blodgett found the sky to be hazy and overcast, and the sunlight so weak that it cast no shadows. In his tumultuous mental state, Blodgett took this as evidence that he was becoming, or indeed had already become, insubstantial.

A sensible person would have tested this misperception by, for example, the Dr Johnson trick of kicking a stone, but there were no stones on the floor of Blodgett’s hotel room, not even a pebble. Doubtless there are other experiments Blodgett could have tried, such as bashing his body against the walls, or plunging off the balcony. But the mania seems to have had him in its grip. Looking at himself in the mirror was no help, as Blodgett always had a grey and ghostly pallor. It was one of his defining features. As a tot, he was always cast as a ghastly wraith in the school play, even when such a character was not actually required. Peering at himself now, in the milky light of his Tyrolean hotel room, Blodgett fancied that he was becoming transparent.

Hastily dressing in what fashionistas would deride as “tatterdemalion casual”, Blodgett crashed out of the hotel into the abnormally bustling streets. All these Tyrolean folk going to and fro, bent on their mysterious Tyrolean business, seemed solid enough. Blodgett, on the other hand, felt himself wafting, as if he were but a wisp that would be blown away by the first gust. The haze was oppressive however, and there was no hint of wind. Blodgett found a cafeteria attached to a secondhand snowplough dealership where he took breakfast. As he dunked iced dough fingers into a thin broth, he kept checking to see if his shadow had appeared, but there was no change in the light. It does not seem to have occurred to him that nothing else was casting a shadow in that town, on that morning. He was, as usual, a monster of egocentricity.

The reports tell us that after breakfast, Blodgett visited the town’s one and only metallurgical institute, where he badgered the janitor to let him in. It appears that he then armed himself with some hammers and cutting blades, found a supply of tin, hammered a quantity of tin into a flat sheet, and cut an outline of his body with the blades. He was seen carrying his tin effigy through the streets, heading towards a Tyrolean glue and adhesive supplier. The next witness statements indicate that Blodgett had glued the feet of his tin self to his heels, so that as he strode through the streets and lanes and expansive boulevards of the town, he dragged the tin Blodgett behind him, like a shadow. It is said that he was much becalmed, and no longer jangling with terror.

The Swiss dramaturge Rolf Turge wrote a squib based on Blodgett and his tin shadow, in which the lead character goes berserk when the haze disperses and sunlight batters down upon the town, casting shadows so strong they are as black as pitch. In real life, Blodgett was oblivious to the sun, and he dragged his tin shadow with him for months and months, until the glue dissolved when he stepped into a chemical puddle outside a post office in Pepinstow.

His dockside groans. Can one reasonably include Blodgett’s dockside groans in a list of his inanities? After all, which of us has not groaned when trudging around the docks? There is surely something about all that clanking and shouting, the winches and bales, the crates and chains, the chugging and hooting, the stink of oil and fish and brine, that elicits a groan from the sunniest of dispositions, and not just a single groan but a whole series of them. Why, then, charge Blodgett with inanity, when his dockside groans were of a piece with yours or mine? Do we succumb to inanity too? Well, no, of course we don’t. We are level-headed, sensible persons. And Blodgett, of course, was not. He lived in a fool’s paradise. So when we consider him plonking himself down on an iron bench at Pepinstow docks, and groaning, we think to ourselves, “there is a man flailing helplessly in the extremes of inanity”. He may no longer have a tin shadow glued to his heels, for the glue dissolved just a couple of hours ago in a chemical puddle outside the post office, but he is by no means freed from his embonkersment. Look, a gull has perched on the bench next to him. Now, soberly, taking your time, judge them both, the man and the bird, and choose which one you would trust to best perform a simple task such as savagely ripping and rending a sturdy cardboard box to shreds. Your answer will not, I think, be the man with the ghostly pallor who sits there groaning, groaning at the dockside.

His futile picking at unbuttons. Blodgett devoted much of his time, one autumn, to a study of the unbutton. At first, he went off on completely the wrong track. Adducing that the unbutton was “that which is not a button”, Blodgett mistakenly concerned himself with “that which is, where the button is not”, in other words, the buttonhole, the emptiness, the void the button will, one day, occupy, or, perhaps, once did occupy, before its thread snapped and it fell into a puddle, perhaps even the chemical puddle outside the post office in Pepinstow, where it lay alongside Blodgett’s unglued tin shadow. But of course a buttonhole is but a buttonhole, not an unbutton. Autumn was a month old before Blodgett realised his error. He had been shuttered in his Tyrolean hotel room picking futilely at buttonholes, only occasionally stepping out to wolf down breakfast and afternoon tea and dinner at a cafeteria. Then, one morning, he had an epiphany. A monologue devised years later by the Swiss dramaturge Rolf Turge gives us a flavour, albeit imagined, of the Blodgettian brainpan pirouettes of that day.

I was picking futilely at a buttonhole when a crow landed on my Tyrolean hotel room windowsill. I cast aside the buttonhole and looked at the crow, and the crow looked at me. I thought, if I were to make a puppet of the crow, out of black rags and tatters, I would use buttons for its eyes, would I not? And then I thought, perhaps the crow is thinking of making a puppet Blodgett, out of torn-up shrouds and winding-sheets. Would it, too, make my eyes out of buttons? Or, being a crow, primed by the bird-god that made it to peck out my eyes, would it need, for its puppet, not buttons, but unbuttons? That is when I realised that the unbutton is something greater, stranger, far more uncanny than a mere buttonhole. The crow flew away, bent on Tyrolean worms no doubt. But I had seen the error of my ways, and I stamped my foot repeatedly upon the buttonhole I had been picking at with such futility, and I crashed out of my hotel room into the street, the abnormally bustling street, and my eyes glowed brightly, real eyes, not shiny buttons on a puppet, and I strode with my head held proud and high, seeking afresh the true unbutton I knew, now, was there, somewhere, hidden in plain sight.

By the time autumn turned to winter, Blodgett had found an unbutton, or at least what he took to be one. Certainly it met the definition of “that which is not a button”, and Blodgett pounced upon it, there in that Tyrolean town. Yet, having found it, what did he do? It is a measure of the man’s inanity that he simply picked at it futilely, for days on end, sitting on an iron bench at the dockside, groaning, shadowless, having fled the Tyrol for Pepinstow, in the autumn of 1963, just before the Kennedy assassination, and the Beatles’ first LP.

Inanity And Its Bedfellows

I am beginning to think that stealing the titles of other people’s blog postages may be the Way Forward… forward, of course, to that bright upland where I can bask under the Aztecs’ mighty orb when my work is done. Even while the Key cranium is ticking and whirring as it ponders John Ptak’s postage header along comes Patrick Kurp at Anecdotal Evidence with “Emptiness; Uncertainty; Inanity”. Again, I advise you to read the original postage, but meanwhile I shall be pondering some prose to which it will serve as a fitting title.

The “inanity” part should give me no trouble, as virtually any anecdote about Blodgett will fit the bill. His tin shadow, his dockside groans, his futile picking at unbuttons… there is so much material. But “emptiness” and “uncertainty” may be more troublesome.

One uncertainty is to what extent I can get away with writing about prose I have not yet written. Best not to dwell upon it, for that way emptiness lies.

ADDENDUM : As Dave Lull notes in a comment, Patrick Kurp’s title is a quotation from Dr Johnson’s A Dictionary Of The English Language (1755). Though that is clear from reading the postage, I ought to have acknowledged it here.

Bungled Heists

At the last count, Blodgett is thought to have been involved in no fewer than six bungled heists. By comparing the circumstances of each heist, we may learn not only about their bunglement, but something, too, about Blodgett the man.

First heist. The plan was to steal a consignment of birdseed being delivered to a crow sanctuary. Prices in the millet market had rocketed, and a tidy sum could be expected when the “hot” birdseed was offloaded to a fence. The gang spent weeks hidden behind a hedge observing the routine. At exactly 11 o’ clock each morning, a truck arrived at a gate in the perimeter fence and, after a cursory check of paperwork, it was waved through and driven at snail’s pace to the silo, whereupon a sanctuary worker hauled the vacuum-packed bags of millet off the truck and put them on a hoist which was winched up to the top of the silo. There, on a platform, a second worker slit each bag open with a birdseed-bag-cutter and dumped the contents into the silo. The empty bags were chucked back to the ground and replaced on the back of the truck, which then drove off, through the gate. The entire operation took about fifteen minutes. Blodgett’s role was to thump the truck driver and the gatekeeper, disabling them for sufficient time to allow the gang to steal the birdseed before the truck entered the crow sanctuary. At this time, Blodgett carried quite a thump, and he practised it on life-size cardboard cut-out persons, which toppled over at the first thump. This was the key to the embunglement of the heist. Both the truck driver and the gatekeeper were great thick-set brutes, much less flimsy than Blodgett’s practice figures. When thumped, neither of them toppled over. Instead, they thumped back, the two of them, with alarming violence, until Blodgett was sprawled on the ground battered and bloodied and unconscious, at which point they summoned Detective Captain Cargpan by walkie-talkie.

Second heist. Blodgett joined a different gang for his next heist. This was a smaller-scale affair, the aim being to pinch a packet of arrowroot biscuits from a half-blind doddery octogenarian crone as she creaked along a secluded lane. Technically, it can be argued that such a venture falls outwith the strict definition of a heist, but quite frankly I am not prepared to countenance such a cavil, as it would threaten the basic integrity of my narrative thrust. The idea was that the gang would hide behind a clump of aspens, and, at the approach of the crone, Blodgett would leap out into her path and thump her. Taking advantage of her surprise, alarm, and possibly fatal injury, another member of the gang would snatch the packet of arrowroot biscuits from her pippy bag, and the gang would make off with all due speed, cackling. In this case, the bunglement consisted of failure to realise that the crone in question was Mrs Gubbins, herself a criminal mastermind, and one who could deploy her knitting needles to lethal effect. When set upon by Blodgett, she poked him in the solar plexus with a sharpened 4.25, jabbed his head with it as he crumpled to the ground, and then coolly tucked it back in her bag before calling Detective Captain Cargpan on her klaxon.

Third heist. Blodgett had rejoined his original gang, but made it clear he wished to have no part in any thumping on the next job. He was thus engaged as a look-out man. Blodgett did not pay attention, however, to a particularly riveting Dan Corbett weather forecast, and was ill-prepared when a dense and freezing and engulfing mist descended upon him as he sat in his perch overlooking the big cash-register warehouse. He was peering hopelessly into the murk when he felt the begloved hand of Detective Captain Cargpan nabbing him on the shoulder.

Fourth heist. This heist was, at least in its conception, the most ingenious. Inspired by the classic art-house film Snakes On A Plane, had it been fictionalised for the cinema it could have been called Otters In A Laundry Basket. Unfortunately, the otters escaped from the laundry basket and ran away to a riverside before they could be deployed. This was Blodgett’s fault, as he had been enrolled into the gang specifically to train and control the otters. He was in bad odour after this, and considered becoming an informer for Detective Captain Cargpan, but instead holed himself up in a chalet in Jaywick for some years, lying low.

Fifth heist. Tempted out of his Jaywick hidey-hole by the prospect of a share in the proceeds from a daring smash ‘n’ grabby-type heist, Blodgett returned to the criminal fray as part of yet another gang. A plate glass window was to be smashed, and a display of ornate cornflake packets dripping with jewels was to be snatched. The packets were the work of a bumptious and bespectacled artist of great, if unfathomable, repute. Everything went according to plan, except that the gang left Blodgett to guard the art in a lock-up under the arches of Sawdust Bridge while they tracked down their expert fence, who was hobnobbing with hedge fund managers. Peckish Blodgett opened up the packets and ate all the cornflakes, dry, without milk, thus destroying their value as art. Left with nothing but a bunch of jewels, albeit valuable ones, the gang fell foul of a pasteman in the trade, who tricked them as a pasteman will, and turned them over to Detective Captain Cargpan, who was waiting outside with his ruffians.

Sixth heist. One can gain some idea of the duration of Blodgett’s criminal career when one considers that the sixth heist took place more than fifty years after the first. By now, Blodgett was old and wheezy, and as creaky as Mrs Gubbins had been (see second heist). It was his creakiness which led to the bungling of his last heist to date. The vaults of the big important bank into which the gang broke their way with the aid of industrial slicing and cutting and burrowing equipment were, of course, heavily alarmed. Multiple sensors would pick up the tiniest sound or movement. One by one, each sensor was disabled by the gang’s sensor disablement man, using his pliers or pincers or, in one case, a soaking wet dishcloth. Things were set fair for a successful heist. But Blodgett creaked as he crept towards the cash-cage, alerting a tiny rodent, which scurried in fear towards the big important bank’s basement wainscotting, and in so doing dislodged some wiring, causing a short circuit which knocked out all the electrics. Plunged into Stygian blackness, Blodgett and the gang were helpless, and could do nothing but await the arrival of the janitor in the morning. This janitor was an old mucker of Detective Captain Cargpan, who was himself on the scene within seconds, blackjack and manacles at the ready.

According to a story in a recent issue of the Weekly Heist Intelligencer, Blodgett is a member of a gang plotting a forthcoming heist at an amusement arcade in a seaside resort. Letters have since appeared in the correspondence columns pleading with the gang to drop Blodgett from their plans. The inherent sentimentality of the criminal demimonde suggests this is unlikely to happen. It is thought Detective Captain Cargpan has already splashed out on a railway ticket to the seaside resort.

Blodgett In The Sewers

Having heard rumours that the sewers of Pointy Town were teeming with strange huge bulbous blind albino beings with tentacles and suckers, Blodgett decided he would like to capture a pair and keep them as pets. Encased from head to toe in patent sewerwear, without a guide, our hero clambered down a metal ladder into the vast subterranean network of tunnels and passageways and channels and chambers. If you have seen The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949), you will grasp the essential seweriness.

The sewers of Pointy Town were the least pointy part of the town. Indeed, for whole stretches they were completely unpointy. Blodgett found this disorientating, and soon became lost. So used was he, in these latter days, to locating himself in relation to various pointy bits above ground, that their absence made his head swim, inside its big exciting helmet, and he toppled over. He had only been down in the sewers for a couple of minutes.

Although he had gone down without a guide, Blodgett was not entirely witless, and he carried with him, strung to a loop on the hip of his sewerwear, a hooter, which he could hoot to alert any members of the Pointy Town Sewer System Rescue Patrol who might be faffing about in the vicinity. He had been told about these tireless public servants by a man in a tavern, the same tavern where he had heard the rumours about the strange huge bulbous blind albino beings with tentacles and suckers. One tavern, two rumour-mongers. Unfortunately for Blodgett, the chap who told him about the rescue patrol was a chronic fabulist with a skewed brain, and he was peddling a fiction. Even more unfortunately, the hooter which this same scamp sold to Blodgett for forty panes mimicked the mating call of the strange huge bulbous blind albino beings with tentacles and suckers. And, as misfortune piled on misfortune, there was nothing remotely fictional about them!

So Blodgett, though as yet he did not realise it, was in something of a pickle. Unable to hoist himself back on to his feet, he lay sprawled on dank stone slabs, filth gushing past inches from his face. The lantern torch attached to his helmet gave him enough light to read by, so, having hooted the hooter a few times, he lit a cigarette and took from one of his pockets a pamphlet to pass the time. It was a curious piece of work by Dobson, a sort of potted biography of Hungarian football ace Ferenc Puskas intertwined with a muddle-headed meditation upon the unpopularity of certain card games. Not surprisingly, it is now out of print.

Blodgett was so engrossed in Dobson’s description of the card game My Lady’s Bonnet, interspersed as it was with vivid passages about the 1959 European Cup Final, that he only became aware of the pair of strange huge bulbous blind albino beings with tentacles and suckers slithering towards him when he felt their fetid breath on the back of his neck.

I know this is a particularly exciting point in the narrative, and I do not wish unduly to keep readers in suspense, but I can hear objections being raised by members of the pernickety community. How, they ask, does Blodgett feel breath on the back of his neck when he is encased in sewerwear, including a big gorgeous helmet? The answer of course is that a patch of muslin, punctured with many holes, is sewn into the sewerwear precisely at the back of the neck, just below the rim of the helmet, for reasons too obvious to elucidate.

Blodgett had just lit a second cigarette. With great presence of mind, and a rapidity of action learned in the testing ground of the Hideous Unlikely Swamp Of Scroonhoonpooge, he overpowered the two squelching horrors by poking one in the sucker with his burning cigarette and thwacking the other one on the tentacles with the Dobson pamphlet. He was then able to use the support of their huge bulbous bodies to lever himself upright.

Still puzzled at the non-appearance of the rescue patrol, Blodgett used his inhuman strength to drag the two strange huge bulbous blind albino beings with tentacles and suckers behind him as he trudged through the sewers seeking an exit. For the first time he was thankful for the unpointiness of his surroundings, for it made his dragging much easier than if he had had to negotiate pointy bits. That was a problem he would have to face when he was back on the surface, but he was consoled by the thought that he had enough coinage in his pockets to pay for the hire of a cart to carry the captured beings back to his decisively moderne chalet at the edge of town.

Later, much later, in fact three days later, Blodgett finally found his way out of the Pointy Town sewers. He hired a cart and carried his prizes back to his decisively moderne chalet at the edge of town. “They proved,” he wrote, “to be quite splendid pets, although I was a little upset when they ate my Toggenburgs.”

The highly amusing story of Blodgett and his goats will, alas, have to wait for another time.

Lost Names

I am a devotee of the ludicrous yet brilliant television series Lost. This surprises some readers, not least because it is of course a blatant plagiarism of the Hooting Yard serial story Blodgett And His Pals Hanging Around On A Mysterious Island After Surviving A Plane Crash, episodes of which appeared here back in December 2005 and January 2006. But I forgive the writers and producers of the American series, because I am like as unto a saint and martyr.

One of the features of the show that has always appealed to me is the manner in which certain characters are named after great thinkers of the past. Rousseau, John Locke, Jeremy Bentham and Mikhail Bakunin all appear in the Lost scripts, and there may be others I have forgotten for the moment. Early on, I assumed the significance of these dubbings would become apparent, until at last it dawned on me that they are, though deliberately chosen, purely arbitrary. A programme such as Lost encourages fervent babble in online fora and discussion groups, where airheads expound and exchange their theories about this or that clump of minutiae, and clearly these names are planted, like the books characters are seen reading, as fodder for the nutters. I must add that despite my enthusiasm for the show, I do not waste precious hours reading or contributing to the online drivel.

The point of noting this is that it has only belatedly occurred to me what a tremendous fictional device it is. I am minded to write stories featuring protagonists called Charles Lindbergh or John Ruskin or Tallulah Bankhead or Hazel Blears, where no reference is remotely intended to their famous living, or dead, or brain-dead, counterparts. Expect passages such as the one below to turn up at the Yard soon:

“So, Ringo Starr, you continue to defy me?” hissed evil Nazi Obergruppenfuhrer Blind Jack of Knaresborough to his quailing captive. Suddenly, a rescue party led by daring trio Nova Pilbeam, Ivy Compton-Burnett, and Thomas De Quincey crashed in to the chamber. The Nazi hellhound spun on his heels, but was swiftly grappled to the floor by David Miliband.

Later, as the gung ho heroes sat in the helicopter taking them back to Blighty, they were moved to receive congratulatory radio messages from both Richard Milhous Nixon and Ayn Rand.

Wilf

Dear Frank, writes Tim Thurn, who has taken to calling himself Tim Thurn Of That Ilk, I assume in a desperate attempt to lend himself some gravitas, I was intrigued to read in your account of the Old Farmer Frack Memorial Essay Contest that the judges would include Wilf Self, Wilf Amis, and Wilfette Winterson. I have never heard of any of these people, despite being incredibly well-informed in all manner of subjects. Indeed, so huge is the amount of information stored within my brainpans that I have been compared, by idiots, to Stephen Fry, and by people with a modicum of sense to Roger Bacon (c.1219-1294), “Doctor Mirabilisâ€, the man who, it was claimed, had read everything.

Not wishing to doubt your word, I ran the names past my uncle, whose name also happens to be Wilf. He looked at me witheringly and, with barely a pause, accused you of having invented your Wilfs, and Wilfette, out of whole cloth. “These people do not exist,†were his exact words, and I believe him, for he has made a point, during his long life, of keeping tabs on all the Wilfs and Wilfettes who have ever existed. Some may think it a foolish hobby, and it probably is, but that’s my Uncle Wilf for you.

Anyway, his pronouncement set me thinking. Why, I asked myself, would Key go to the trouble of making up a couple of Wilfs and a Wilfette when he must have known that he would be exposed as a fraudster and scoundrel as soon as anyone took the trouble to check? I must admit that for quite some time I was stumped. I just sat there, chewing the end of a pencil, risking lead poisoning, beflummoxed. But soon enough it was time for Uncle Wilf’s daily outing, and I pushed him in his super whizzo wheelchair a few times around the pond, the pond next to the cement facsimile of the Old Tower of Lobenicht. You will recall that as the tower which Immanuel (not Wilf) Kant liked to look at through his window as he sat by the stove in circumstances of twilight and quiet reverie, not that he could be said properly to see it. Perhaps something of Kant’s cerebral magnificence imbued my own brain, in spite of the cement copy being a poor substitute for the real tower, for in a flash of insight I realised what it was you were up to.

My theory, which I am going to write up into an essay and have published in some obscure and unread academic journal, Wilf willing, is that you were dropping great clanging hints to your readers of the full names of some of those Hooting Yard characters whose first names we are never given. Wilf Dobson? Wilf Blodgett? Old Ma Wilfette Purgative? Old Farmer Wilf Frack himself? You need neither confirm nor deny that this is the case, Mr Key, for so sure am I of the stupendous accuracy of my flash of insight that I know, as well as I know the consistency of the drool dribbling down my Uncle Wilf’s chin, that I will be proved correct in the Harmanite court of public opinion, the only court that counts.

Yours ever, Tim Thurn Of That Ilk (and his Uncle Wilf, Of That Ilk)